In 2017, there have been several important contemporary art exhibitions in Korea under the name “Asia.” The list is as follows: Imaginary Asia (March 9–July 2) at Nam June Paik Art Center; 2017 Asia Pacific Contemporary Art: Hello, City! (June 23–October 9) at Daejeon Museum of Art; 2nd Asian Film and Video Art Forum (August 30–October 8) at Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art; Asian Diva: The Muse and the Monster (July 14–October 9) at SeMA, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art; and Asia Women Artists at Jeonbuk Museum of Art (September 1–December 3). This article aims to go over these five exhibitions related to Asia and examine the way in which our art world thinks of and displays Asia. Although our idea of Asia cannot be thoroughly comprehended by looking at a few exhibitions, we may, at least, be able to get a general picture of the common trends of how we approach today’s Asia.

An installation view of Asia Women Artists, 2017. Photo credit: Seo Ji-yeon

An installation view of Asia Women Artists, 2017. Photo credit: Seo Ji-yeon Spectrum of Asia

In many cases when we hear Asia, we tend to think of a few familiar countries. However, five exhibits that will be examined in this article commonly emphasize the diversity within Asia. What stands out in these exhibits is that they present works of artists from diverse national backgrounds, which go beyond the familiar names of Korea, China and Japan. Imaginary Asia presented works by artists from thirteen different countries; 2017 Asia Pacific Contemporary Art: Hello, City! eight; 2nd Asian Film and Video Art Forum approximately twelve; Asian Diva: The Muse and the Monster roughly five; and Asia Women Artists ten. Among the countries represented are Myanmar, Lebanon, and Cambodia, which are countries relatively unfamiliar to the Korean audience in terms of contemporary art.

In addition, each exhibition reminds us that the nations belonging to Asia have different cultures, histories, daily lives, and politico-economic conditions. For instance, the primary objective of Imaginary Asia was to show the diverse historical experiences of different Asian countries. The 2nd Asian Film and Video Art Forum underscores that every Asian country has a different history as well as social and political environment, and Asia Women Artists also emphasizes that women in Asia are placed under different situations depending on their conditions and nationality.

It is an unquestionable fact that there are many different countries in Asia; and that, therefore, each country has a different history, culture, and experience. What we call Asia is the largest continent on earth with the biggest population, which includes numerous different countries such as Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia, Brunei, Philippines, Thailand, Turkey, and, sometimes, even Russia and Israel. History and culture as well as climate and language are various. The exhibitions on Asia that opened this year effectively reminded us of this fact, which often gets obliterated.

Tanya Schultz, Where there is a flower (There must be a butterfly, so that flower shined more brightly), 2017, polystyrene, glitter, plastic flowers, lope. paper, tape, cardboard, wire, craft materials, Dimensions variable ⓒ Daejeon Museum of Art.

Tanya Schultz, Where there is a flower (There must be a butterfly, so that flower shined more brightly), 2017, polystyrene, glitter, plastic flowers, lope. paper, tape, cardboard, wire, craft materials, Dimensions variable ⓒ Daejeon Museum of Art. Exposing the diversity inherent in Asia is something that the scholars of modern and contemporary Asian art have been doing since the late twentieth century. Apinan Poshyananda urged early on that the diversity of art created in the Asia Pacific region be revealed.1) Then, in 1996, T.K. Sabapathy proposed that Asia should be viewed as a mosaic.2) In 1997, Hou Hanru and Hans-Ulrich Obrist tried to show the particularity of each city when they curated the exhibition Cities on the Move.3) In 2003, Wang Hui pointed out that it was time that we focused on cultural heterology of Asia.4)

1) Apinan Poshyananda, “The Future: Post-Cold War, Postmodernism, Postmarginalia (Playing with Slippery Lubricants),”in Tradition and Change: Contemporary Art of Asia and the Pacific, ed. Caroline Turner, St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1993.

2) T. K. Sabapathy, “Developing Regionalist Perspectives in Southeast Asian Art Historiography,” in The Second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, ed. Caroline Turner and Rhana Devenport, Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1996.

3) Hou Hanru and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “Cities on the Move,” Cities on the Move, Ostfildern-Ruit: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1997.

4) Wang Hui, “Imagining Asia: A Genealogical Analysis,” International Symposium 2005: “Cubism in Asia: Unbounded Dialogues” Report, ed. Furuichi Ysuko, Tokyo: Japan Foundation, 2006.

The scholars’ and exhibition organizers’ recent change of attitude to underscore the diversity in Asia is something that is distinct from what existed before. In terms of discussion of modern and contemporary Asian art, the point of comparison has often been Europe and America, or what was called the West. When the previous generation of scholars discussed modern and contemporary Asian art as the works that were created under the particular history and culture of Asia, they asserted that contemporary Asian art was different from the contemporary Western art. What lay behind this argument was the intent to overturn the criticism that Asian art was oftentimes formally inarticulate and outdated—in other words, European and American art was the creative original and that Asian art was a poor imitation. They chose to compare the West and the East and emphasize the originality of the latter. After a long and ardent discussion that went on until the early 2000s, which reached a rough conclusion that modern and contemporary Asian art is a “productive mistranslation” of the European original, the center of discussion seems to have moved away from comparing the West and the East and now gravitated towards stressing the diversity within Asia.

To point out a particularly exciting aspect in this turn of events, it seems that revealing diversity within Asia demonstrates the effort to include those who have often been neglected and alienated by mainstream art. For example, Asian Diva: The Muse and the Monster paid attention to “the subculture that was stigmatized as decadent by violence and oppression and the voices of the women and the other that were alienated from patriarchal military culture.” In a similar context, Asia Women Artists focused on the works of female Asian artists, who were doubly discriminated against by their race and gender. These attempts to show a more dynamic Asia by including the parts that have been neglected thus far have enriched the discourses pertaining to Asia, which could have grown monotonous, and have worked as an effective measure to maximize the “diversity within Asia” maintained by these exhibitions.

Left) Yun Suknam, White RoomⅢ, 2017, Mixed media, Dimensions variable, Photo credit: Seo Ji-yeon

Left) Yun Suknam, White RoomⅢ, 2017, Mixed media, Dimensions variable, Photo credit: Seo Ji-yeon Right) Sung Neungkyung, An upside-down Map of world, 1974 ⓒ Seoul Museum of Art

Concept of “Asia”

However, if Asia is so diverse in its culture, history, and memories as is asserted by these exhibitions, is it even possible to bind everything under the category of “Asia”? Is the concept of “Asia” valid as to encompass all these diversities?

The aforementioned scholars argue that because Asia has such a wide spectrum, the Asian identity as a homogeneous entity does not exist. Melissa Chiu and Benjamin Genocchio affirmed in their introduction to the Contemporary Art in Asia, which is a collection of essays on Asia, “It is well accepted by arts cholars today that ‘Asia’ is more of an elusive, slippery concept than a homogeneous physical, social, or cultural entity.”

Five exhibitions under discussion in this article share the common perspective of revealing the diversity of Asia, but they show differing views on the concept of Asia itself. The exhibition at the Nam June Paik Art Center put up the title Imaginary Asia, which is an acknowledgment that while the concept of Asia is still valid, its substance is something to be called into question. By designing the exhibition in two categories, the exhibition presented a compromise, which combined the two conflicting positions. The first category mainly consists of pieces by East Asian artists, expressing the historical identities of their own countries, and the second category featured video art from the countries that straddle the border between Asia and West.

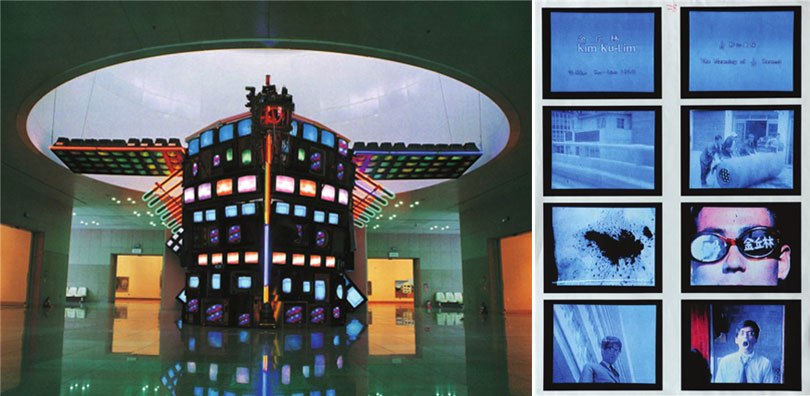

Left) Nam Jun Paik, Fractal Turtleship, 1993, TV, piano, taxidermy turtle, Dimensions variable ⓒ Daejeon Museum of Art

Left) Nam Jun Paik, Fractal Turtleship, 1993, TV, piano, taxidermy turtle, Dimensions variable ⓒ Daejeon Museum of Art Right) Kim Ku-lim, The Meaning of 1/24 Second, 1969 16mm film colour+BW, 9mins 12Sec, Photo credit: Seoul Museum of Art

On the other hand, Asian Diva: The Muse and the Monster maintained a position closer to that of accepting the concept of Asia in that it assumed the common influence of Cold War and Vietnam War on Asian countries. It defined the concept of Asia targeted in the exhibition quite clearly in its objective, as it mentioned “the domain of post-colonial culture including Korea and Southeast Asian countries.” The pieces presented in the exhibition also corresponded to this concept. The 2nd Asian Film and Video Art Forum stated that since the Asian countries have undeniable common denominators, the organizers intend to remind the spectators that Asia is not a fictional concept. However, the sense of identity shared by the Asian countries was not made clear through the video works shown in the exhibition. It seems that if the sense of identity is invisible as it is stated in the exhibition, some effort should have been put in to visualize the sense of identity or to explain why it is invisible.

Asia Women Artists and 2017 Asia Pacific Contemporary Art: Hello, City! accepted the concept of Asia as an entity, but did not show much insight into the concept itself. The 2017 Asia Pacific Contemporary Art: Hello, City! exhibition included a large number of artists who work in Australia or places in the Midwest US, like Ohio, and even those who were born in Asia, but educated and work in the UK or the US. Although it could have been a great opportunity to discuss the category of Asia and its uncertainty, the fact that there was no discussion on that is regrettable. Actual content of Asia Women Artists at Jeonbuk Museum of Art seems to reveal that its focus lies more on “women” rather than “Asia.” Nevertheless, I could not help thinking that insofar as “Asia” was chosen to be included in the title, the exhibition should have at least tried to explain what it is that set the Asian women artists apart from African or European artists, or if there is no difference, why it is that they are no different.

Is it appropriate for us to keep using the term “Asia,” which originated from the name of a figure in Greek mythology? Is it possible to find “Asian-ness” even today when the geographical boundaries seem to be gradually disappearing? The answer to these questions may differ, or not even exist. However, if there were an exhibition held under the name of Asia, it would have been more inspiring to organize a public forum where these questions could be discussed and addressed more rigorously.

An installation view of Imaginary Asia, 2017 ⓒ Nam Jun Paik Art Center

An installation view of Imaginary Asia, 2017 ⓒ Nam Jun Paik Art Center Power of Asia

The last question I would like to raise is why it is that we talk about Asia. What is the reason there are so many exhibitions on Asia? What are their ultimate goals?

The shared objective of the five exhibitions telling the diverse stories of Asia is, in a broad sense, one way of emphasizing the autonomy and independence of Asia. It expresses the will to tell a story from each one’s perspective and listen to each story, instead of seeing everything from a single point of view forced by one powerful entity. Imaginary Asia shows “an open–ended, far from complete or comprehensive, archiving of distantly connected layers of histories” different from History written by the victors. Asian Diva: The Muse and the Monster discloses the manner in which the “political and cultural field represented by the Cold War ideology was localized.” Ultimately, the objective of these two exhibitions is to tell the stories of Asia from the Asian perspective. The 2017 Asia Pacific Contemporary Art: Hello, City! exhibition, which promotes the interchange between Asia Pacific countries, and Asia Women Artists, which connects Asian women, share the objective of securing Asian power, or, more precisely, the power to counteract Europe and America through Asian solidarity.

Left) Gina Kim, Bloodless, 2017, VR color 12 min. Photo credit: National Museum of modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)

Left) Gina Kim, Bloodless, 2017, VR color 12 min. Photo credit: National Museum of modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)Right) Nguyen Thi Trinh, Letters from Panduranga, 2015, 35 min. Photo credit: National Museum of modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)

As it is well known, center of art world prior to World War II had been Western Europe, pivoting around France, and after World War II, it moved to the US. Also, as it has been mentioned and discussed time and again, the agent of power in the contemporary art is primarily the white Western male. In order to break the racial imbalance of power existing in art word, academia has rejected the dichotomy of East and West, and proposed ways to create multiple centers instead of one. Although there are curators, artists, and scholars of diverse national backgrounds emerging and actively working in the “mainstream art world,” it is hard to deny that the art world is still moved by a few central countries in America and Western Europe. Academically, it is often the case that people follow the methodology of American or European scholars, and while the Asian artists, curators, and scholars may be accepted or selected into the mainstream art world, the number is not substantial enough to dilute the main components of mainstream art. The source of capital that has significant impact on the art world is still, in many cases, America and Europe. Under the circumstance, to hold exhibitions organized in solidarity with other Asian countries, and to subjectively tell individual stories of different people belonging to Asia through those exhibitions all seem to be part of ongoing efforts to resolve the power disparity.

Asia is faced with the dilemma of being homogeneously unified as one entity even though it has a much wider spectrum. Asian power is needed now more than ever. This may not be sufficient, but these are the two things that I can roughly sum up about the Asia that we view today from a number of contemporary art exhibitions that are held in 2017 Korea.

※ This article was originally published in Public Art magazine (November 2017) and reprinted under authority of a MOU between KAMS and Public Art.

Jung Ha-yoon / Researcher

Writer Jung Ha-yoon graduated from Ewha Womans University with a bachelor’s degree in Western painting, where she also earned a master’s degree in art history with a thesis on Yoo Young-guk’s works. She then received PhD from the University of California, San Diego, with a dissertation on 1980s Chinese abstract art. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Ewha Womans University, studying and teaching contemporary art of Korea and China.