Features / Focus

Preview of 2018 Biennales:Conversation(3)

Gwangju Biennale Curators

Clara Kim / Yeon Shim Chung

posted 14 Aug 2018

Gwanju Biennale 2018 Poster ©Gwanju Biennale

The first biennale’s theme was ‘Beyond the Borders.’ This year marks the 23rd anniversary of its start and the theme is ‘Imagined Borders.’ Benedict Anderson’s book 『Imagined Communities』 is a renowned work in the humanities, translated into over 15 different languages. The theme will be varied by each of curators, and it will come up with in relation to the title of this book, 『Imagined Communities』, and the spirit of the Gwangju Biennale(abbreviated as Gwangju).

Blurring tangible and intangible borders

Now, the world is in a precarious state today since the political situation or the refugee issue and situation is—as always—quite unstable. In the past, the Gwangju has designed exhibitions that reflected the contemporary. It will amplify the level of diverse voices in the cultural communities and the current growing move beyond division and hierarchy structures set up by Modernity.

Multiple curators system

As for the alternative take to reflect the modernity paradigm, for this year, The 11 curators undertook each exhibitions on its own track in the context of the main theme. It is for the first time that multiple curators are taking care of this year’s biennale. This attempt is quite new in Korea since the usual way was to have one art director in charge of the theme with 3 to 4 curators to assist. What kind of drawbacks may the new system have, and what potential may be derived from the new system in the biennale’s position? This method has been introduced to not only Gwangju, but the current Biennales as well such as Seoul, San Paulo. However, this time in Gawngju, the trial is more separate but totally summed in a picture. The way remains multiple voices and perspectives then putting it on each own place in puzzling; the question we’re tackling now in world.

Engages with the Public

With very ensure thing that all practices will get along with audiences, inclusively local community. Reminding the first time of inauguration in this Biennale, it is at disposal to follow Gwangju Spirit; for all and by all. At that time, a good number of people lined up to watch the 1st biennale. This could have resulted from the lack of international arts at the time or a national interest focused upon the ‘first’ of something, but it is sure that more and more people are finding the biennale exhibitions to be difficult. Therefore, back the time to begin, Gwangju which is crucial to both let the general public understand the exhibition with advocating important discourses of contemporary art at the same time.

Biennale and Museology

The more role and question this Biennale has to manage, the more criticism grow as behind some advocating to the biennale system in general. Though this criticism is understandable in that a huge capital is involved and biennales are rampantly spreading worldwide.

Again now, it carries the other issue in comparison to an art institution, what may be the difference or characteristic when it comes to executing an exhibition in a museum or a biennale? Recently, Claire Bishop criticized the existing museology or exhibitions through her 『Radical Museology』.

Heavily shouldering loads of issues, 2018 Gwangju is about to answer the questions on the faultlines, now. The faultlines, where is in the middle of nowhere, casts the conditions we are facing; phantom borders. And aslo it gives a room to find how to survive; assembly, sustainability and shift. Utopia would walk side by us wearing a face of distopia. This multiple exhiibions would put a piece of puzzle games in this blurring modernity picture which doens't exist substantially but having been stayed in an imagination; imagined borders.

Conversations; Clara Kim & Yeon Shim Chung

Tuning into the Contemporary and Putting a piece of Modernity Puzzle Game on faultlines

|

Clara Kim / United States, Curator at Tate Modern, 2018 Gwangju Biennale Curator Kim arrives at Tate Modern after her role as senior curator at the Walker Art Center, where she organized a midcareer survey of Abraham Cruzvillegas; prior to the Walker, Kim spent eight years at REDCAT in Los Angeles, where she was gallery director and curator from 2008–2011. Since 2013, Ireson has been the Rothma Family Associate Curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she curated 《Temptation! The Demons of James Ensor》 in partnership with the Getty Museum. Kim completed her BA at the University of California, Berkeley, and received her MA from the University of Chicago. She has served on juries for the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award, United States Artists, Creative Capital Foundation and the Sundance Film Festival. She sits on the advisory board of the Kadist Foundation, San Fransisco, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, and West of Rome Public Art, Pasadena. She is also a researcher for the Asia Cultural Complex, a cultural organization in Gwangju, Korea. |

|

Yeon Shim Chung / Korea, Associate professor in Hongik University, 2018 Gwangju Biennale Curator Chung is an associate professor of Art Theory and Criticism at Hongik University in Seoul, South Korea. She received her Ph.D. in art history at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Dr Chung’s research interests encompass both modern and contemporary Western and East Asian art. Before receiving teaching at Hongik, Dr Chung was an assistant professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City and a researcher for the exhibition The World of Nam June Paik at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1999. She also curated several landmark exhibitions in New York and in Seoul since 2000 as an independent curator. In 2013, Chung compiled the critical anthology of Lee Yil, a major proponent of Dansaekhwa in post-war Korean art (Mijinsa, 2013; English translation published at Les Presses du Réel, 2018). She also authored several articles on Dansaekhwa at M+ Matters (Hong Kong), and monographs on Nam June Paik, Park Hyun-Ki, Lee Bul (forthcoming, Hayward Gallery, London, 2018), and Korean experimental avant-garde artists. She published a book chapter in the anthology 『Visualizing Beauty: Gender and Ideology in Modern East Asia』 (Hong Kong University Press, 2012); and has two monographs in Korean, entitled 『Installation Art in Contemporary Space』 (A & C, 2014) and 『Korean Installation Art』(forthcoming). |

Change in Curatorial practices

Yeon Shin Chung (Chung) : This year, we have multiple curators, did you see the brochure? There are so many exhibitions and venues. Can you tell us about your section? And then we can talk about mine.

Clara Kim (Kim) : Yes. First, I think that the ‘multiple curators’ is something that is happening also in other biennales, Sao Paulo for example. They also have multiple curators.

Chung : Yes, I know Sao Paulo biennale also has multiple curators, but I mean in Korea right now, they have 《Seoul Mediacity biennale》.

Kim : Right, I think that’s good.

Chung : They have like two artistic directors in Seoul and I think six curators in Sao Paulo.

Kim : Yes, I think this year is different and there is multiple curators, I don’t think we are not the (don’t have) artistic directors, but each of us are doing our own shows essentially. And the idea for my show came about because of an exhibition of project that I did in Los Angeles.

Curatorial practices and Art works on contemporary view within legacy

Chung : Yes, I saw your exhibition. It was really nice.

Kim : You did? It was the show that was part of the Getty Foundation’s PST (Pacific Standard Time): LA/LA Initiative, so it was looking at Latin America, specifically, but looking at the relationship between Los Angeles and Latin America. At that time, I did an exhibition called 《Condemned to be Modern》, which was looking at the history of Modernist architecture in Brazil, Mexico and Cuba because of the strong history of Modernist architecture there. But not from a historical perspective, but from the present. Because I think when we look back in history, we look at it as something static, something that happened in the past that doesn’t relate to what’s happening now. But in fact, I think all these things are the legacies that we have been inherited. And so many of the issues that we find ourselves in now are the results of these kinds of ideas and big government initiatives and policies and a certain way of looking at the world that we inherited after World War 2 in the 50s to the 70s.

This idea that we want to be part of a larger world, this kind of internationalist ethos that existed, and the Modern architecture becomes an interesting way to look at that, like an interesting slice of a way of looking at that because it was a very certain language in design that conveyed not just design for design sake, but it came with it a certain kind of ideology. An ideology that we are not just Korean, we are not just Brazilian; this kind of utopianism that was manifested in a new language that was free from all the weight of the past, whether it is called culture or history, colonial history, whatever. So, I thought it became a really interesting way to read these history, and to look at them from the present because we tend to think these modern utopias as a time of great hope. In fact, if you look outside of the Western world, outside the U.S. and the Europe, many of these ideas are European and Western ideas that manifested in places like Brazil, Mexico, Iraq and the Philippines. It didn’t have the same kind of development, sense of progress and a sense of social and economic progress that came with these ideas of being a modern society. So, I was interested in this - looking at it not from the past, but looking at it from the present.

* 《Condemned to Be Modern》, an exhibition of work by Latin American artists negotiating the conflicted legacy of modernism, curated by Clara Kim as part of the 《Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA biennial》.

Chung : How come you work on the architecture?

Kim :Because I have a strong interest in architecture, and because as a curator I would go to Latin America quite a bit. Since the early 2000s I was going and doing a lot of research. And what I found so striking was architecture that looked like architecture from Los Angeles, it looked like architecture from Europe… You know, there is a very different yet sense of shared ideas in a very simplified form that showed just the structure itself, which is a kind of Modernist idea. So, I became interested in this because I think if you look back in history, a lot of these things happened during a time of great change. In the case of Brazil, as you enter the exhibition, we are building it now, there is a beautiful work by Lais Myrrah. She took a detail of a Neimeyer building, it looks like this. It was one of the columns of the presidential palace of Brazilia. So she took that, but that element, it’s on a 1:1 set scale –

This architectural scale column by Neimeyer at Modernist form, she reproduced on a 1:1 scale, to real scale. But what you see is this piece of architecture and if you go behind it, what it’s being balanced by, is a column from a colonial style architecture. So, for the artist, it’s about this fact that although modernism came to Brazil, the very foundation is still quite colonial. There was no equality, no economic progress, and the thinking was still kind of embedded in a colonial history and colonial structure.

Lias Myrrah, 〈Alvorada Palace Columns〉, 1958. Architect: Oscar Niemeyer, Engineer:Joaquim. ⒸArtist

Chung : Who was the artist in L.A. who also showed the photography? One side there was a sculptural

Kim : The photography was another artist’s. And this artist is in the exhibition. He photographed Brazilia. But modern architecture also was interesting because of the spread of and dissemination of these ideas. And because Modernist architecture is so photogenic, black and white photography looks so seductive. Mauro Restiffe did these photographs using the kind of conventions of modern architectural photography like black and white, very strong contrast, except he took photographs during Lula’s inauguration in 2003 when he was the populist president. It was also another time of a really great hope for Brazil, and if you look now, even from the time that Brazilia was built in the late 50s and this sense of great hope for this country to 2003 when Mauro made these photographs was another moment of a great hope for Brazil. In contemporary history to now, so much has happened from 2003 to 15 years later, when Lula’s in jail, they are going through another presidential election and trying to nominate him to be president despite the fact that he is still in jail.

Mauro Restiffe, 〈Empossamento#9〉, 2003. ⒸArtist

I never liked architecture shows. Because I think they are always so nostalgic for design that’s so pure. But architecture lives within the public. The nature of architecture is public. So despite its purest thinking in the design and its intention, it is so susceptible to all the forces of nature, to human behavior, to politics... When you go and visit, it was very important for me to visit these sites. When you go and see Brazilia, it is very much intact and very well conserved. But many of these architectural sites are adapted, abandoned and disused. So, this trajectory was what I was interested in; not to just keep it in the past, but find out what happened to these ideas? Looking at it now, what does it mean now? And why did we think that 50 years ago? What was it that led to us wanting these modern utopias?

Chung : Your title was actually ‘Imagine the Nations.’

Kim : I was trying to change the title but couldn’t come up with another one. But many of the projects reference a time when the governments were using modern architecture to

Chung : Many of the countries were like that from the 1970s, 80s, they never fully became developed.

Kim :Exactly. So one of the artists, Seo Hyun-Suk has a film called, The Lost Voyage, which filmed the Sewoon Sangga building in Seoul that was built by the city of Seoul during a time when Seoul was being developing very quickly. And it was a kilometer-long building. This is a classic example built as a kind of commercial residential, and all the apparently sophisticated people were living there at that time. And then it quickly changed because there was an attempted assassination in the Blue House and all the development shifted to south of the Han River. That’s when Gangnam was developed. This mega structure was then abandoned and disused. Hyun-Suk is especially interested in when it was used in the 80s as the center of the black market and apparently musicians also went there to play music. So, it becomes something else. It’s that trajectory that I’m interested in and how these buildings withstood time.

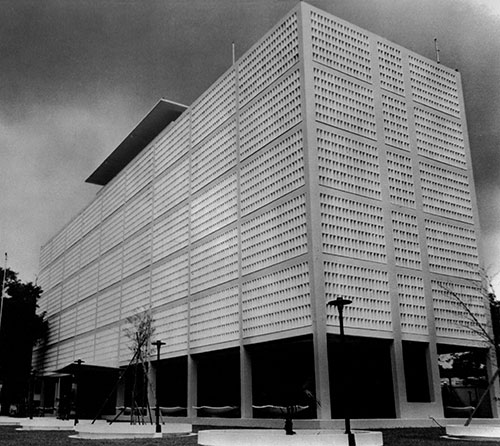

There was a city project of development, but also these state initiatives, and there was another new commission by Terrance Gawer. He is one of the few American perspectives, however, looking at the U.S. embassy building program that happened after World War 2. The U.S. government realized it needed to place itself within the global community. It started in the 50s during the Cold War period. So, it was very much linked to ideas of the Cold War. So if you think about so many history of the U.S., which I’m more familiar with, there was artwork that was sent like abstract expressionism, which also became a way to communicate ideas of American values that we know of now, that were, of course, propaganda of a different kind, but it was propaganda. And I think that U.S. embassy program also functioned in that way. And at the time, they were employing modernist architects to convey and become a symbol of American values. Within those symbols of freedom or democracy or whatever it is, there are other things at play. There is propaganda at play. There was kind of exertion of power and dominance. So I’m interested in these kinds of conflicted history that is not just modern architecture in the pure utopian form. There is no such thing. I think there are critical views of it, but I think by looking at it from the present, we can read all this. The buildings become a kind of container to read history and to read its contemporary relevance.

Seo Hyun Suk, 〈The Lost Voyage〉. ⒸArtist

Seo Hyun Suk, 〈The Lost Voyage〉. ⒸArtist

Seo Hyun Suk, 〈The Lost Voyage〉. ⒸArtist

There was a city project of development, but also these state initiatives and there was new commission by Terrance Gawer. He is looking at, which is one of the few American perspectives however, the U.S. embassy building program that happened after World War 2. The U.S. government realized it needed to place itself within the global. It stared in the 50s during the Cold War period. So, it was very much linked to the idea of the Cold Wars. So many histories of the U.S., for example: abstract expressionism in the art world that was also a way to communicate the ideas of American values that we know of now and of course the propaganda. It was a different kind, but also a propaganda. And I think that U.S. embassy program also function in that way. And at the time, they were employing Modernist architects to convey the ideas; it became a symbol of American value. Within those symbols of freedom and democracy or whatever it is, there are other things applying. There is propaganda applied. There was kind of exertion of power and dominance. I’m interested in these kinds of conflicted histories that is not just modern architecture in the pure utopian form. There is no such thing. The architectural history, there are critical views of it, but I think by looking at it in the present, we can read all these that the buildings had become a kind of containers to read history and its contemporary relevance.

Terence Gower, 〈New US embassy, Saigon〉, 1967. National Archives, Washington, DC. ⒸArtist

Ala Younis, 〈Plan for Greater Baghdad〉, 2015. two- and three-dimensional prints and a model. ⒸArtist PhotoⒸAlessandra Chemollo. Ⓒla Biennale di Venezia.

Ala Younis, 〈Plan for Greater Baghdad〉, 2015. two- and three-dimensional prints and a model. PhotoⒸDavid Heald Ⓒ2016 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

*Exhibition

Title: Imagined Nations / Modern Utopias

Curator: Clara Kim

By looking at modernist architecture, this section explores the process of constructing a national identity after the ‘Korean Independence Movement,’ revolution, and colonization in the mid-20th century. It investigates the intersection among modernism, architecture, and nation-building at a time of social and political turmoil from the 1950s to the 1970s. At the same time, it revisits utopian dreams that were rendered by a series of national development projects such as the construction of a new capital, government buildings, embassies, large-scale public housings, and university cities, not to mention urban planning projects that are common across the world. Featuring interesting works by the artists, photographers, and video artists who have remained skeptical about such history that was fooled by a sweet promise of and hope for growth and equality for all, this section aims to shed new light on how these modernist projects impact the contemporary society. It also attempts to localize and redefine the logic of modernism by looking at significant figures in modern history.

Los Carpinteros, 〈Sala de Lectura Coppelia (prototipo)〉, 2013. Corten Steel, 38.4x132.1x132.1cm ⒸArtist ⒸLos Carpinteros Courtesy Los Carpinteros PhotoⒸEduardo Morera

Shezad Dawood, 《Cities of the Future》, 2010. Installation view at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai. ⒸArtist

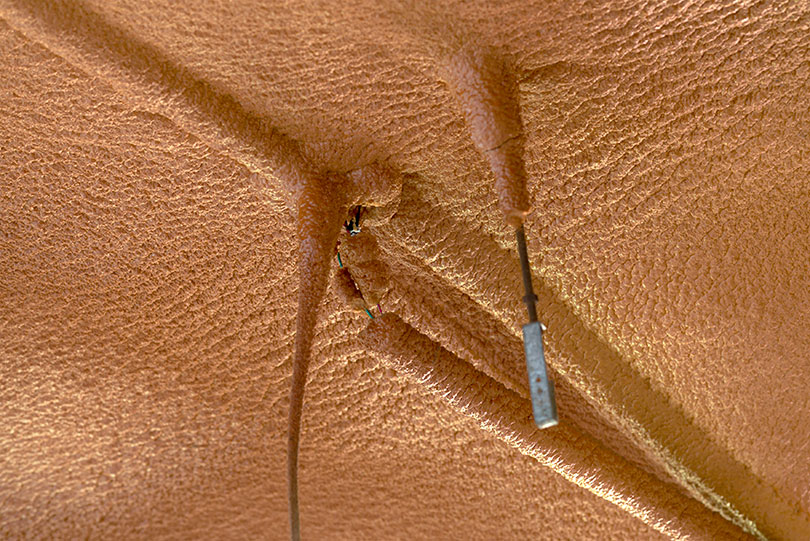

Chung : One of my artists – there are two of them:, Seungwoo Baek and Joongho Yum. They are trained as photographers and took all the pictures of the military, Gwangju Hospital and the memorial monuments. It is very interesting that Joongho Yum’s work is titled as 〈Under the Skin〉. His photos are like fragments of the space and the interior space. He said it’s like a kind of architecture skin, meaning human skin. We took the inside out and put them at the former Jeollanamdo Conference Hall. Now it is a 5.18 Monument. So we put them there. He especially wanted to put them in the basement where people stole the weapons on May 18th.

Seung Woo Back, 〈A Mnemonic System-#184〉, 2018. Digital print on canvas, 100x133cm. ⒸArtist

Joongho Yum, 〈Under the skin〉, 2017-2018. Digital inkjet Print, 10 Framed Photography, each 40x60cm; 3 site-specific installations. ⒸArtist

Damian Ortega, 〈Jirones/Shreds〉, 2018. ⒸArtist

Kim : There is another work of art called 〈Skin〉. Damien Ortega who also made a new work and he traced the floor plans of Modernist houses in Mexico and certain neighborhoods where has volcanic landscape, but they built very geometric houses in this very rocky and wild landscape. Many of these houses are now abandoned, destroyed or renovated to the point where it’s no longer recognizable. He traces the silhouettes of the footprints of these houses and cut them into leather like pieces that people can wear. When they are not being worn they are just hung from up with hook like a piece of meat, carcass; it’s called 〈Skin: the skin where you live in〉.

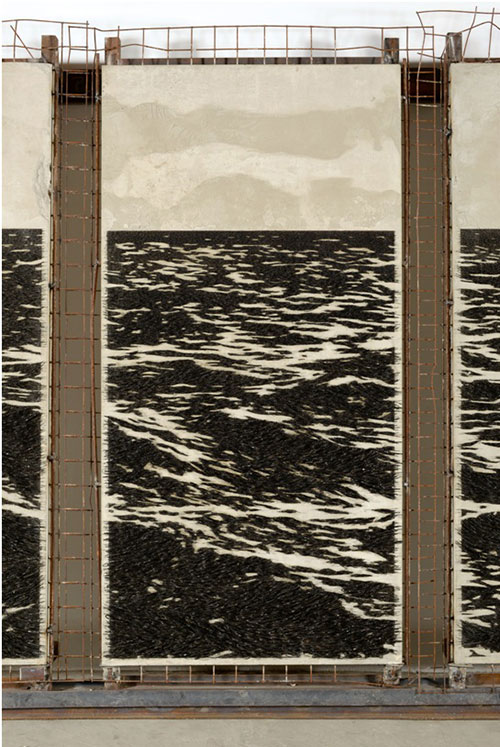

Yoan Capote, 〈Muro de Mar (Seawall)〉, 2018. 7 concrete panels, wood, metal structure, nails, and thousands of fishhooks, Each panel dimension:272x150x30cm. ⒸArtist ⒸJack Shainman Gallery ⒸBen Brown Fine Arts. Supported by Henrik Toggenburger.

Chung :Also in our show, there is another Cuban artist, Yoan Capote. there is another Cuban artist, Yoan Capote. His work weaves 7 concrete panels. It’s called 〈Seawall〉. There was a U.S.’s sanction against Cuba that Cuban couldn’t do fishing. So, they use the seawall and put the fishhooks for the people who couldn’t access to fishing. I thought it was like architectural modernist grid/greed in a way and also has political meanings. So, we are going to put them as like a circular monument.We don’t know how we will do that. It is very difficult.

Aernout Mik, 〈DoubleBind〉, 3 Screen Video-installation, 2018. Dimensions variable, ⒸCarlierGebauer, Berlin Made possible with support of the Mondriaan Fund and the Netherlands Film Fund, Collection of Maeil Dairies Co., Ltd

Kim : But I think going to back to your question of how it relates to Benedict Anderson and Imagined Boarders. I was thinking of Anderson’s Imagined Communities and the world of imagination in developing an idea of a shared nationality, a sense of belonging. For me, modern architecture also becomes part of that. Embedded in modern architecture were ideas of representing a new national identity free from its past with a future moving forward - the way that it created this idea of wanting to be there. But in fact, it wasn’t imagination. How important the imagination is in shaping who we are as people, as a community and as a nation. And I think it’s good to think about those ideas now because we are finding that nation states are quite fragile. There is more factionalism that’s happening everywhere.

*Exhibition

Title : Faultlines

Curator : Yeon Shim Chung, Yeewan Koon

Borrowing the geological concept of ‘fault,’ a crack in the Earth’s crust where rocks on either side of the crack have slid past each other as a result of plate tectonic forces, this section takes a multifaceted approach to contemporary problems that have been causing social, political, and psychological wounds by worsening old cracks or creating new ones. It aims to address the burden on future generations, namely, the symptom of social cleavages, while questioning whether we are heading for an apocalypse in the Anthropocene age, a new epoch defined by humanity’s impact on the earth’s ecosystem. The artists with different backgrounds will give answers to the problems that humanity faces based on their experiences. Focusing mainly on three aspects, namely, body, environment, and surface, the artworks featured in this section can be viewed as a collective inquiry on ‘Beyond the Borders ’(1995), the first 《Gwangju Biennale》. Taking a step away from imagining a utopian world without borders, this section will discuss the survival of humanity in depth, in a world where nothing is predictable.

Modernity on Faultlines

Chung : Yes, the formation of nation is actually modern convention.

Kim :Exactly. It’s a very new idea. We should think through this, ‘Does it make sense?’

Chung : That’s why we used Fault Line. We wanted to find those kinds of crosses, displacement and movements between different faults. So we came up with this term that we actually translated into Korean differently. Fault line is not really found in Korean very often and googled it in Korean. Only specialist is using this term. It’s very rare to use this term, in general. So I used, actually, ‘jijin.’ Because in Korea, we never had an earthquake before. But these days, it happened earthquake in Pohang city. So we believe that we have fault lines and translated as jijin.

With doing this, we bring a reality which the modern idea is on the blink. Many -ism and idea is invented such as Eric Hobsbawn tradition. Then we tend to think that tradition is a given, but it’s not really given. It’s not something that be de-constructed.and we thought it really goes along with Anderson's.

Kim :I was also reading Walter Mingnolo, who is Argentinian and based in the U.S, and he has been writing about de-coloniality. And his basic argument is that one side is Modernity and the other side is colonialism. There are two sides of same thing essentially. I think this is so important for us to look at because we tend to think that modernism was an inevitability, like of course every nation should be modernized. But what comes along with those ideas was a form of colonialism as well.

Chung :We can add one more since Korea went through the Japanese Occupation. They can say modernity and colonialism, but I made this term, vernacular-ense or indigenous. It is also an essential reason for culture, but there is a kind of thing where colonialism is forced to be maintained, so it’s another kind of identity.

Kim : Yes, Walter Mingnolo also took things to talk about this too.

Chung :What kind of term does he use?

Kim :Indigeneity. I think everywhere there is a kind of movement of going back to think about indigenousness or traditional roots. What it signals is the desire for something else. Because modern progress didn’t come to other nations due to many reasons.

A lot of more interesting local regional architects are going back to their more indigenous roots. There are African roots, their vernacular traditions, ways of building and making with natural materials. And some of the art works in the show reference this too. The vernacular with modern together; this combination is really interesting.

Chung :In architecture, it’s very prevalent. They use vernacular actually as a term, right?

Kim :The vernacular with modern together. This combination is really interesting.

Architect like Lina Bo Bardi, an Italian immigrant who settled in Brazil - she was so interesting. Because she wasn’t just taking these ideas of Western modernism, Corbusier-an ideas, and transplanting them into Brazil. But she recognized the fact that the places and materials are different and history and people are different. So, she often returned to the African roots of Brazil and built it with a very natural materials with this in mind. And I think those architects become more interesting. But again, the show doesn’t have any architect. It’s really the artists who are looking through this history.

Leonor Antunes who is interested in these modernist figures who are lesser known, like Nina Bo Bardi, and especially women architects and designers. And she is using conventional, vernacular ways of making things and forms, like ways of making knots and fishing nets made in traditional ways. She is referencing that kind of history in different ways. Not everything is critical but in different ways.

*Lina Bo Bardi, (b. 1914 – 1992) was an Italian-born Brazilian modernist architect. A prolific architect and designer, she devoted her working life, most of it spent in Brazil, to promoting the social and cultural potential of architecture and design. Leonor Antunes who is interested in these modernist figures who are like Nina Bo Bardi and especially women architects and designers. And she is using the conventional, vernacular ways of making things and forms like ways of making knots and fishing nets made in traditional way; she is referencing that kind of history in different ways, not everything is critical but different ways.

Leonor Antunes, 〈A secluded and pleasant land, in this land I wish to dwell〉, 2014. ⒸArtist

On biennale’s system and its potential

Chung : Then maybe we’d better talk about ‘multiple curatorial practice.’ You are working at Tate Modern institution. Biennale is of course different. How do you find different to work with other co-curators.

Kim :For us, Gwangju biennale, this time around, they are conceived separate projects, so there wasn’t so much collaboration between us. It’s been nice for us to share the same platform in various ways, but also nice to have our own freedom to develop the exhibitions with multiple co-curators, where we have to come up with a consensus. That’s a different process that I can require more lead time. Because this year was such a short lead time to do an independent project I think.

And I also think maybe biennale is becoming too big.

Chung : Like a Tate Modern.

Kim : I think what’s different is that institutions build over time. Like Tate has been around since 1897. I mean, Tate Modern opened in 2000. I think the function of museums and biennales are totally different. Why I wanted to do the biennale is because I don’t get to work this way at the Tate. At Tate, everything you build takes slowly over time with a collection and when you have to consider something it takes like 2-3 years, you spend 2-3 years researching and developing exhibitions… Yes, things move very slowly.

Yes, they are getting bigger, but institutions carry a history over many decades and centuries sometimes. These two have a different function in society. I think it’s because, yes they are bigger, and there are great interests in art in a way that there wasn’t when I started art 20 years ago as a curator. Nobody went to museums. But now everybody goes and I think that is a very positive thing. It’s a big responsibility to be an institutional curator and think about what you do when you have that kind of public willing to come to your institution. I think it’s about thinking through what we do, and for Tate, as an international institution, how we tell international art history in a way that is broad and expansive while telling about the diversity of modern contemporary art history. That’s what makes my job enjoyable and gratifying because I get to push, not just look at New York in the 50s, 60s and even 70s, but to look elsewhere, see what is happening now.

Biennale is different because you can be more responsive, you can work more quickly, you be very contemporary and it makes you use a different part of your brain to think quickly on your feet, be creative, work with a lot of people, work with a lot of artists and I enjoy that.

Chung : And museum exhibitions often can be limited to nations. Biennale comes up with very different issues in different locality.

Kim : But Tate is not trying to do that, not to just do China or Latin America exhibition. But we will do looking at trans-national histories. My job is very interesting cause it’s not just looking at one area, but connections between cultures and between artists, especially outside of the West. We know the history that artists going to Paris in a certain time. I like the connection happening between Seoul and Tokyo and other parts of the world.

There is a fact that we have a too short of time to lead, which is a criticism we have and that maybe there isn’t the opportunities to see really clear relationships because everything is happening at the same time and being strategized.

The idea that one person can think about the entire world and be able to make a grand statement about what’s happening in this world especially now is very complex. The shows I most enjoyed was ones that is more modest in scale and say something that are more engaged.

So, I think that biennales have to change actually. I think that biennales, as we know it, grew from the 90s, going back to the history of the Gwangju Biennale, starting at a very different time when there were not so many international exhibitions and there was a great sense of hope that we are living in such a connected world and there was a desire to go beyond the world.

So we ask why we thought those things at certain times and that changes over many decades. Why didn’t we think like this in World War 1? Because it went a very different way. Global and capital got concentrated so much and nobody thought about its impact and now we have to think about them in a different way.

I think art world has, to be more specific, in both institutions and biennales, it that we have so much capital in the art market. You can read about these crazy figures on how much money is exchanged within the art market. Yet institutions, museums and biennales are all suffering, artist even. It’s not balanced. I think it’s a window to the situation more generally and economic issues more globally. And I think we have to rethink that because we can’t continue on like this otherwise art world/artists will look at something else. It’s happening everywhere.

Chung : The last question is what do you think about the problems of biennales? I think it is problematic. But it’s also very hard to find solutions. We tried many different methods for example, using multiple curators and if it doesn’t work, we might go back to one artistic director.

Kim : But what I think it’s important in biennale, unlike institution, is that it should experiment. It should respond to the time. Museums cannot always do that. It has to look at history and has to make sure something that’s important now and in 30 years- we have to think that way actually. I think biennale is different; it’s the platform made to be responsive to where we are living in. Also by nature, we cannot solidify what biennale is, but in fact, we have to shake it off and try something else.

Yeon Shim Chung

Associate professor of Art Theory and Criticism at Hongik University in Seoul, South Korea.