TheArtro looks back at the Korean art world in 2016 in this special year-end review article. The year 2016 saw a bounty of diverse exhibits rolled out in time for the season of major biennales, which comes once every two years. While enthusiasm for Dansaekhwa in the arts market and among arts institutions continued unabated, concurrent efforts were made to explore post-Dansaekhwa art, enabling the rediscovery of prominent artists who had been otherwise underappreciated. Outside of the art world, numerous incidents took place that reflected the current sociopolitical issues facing the country. This article looks at this array of trends and what they say about where Korean art stands today.

Looking Back on the 2016 Art World

Every year is packed with memorable events, but 2016 seems to have been exceptional. The sexual harassment incident that erupted in the art world in the second half of the year, the hobbling of the culture and arts communities that emerged in the wake of the Choi Soon-sil scandal—it’s been a year that has left issues involving behind-the-scenes power running through people’s heads. In reality, major feature exhibitions, such as the biennials that tend to all be held in even-numbered years, are also a power issue. This is not to say that power is entirely a bad thing. Ever since the argument that modern ideas like post-structuralism are closely tied to discourse and power, the power-discourse complex may be seen as offering themes for the various biennial events and the works in them when power is seen in terms of its positive, “producing” aspect, rather than the established position viewing it as merely oppressive. The difference is that as these biennials and other large-scale feature exhibitions become the subject of some form of scrutiny as part of a debate in the arts community, things like sexual harassment and government interference, which were once carried out at by powerful figures behind a veil of secrecy (until they were caught, anyway), are subjected to judgment by the law for the trail of damage they leave in their wake.

Discourses on the arts community sexual harassment situation exploded at all once over social networking services, illustrating how the relationship between sex and power can no longer remain secret in an environment where private life becomes public in real time. Occurring as it does in relationships of power imbalance, sexual harassment is but one of many irrational practices inflicted on a younger generation just entering society amid a system of highly organized capitalism. The case also showed the younger generation—the focus of some emphasis in 2016—and the dark side it carries with it. The government interference scandal, which involved “secret forces” bearing ties to the top echelons of power, was a matter of particular interest for artists; involvement by a public institution meant that they would inevitably be affected. Quite a lot of things ended up subsumed in the scandal. One of the big trends in 2016 exhibitions (outside of the various biennials) was how surprisingly many exhibitions involved figurative art, an approach previously relegated to the periphery amid the monochrome wave. In the midst of all these bigger and smaller exhibitions lurked the issue of another aspect of power, money, as shown in cases involving forgeries, masterpieces, and record-setting sellers.

Left) ORLAN, ‘Bejing Opera Self Hybridization n°6’, 2014, ORLAN, Augmented Reality, Beijing Opera, Augmented Reality, Exhibited at 2016 Busan Biennale.

Left) ORLAN, ‘Bejing Opera Self Hybridization n°6’, 2014, ORLAN, Augmented Reality, Beijing Opera, Augmented Reality, Exhibited at 2016 Busan Biennale.Right) Suh Yongsun, ‘Collective Consciousness-People of the City’(detail), 1989, Vinyl on Canvas, 400×385cm.

A Year of Biennials

September 2016 saw a veritable flood of arts events held in places like Seoul, Gwangju, and Busan, all opening around roughly the same time. There were also a number of quite large arts events staged at an international level, including the Geumgang Nature Art Biennale and the Changwon Sculpture Biennale. Around the same time, arts magazines began printing related articles and comparing the events. With the biennial season all happening in the space of around two months, of course, the discourse surrounding them tends to evaporate quickly. Since it’s beyond the scope of this short text to look back on an entire year of art and analyze the topics and works of art presented at each of these biennial events, I will state up front that it is simply an impression based on a few memories that it left behind. Despite differing in themes, the different events this year share questions about their relationship with the works that actually appeared in them. This is certainly not to diminish the stature of the individual works of art on display or the artists invited to participate. Art directors are commissioned after a selection process, doing their utmost to liaise with and invite artists and artworks to which their influence extends.

The problem, however, is that once art is actually assembled in one place, it speaks with one voice; what it fails to do is produce a feeling that resonates with the exhibition theme suggested by the organizers. If at least a few of the works leave a particular mark, it may be possible to glean some meaning from viewing them—with the investment of a lot of time, that is. I certainly don’t see that as impossible. But do there really have to be so many different works of art together to achieve that? Local governments have scrambled to stage major arts festivals, their mindset something along the lines of “They do it in that country, so we need to do it here too,” or “They’re doing it in that region, so we’re going to do it here.” The results have all been of similar scale, with similar patterns. It’s a wasteful practice, something we might call a form of large-scale visual consumption, and one has to wonder how long it can last.

Just as artists agonize to some extent in creating their work and assigning subtitles to their exhibitions, so art directors go through more or less the same thing. A case in point is “NERIRI KIRURU HARARA” at SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul, which seemed to adopt the same strategy for exciting consumer curiosity as a new product given an obscure brand name that leaves people unable to guess what purpose it could possibly serve. It’s the same thing as having to recognize brand names when you want to buy a popular shade of pink lipstick: “I want Rosy Lady at Play Impassioned Relentlessly Red Number So-and-So.” The name “NERIRI KIRURU HARARA,” which sounds like some kind of alien speech, obviously holds significance, sending the message that we should approach contemporary with a more proactive stance of learning. The same can be said for the ambiguity in the Gwangju Biennales “The Eighth Climate: What Does Art Do?” This is true even when we consider a hundred times how contemporary art is never complete, how it’s a language in process. The artistic director at Gwangju explained that the title “refers to a medium variable rather than a theme or concept”—but that borders on meaningless, both in terms of the “medium” and in terms of the “variable.” If there isn’t a proper medium, there are all too many “variables” that arise. Behind the theme offered for the Busan Biennale, “Hybridizing Earth, Discussing Multitude,” was a strategic move where any unified meaning was ruled out a priori. But there remains the question of why that exhibition was tied together with another titled “an/other avant-garde china-japan-korea,” which looked at the period prior to the 1990s.

Left) The Winner of Hugo Boss Prize 2016, Anicka Yi, ‘Fontenelle’, 2015, Various materials, Dimensions variable, Exhibition view at Gwangju Biennale 2016.

Left) The Winner of Hugo Boss Prize 2016, Anicka Yi, ‘Fontenelle’, 2015, Various materials, Dimensions variable, Exhibition view at Gwangju Biennale 2016.Right) Project by Ham Yang Ah, Installation view of the Summer Camp “The Village”, 'Recollection Archive', 2016, Commissioned by SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016.

Self-Conscious Exhibitions on the Monochrome Battle, Forgeries, and Masterpieces

The greater stature of monochrome painting in Korea, Dansaekhwa, and abroad resulted in a number of reciprocal exhibitions in figurative art, which differed in character and amounted to a rebuke of the Korean arts community. Seemingly every artist worth his or her salt took part, from members of the Minjung art lineage to those practicing figurative art of a rather critical bent. Exhibitions of Dansaekhwa and other abstract art started early in the year with a special showing of pieces donated by Seo Se-ok at the Seoul branch of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, and continued with events on the work of Kim Hyung-dae (National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon) and Kim Taiho (The Leeahn Gallery, Daegu). The Kim Daljin Art Research and Consulting held a historical exhibition on Korean abstract art centering around detailed sketches of individual artists. In an associated event, the critic Yun Jin-seop, who played a theoretical role in the Dansaekhwa wave, gave a presentation on the “Birth and Evolution of Dansaekhwa.” Around April of this year, I gave the following response to a Kim Dal-jin Institute survey asking for my “overall opinion on the future stature and trends of Korean abstract art amid the recent interest in Dansaekhwa”:

"In a recent exhibition, Park Seo-bo, who has been called one of the most representative monochrome artists, said that color is the most important thing in his work. As this suggests, the Korean Dansaekhwa that has received such attention recently at home and abroad focuses on color to the exclusion of other elements that may be seen as secondary from a modern aesthetic perspective, including theme and shape. At root, it is a reduction to the minimum needed for maximum effect. Another crucial thing is the texture needed to bring a greater variety of nuance to that color. When modernism is reduced to color or texture, it takes on an ornamental or formalist tendency. But monochrome, which has been called a “Korean style” of abstract art, concerns color applied to a distinctive texture. By bringing out the potential strength in painting that fits with no other genre, it has been able to shine brighter in an era of high-chaotic diversity than it could in the era when it first emerged."

Abstract art’s popularity has continued to the end of the year: in a Seoul Auction bidding in Hong Kong on Nov. 27, a piece by Kim Whan-ki, covered in yellow spots went for HK$ 41.5 million, setting a record for the highest-valued transaction in Korean art history. Indeed, the top five spots now all belong to abstract works by Kim.

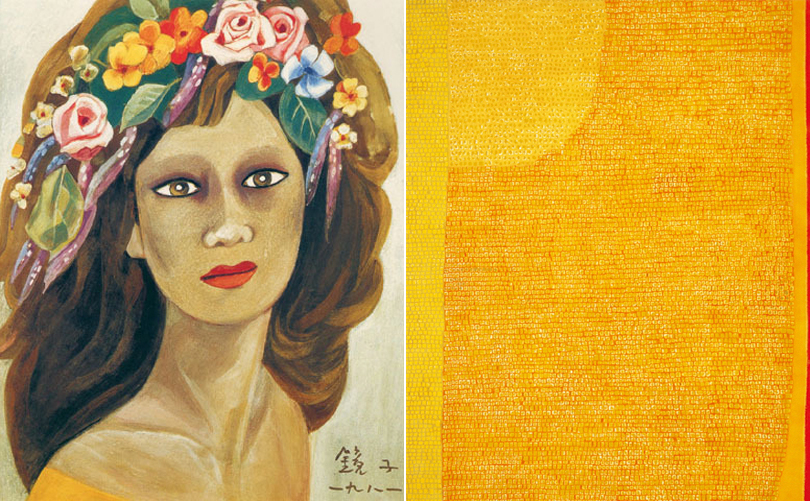

Left) Chun Kyungja, ‘Beautiful Woman’, 1977, Waterolor on Paper, 29×26cm.

Left) Chun Kyungja, ‘Beautiful Woman’, 1977, Waterolor on Paper, 29×26cm.Right) Kim Whanki, ‘Untitled 12-V-70 #172’, 1970, Oil on Cotton, 236×173cm.

Even if bidding prices aren’t the only way to gauge a work’s value, they’re a crucial index. The reason this year’s figurative art exhibitions—comparable as they are to Dansaekhwa—gave such a retrospective impression may stem from a self-conscious attitude toward a broader assessment that seems to be progressing backward in time. There’s competition in every field, and competition in art may be all the more productive for the way it values difference more than other fields do. A number of exhibitions held between late 2015 and early 2016, including “A Broken Wing: Ahn Chang-hong 1972-2015” (Arario Gallery), “Park Bulttong 1985-2016” (Gallery 175) and the Oh Chigyun exhibition “New York 1987-2016” (Kumho Museum of Art), were of a retrospective character. Suh Yong-sun, a former professor who has been prolific as an artist since entering the field, has shown his potential with three large and small exhibitions this year, including “Expanding Lines: Suh Yongsun Drawing” (Arko Art Center), an exhibition featuring a “selection of around 700 out of over 10,000 works of drawing done since the 1980s,” along with his display of wild wood sculptures with “Color and Emptiness” (Kim Chong Yung Museum) and his Mt. Inwangsan-themed exhibition at Nook Gallery.

Also representative of a trend of figurative art resistance against the monochrome vogue were the Choi Jin-wook exhibition at Indipress, the Kim Jung-heun exhibition at Art Space Pool, the Min Jung-ki exhibition at Kumho Museum of Art, and the Shin Hak-chul exhibition at Hakgojae. While his work may fall in the figurative art vein per se, Kim Yong-ik has adhered to a critical modernist perspective in a different context from the abstract art trend represented by monochrome; chances to view his work as a whole have been offered at exhibitions from the Ilmin Museum of Art to Kukje Gallery. Controversies over historically high prices, forgeries, and masterpieces offered a perfect opportunity for the public to get involved in abstruse contemporary art discourse, drawing mass media attention out of proportion with their actual importance. Perfect examples of this were the debate over supposed use of ghost-authorship by singer-cum-artist Cho Young-nam and the controversy over the authenticity of works by Lee U-fan and Chung Kyung-ja. These “scandals” raised questions about the subject of art. Is it real because the artist says it is? To what extent should we view the artist as having “directed” a work of art?

Lee Sun-young / Art Critic

Lee Sun-young began her criticism career in the Chosun Ilbo’s art criticism category in 1994. She has served as an editorial board member for Art and Discourse (1996--2006) and editor-in-chief for Art Critics (2003--05). She also sat on the committee for the Art in City project (2006--07) and was an advisor for the Incheon Foundation for Arts and Culture’s local community cultural creation program (2012--13). The Awards include the 1st annual Kim Bok-jin Art Theory Award (2005) and the first annual Korean Art Critics’ Association Award for theory (2009).