Features / Focus

[Art in City] The City as a Remote Control "Go Straight There Without Transferring"

posted 18 Mar 2022

TheArtro has drawn up three feature articles on Korea’s rich cultural infrastructure to shed light on Korea’s changing art scene. A variety of attractive spaces, art galleries, and museums are scattered throughout Seoul and host diverse art events. Yet new exhibition venues and art projects are comparatively less known and the art content is mainly focused on the exhibitions of large-scale public or private art museums and international art events. Thus, to exemplify the growing diversity of Korea’s art scene, TheArtro presents three serialized articles under the select keywords “public art”, “space” and “artwork.” The first article, “Publict Art,” introduces public art around Korea. It covers public art projects aimed at creating cultural spaces in cities and a wide variety of public art that people can encounter in everyday life. The second article, “New Spaces,” features leading art sites in the nation’s major cities—Seoul, Busan, Daegu, and Gwangju—to highlight the many art spaces that have newly emerged or remain unknown. Finally, to shed light on diverse urban aspects, the third article, “Cities in Artworks,” examines the works of artists who explore the theme of “city.” Together, these three articles seek to promote not only the relatively unknown aspects of Korea to the world, but aim to also enhance the global recognition and understanding of the nation’s burgeoning art scene. These three articles can serve as a guide to Korea’s cultural attraction for art lovers and visual arts enthusiasts visiting Korea from all over the world.

The third article features 10 artists who observe their cities from a unique perspective and depict them through their personal experiences. In the past, the city was mostly perceived as a landscape, which led to the production of many figurative representations of the subject. More recently, however, works that do not directly feature the city are more prevalent. This article looks at how a city’s characteristics are expressed and how the diverse perspectives of young millennial and Gen Z artists express the new facets of the city.

The City as a Remote Control

"Go Straight There Without Transferring"

Ho Sang-gun,〈No Parking〉, Image provided by the artist.

〈The Meaning of 1/24 Second〉, a film shot by Kim Kulim in 1969, captured the appearance of Seoul at the time, including Samil Elevated Expressway, pedestrian overpasses, textile factories, and Sewoon Arcade. This film is at once fast and slow, the title itself meaning referring to its 24 frames per second. On screen, cigarette smoke rises and yawning individuals incapable of controlling the speed of the city appear. 〈The Meaning of 1/24 Second〉alternates between monochrome and color as it depicts a city that can no longer be seen. A basic quality of all cities is change. As I write this article in December 2021, my purpose is to discuss several aspects of cities that have appeared before us through artwork. The concept of the “city” assumed in this article is not simply the term we use for special administrative districts such as Gwangju, Busan, Incheon, Daegu, Mokpo, Chuncheon, Seoul, and Daejeon. Cities both remain administrative districts and exist alongside us as concrete places.

This article focuses on the dynamic and protean nature of cities as depicted by contemporary Korean artists. In turn, it will examine the virtual world, narrative methodologies, and artists’ tendencies to make use of their own bodies. Incidentally, the subtitle of this article (“go straight there without transferring”) was inspired by a newspaper article from December 2021. The article stated that equipping railways in the southeastern Yeongnam region with double tracks will make it possible within three years to travel from Seoul to Haeundae, Busan, in just 2 hours and 40 minutes. The article also shared information about the design of Taehwagang Station in Ulsan, which was built as part of the Yeongnam double-track railway project. The “image of the whale, the symbol of Ulsan,” was incorporated into the design of the station’s façade.1) The sense of speed (traveling without stopping or transferring) and the sense of longing for the old days are the twofold desires of the city predicated by the state’s current policy system. These desires represent the “no delays” attitude that assumes swift solutions, whether in the city or countryside, and the city’s profound history and rich context. How can they exist simultaneously in the city?

Today’s city is a blast furnace into which numerous things are poured all at once. Some parts of the city have aged and eroded because advancement and progress stopped after the city was planned. Furthermore, the respective locations of a city’s periphery and center continue to shift with the flow of capital. Depending on which perspective we adopt—urban and nonurban, center and periphery, real estate policy, personal narratives, or psychology—“city” can refer to different things. Park Hae-cheon, author of 『Concrete Utopia』 and 『Apartment Game』, had this to say about the Seoul of the 2010s: “Certainly Seoul simmered in certain areas that were heated up, but in the background, the city was rapidly aging and cooling down. The dual aspects created by this extreme temperature gap are definitely connected with Seoul’s unique phenomenon of aging.” Today’s artists also find themselves in a city experiencing the dual circumstances of “heating and cooling.”2) Artists create various perspectives for viewing the city through mediums both tangible and intangible.

The city is in the foreground

In the mid- to late 2000s, the city emerged as a major subject for painters. What was the reason behind this? One major factor is that the scenery of the city was changing before our very eyes through urban redevelopment. Various special features that appeared in art magazines of the time covered paintings that sought to demonstrate a feeling of nostalgia for cities’ vanishing times and spaces. But the city today faces issues distinct from recording or recreating changes apparent to the eye. Discourse on and technology of cities are virtualized depending on how far we are willing to extend what we call a city, as well as our very frame of perception regarding them. This is why the word “city” demands a new definition. In other words, the city today is not on the ground, but in the foreground. It is accompanied by the various names of the online world (metaverse, virtual reality, augmented reality) while provoking a sense of something foreign and evoking new sensations that are akin to nausea.

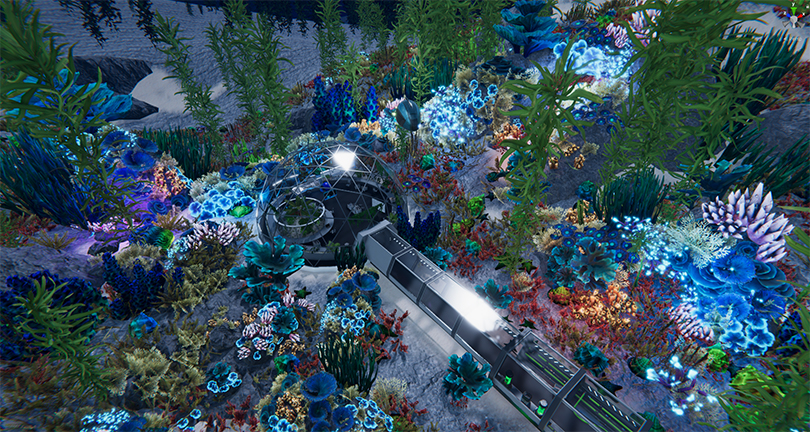

Ayoung Kim, 〈Surisol: POVCR〉, 2021, Image provided by the artist. .

Ayoung Kim, 〈Surisol: POVCR〉, 2021, Image provided by the artist.

The first aspect of cities I would like to discuss is the virtual one. 〈Surisol: POVCR〉, an artwork by Ayoung Kim, uses the medium of virtual reality (VR). While it appears to deal with the dimensions of space and the planet rather than the city, experiencing this work shows that it is based on a coastal city. Space-time unfolds beginning with the command to “awake” inside the space-time of a work that is reminiscent of a parallel universe. This work disrupts the vision, parallelism, and kinesthetic senses of viewers. While 〈Surisol: POVCR〉might appear to be based on a virtual laboratory on the ocean surface, it also contains kelp, an age-old local specialty in Gijang, a region of Busan. When we enter the city of Busan as a VR space, the existence of the real Busan region known as Gijang makes possible a new urban experience for those who have “boarded” Kim’s work—entering the exhibition, taking a seat, and entrusting their body to the VR equipment. This is a city that transcends the sensation of entering on foot—it is a complex entity in which waves and tsunamis come toward and rush through our entire bodies at the speed of light .

Kim Heecheon, 〈Sleigh Ride Chill〉, 2016, Image provided by the artist.

Kim Heecheon, 〈Sleigh Ride Chill〉, 2016, Image provided by the artist.

Technology of “smart cities” are changing, and so are artists’ methodologies for handling the subject of the city, which is emerging as the object of remote controls or space-time controllers. In the space of cities entered through the following procedures and steps, the drive of reality heads toward diverging goals . Roads extend in various directions and appear to be blocked as they try to break into other ways. When such sentiments appear in artwork, they overlap with the data of the remote movement of cities’ real and virtual aspects. A series of works by artist Kim Heecheon links the way the city is viewed and handled with the exterior of the city and the shell of the human subject’s body. Kim’s video work 〈Sleigh Ride Chill〉(2016) deals with the concept of the megacity and the reality and data inside cities that enter our personal smart storage devices. Past and present are disrupted in the political events shown in the work. Replete with loudspeakers and Korean flags, these demonstrations are constantly held around Gyeongbokgung Palace, a nexus in Seoul leading to the ancient Sungnyemun and Gwanghwamun Gates, City Hall, and Cheong Wa Dae. The artist moves between classic narratives and elaborate sensibilities, navigating streets that are related to a newly used method of transformation. The city as an abstraction and the city as a background synchronized with the body/mind move both closer and farther away. The zoom in and zoom out of a camera is another way of saying, “Adjusting the production of viewpoints.” The city of Seoul that appears in Kim’s work—a space of movement in a certain direction—accelerates until it reaches its destination or is destroyed.

Gim Ik-hyun, Exhibiton view of 〈A Future Where Everyone is Connected〉 , 2016, Image provided by MediaCitySeoul 2016, Photo by Hong Chul-ki.

Gim Ik-hyun, Exhibiton view of 〈A Future Where Everyone is Connected〉 , 2016, Image provided by MediaCitySeoul 2016, Photo by Hong Chul-ki.

Gim Ik-hyun’s 2016 work 〈A Future Where Everyone is Connected〉 can be described as a system of “photography.” The subject of his photography is Seoul. The artist’s problem is the method by which today’s cities and geography are recognized through geographic information technology. Gim presents specific buildings that can be seen in the city of Seoul and familiar winding alleys and walls in Seoul’s Jeong-dong neighborhood. Although these photographs might initially appear to all simply be “photos shot in Seoul,” they are a product not of homogeneity but of heterogeneity and difference. After shooting several photographs, the artist puts them together to present urban landscapes in panorama format. Inspect these photos for just a few more seconds, and you will see that the grid of horizontal and vertical gray lines is not aligned with the buildings. Rather than finding cracks in the buildings, the artist has “made an image by compressing and attaching” his photographs. Gim wrote the following while working on this project: “The real and virtual are now barely distinguished by their degree of density and resolution. [. . .] When I wander for a time through the Seoul composed of these images, I find myself thinking of a sleeker future in which their assembly will be too solid for a crack to show. And when I sometimes spot a dark gap in these images, I call to mind the hard work of those reconnaissance satellites from the 1960s.” 3) The artist’s note shows that his observation of the city is tied to questions and doubts about the technology that senses and records cities’ geographic information. The sort of “technology” that records and mediates a city determines the perceptive methods and abilities of the people living inside the city’s systems. According to Gim’s research, Google acquired the geographic information company Keyhole in 2004; the application Photo Sphere, which enables smartphone users to take 360-degree panorama photographs, was launched in 2013. As this suggests, the artist’s work interrogates the relationship between the city’s past and future and the relationship between the real and the virtual as they can be experienced by the individual.

Oh Sukkuhn, Exhibition view of 《Enemy Property》, Image provided by the artist.

Oh Sukkuhn, Exhibition view of 《Enemy Property》, Image provided by the artist.

The methodology of narrative: scattered cities

For our second observation of cities, let us examine how they appear in the methodology of narrative. Here, “narrative” refers collectively to methods of artistic research, history, and observation. As a meeting point for the city and the individual, history continues to provide artists with a subject they must untangle. Making a city today is different from plans to repair ruins. Under a system of collective control in the modern and contemporary history of the Republic of Korea, which remains both a divided state and a military state, several cities are locations in which a collective agenda lies scattered in a continuing political situation. At this point, the city is itself a subject and a setting in which memories of war and division collide alongside personal and collective narratives. Artist Oh Sukkuhn’s method of studying Gyeonggi-do and the city of Incheon includes field surveys, interviews, and policy proposals while alternating between the existing frameworks of sociology, geography, and history. As an artist who has researched various cities, Oh presented the results of his research of Incheon area houses formerly occupied by Japanese residents through photographs, installations, and floor plans in the exhibition 《Enemy Property》, held in Buyeon, Incheon, from September 25 to October 11, 2021. Along with Japanese artist Yusuke Kamata and Korean architect Lee Ui-jung, the exhibition both examined how the culture of Japanese homes changed in the past (that is, following Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule and the Korean War) and also proposed policies about how the cultural legacy of structures once called “homes of the enemy” should be used today.

Exhibition view of 《Jane Jin Kaisen: Community of Parting》, 2021, Art Sonje Center ⓒ 2021. Art Sonje Center. Photo by Kim Sang-tae.

The past and present also coexist in Jane Jin Kaisen’s video work 〈Community of Parting〉(2019). While shooting footage of Jeju Island’s women divers, known as haenyeo, Kaisen discusses the current state of nature, objects, and shamanism on her home island. Born on Jeju and then adopted, this artist’s story is inseparable from the island. She touches on the issues of personal confession, intersubjectivity, the state, and communities of women. The life of shaman Koh Sunahn, a survivor of the Jeju Massacre; the poetry of Kim Hyesoon; and historical facts of the Korean War are reborn in Kaisen’s images of wholly concrete objects. Jeju, as a city, is a rich storehouse of primeval and unchanging nature and history.

Koo Donghee, 〈Flight: Horizontal Lines〉, 2020, Image provided by the artist.

Koo Donghee, 〈Flight: Horizontal Lines〉, 2020, Image provided by the artist.

At the same time, the term “city” moves beyond a label for specific administrative regions, expanding into a universal signifier of land and sculptures. Here, cities are ready-made, being places that are “already there,” pre-existing systems. 〈Flight: Horizontal Lines〉, a work by Koo Donghee shown at Deoksugung Palace in 2020, is the unique product of the artist’s collection, research, and survey of public art pertaining to cities. In a number of video and installation projects, Koo has captured on screen the relationship between solids and planes and the geopolitical issues of urban spaces and pungsu jiri (geomancy). In 〈Flight: Horizontal Lines〉(2020), the artist gathered images of public monuments around the country that can be found under the search keyword “flight.” After finding images of such statues in 15 cities around the country, she altered their format and colored them to index materials such as iron, wood, and metal. After transforming these urban symbols, she shrank them into miniatures and made them buoys that float in water. It was striking to see several small fluorescent statues bobbing in the pond at Deoksugung Palace. In Koo’s plan, the grandiose figures standing in various cities around the country, defined by the word “flight,” became trivial objects exploring the boundary between plaything and monument. As it reminded viewers of the conventionality of public monuments found in every city, the work illustrated the artist’s multifaceted interpretation of the production of urban structures.

Ho Sang-gun,〈Namsan and Weather 07(Spring)〉, 〈Namsan and Weather 06(Summer)〉, 〈Namsan and Weather 05(Autumn)〉, 〈Namsan and Weather 13(Winter)〉, pencil and color pencil on paper, 354X277mm, Image provided by the artist.

In his work, Ho Sang-gun continues his observation of various urban locations through the lens of microhistory. 〈Namsan and Weather〉(2017–2020) is a series of occasional drawings of N Seoul Tower on Namsan Mountain in Seoul that the artist produced over the course of four years. The artist selected the tower as a landscape while looking out of his window. In these pieces, drawn on paper with pencils and colored pencils, N Seoul Tower is sometimes invisible in the dark of night, and at other times, such as when the sky is blanketed in yellow dust, it is only seen as a blurry outline. Ho tests the actual landscape before his eyes the way he might feel the fixed exposure of a smartphone camera. Ho’s observance and recording of specific urban scenes not as fixed objects but as changing “conditions” was influenced by our current habit of taking pictures with the smartphones we always carry. By drawing what is in front of him, the artist is faithful to the true record of the city. The micro-scenes and routine customs of the city are revealed in another piece by Ho called 〈No Parking〉 Series, a collection of drawings of objects such as rocks, flowerpots, chairs, and garbage placed in alleys to signify that parking is not allowed there. By marking areas such as (1) Mullae-dong, (2) Gyeongnidan-gil, (3) Euljiro 1-ga, and (4) Near Sangsu Station, Ho can remember exactly where in the city the objects were located.4)

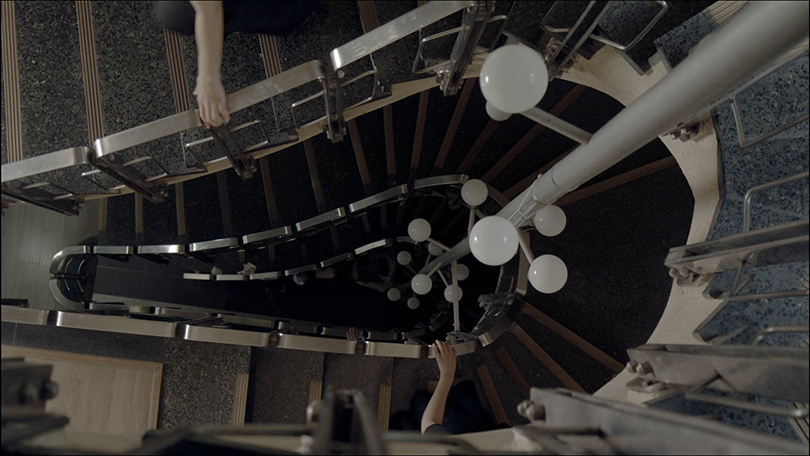

Park Sun-ho, 〈In the Glare of Sagan〉, 2021, Image provided by the artist.

The narrative of cities evokes buildings as main speakers and also invites the new speaker of women. With the work 〈In the Glare of Sagan〉 (2021), Park Sun-ho, an artist in her late 20s, deals with the inside and outside of a dark building built in 1975 in the neighborhood of Sagan-dong.5) With its spiral staircase and round lighting fixtures, this building belongs to an organization that has long engaged in activities related to publishing and print culture. In this work, Park overlays the Korean Publishers Association building with the hands of a woman flipping through an old album from the basement storeroom, the lush greenery of Songhyeon-dong viewed from a rooftop, and a framed poster of the 1970s slogan “books belong to all” hanging in the building. The speaker in this brief video is a building of several histories, allowing viewers to see the viewpoints of the city that have been disseminated as the stories of finely fragmented subjects.

Park Sun-ho, 〈In the Glare of Sagan〉, 2021, Image provided by the artist.

Walking into the city

The third aspect of cities revealed in artwork is the movements of the artists themselves; this is a very important quality. Holding the camera and their own instructions, artists walk into the city and emerge later. Allow me to quote once again from the aforementioned piece by Park Hae-cheon. Park wrote that in Korea, “urbanization was a method of moving to a higher class and a narrative of geographical movement provided on a limited basis to those born between the 1940s and the 1960s.” 6) The point here is that urban living zones have been being reorganized into “cube ecosystems” since the 2010s. Let me draw your attention to works that recognize or escape this “cube ecosystem” inside space-time experiences that shrink the city into a house, and the house into a room. In terms of modern-day trends, this is linked to attempts to experience the city with the body (including research thereupon). Song Joo-won’s videos depict figures dancing through the backstreets of the city. Figures moving between narrow alleyways, rooftops, old houses, and buildings grapple with the city’s old, artificial charm and the traces of people’s lives there. The city and its buildings, houses, and yards may be frozen in place, but women dance, sometimes in an even bigger group , first gathering together and then moving apart. Song’s works 〈I Am a Lion〉 (2019) and 〈Pung Jeong. Gak: A Town with a Blue Hill〉 (2018) use 42 stairs, light from skyscrapers, and the buildings around Seoullo 7017 to help us perceive the city of Seongnam and Seoul’s old neighborhood near Seoul Station, respectively. 7)

Song Joo-won,〈Pung Jeong. Gak: A Town with a Blue Hill〉 (2018), Image provided by the artist.

Song Joo-won, 〈I Am a Lion〉 , 2019, Image provided by the artist.

As this article examines the urban tendencies that appear in these works of art, the three aspects of cities blend together to create new forms of speaking and writing. The methods relating to the virtual, narrative, and direct personal experience overlap with each other when they appear in artwork. In the video 〈New Fuse Box〉 (2021), Jung Eu-gene, a woman artist in her 20s, deals with the confusion between personal accounts of the city and public history with a high-angle perspective and the voices of her family. This video overlaps two speakers—her mother and older brother—with the artist’s experience of life in an apartment complex in the Seoul neighborhood of Gaepo-dong. Her mother’s interest in real estate investment and her older brother’s engrossment with the fluctuations of cryptocurrency present Gaepo-dong, known as a stronghold of ambition, as yet another object of individualized desire. Born in 1995, the author imagines a new home between the generation of her parents, who view the city as the ground beneath their feet, and another generation that views cryptocurrency as more important than the ground itself.

Jung Eu-gene,〈New Fuse Box〉, 2021, image provided by the artist.

This paper sought to explore aspects of how Korean artists today pay attention to the concept of the city. It examined cities as they appear in the foreground of the online and offline worlds, methodologies of building narratives, and the performative aspect of personally walking into cities. Even if contemporary Korean artists do not directly invoke the city in their titles as novelist Sang Young Park did in his novel 『Love in the Big City』 (2019), they are always in dialogue with and confronting parts of a specific city. We are now in the third year of a pandemic in which it is difficult to experience breathing in fresh air as one does when walking through an unfamiliar city. At such a time, we need new eyes and a fresh vision for viewing cities.

1)“In 2024, it will be possible to travel straight from Seoul to Haeundae without a transfer in 2 hours and 40 minutes,” Money Today, December 12, 2021, https://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2021121014124644976." https://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2021121014124644976

2)Park Hae-cheon, “Heating and Cooling, Two Aspects of Seoul in the 2010s,” Solid City Exhibition Brochure, Sehwa Museum of Art, 2021.

3)Gim Ik-hyun, an artist’s note written in 2016.

4)https://bgaworks.com/pages/4

5)This piece was shown in Punctuation: New World Coming (September 8–12, 2021, Sfactory, Seongsu-dong, planned by Lee Sang-gil and Hyeon Si-won), an archival exhibition that documented the 70-year history of the Seoul International Book Festival. The festival is organized by the Korean Publishers Association, which was also behind the construction of this building in 1975.

6)Park Hae-cheon, ibid.

7)See the website of the Seo-Seoul Museum of Art’s pre-launch program (http://www.seo-sema.kr). Song Joo-won’s videos have been screened in several exhibitions, most recently in Signaling Perimeters at the Nam-Seoul Museum of Art (September 28–November 7, 2021).

Related articles

[Art in City] Public Art(1) Borderlessness in Public Art

[Art in City] Public Art(2) Public Art in Seoul - How Well Do You Know Them?

[Art in City] Art Spaces(1) Seoul - Untitled & Titled Spaces

[Art in City] Art Spaces(2) Busan - Is Busan Really Culturally Alienated?

[Art in City] Art Spaces(3) A Guide to Daegu‘s Exhibition Venues: Latest Edition

[Art in City] Art Spaces(4) Gwangju’s Cultural Topography Meets Its Urban History

Seewon Hyun

Working as an independent curator, she plans exhibitions and writes on images and art.