Features / Focus

Preview of Busan Biennale 2020 : Conversation with Artistic Director (part. 1)

posted 03 Sep 2020

No one could argue that the year 2020 has been unpredictable. Many plans have been delayed and canceled in all over the world. Like biennale, a large-scale event held once every two years that people from various countries around the world have to work together for a long time, has had to be faced with a new trouble due to limitation of travel in this pandemic period. The Busan Biennale 2020, which has been preparing while overcoming difficulties that can’t be mentioned one by one, is set to open.

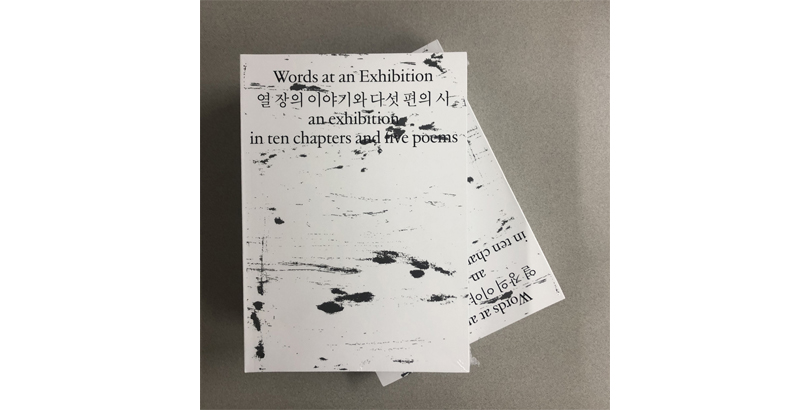

The Busan Biennale 2020, organized by Danish artistic director Jacob Fabricius, opens under the epic title "Words at an Exhibition - an exhibition in ten chapters and five poems” Although the Biennale is a comprehensive art venue that freely cooperates with other genres based on visual arts, this year Busan Biennale in particular, visual arts, literature and music interacts more harmoniously with each other than ever before as the axis of exhibition.

TheArtro present a conversation, as a preview of the Busan Biennale 2020, between the artistic director Jacob Fabricius, the Biennale curatorial advisor KIM Sung woo, and the exhibition team leader SeolHui Lee. With KIM Sung woo's hosting, there were interesting talks on exhibition methodology of the director Jacob Fabricius and his perspective on the locality of Busan and the contemporary nature of the biennale of this era. Hopefully, readers who cannot physically come to Busan could learn more about the Busan Biennale through this preview.

Busan Biennale 2020 ; Words at an Exhibition- an exhibition in ten chapters and five poems

- Jacob Fabricius/Busan Biennale 2020 Artistic Director

Busan Biennale 2020 Artistic Director, Jacob Fabricius, is currently the Artistic Director at Kunsthal Aarhus, Denmark. Fabricius previously served as Director at Malmö Konsthall, Sweden (2008–2012), and as Director at Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen, Denmark (2013–2014). He has curated numerous of international exhibitions most recently he curated 《iwillmedievalfutureyou1》 at Art Sonje Center (2019). Fabricius is the founder of the publishing company Pork Salad Press and the newspaper project Old News.

- KIM, Sung woo/2020 Busan Biennale 2020 Curatorial Advisor

KIM Sung woo is a curator and writer, who is interested in ways of producing questions/ questionnaires via curatorial methodologies in contemporary art. KIM directed the curatorial project/ exhibition and management of Amado Art Space, not-for-profit alternative space in Seoul (2015-2019), and was appointed as an artistic director in the form of curatorial collective for the Gwangju Biennale in 2018.

- SeolHui Lee/ Head of the exhibition team for Busan Biennale 2020

Seolhui Lee is the head of the exhibition team for Busan Biennale 2020. She has a master’s degree in Art History and was selected for both the 7th Gwangju Biennale International Curator Course (2016) and Tate Modern Intensive Program (2020). Seolhui has worked for the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) and Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA). Currently, she also works as an adjunct professor at Korea National University of Arts. Her essays have been published in 『Korean Contemporary Art since 1990』 (2017) and 『Reading Korean Contemporary Art with Keywords』 (2019)

Image Courtesy of Busan Biennale

KIM : I would like to look into the Biennale and the curatorial of the artistic director of the 2020 Busan Biennale, Jacob Fabricius, and talk about his previous major curating experiences in connection with this. Then I would like to ask his view on the limitations or alternatives in curating generated by COVID-19 and listen to the artistic director’s thoughts on the contemporaneity the Biennale is faced with.

I would like to start this conversation with the structure of the Busan Biennale 2020. This edition of the Busan Biennale seems to take quite an interesting curatorial approach. For instance, rather than using one solid keyword to explain an exhibition, this Biennale creates a structure to explore various routes to access the Busan as a city, its locality, history, modernization, and individual life in it by inviting 11 authors to write short stories and poems and then matching the writings with the works of participating artists. In other words, the Biennale takes an approach similar to ‘rewriting history’ without drawing the stories about the city created by mainstream media; interpreting the city through microhistory rather than from the perspective of official history. Such an approach awakens new perspectives toward today by addressing different generations, genders, and figures based on the stories captured in different genres, as well as viewpoints from literature such as sci-fi, history, thriller, noir, and crime novels, and not replicating one-sided and fixed scenes of the day as described through the media. I would like to hear more about this edition of the Busan Biennale based on your curatorial methodology/ approach.

FABRICIUS : Yes. basically that’s correct. I have approached the exhibition in the complete opposite way than how I would usually curate and make an exhibition. This time I have been inviting the authors first, changing the situation where usually authors are invited at the end of an exhibition so they could write about the artists for the catalogue. But here I have flipped the situation so authors would start and produce texts as the base. You can say they are the skeleton, if you consider the exhibition as a whole body. The musicians and all the artists are organs, muscles and tissues. So if you see it as an organism, that would be my picture or interpretation of this exhibitions methodology. And of course by selecting authors who represent different genres, you have a sense of how they would write, a sense of their approach, and outcome of what the visual artists should relate to. So who has been invited as writers is not a coincidence, they represent different things. They represent their sphere, and it is meant to generate different perspectives of Busan.

In the beginning of my concept, I was working with already existing texts. That was my first idea. First of all, it was easy to control, because I knew what I would have and get, and that was something that I could relate to. I had never in my wildest imagination thought that it was possible within a year to actually commission 11 different writers, have the writers come to the Busan, think of a fiction, narrative, story, and actually execute it, and transcribe it, everything. That was beyond my imagination. So it has developed, at around this time last year, when it was my first time in Busan after I had been selected as artistic director. So a year ago, I changed my concept from using the existing stories and books to being new scripts.

I was of course researching Korean literature because I wanted to have a majority of Korean writers who could understand the language, the city, the neighbors, and the history of the peninsula. So it was important that we have majority of Korean writers.

It’s not easy to get English translated short stories by Korean writers. I went to Kyobo Bookstore, they have thousands of books, but they don’t have English versions. But then in a basement close to the MMCA, I found a fantastic English bookshop. They have hundreds of titles by young Korean writers in their 20-40s, just short stories, supported by LTI (Literature Translation Institute of Korea). And because of that I could buy books and read a lot, and that helped me to get a sense of contemporary young writers in Korea.

KIM : You mentioned that the writers are like skeletons of the exhibition, and their texts are a sort of core to develop this Biennale. But there are thousands of writers in Korea. Then, the criteria for the selecting process could be very diverse like your personal taste, interest, political tendency or any others. I’d like to know the criteria that you had in selecting the writers for this exhibition.

FABRICIUS : I consider various aspects when I curate an exhibition. The process of making an exhibition is similar to putting the pieces of a big puzzle together. When I choose the authors, I tried to find the balance point while considering many different elements, such as gender, genre, age, expression, theme, and so on to fit the diverse pieces together.

I was looking for writers that had an association to Busan. I came across the writer BAK Solmay, from which nothing was translated, and I was told that she was a young writer who had written two short stories about Busan. I got her number, and sent her a text message on a Friday night. It happened that she was just coming to Busan on Saturday, So I met her right away and had coffee with her and discussed her approach.

So some of the writers like BAK Solmay I had never read, I just met them. I had good conversations with them and discussed the way they think and approach the world. Other ways were reading their short stories and trying to basically fit into the plan and this idea that I had.

I was fascinated by the local modern history museum in Busan. Because it shows the colonial history, it shows the Korean war, the arson against the American Cultural Center in 1982 and it shows the modern Korea, and the insane development of the harbor front, how the city is built into the sea. I experienced, as a foreigner, that this museum was a center of Busan and Korean history.

When I spoke to foreign writers, I told them about what fascinated me about the city, like ‘Yeongdo, the big boats, the ropes, the machinery. This fascinates me, and you should come visit and see what you find interesting,’ I would say to them.

And I was told about a young Colombian writer who wrote a detective story about Busan. That’s Andrés Felipe SOLANO. He lives in Korea and he has lived here for 8 years. The idea of having a Latin identity, Colombian identity, being half-way into the Korean system, being half-way into the different Latin tradition and style of writing – their style of writing is very different from Danish, and I’m sure it is quite different from Korean as well – was interesting and part of the big puzzle. When you do an exhibition, at least in my case, I select artists for different reasons. There’s a balance: age, gender, topics, expressions. That’s also what I wanted to find in their literature.

Structurally, I could have selected four, six or any number of writers, but I also wanted to relate to the composer, Modest Mussorgsky. That was my conceptual framework, the reference point for me. He made ten piano compositions inspired by the posthumous exhibition of Viktor Hartmann, and he made this sound intermezzos, which he called ‘promenade’. Promenade is like a walk in the park. It is like the glue that makes two compositions stick together. So there’s ten compositions and five promenades. So conceptually my aim was to have ten stories and five promenades. That was my goal. Mussorgsky’s Promenades appears even more important than the ten compositions in 〈Pictures at an Exhibition〉.

Busan Biennale 2020 had released a book, 『Words at an Exhibition - an exhibition in ten chapters and five poems』 Image Courtesy of Busan Biennale

KIM : As a curator, it is important to think how to approach the locality, what to see and how to build the context and understanding to curate an exhibition in a foreign country. And I think you can sort these points out well through the authors’ perspectives and literary methods.

When I think about the previous editions of Busan Biennale, it was more focused on international contemporary discourses – as generally believed to be what biennales are supposed to be. Even when it dealt with Busan, it was more at a superficial level, which was not enough to understand its locality or the real life. For this reason, this year’s Biennale is interesting because it is not just about the stipulated text level of Busan, but more of diverse aspects of Busan such as its history, modernization, and urbanization via the way of ‘translation’ from literature to visual art and sound work.

FABRICIUS : Basically, there are many things that are interesting about Mussorgsky and he was connected to art, writing and architecture. He was also known as alcoholic and some of the pieces and things he did, actually disappeared. So there’s not much knowledge about things, and how he wrote Pictures at an Exhibition. There are a lot of myth and uncertainties about him. It is known that he composed Pictures at an Exhibition during 6-8 weeks during the summer, but it is only possible to guess from his letters or stories from his friends.

For example, we can only assume how Mussorgsky might have felt when he composed 〈Pictures at an Exhibition〉 inspired by works of his friend, Viktor Hartmann, after his death. Although no one knows Mussorgsky actually went to Hartmann’s posthumous exhibition – it is a fact that he wrote Hartmann’s obituary.

As for the piano composition, it was Maurice Ravel that made it into a popular orchestra piece. Ravel took it from a piano piece and notations, into orchestra piece. That’s the version we know today. And there’s many linguists who have talked about translation.

So linguists talk about translations, there’s many theories about translation, and most people say it’s impossible to do perfect translation. There are so many things to put in translation; you can translate it directly or you can try to catch the emotions and then translate it.

The Russian-American Structuralism linguist Roman Jakobson coined the term ‘transmutation’, which basically is a term to describe going from one artistic expression into another, like taking the writing by William Shakespeare and making it into a cartoon. So this way of making a complete U-turn and using a different language, and that’s what Mussorgsky did.

And that’s the core of what I try to do in this exhibition. I don’t expect that the artists will use and translate the short stories one to one, that’s impossible and not even interesting. The writings are used as a source of inspiration.

KIM : Now, I’d like to talk about the exhibition venues for the Biennale. The list of the exhibition venues is quite different from any other year. From the old town of Busan and Yeongdo to the Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, it is organized almost like a book with various chapters. I wonder how you imagined this mapping of Busan for the Biennale.

FABRICIUS : I wanted to connect the Biennale to the Busan history. For instance, I see the old town, the local history museum as the historical epicenter of the city, because it is a colonial building, and part of the cultural center and the embassy of the US. It was also part of the democratization movement of the 80s, so it represents everything. So does the harbor in Busan. The first colonial settlement by the Japanese were in the harbor in 1896. That was their attempt to get to the mainland of Korea. So the harbor is vital to connect to the world and international waters.

There had been lots of discussions for selecting the exhibition places from the beginning and negotiations are inevitable in this type of process. Even it was uncertain that we could use more than a one place at that time. Over a period of three months, we slowly developed the stories, and over this period of time the only place confirmed was this place, Museum of Contemporary Art Busan. The development of the process mentally and curatorially was how to fit these stories in the city. One of the stories, Mark von Schlegell’s story, we could have rented the roof of Crown Harbor Hotel and have had his chapter there simply because the most important events takes place at that hotel. Some stories are very specific to certain locations and areas, and others are more liquid. But there’s definitely a strong sense in several stories of the feeling you get in the old town area and the harbor. KIM Un-su’s story is very much about the harbor, sailors and the atmosphere of the harbor and BAK Solmay is like the old town.

When I was here for an interview a year ago, I walked across the Yeongdo bridge and walked in the neighborhoods and got fascinated with the machinery site. It’s not a tourist site, it’s not an Instagrammable site, but I was fascinated by these places, the smells and textures.

Old town of Busan. Image Courtesy of Busan Biennale

KIM : I have noticed that you have mentioned the detective perspective when you talk about the senses that you felt while you walk around the city and find the way by yourself. And also when you talked about this exhibition, you’ve frequently mentioned the ‘detective perspective’. I’d like to hear more about detective perspective that you adopted in curating, it is like the emotional or sensuous mode generating from the experience you are requiring the public to experience the exhibition.

FABRICIUS : When you are a foreigner and you don’t know the language, you tend to be curious. I’m a curious person and sometimes you end up in the weirdest places, and sometimes if you like to walk, you go about to places you don’t expect. In the winter, it was a Sunday evening and everything was closed, and I was suffering from jet leg and I really wanted a beer. Of course, I don’t know what the bar signs mean so I entered a ladyboy bar. They told me to leave with hand signs, so it wasn’t the right place for me the correct. It just happens when you don’t know the language and the culture. So that’s also part of discovering the city.

The first time I came to Busan eight years ago, it was to see the Biennale. I had just googled ‘Busan hotel’ and I found a place by Haeundae Beach. That was what just popped up. I haven’t been to Haeundae ever since, but that was my first experience in the city and that’s completely different experience from the old town area.

KIM : I’d like to hear more about your previous projects, in connection with this Busan Biennale because you seemed to have used different places, not only focusing on just physical spatiality but also non-physical placeness and its narrative. For example, at the 《Contour 2013 - 6th Biennial of Moving Image : Leisure, Discipline, and the Punishment》 (2013), you used places like a church, a football stadium, and a prison instead of typical white cube. Beyond just using these unusual physical spaces for exhibitions, in the exhibition 《Polis Polis Potatismos》 (‘Police Police Potato Mash’ in English) you built the context of the exhibition while using a crime fiction as its background. Could you tell us more about this idea of combining the physical features of an existing space with the non-physicality of books or its story for exhibitions?

FABRICIUS : Literature interests me and a lot of artists of course use it in their research and works. It is the same with me. I’m fascinated by books and stories of fiction.I did 『Polis Polis Potatismos』 when I was working as the director at Malmö Kunsthall. When I worked there I tried to do an exhibition in public spaces every year in different formats. One of the projects in 2010 was based on two Swedish crime novelists, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. It was the 40th anniversary of their book 『Polis Polis Potatismos』 so it seemed appropriate.

They invented the character Inspector ‘Martin Beck,’ who was a police officer, and wanted to portray Swedish society from working, middle, and upper class. Until then, it was more like an Agatha Christie style of writing, dealing with the upper class killings and crime stories. Sjöwall and Wahlöö were making fun of the police and the authorities, and I liked it. I think making a political statement is important.

Each of the ten book they wrote took place in different parts and cities of Sweden, and one story happens in Malmö, where I was the director. With my staff, we bought 15 copies of 『Polis Polis Potatismos』 and I asked them to read the book and look for locations in the city, eating habits, traditions, and characters. Then we made a map of Malmö, and selected 14 locations in the city that appeared in the book and invited 14 artists to work in these places. We scattered them around the city, relating it to the social-geological situations in the city. The exhibition was only for 10 days - the length of the novel. This is a precise example of how I use different places and contextualize them into the narrative(storyline) of an exhibition.

The huge difference between the Biennale here and 《Polis Polis Potatismos》 is that it was the existing novel, I knew what I was getting into. I had everything on paper. But, in Busan it was like 11 writers with a blank sheet of paper. I didn’t give any instructions and I didn’t know what to expect. I think we got 11 very good contributions, very different, and it was a joy to read them all…. but I must admit I was at some point a little nervous and worried.

Following Article

Preview of Busan Biennale 2020 : Conversation with Artistic Director (part.2)

KIM, Sung woo

KIM Sung woo is a curator and writer, who is interested in ways of producing questions/ questionnaires via curatorial methodologies in contemporary art. KIM directed the curatorial project/ exhibition and management of Amado Art Space, not-for-profit alternative space in Seoul (2015-2019), and was appointed as an artistic director in the form of curatorial collective for the Gwangju Biennale in 2018.

The exhibitions/ projects he has curated include 《Glider》 (Gallery2, 2020), 《Anamorphose : depict but blurry, distant but vivid》 (WESS, 2020), 《Tracing, Detouring, Piercing》 (Hakgojae gallery, 2020), 〈MINUS HOURS》 (Wumin Art Center, 2019), 《Remembrance has a rear and front》 (publishing project, Hejuk Press, 2019), 《The 12th Gwangju Biennale: Imagined Borders》 (Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall, Asia Culture Center, 2018), 《Black Night, Video Night》 (d/p, 2018), 《sunday is monday, monday is Sunday》 (Space Willing n Dealing, 2018), 《Nobody’s Space》 (Amado Art Space, 2016), 《Platform. B》 (Amado Art Space, 2015), and etc.