When and how did Korean artists adopt video as a medium for artistic expression? What were the internal and external environments of that art? What is the context of its development in relation to Korean art? Yi Won-Kon, a media theorist and member of the first generation of video artists, examines 30 years in the history of Korean video art from the 1970s to the 1990s based on his research findings and his own experiences as part of that scene. From his perspective, pioneers of the Korean video art in 1970s focused on video as a tool for contemplation and creation within the context of avant-garde experimental art. With the influence of Nam June Paik and popularization of the video medium, the mid-1980s brought the emergence of works that explored video’s medium-specificity or combined it with sculpture and installations. During the 1990s, video art underwent expansion in form and content under the influence of the postmodern discourse introduced from the West. Within these historical currents, Yi provides a detailed analysis of the works featured in the 《Korean Video Art from 1970s to 1990s: Time Image Apparatus》 exhibition.

Kim Beom, 〈Untitled (TV Microwave)〉, single-channel video, 1 min. 59 sec., 1991_Kim Beom has used a diverse range of media including painting, drawing, sculpture, and video to appropriate ordinary objects, scenes, and phenomena with humorous nuance, posing questions about the irrational relationship between human beings and their world. Image Provided by Art In Culture

“The origin of painting,” a popular theme for Western painters in the 19th century, is a story about Butades, a potter’s daughter who traces along the shadow of her departing lover, which her father turns into a relief. Interpreted in this context, painting is a “technique for visualizing something which is(was) originally present but is no longer seen.” There is also another version of the story presented in Pliny the Elder’s 《Natural History》, which describes how the painter Zeuxis created an image of Helen by using the most beautiful features from five maidens on the island of Croton, but all of the countless images of deities painted or sculpted at shrines and temples around the world, and all of the images that record historical incidents, are visualizations of worlds that exist unseen or worlds that are believed or imagined to exist. In other words, artists have drawn upon all of the knowledge available to them to visualize the “truth”—a practice no different from the scientific visualization or data visualization of the contemporary era.

It seems to be a globally recognized fact that a new path to artistic expression has been opened up by new media and media technology. That technology and those media, moreover, determine our ways of seeing and the observed forms of truth. Everything is “mediated reality.” Whereas media such as cinema and television demanded a specific manner of viewing from people, artists have disregarded this to approach their media through different means; they have gone through processes of transforming and optimizing them into means of creative work. Indeed, latter-day artists, who have not been technological specialists, have encountered media that were developed and experimented with long ago, their flaws corrected and perfected and their forms already commercially mass-produced. Here, artists demonstrate their latent gifts as creators. (Recall how ars and techne came from the same etymological roots.) By appropriating and “hacking” media, artists have turned the widely used universal technology into “unique technology” exclusively for them. The televisions used by Nam June Paik in his exhibition 《Exposition of Music – Electronic Television》 (Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal, Germany) in 1963 were “prepared TVs” like the “prepared piano” produced by Paik’s mentor John Cage. By disrupting and appropriate the various features of CRT, he produced 12 different TV sets. This sort of hacking would reach its zenith with the video synthesize that Paik co-developed with Shuya Abe, and the “video art” genre achieved concrete shape as a result.

While Nam June Paik referred to his own technology as “sloppy,” it was utterly undeniable cutting-edge technology to Park Hyun-ki, who was living at the time in 1970s Korea. Despairing, Park turned his focus in an entirely different direction as he devised means of introducing the televised image into his “non-material structures” as a kind of art object. Parallel to this process of new media being appropriated by artists were the new or idiosyncratic techniques used with those media. To be sure, some of the Korean video art of the 1970s to 1990s does not fit with the perspective described here, as with single-channel video and other inheritors to the experimental film spirit. In this piece, I will be examining the Korean video art works produced between 1970s and the 1990s that are explored in the exhibition 《Korean Video Art from 1970s to 1990s: Time Image Apparatus》 (Nov. 28, 2019–May 31, 2020, MMCA Gwacheon), focusing in particular how the methods through which Korean video artists appropriated the video medium for the purposes of their own artistic expression.

The Beginnings of 'Video Art'

In 1952, the US mathematician/scientist/artist Benjamin Francis Laposky used a cathode ray oscilloscope (a form of cathode ray tube [CRT]), sine wave generators, and other electronic circuits to obtain abstract images that included sine waves, square waves, and Lissajous figures, which he captured with photographs. His work became widely known through a US and European touring exhibition titled 《Electrical Compositions》 or 《Electronic Abstractions》. This was an event that illustrated how CRT technology had become a means of artistic expression. In 1963, Nam June Paik hacked TV receivers and modified them in different ways to show new possibilities for the electronic image in his exhibition 《Exposition of Music – Electronic Television》. With his 13 televisions, he either (1) disrupted the CRT’s scanning line deflection mechanism or tampered with the set so that the vertical and horizontal synchronized signal circuits operated in different ways, or (2) transformed the screen by juxtaposing musical signals from a radio or tape recorder with a video signal that had undergone a process of detection and amplification with a tuner.

Nam June Paik’s actions could be characterized as “hacking (completed) technology”—a form of appropriation to a different use from the originally designed purpose. In technological terms, it was indeed “sloppy,” but his approach seemed to carry on the legacy of Paik’s mentor John Cage’s “prepared piano,” and the “string piano” of Cage’s mentor Henry Cowell before that. Thanks to this vision presented by Paik, the term “electronic art” entered parlance alongside “TV art” or “television art”. But despite the market launch of Sony’s Portapak in 1965, the term “video art” was not used at the time. The first employment of “video art” as a term would only come after the period from 1969 to 1970, which saw the full-fledged development of video synthesizers by Paik, Shuya Abe, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and tephen Beck. 〈Global Groove〉 in 1973 was a representative work heralding the arrival of the video art era, while also serving as inspiration for the video art experiments of Park Hyun-ki back in Korea. 〈Good Morning, Mr. Orwell〉, which was broadcast on January 1, 1984, shared similarities in its content and was a major influence on Korean artists.

The word “video” refers originally to the “visual,” but the name is used to refer to the analog video-based recording and playback media used in the 1960s to 1990s. It is an appellation that refers to the medium as such. The late 20th century witnessed a trend of other genres being referred to by the name of their medium, such as “holography art,” “CG art,” “laser art,” or “satellite art”—a powerful reflection of the belief that the properties of a medium almost fully determine the character and expressive characteristics of the associated artistic genre.

The following period would see the use of many names that focused on the properties of media and the information that they incorporated, such as “information art (info art),” “cybernetic art (cyber art),” or “digital art.” Another trend has involved names that focus on methods of communication, including “communication art,” “network art (net art),” “telematics art,” “web art,” “internet art,” and “interactive art.” The general practice today, however, has been to refer to all of these areas as “media art.” So when we speak of “video,” this refers to the analog recording and playback devices used in the 1960s to 1980s (such as VHS, Betacom, and U-matic), and we may therefore assume that “video art” more generally denotes artistic activities based on those media.

Kim Ku-lim, 〈Civilization, Woman, Money〉, single-channel video, color, sound, 22 min. 10 sec., 1969/2016_The first Korean avant-garde film, designed in January 1969. When production first began, the topics included the inhumanity, indolence, degeneration, comforts, and enjoyment stemming from the modern individual’s materialism, but the project ended up being halted after the actress refused to take part in the filming. Its design is seen as an attempt to use new media and forms to express a critical consciousness regarding Korea’s rapidly changing society. It was finally produced in 2016. Image provided by Art In Culture

Tool for Conceptual Art Praxis

The 1960s in the West, with its proclamation of and experimentation with meetings between technology and art, and the transitional period in Korea through the so-called “informel movement” to the monochrome era of the 1970s saw a trend of minimalism and intensifying influence from the Mono-ha. It was a period that sent shock waves through society as the different forms of “experimental art” presented viewers with new and unfamiliar forms of contemporary art. The EAT movement, which began in the US in the early 1960s, had developed by the end of that decade into a global network with some 6,000 members. The movement reached its pinnacle in 1970 with the Pepsi Pavilion at the Osaka Expo, a six-month-long event in neighboring Japan. While no data are available to examine how the trend was introduced to Korea, the context described here is believed to have been a considerable influence.

In Western societies, the cinema genre was regarded as an inheritor to the photography aesthetic, one that included its own video aesthetic that had been developed over many years. Since the emergence of Hollywood, film had grown to become an enormous industry, with a base of young and/or experimental directors who needed a forum for personal or experimental films that would allow them an easy way of presenting idiosyncratic work, while providing a source infusing the film industry with new spirit and techniques. The earliest surviving experimental film in Korea is 〈Hand〉 (1966), a 50-second short filmed on black-and-white 35-mm film by “Cine-foem”, an association formed in 1964 around director Yu Hyun-mok, and submitted to an “international culture and experimental film contest” organized by the Montreal Expo in 1966. Other groups that were formed included the “Korea 8mm Society” in 1970, the “Small-Scale Film Association” and “Film Research Society” in 1971, and the “Kaidu Experimental Film Group” in 1974; the period also saw Korea’s first experimental film production and experimental film festival. In general, the experimental films of this period were a form of resistance against the government-controlled films that Koreans had long become accustomed to, including so-called “enlightenment films” and “Daehan News” promotional films. Additionally, they are seen as having pioneered an experimental video aesthetic that commercial cinema would never have been able to accommodate.

The video art that began to emerge around the same time is often compared to experimental cinema in terms of their both being “experimental video images”. In point of fact, however, experimental film and video art shared little with respect to their starting points: whereas experimental cinema had been an alternative movement in response to the films that were already dominant as a vast industry, video art was adopted as part of the avant-garde art movement. Film had long been beloved as a form of state and popular entertainment, and so-called “policy films” and commercial cinema were enjoying a heyday under the strict censorship of the military regime at the time. While experimental film represented an outpouring of energy in response to this (chiefly among small-scale associations), television and video were treated as the time as “inferior” media to film. Because video was seen as a method of avant-garde art, it was regarded by the film world as a medium unworthy of attention, while the entry barriers to film production were too daunting for more artists.

In that sense, Kim Ku-lim, who experimented with video production while producing television commercials at his workplace, may be seen as representing a special case. His 〈The Meaning of 1/24 Second〉 (1969) used frame editing to present images of a South Korean environment transformed by urbanization and industrial society, the daily lives of the Koreans, and powerless city residents; in its mechanical reconstruction of ordinarily lives within a mechanistic environment, it is comparable to Fernand Leger’s 〈Le Ballet Mécanique〉 (1924). The two media of film and video were sometimes combined, as in the case of Kim Duk-nyun, who presented an 8mm work at the 《Seoul 70》 exhibition in which he photographed himself as he filmed; he would go on to produce video work through the late 1980s.

Kim Duk-nyun, 〈Untitled〉, video installation, variable size, 1988/2019_This work experimented with video feedback effects by layering an identical image over top of the Mona Lisa on the TV screen and projecting it onto the wall. Image Provided by Art In Culture

Spaces between the Real and Imagined

It was a natural development for artists to focus on video, which was a more accessible tool than film and had begun to enter wide distribution in the 1970s. Video allowed for immediate playback upon filming, and because the cathode ray tube emits its own light, it does not have to be used exclusively in dark settings. Also, because the monitor could be easily incorporated as an object within settings of artistic experimentation, it offered the convenience of usability even outside of special environments such as movie theaters. But video at the time was considered to be kitsch, a cheap medium that was intended for popular entertainment, with inferior picture quality to film; psychologically, it was some distance removed from “legitimate” genres such as film and art. For the most part, arts adopted video as a tool for avant-garde and conceptual art praxis, rather than viewing it as an expressive tool for a new moving image aesthetic. As can be seen from the way video served as a means of recording and playing back performances in the avant-garde work presented in Korea by France-based Kim Soun-gui in the late 1970s, video was, through the 1970s, a recording medium—in Kim’s case, at least—for the practice of conceptual art, one that could be used in more dynamic environments than film. Kwak Duck-jun, who submitted his work alongside Nam June Paik to the 《Impact Art Video Art 74》 event in Lausanne in 1974, presented several video works from 1973 onward. His 〈Self-portrait 78〉 (1978) was a single-channel video work that aesthetically expressed his identity as a Zainichi Korean (a Korean living in Japan). Even so, video art could not be said to have represented his main field of activity.

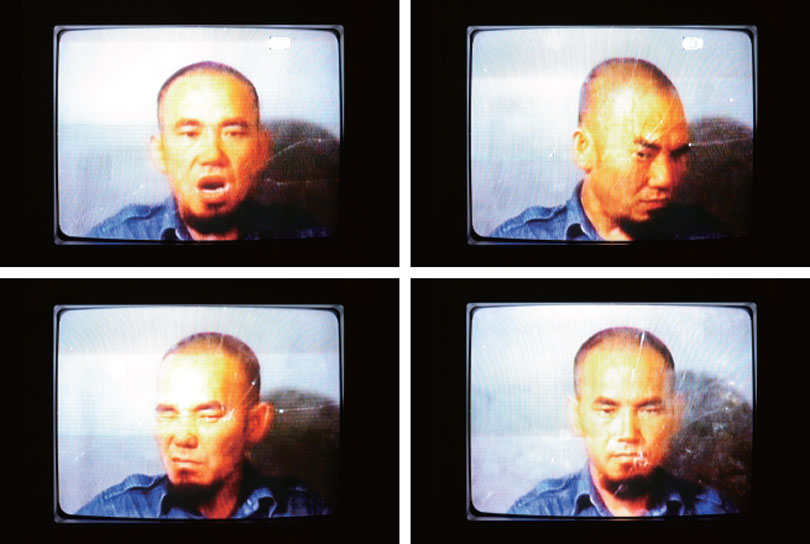

Kwak Duck-jun, 〈Self-portrait 78〉, single-channel video, 12 min. 51 sec., 1978_A Zainichi Korean artist from Kyoto, Kwak Duck-jun began adopting video as his principal medium in the early 1970s to produce works that recorded his own conceptual performances. In the work, the artist repeatedly engages in the action of violently smashing his face against a cracked pane of glass. His performance is an interrogation of his own identity as someone not fully recognized either in Korea or in Japan. Image Provided by Art In Culture

As seen here, as late as the 1970s the adoption of video art was for the most part simply as a supplementary tool for conceptual art praxis. After seeing Nam June Paik’s 〈Global Groove〉 in 1974 at the US Culture Center in Daegu, Park Hyun-ki developed his own ambitions of pursuing video art, and while he initially despaired at the realization that he could never rival Paik’s technology, he presented a work for the《Daegu Contemporary Art Festival》in 1977 that positioned a monitor facing upwards so the image of a lamp reflected in water appeared like an image of a lamp actually reflected in a tray. That reflective image would lead to Kim’s “mirror work” on the Nakdonggang River, which combined the river’s surface with an image of its reflection; the artist himself felt that his work was not “video art,” as it represented a different approach from the Western one. His 〈TV Stone Pagodas〉, which would become more or less his trademark work, was initially produced by inserting a modeled “artificial stone” of transparent material amid natural stones. It was around this time that he happened to encounter information about Paik’s video art at the US Culture Center in Daegu, which he was greatly inspired by. The very next work that he produced was the 〈TV Stone Pagodas〉, with a television receiver positioned among natural stones. With this work, he would go on to participate in the 1979 São Paulo Biennial and the 1980 Biennale de Paris, cementing himself of one of Korea’s representative video artists.

The various works that Park Hyun-ki presented appear to have their origins in a contrast between the spaces of reality and the “illusory essence” of the moving image itself. It is matter of eliciting coexistence and reconciliation between the material and non-material, drawing connections between real spaces or objects and the imaginary spaces stored in a frame such as a mirror or monitor, just as the television receiver presents images through a rectangular frame. Starting out as mere reflections, Park’s video images encountered architectural or formative spaces (which may be viewed as natural in themselves) to produce a new kind of space where the real and imaginary interact—a space between, or “interspace.” Real space is interpreted as an extension of imaginary space, and imaginary space is interpreted in terms of its relation to real space, thus producing a new space in which real and virtual are intermingled. Park’s approach is also evident in a performance at his 1985 solo exhibition at Tokyo’s Kamakura Gallery, in which the nude artist embraced a monitor and caressed pornographic images of a woman’s body on its screen.

These installations that assemble fictional, imaginary, or surrealistic worlds paralleling reality into a single structure would become a common characteristic among later Korean video artists. This is exemplified by Nah Kyungja’s 〈O.T.〉, an installation from the 1990s that once again created an encounter between the real and imaginary, or the eye in works such as Yook Keun-byung’s 〈Sound of Landscape + Eye for Field=Rendezvous〉 (1992), which is both a symbol of communication between this world and the next and a spiritual nature that monitors history and reality.

Park Hyun-ki performing during a solo exhibition at Kamakura Gallery, Tokyo_Park Hyun-ki established a sui generis place for himself in Korean video art history by placing actual stones side-by-side with video images of stones, using them to explore issues of “technology vs. nature,” “reality vs. illusion,” and “original vs. reproduction.” Image Provided by Art In Culture.

Yook Keun-byung, 〈Sound of Landscape + Eye for Field=Rendezvous part.1〉, mixed media, 800 × 720 × 620 cm, 1992 (Installation view at documenta IX, Kassel, Germany)_Adopting a “post-modernism” orientation as a member of the small group “Tara” during the 1980s, Yook Keun-byung has engaged in artistic activities spanning multiple media, including installation, video, and photography. With this work, he followed Nam June Paik as the second Korean artist to take part at the documenta exhibition in Kassel Germany. The “eye” motif is both the perspective of a spiritual presence existing through the past and presence, as well as a medium encompassing all dichotomies. Image Provided by Art In Culture.

After the 'Nam June Paik' Shock Wave

Returning to the Korea of the 1980s, we find what might be described as a “period of enlightenment” for Korean video art—a phenomenon that bears some connection to the presentation of Nam June Paik’s work in Korea in 1984. Indeed, Paik had remained a little-known figure in his home country until then. For that reason, his 〈Good Morning, Mr. Orwell〉 came as a shock not only to artists in Korea and cultural figures but also to its general public when it was aired via satellite on the KBS network in 1984. To Korean viewers who were gradually adapting to the color television that had been introduced in 1982, it was a wondrous experience with its dazzling images incorporating state-of-the-art technology and works by world-leading artists that were presented in the broadcast. This would lead to other “satellite broadcast art shows” such as 〈Bye Bye Kipling〉 (1986) and 〈Wrap around the World〉 (1988); with the installation of his masterwork 〈The More the Better〉 (1988) in the central hall of MMCA Gwacheon, he became known as one of Korea’s preeminent artists.

Examining the content of 〈Good Morning, Mr. Orwell〉, however, one could describe it as a satellite version of 〈Global Groove〉 in terms of its portrayal of a “global village” ideal or its allusions to communication among different cultures. 〈The More the Better〉 also reflected an awareness of Vladimir Tatlin’s 〈Monument to the Third International〉—and if one considers that Tatlin’s idea was a symbol of a social utopia, both as a revolutionary Russian response to Paris’s Eiffel Tower and a massive media monument for newspaper, television, and radio purposes, the works of Nam June Paik served as exhibitions of new civilization based on video and global networking. Satellite art shows such as 〈Good Morning, Mr. Orwell〉 were no different in this regard.

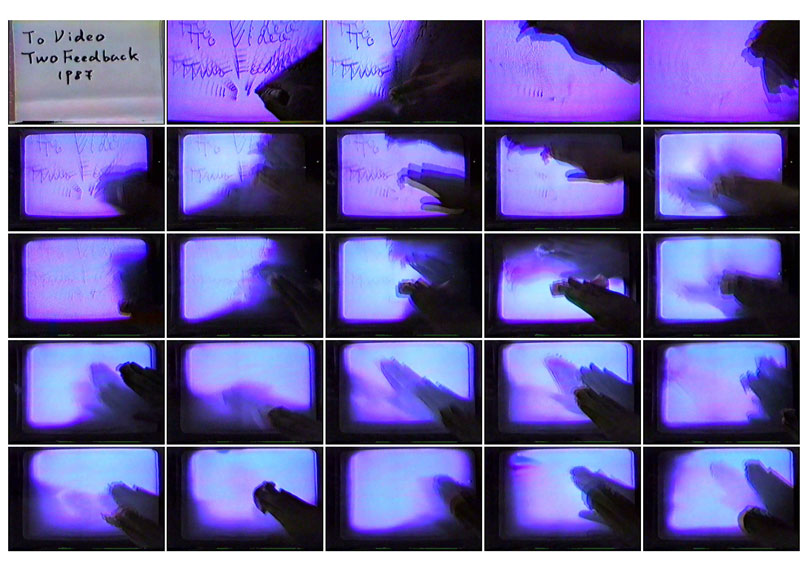

Yi Won-Kon, 〈To Video Two Feedback〉, single-channel video, 3 min. 59 sec., 1987_Upon seeing Nam June Paik’s 〈Good Morning, Mr. Orwell〉, Yi Won-Kon discovered the potential of the video medium and began studying on his own to master the mechanisms of video devices. The work captures a kind of audio feedback phenomenon that occurs in the process of text being written and then erased from the monitor’s screen. A sense of rhythm is then created through repeated re-filming and re-showing as video scenes are played back and the movements of the hand in the image are imitated by an actual hand. Image Provided by Art In Culture

Up until this time, Korea could be seen as not having yet achieved a sufficient opening of its cognitive horizons to adopt new media such as television and video as means of achieving “new art.” With this work, however, Korean society was able to gain a clearer understanding of the potential of video art, which would lead to the emergence of experimental works by many young Korean artists. In my case, I decided after seeing 〈Good Morning, Mr. Orwell〉 that I should actively study video and computer technology; I went on to present my first installation work incorporation television monitors and radio at the 《Indépendents》 exhibition in 1986, and I become a video artist convert with exhibitions such as 《Yi Won-Kon Video Installation》 (Su Gallery, 1987). Shin Jin-sik took note of the possibilities of the computer as an artistic medium, presenting his “computer prints” beginning with a solo exhibition in 1985; in 1987, he would direct the staging of a group exhibition titled 〈Korea’s Computer Printmakers〉. Many others would begin working as media artists more or less around the same time, including Kang Ik-joong, who began actively incorporating computer panels, bicycle wheels, and other mechanical elements from his 《EXODUS》(1986) exhibition onward; Kim Yun, who made active use of broadcasting equipment while employed at the KBS network; Kim Jae-kwon, who presented a display of lasers and artificial light at a 1988 “laser show” in the skies over Seoul’s Yeouido neighborhood upon his return from studying in France; Cho Tae-byung, who studied in Japan before returning to produce various experimental design works; Seo Dong-hwa, who began producing kinetic works again around 1987 and staged performances in the 1990s that involved piloting an aircraft he had produced himself; as well as Yook Keun-byung, Kim Hae Min, Seong Sun-ok, Oh Kyung-Hwa, Ha Yong-sok, Lee Kang-hee, and others.

By the 1980s, the stature of video art was comparable to that of experimental film in terms of its use of new media and experimental images; at the time, it can be spoken of in comparison to avant-garde art, which used video as an art object or a means of recording. In other words, whereas experimental film had carried on from photography as a forum for experimentation with moving image aesthetics, with experimental filming of the frame, mise-en-scène, and editing representing the chief interests in a tradition of photography and cinema dating back more than a century, the norm in avant-garde art was to use video images as a recording medium or another new means of artistic experimentation.

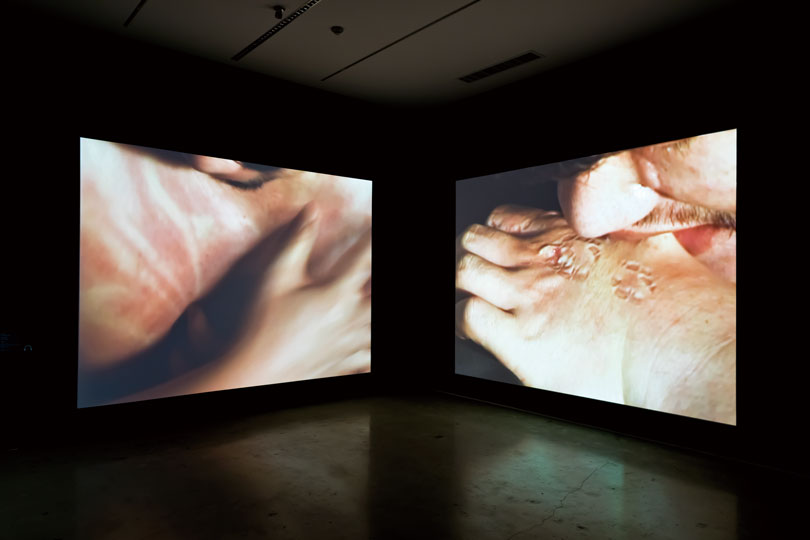

Oh Sang-ghil, 〈Torn Flesh〉, single-channel video, 2 min. 28 sec., 1999 (L); 〈Skin Licks〉, single-channel video, 4 min. 7 sec., 1999 (R)_In both works, images of harsh and violent acts against the body are captured by a camera with a fixed perspective. Acts of scratching skin with the fingernails until it turns red or biting hard enough to leave heavy teeth marks are repeated over and over. They are seen as new attempts to apply the video grammar of early avant-garde video to the area of video art, subverting the refined beauty of frequently repeated images in films and advertisements while seeking a new aesthetic adopting video as its principal medium. Image Provided by Art In Culture

(Re)Inventing New Media

By the 1990s, however, the world’s attention was focused on the new artistic possibilities represented by new media. Much of this had to do with the media environment at the time transitioning into a multimedia/digital era, as well as increased societal interest in the film industry amid early video industry encouragement efforts after the South Korean government proclaimed a new strategy for “video industry promotion” in 1993. In terms of artists, the media artist association, ’Art Tec Group’(Kim Jae-Kwon, Shim Young Churl, Kim Young Jin, Kang Sang-joong, Song Joo-Han, Kim Yoon, Lee Kang-hee, Shin Jin-sik, Gong Byung-yeon, Cho Tae-byung, and Park Hyun-ki) was formed, and the latest works from overseas were being presented in earnest through exhibitions such as

《UMWANDLUNGEN》 (MMCA, 1992), which had Kang Sang-joong, Lee Yun, Kim Jae-Kwon, Park Hyun-ki, Shin Min-gyu, Shin Jin-sik, Shim Young Churl, Yook Keun-byung, Oh Kyung-hwa, Lee Kang-hee, and Cho Tae-byung as participating artists. Additionally, large-scale exhibition such as 《Art and Technology》, 《The Garden of Imaginative Tales》, and 《Science+Art》 were being held; in particular, the activities of world-renowned artists were shared through the 《Information Art》 exhibition designed by Nam June Paik for the inaugural Gwangju Biennale in 1995.

Internationally, the term “video” was falling out of use; it was only in Korea that the term “video art” represented the dominant trend during this time. (For example, “video art” was first used as an 『ART INDEX』 topic index term in 1971, but would be replaced with “media art” from 1989 onward.) In other words, while the 1990s represented the greatest period of expansion for video art, the analog era was coming to a close, and as digitally produced works began to proliferate, the trend was one where a growing number of works were being produced and screened in multimedia environments. For many Korean artists, however, analog editing remained the mainstream as a means of producing work, as exemplified by many artists such as Oh Sang-ghil who were inheritors to the experimental film spirit. This period saw the emergence of numerous idiosyncratic single-channel video works that made use of video or digital technology including Oh Kyung-hwa’s 〈Sky, Ground, People〉 (1990), Kim Jihyun’s 〈Home Shopping〉 (2000), Lee Yongbaek’s 〈Vaporized Things (Post-IMF)〉 (1999–2000), Shim Cheol-Woong’s 〈Illusion of Polygon Head〉 (1996), Park Hwa Young’s 〈Jaywalker〉 (1998), Kim Sejin’s 〈Reverse〉 (1998), Park Hyehsung’s 〈Golconda〉 (2000), and RYU Biho’s 〈Black Scud〉.

What I wish to note in particular here are, as mentioned before, the works in which artists appropriated or “hacked” media into their own means of producing new structures. Among the media widely adopted in a given era, there are typical or “safe” usage methods that exist in the most finely honed state. For example, the 1,000 or so televisions used in 〈The More the Better〉 were not designed to be used in such a close arrangement or to be positioned facing up. Had such a use been envisioned, the radiator panels inside the sets would have been positioned or shaped differently. In many cases, however, media artists have “hacked” such media or otherwise used them for a different purpose from the one that they were originally designed for.

To consider installation works first, examples such as Nah Junki’s 〈Rendez-Vous〉 (1992), Ahn Soo-Jin’s 〈Feedback〉 (1999), Moon Joo’s 〈Sea of Time〉 (1999), or Oliver Griem’s 〈Pundang Loop〉 (1997) use devices to control encounters between image and reality, thereby substantially broadening the possibilities of video art. Installation works that structured reality and imaginary within a new perceptual framework—as attempted earlier by Park Hyun-ki—were achieved through different devices and installations. Pieces such as Kim Hae-min’s 〈TV Hammer〉 (1992) or Yook Tae-jin’s 〈Ghost Furniture〉 (1995) could be characterized as adopting the same kind of framework as the aforementioned examples while also inventing new media with their mechanized interoperation; their individuality and expressive independence as media art are accordingly robust. Another form involves the redesign or reassembly of media devices for appropriation as new image apparatus, although examples of this were not commonly seen in Korea through the 1990s. For example, Kong Sung-hun’s 〈The Fall〉 (1996) was produced with 12 slide projectors made by the artist himself; while multi-side projection technology has been so thoroughly marginalized within the history of visual media development that it could well be approached today within the field of “media archaeology,” the artist made outstanding use of it at the time to produce distinctive work. Kim Young Jin’s 〈Fluids: A Transparent Shadow of Loss〉 (1995–2008) is a real-time projection using a projector devised by the artist based on ongoing research; in addition to being a superior example of a device, it also exhibits outstanding artistic mise-en-scène capabilities.

Kim Young Jin, 〈Fluids: A Transparent Shadow of Loss〉, slide projection/water droplet supply device/timer, 110 ×60 ×190 cm, 1995/2008_Combined with a video device developed and produced by the artist himself, this work shows water droplets in real time as they move irregularly with the back-and-forth movements of a wiper over a surface. Drifting with the droplets’ motions, the viewer’s gaze is a metaphorical representation of power and its repeated cycles of shifting alignments. Image Provided by Art In Culture

Kong Sung-hun, 〈Flight〉, handmade slide projector_One of the forms of Korean video art during the 1990s involves the redesign and reassembly of previously produced media devices to use as new image apparatuses. Kong Sung-hun, who had re-enrolled in an engineering college after previously majoring in painting, devised his own form of image processing known as “multi-slide projection,” using a slide projector that he had developed independently. The method involved multiple projects showing slides with segmented images of a body at fast speeds. Image Provided by Art In Culture.

Kong Sung-hun’s multi-slide projection and Kim Young Jin’s real-time projection remain quite rare examples, but the late 1990s were a period when beam projectors began to be appropriated as artists’ tools amid improvements in their performance and cost-effectiveness. Unquestionably, the new trend that began around this time was one where ways in which media art was exhibited underwent a major transformation as video beam projectors entered the gallery, having then undergone performance improvements and entered into widespread use. In 1997, Park Hyun-ki began presenting works such as 〈Mandala〉 and 〈Pagoda of No Shadow〉, which involved projecting images onto the floor or objects on the floor from the gallery ceiling. Kim Chang-kyum achieved an “intricate coordination between object and image” through video images projected onto real objects. In his installation works, which continued on with the 〈Water Shadow〉 series, he achieved an “exquisitely sutured reality, like an object wearing a video skin” in the imaginary and space, leading viewers to lose their way between what is real and false. The artist draws us into the spaces of this “meeting,” guiding us to read into its fissures and differences, but what the viewer is actually encountering is the different versions of synthesized reality evoked by the juxtaposition of the real and imaginary. This may be seen as echoing the staging and context of Park Hyun-ki’s 〈Pagoda of No Shadow〉. The work of Ku Ja-young originated in his previous attempts to blur the boundaries between “real and imaginary” or “existence and illusion.” His 〈Window〉 series (1998) causes viewers to lose their way in a labyrinth of real and false images image created, as if by magic, by layers of overlapping video images of objects repeatedly projected onto the actual objects. As a result, their consciousness is drawn into a third space, or “interspace.”

The city of Seoul began full-scale planning of its Media Art Festival in 1999, and the inaugural Media Art Biennale(2000) was held the following year. Since then, a total of seven events have been held, and it has established itself as a large-scale global media art exhibition. At the non-governmental level, Art Center Nabi was opened in 1999 as a specialized media art institution, which had operated on an ongoing basis since then as an international media art hub. The culture and arts yearbook published by the Korea Culture & Arts Foundation in 2000 was the first to treat media art as a mainstream art genre, it having previously been regarded as a trend in experimental as opposed to mainstream art. Around the same time, the term “video art” became used less and less frequently in Korea as well.

Imagining the Unseen

As seen above, Korea video art confirmed its own cultural identity while sustaining a minor current amid an impoverished surrounding environment; experienced a historical “baptism” through new media and information technology; and grew and expanded through its encounter through a curious twist of fate in the form of Nam June Paik. With the exception of Paik, almost all of the artists who perceived video itself as a means of artistic expression and pursued their own independent aesthetic had come from art colleges, and in that sense early Korean video art may be seen as having been adopted and developed within a context of expanding the arts. At the same time, the media art from the 1990s onward included more and more representation by specialists in fields outside of the arts, including film, music, theater, and the humanities—a trend that would become even more pronounced in the 2000s, leading to more clearly defined developments in interdisciplinary interactions involving technology, science, philosophy, and other areas. Yet it is very much worth noting that this kind of convergence and consilience is ultimately made easier—or possible at all—when “visualization” is understood as the medium. As I mentioned at the beginning of this piece, I believe that the visualization of all phenomena that exist unseen or that are believed or imagined to exist forms the foundation not only for the visual arts but for all human intellectual activities—and I see that as suggesting that the same exploratory passion seen in video art should be carried on in new fields.