This month, TheArtro presents a special feature series titled “How to Win Global Art Market,” that is essential for Korean Contemporary Art’s competitive stake in the Global Art Market. The series, starting with an article by the curator Daehyung Lee, interviews leading journalists, art consultants and art market and marketing specialists from around the world. Discussions on global art marketing trends and strategies over the past ten years are coupled with expert inputs on institutional support to strengthen the international competitiveness of Korean Contemporary Art. Experts interviewed include Carsten Recksik, the publisher of art magazine ArtReview and ArtReview Asia, Jane Morris, Editor-at-Large of The Art Newspaper, Partner of Futurecity, Sherry Dobbin and Louise Hamlin, founder of Art Market Minds, which is a leading platform for art business conferences. In addition, James Green, Director of theDavid Zwirner, Jagdip Jagpal, Director of India Art Fair, David Field, Freelance cultural communications consultant, and Jesse Ringham, Head of Content at the Serpentine Galleries also accepted our requests for interviews. These privileged insights from the insiders of the global art market surely deserve our undivided attention as Korean art sets sights on broader horizons.

Jane Morris is an editorial consultant at Cultureshock Media and editor-at-large of The Art Newspaper

Q : In the last 10 years, what major changes have there been in global marketing strategies? What kind of roles are being shared and collaborated in global and local media?

Jane Morris :

The art world

The international art world (or art worlds) is made up of a complicated network of people (artists, curators, gallerists, collectors, critics and so on) and institutions (museums, biennales, art fairs, auction houses, commercial galleries and so on). There is a relatively small, truly “global” network of people (curators such as Hans Ulrich Obrist, collectors such as Francois Pinault, gallerists such asIwan Wirth) and institutions (such as theMuseum of Modern Art in New York, Art Basel, the Venice Biennale), as well as regional and national networks, involving a similar cast of actors, but playing on more local stages.

In the past 10 years, despite the financial crash and populist counter-tendencies, we have witnessed increasing internationalisation of the art world and art market. This is especially true in terms of increased appreciation of art and artists originating outside North America and Western Europe, or from art originating from diaspora artists (for example Latinx and African American artists). We continue to see the emergence of new contemporary art museums, art fairs, galleries and other art world events/institutions around the world.

But — another feature of globalisation — we are also seeing an increase in overall power of an increasingly small group of “winners,” whether that is commercial galleries (Gagosian, Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth), cities (New York, London, maybe Shanghai), museums (MoMA, Tate, Pompidou), art fairs (Art Basel, Frieze), biennales (Venice, Documenta). It means that it is difficult for both new entrants and many established small-to-mid-scale – even high end - players to cut through the noise and capture attention, especially at the most international levels.

It means that any new initiatives might want to start by:

• Mapping the international art world and looking for potential collaborators: art fairs (special themed sections, for example at the Armory, Frieze etc), museums (especially those with established or interest in diversifying scholarship and art history like C-MAP at MoMA, curators who have shown an interest in more diverse programming such as Mami Kataoka and Stephanie Rosenthal), media collaborations and so on.

• Mapping the regional art world and looking for similar collaborations, and opportunities for synergy in Asia.

• Maximising any existing national opportunities (for example, the international interest in the Gwangju Biennale or major exhibitions such as 2019’s “Awakenings” – it would be great to see a version of that at a major Western museum) to activate a wide network of Korean museums, not-for-profits, artists, galleries and curators.

• Find or create platforms to promote diversity, sophistication and depth of Korean art, art history and history.

In short: collaborate to amplify interest and provide context.

《Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s》 at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea in 2019. Image Provided by MMCA

The arts media

Extensive essays have been written about the deep challenges facing the independent media (see https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/28/does-journalism-have-a-future) and the art world has not been immune, see my article (https://www.artagencypartners.com/whither-criticism/).

For the purpose of this questionnaire: the “traditional” independent media (whether print or online) has the benefit of existing, engaged and knowledgeable readerships, and is generally perceived as trustworthy and authentic. As a result, it remains important to engage with it, even though it is no longer as dominant as previously. Obviously, the greatest change in the past ten years is the opportunity for individuals and institutions to communicate directly on their own channels, online and via social media.

Q : We are experiencing a rapid change in platform from offline public relations to digital and mobile marketing. How are digital strategies changing, and how do you see its future?

JM : Traditional PR (one-to-one relationships; opportunities to meet artists, expert gallerists and curators; press trips to major museums, fairs and biennales and so on) remain important, particularly in bringing less well known territories or art stories to attention (see, for examples, campaigns and coverage in titles such as the New York Times, Financial Times, Economist, The Art Newspaper and Artnet, around the opening of the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, the contemporary art scene in Ghana and also the support and coverage for the 1:54 art fairs devoted to African art, the emphasis generated around Brazilian art thanks to informal collaborations a few years ago between the Sao Paulo Bienal, Inhotim and Latitude1) , (http://www.latitudebrasil.org/).

Nevertheless, perhaps the biggest shift in the media landscape has been the opportunities presented by digital for museums, galleries, art fairs, auction houses and other “brands” to become content producers in their own right, communicating directly with their own audiences. Some (the Tate, V&A, Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Art Basel, Gagosian and so on) have even entered the magazine world, producing print and digital content, sophisticated email newsletters, marketed via social media (which can be valuable content in its own right). These businesses are often creating content that is as apparently “independent,” authoritative and engaging as the truly independent media, and have brought in professional journalists, editors and film-makers to produce their content.

Having said that it is challenging to produce editorial that is perceived as valuable, convincing and authentic to a sophisticated, art readership, so it is likely that arts business will continue with a mix of traditional PR/relationships with the independent media, their own content creation – although the balance of the mix may continue to evolve.

Q : What are your thoughts on the impact of technological development (ex. Big data, A.I., etc.) to art market?

JM : The impact of technology in the art world remains a widely discussed, contentious and often misunderstood subject.

The online selling of art has proceeded much more slowly than many people expected: this is possibly a reflection of the high value of many works of art, the priority both sellers and buyers place on the physical experience of the work and the desire of galleries to sell in a one-to-one environment (and “screen” potential buyers of the most desirable works by their artists. The art market is, at the higher end, a “matching” market, not a “retail” market). Most works of art on Artsy, and especially those sold by the most reputable galleries (for example, the galleries that attend Frieze or Art Basel) do not carry prices, and direct potential buyers to the art gallery in question. Online viewing rooms further cement the gallery’s grip on the one-to-one relationship

and control over the way prices are displayed. Nevertheless, some commentators argue – convincingly – that at the lower end of the market (up to £10,000) sales of works of art may eventually largely move online.

In terms of big data, AI, blockchain and the like. The chief problem here is that auction houses, galleries and many owners of art works are extremely unwilling to share the data sets that would be needed to make a Netflix-style “recommendations” system, for example, for works of art. The same is true of the kind of information that would assure provenance and authenticity (in the UK, Land Registry and car registration at the DVLA all existed and operated successfully before blockchain because the buyers and sellers of property and cars were both obliged legally to register information and saw the relevance of such an activity). Of course, it is possible that ingrained art world behaviour (price secrecy, ownership secrecy, client secrecy) might be forced to change if new generations of buyers insist on it, or if arts businesses see a benefit in contributing to a sort of “black box” of anonymized data (they do not want to pass control to new tech businesses and platforms). But it may be that, especially at the top end, new buyers enjoy being part of an exclusive “club” as much as their predecessors.

Q : There has been a long history of academic research to strengthen global competitiveness of Korean contemporary art. There is an absolute shortage of publications, journals and channels in English. What policy and institutional support do you think are required for the Korean government to overcome this?

JM : It is hard to overstate the importance of exhibitions, especially major survey exhibitions in international museums (or with texts, audio guides catalogues etc. in English), and English-language publishing, from scholarly research, to exhibitions catalogues and English-language arts news and criticism created and developed in Asia.

As an example. The Italian art scene from around 1945 to 1970 is now considered deeply significant, but for decades it was overshadowed by American, and later German, art history. Part of the difficulty, according to contemporary Italian scholars such as Luca Massimo Barbero, is that texts were very rarely published in English — despite the fact that Italy has long enjoyed committed collectors, established galleries and admired museums. It has taken a concerted effort from curators such as Germano Celant (with exhibitions in New York in the 1990s onwards), Barbero and a new generation including Massimiliano Gioni, art dealers and advisers including Luxembourg and Dayan and Allan Schwartzman, to put postwar Italian art on the international map. It is worth noting that for many in New York, the 2019 exhibition of Lucio Fontana at the Met Breuer was considered a “revelation.”

Much of the same set of circumstances appears to apply to Korea.

Useful steps would include:

• A central digital resource, with information on art, artists, curators, museums, galleries, as well art history and its connection to the political, social and philosophical history of Korea and the region.

• An English-language translation, editing and publishing programme of existing and new materials

• Development of accessible platform for discussion and discovery of art in Asia, in English

• Connection to major research programmes in other museums and forums (MoMA, Tate, Pompidou, international curators’ associations, to mount shows and publish catalogues)

• Connection to major English language arts publishers such as The Art Newspaper, Artnet etc. – including a budget for press trips/meet the experts trips tied to on-diary moments (Gwangju Biennale, Korean Pavilion at Venice etc.).

KIAF ART SEOUL 2019. Image provided by Gallery Association of Korea

Q : Art fairs are overflowing, from affordable art fairs with limited price ranges to photo-centric fairs. Nevertheless, various attempts are being made to create a new kind of art market. What kind of art fairs do you think Korea needs?

JM : The number of art fairs varies, but at The Art Newspaper we list between 280 and 300 a year likely to be of interest to an international readership: the number grew dramatically between 2000 and now, where there has been some evidence of retrenchment. For much of the past decade, the argument was that — to stand out — fairs needed to be “the best” (dominant brands such as Art Basel, Frieze) or a clearly defined, niche proposition (1:54, Independent, Miart and so on). This appears overly simplistic now, because — as Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baia Curioni pointed out in “Cosmopolitan Canvases: the Globalisation of markets for contemporary art” — the art market is often much more local or regional than many realise. This almost certainly explains the rise of sustainable arts centres in cities including Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai and Taipei, and there is no reason why Seoul, with its artists, museums and collectors, could not have a viable art fair.

To attract international visitors, it would make sense, however to:

• Find a date in the international calendar that can become “the week to travel to Seoul”

• Make partnerships with non-commercial institutions (museums, biennales) as well as commercial galleries to create a week-long “event” (museum openings, talks and lectures, collector visits etc. — Frieze in London was hugely successful at this in its launch period 2003 to 2007)

• Make sure the art fair is surrounded by cultural offerings, including talks and lectures on the artists, art and art history of the region, studio visits

• Tap into art world interest in Korean fashion and food, as well as artists

Q : How much are you familiar with Korean art history? Which Korean artists do you know, and from what route and point in time were you able to find out about them?

JM : My knowledge of Korean art history is partial and decontextualized: I have never visited Korea, written any longer form articles about its art and artists, or studied Korean art as part of a wider art history course. What I know has come about accidentally through museum exhibitions, commercial gallery shows and the inclusion of artists at biennales, such as the Venice Biennale, Documenta and art fairs (Art Basel Miami Beach, Frieze Masters) in the west.

The artists I am aware of include: Nam June Paik, Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, Lee Bul, Do Ho Suh, Jeongmoon Choi, Haegue Yang, Michael Joo, Kimsooja, Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho.

Nam June Paik was (no doubt still is) taught as a core part of art history at the Courtauld and University of the Arts London, at least as far back as the late 1980s, where he is treated as the pioneer of media/digital art and as a collaborator with Joseph Beuys (who, alongside Duchamp, remains an obsession of western art schools). His reputation and recognition has been cemented (in London eyes) through major exhibitions such as Electronic Superhighway (Whitechapel Gallery, 2016) and a survey at Tate Modern last year.

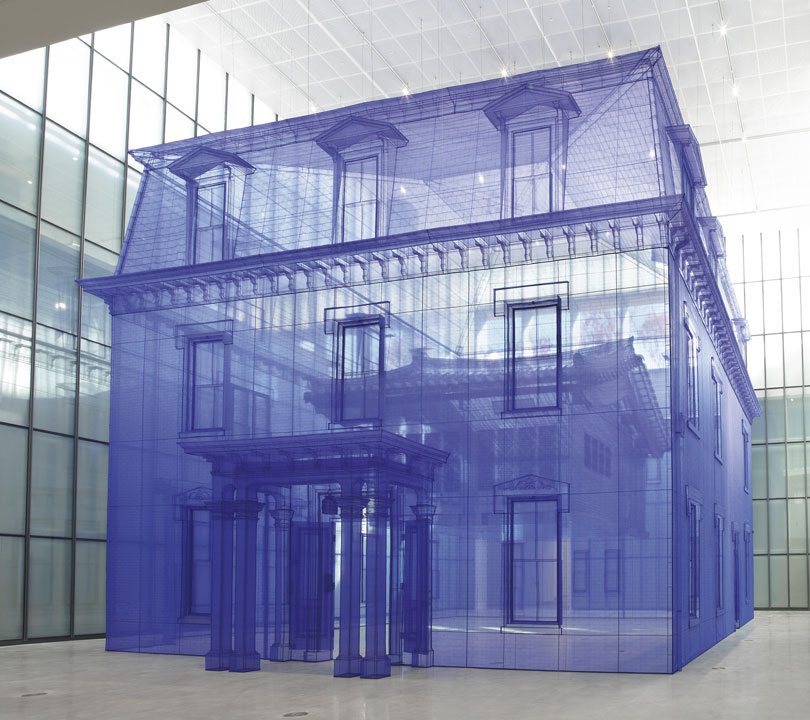

DO HO SUH 〈Home within Home within Home within Home within Home〉, 2013, Installation view, Home Within Home, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea, 2013–2014 © Do Ho Suh. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

All the other artists have shown exhibitions in commercial galleries (for example, Do Ho Suh in Sadie Coles’ “Room,” Lee Ufan with Lisson Gallery and Alexander Gray), art fairs and in museum exhibitions in London, New York and Germany. Lee Ufan led to awareness of the 1970s Korean minimalists/monochrome group, which museums have associated with Mono-Ha and Zero, and which was heavily promoted in the market (partly by Allan Schwartzman of AAP) around 2014. In 2016, I was part of a small study group in Mexico which included Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho where we discussed digital and dematerialised art (having previously seen their work in Venice).

Generally, my ignorance is my problem. But there are some occasions where information proved hard to get: in 2018/19 I was very eager to cover the Awakenings, Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s show, but found it very hard to get texts, interviews etc. from the museums in Japan and Seoul – subsequent efforts to get a catalogue also failed (Waterstones’ lists it as “publication cancelled”). This appeared to be a landmark show and the opportunity to promote it heavily to an international audience was possibly not maximized. “Breakthrough” exhibitions that change art history are incredibly important, as are accompanying catalogues: Magiciens de la Terre, Documenta 11, Cities on the Move, Wack!, Outliers and the American Vanguard and so on.

Q : What role do you think your current work plays in terms of the overall art ecosystem? And with what areas do you find collaboration important?

JM : Independent publishing, broadcasting and other forms of media retain an important role in the discovery, understanding and validation (or otherwise) of art, artists and art movements, as well as providing insight into the way the art world works. Art is often discussed in difficult or coded language (especially by curators, academics and specialist publications), while the art world itself is fragmented and confusing.

It is the role of the independent media to entertain, explain and educate: at our best we are an important mediator and explainer within the art world and between it and broader, art interested-audiences. Good quality journalism and media communicates with knowledge, authority, authenticity and trustworthiness, as well as being interesting, accessible and engaging.

Collaboration is vital. The media relies on access and good relationships with artists, curators, museum directors, gallerists, auction houses and so on. As it has been weakened – mostly by the challenges of the internet and social media revolutions, particularly the disappearance of its advertising base to the social media channels and Google — it relies even more on collaboration in terms of commercial partnerships and sponsorships, and also press trips, help and support from PR and media professionals to access information, images, filming opportunities and so on. The media is an integral part of the art ecosystem and remains an important place for the discovery and understanding of art and art-related issues.

Q : Various programs for securing new collectors are evolving in different ways. What aspects of Korean contemporary art should be strengthened in order to appeal to global collectors? What has changed in the criteria for collectors that they find most important?

JM : Collectors have different and complicated motivations — to take part in an exciting intellectual journey; even quasi-spiritual engagement/fulfilment; visual or haptic attraction/appeal and satisfaction; being part of a “club” of like-minded individuals, meeting new people (especially artists); home decoration and/or social status; investment and so on. Almost all of them want and need validation that the works they are buying are important critically and at least sound financially, the most philanthropic collectors or least expensive works of art aside. Validation is made (as described above in question one) by the art and works in question being seen as part of and valued by art world networks, whether local, regional or international. That generally means the art needs to be talked about by the right critics and curators, included in the right museums shows and collections, seen in biennales and sold by the right galleries at the right art fairs.

• Platforms for the discovery of Korean art and artists are crucial

• So is providing accessible, contextual information

• Supporting more Korean galleries to attend international art fairs (the main gallery I’m aware of is Kukje) – this has often been done by governments to promote their artists and galleries — as well as support for artists to show abroad in exhibitions and biennales

• Consider generally the issues of validation, knowledge, trust

There is much discussion at the moment about ways of growing the collector base, particularly among a younger demographic (younger Gen X and Millennials) – see Talking Galleries, Art Basel Conversations and so on. It is very unclear how different this group is really from their older counterparts: given its price points, contemporary art remains for most people, expensive and out of reach. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that younger collectors expect: information easily available online, price and value transparency, clear language, a more welcoming, less elitist atmosphere in galleries and museums, a better experience and customer service.

1)The Art Newspaper (Sept 2014/2013) : https://cultureshockmedia.co.uk/work/

Financial Times :

Art Basel Miami Beach highlights wealth of Latin American talent

São Paulo: art on the rise

Financial Times Magazine (sponsored supplements) :

2013: http://latitudebrasil.org/media/uploads/clipping/clipping/2013_10_11-ft-w.pdf

2014: http://latitudebrasil.org/media/uploads/clipping/clipping/2014_03_28-ft_1.pdf

Telegraph :

http://latitudebrasil.org/media/uploads/clipping/clipping/2016_03_15-the.pdf

Art Review :

http://latitudebrasil.org/media/uploads/clipping/clipping/2013_09_01-artr.pdf

The Art Newspaper :

http://latitudebrasil.org/media/uploads/clipping/clipping/2013_09_01-thea.pdf

Related Articles

How to Win Global Art Market by Daehyung Lee

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with Carsten Recksik

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with Sherry Dobbin

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with Louise Hamlin

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with Louise Hamlin

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with James Green

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with Jagdip Jagpal

How to Win Global Art Market - An Interview with David Field

How to Win Global Art Market – An Interview with Jess Ringham

Jane Morris

Jane Morris is an editorial consultant at Cultureshock Media and editor-at-large of The Art Newspaper, and has contributed to titles including Tortoise, the Economist, Monocle and Art Agency Partners on art and culture. She was the editor of The Art Newspaper (London and New York teams) for almost a decade. She was previously head of publications at the Museums Association, and a judge of the European Museum of the Year Award. She has contributed to Radio 3, Radio 4 and Monocle 24 radio, and has written for national newspapers including The Guardian and The Independent. She studied fine art at Central St Martin’s College of Art and Design, and journalism at City University, London. She is an editorial board member of Tate Etc, the world’s biggest circulation art magazine.