Features / Focus

Video works Occupy Exhibition spaces – An Interview with Kim Woong Yong

posted 03 Jan 2023

Is the genre division between art and film still valid? Nowadays, audiences enjoy any interesting video work, whether it be in a museum or a theatre. They are not bound by the classification used by professional video artists or filmmakers, nor by the spatial characteristics of white cubes or black boxes. “FILM_Text and Image," an MMCA film and video program that is presented at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Seoul venue, recently introduced the cinematic works of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Susan Sontag, etc. The 9th annual exhibition of the Buk-Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), “Title Match” invited Im Heung-soon and Omer Fast, both of whom are working as video artists and film directors. 2022 Jeonju International Film Festival also featured a special section “Borderless Storyteller”, showcasing works by eight artists including Kim Heecheon and Moojin Brothers, which was published as a book by the same title.

The ARTRO is featuring the “Video Works Occupy Exhibition Spaces” series of articles. This series features a written piece titled “Reading between the Mirror and the Screen”, by Kim Mijung, who curated “Media Punk: Belief, Hope & Love” in 2019 at the ARKO Art Center, followed by introductions of four artists (or collectives): Kim Woong Yong, Ryu Hansol, Park Sunho and 업체eobchae. We hope this feature article will serve as an opportunity to reflect upon the video images that cross these genres and spaces today.

Kim Woong Yong is the artist who discovers the reactionary force behind obsolete records and technologies. Kim simulates the process by linking the reactionary force into the circulation of memories. He produced real-time video performances such as Okhotsk High Pressure, Avoided Names Under the Hard Skin, Night and Fog, etc., as well as the video works including Junk, Demo, and Wake. Kim has participated in several domestic and international exhibitions. He has also translated the book Exhibiting the Moving Image: History Revisited into Korean.

kimwoongyong.net

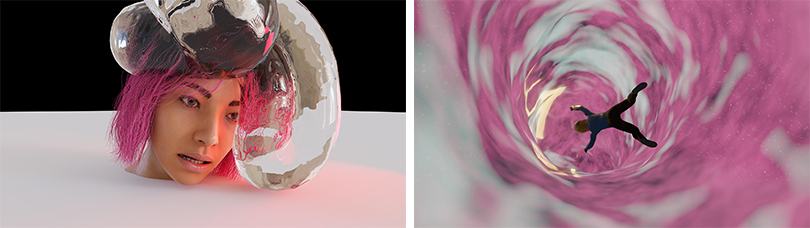

Eliza (upcoming), CGI animation, color, Korean-English, 5min.

Can you introduce yourself please? We would like to hear more on the subjects that you are interested in.

I am interested in the broken, the excluded, and things that become socially and technologically obsolete over time. In them, the context of destruction, movement, and heterogeneous force and failure exist simultaneously. And when those traces are places in the current context through the medium of a screen, I find a point where they can be amplified by the senses. Based on this thought, I produced real-time video performances such as Okhotsk High Pressure, Avoided Names Under the Hard Skin, Night and Fog, etc., as well as_ Junk_, Demo, and Wake.

Is there any reason why you chose video images as a means for some of your works, amongst various media?

I had the opportunity to face the other side of an image. Although a bit trivial, this led me to think about what it means to create an image. This occurred when I first learned digital editing in university. After finishing editing, I was checking the shooting version, when I realized that the sound in the timeline came from a completely different source, rather than the source from when the video was shot. Even within the same subject, I felt as if I had experienced two different realities simultaneously: the reality at the time of shooting as well as another one created via editing. Meanwhile, I realized the process of my recognition that what I believed I knew was actually wrong. While exploring the medium of video like this, I continued to work while considering the mysterious possibility of understanding the process of my own thoughts.

To me, a screen is neither a window nor a mirror, but an opaque dimension. However, the images created behind the screen expose the contradictions that are easily exchanged and influenced, as if they reflect the rest of the world transparently, continuously combining with the present. Looking at the traces attached to the record in the process of circulating inside and outside the screen, I tried to virtually construct the area where the sensory crystal was formed, and I thought it was a crystal that integrates the present. For this reason, the screen within the screen appears in my work, and what is considered to be the past develops into a realm of synthesis with the disparate graphic mass of the present.

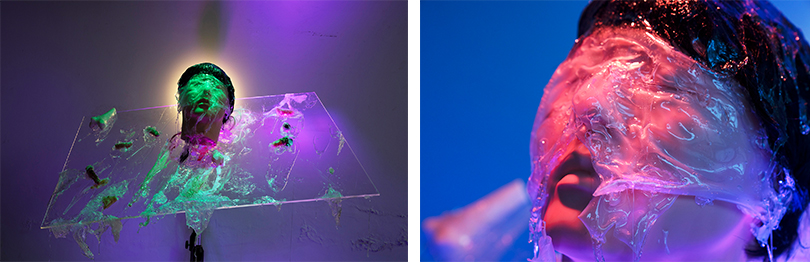

In this way, I consider the exhibition to be a filming set, and proceed to do screen work that reflects the sense of a stage with theatrical lighting. Recently, I am working on Eliza, a CGI animation about the A.I. psychological counselling program ‘ELIZA’ developed in 1996. I am also editing Gray Matter, a documentary about migrant workers, migrant images, and the sensory qualities of the brain that mediate each other. In addition, I started the Organum series as an attempt to construct a film set from another dimension, by expanding the circulation of moving images and screen into a thin curtain and installing images of the characters in the work.

Wake, 2019, single-channel 4K video, programming linked moving light, color, stereo, Korean, 19min 46sec.

A variety of visual materials are employed in your work, including movies, animations, documentaries, news, advertisements, and games. Since you work by combining heterogeneous images and sounds, I am curious about how your work is created. Please introduce the overall work process from the archiving stage to the production of the work.

The visual materials you mentioned look very different, but they are all related to the record of obsolete things and the format that mediates them. I am not interested in restoring the past like a museum. Rather I am interested in the objects of the past, which were once hidden from view. So, mistakes and errors are exposed by chance, and in this process, I detect the contours of the structure connected to the present. Thus, my attention is directed outside of the visible path to what material history is composed of, including what contents and standards it lends to our current perception. There is a conflict between something that has lost its meaning and the great force that has pushed it out of its path. Here I discover and extract things derived as audio-visual materials.

I think these sensory remnants are the crystallization of this collision. This allows me to clearly see the gaps between the layers and connect them to related things. This paradoxical combination thus opens up the possibility for me to understand and mediate the present as multiple streams. It feels especially strange when anachronistic things stand out, and that's how the recent image reproduction of producing method and discarded images lead to that interest. For example, in the mass-produced horror (ghost) films of the 1970s, I find the voices lose their own homes, and retain the concentrated time and senses of the period. I extracted similarly dubbed voices from these sources and converted them as if the performer was lip-synching. The appearance of these ghosts is repeated in works such as Okhotsk High Pressure, Avoided Names Under the Hard Skin, Soft Copy Drama etc.

Gray Matter (upcoming), single-channel 4K video, B&W, Tagalog, 15min.

Avoided Names Under the Hard Skin, 2014, real time video performance (HD video, 2 cameras, video interface, 3 variable set), Korean, 60min.

As you mentioned, it is unique that the events of the past and the present are called out at a point in time that is neither the past nor the present, and depicts a form that is neither completely forgotten nor completely non-existent. Such methods stand out especially in works dealing with historical events, such as in Wake or Wavelength. Could you elaborate upon what you intended?

The two works you mentioned take are inspired by the years 1980 and 1996. This period itself connotes an excluded record, and to the extent that it is damaged, we see that it is more powerfully converted and derived into various technologies that reproduce and spread it into various layers. Looking at these technological differences makes us think not only about the factors that make the difference, but also about the forces that make up the event and what has not been achieved.

Specifically, the main elements extracted from Wake and Wavelength are voice, lighting, trivial memories, rehearsal, and script. These elements do have certain functions eventually, yet also connote the notion of time, which is an invisible and temporary stage before also becoming a result. This might remain in one’s imagination. But, assuming that the traces of these senses are extracted from the records left by all the films and moving image cultures that have existed in history, if these heterogeneous things are organically combine, they will create a huge virtual moving image with a very long running time. If we push forward with this idea, we may eventually be able to simulate the present by looking differently at the memories and customs that our brains have learned.

Furthermore, your work seems to blur the boundaries between the unreal and the real worlds by overlapping various events and fictional elements, such as the present time when we, the audience, watch video works, the past time when the actual historical event occurred, and many more. Based on the video work, you have also presented a real-time performance as well. As such, ‘time’ is an important element in your work, and I would like to hear what you think about the relationship or influence between time and video images.

In my work, time corresponds to the process of dissolving the results of events that have already occurred in the contents and sensations associated with them. This is why lines or gestures are repeated in different sequences within the same work. In this process, the stereotyped story frame collapses, and only the senses remain, which can be perceived only vaguely. This requires a different way of experiencing time than following the story sequentially. In particular, we may simply hear the content of a voice. However, it is the speed, volume, intonation, hesitation, emotion, attitude, social context of the word, and mistakes included in the voice that lead us to perceive with our senses and, more importantly, through the experience of time. Likewise, there are various elements that can be reduced to the senses in the description of memory, the composition of sequences, and the arrangement of lighting and objects. As a result, I think that a virtual time block is formed by synthesizing and colliding the present time, which is assimilated by viewing it from the outside, with the image created in the past, behind the screen.

Meanwhile, to me real time has to do with artificially creating time. We who exist in the present are not conscious of whether time is real-time or synchronous. In contrast, in my performance work, shooting and screening happen simultaneously on stage through an interface, and when a performer lip-synchs his/her lines in front of the camera, that performer’s face is immediately projected onto the screen as an edited screen, making that time artificially visible. Therefore, for me, real time plays a role in revealing the contradiction that present-reality-real time is not the time given by nature as it is, but rather the time that is constructed and created. Furthermore, I tried to visualize the idea that the present is composed of different kinds of temporal networks that are invisible in the web of time.

DEMO, 2018, 3-channel synched video, B&W, color, stereo, Korean-Japanese, 17min 30sec.

DEMO, dealing the incident of the Japanese Red Army, includes a 3D simulation game in which the audience experiences a series of events from the perspective of a member of the Japanese Red Army. Unlike other works that deal with real events, it uses a first-person point of view game format to fixate on the person experiencing the event and being immersed in it. While the video is projected towards the audience, the games draw the audience. How do you think this difference in direction affects the way the narrative is led?

If the audience actually plays the game in the exhibition room, the expression of ‘drawing’ the audience would be more appropriate. But apart from that, I focused on revealing the method and process of simulation. The first-person point of view game is a method in which the player's sight and space are created according to the player's own movement. By maximizing the sense of space, even when moving on the ground, it gives the illusion of swimming in space in a vacuum. In this context, the hijacking of a plane bound for Pyongyang by a Japanese Red Army armed with virtual images and the crash landing at Gimpo Airport seemed to be a comical and tragic vacuum between simulation and reality. The Japanese Red Army, an extremist communist revolutionary faction in the 1960s, was mostly composed of young people in their early 20s, who tried to realize a different world. However, at some point they became separated from their lives and collapsed due to the ideology of this image. In this way, death, games, and distorted images of utopia were mixed together to reconstruct them into a crash-landing event, a vacuum in history.

The three channels in DEMO were created with immersive game screens in mind, but the audience will rather face the record of a collapsing simulation. The scenery inside the airport, which the audience encounters while following the movement of the characters connected to the network, is created by the movement of the characters themselves, just like the scenery of a first-person game. This landscape is connected to the records of the crash and other images that the characters longed for, and the space was designed to fail in this game due to the collision of the images. I think these vacuum algorithms are deeply embedded in the ambivalence that new media derives.

Video is not only a visual medium, but also an auditory medium. You also work on sound and performance. What do you focus on when dealing with sound, especially in video work?

In my work, sound appears on its own, rather than as an auxiliary effect, primarily because it is not completely assimilated into the image and therefore looks artificial. This is especially true when the same voice and lines appear over and over again on different faces, or when a different voice is lip-synched on one face to follow the shape of the mouth. So, I think the closest thing to a ghost is not a visible form, but rather a sound. And what I'm trying to do in my work is to open the door to those various senses that approach the record in this way.

Organum I, 2022, acrylic board, dummy head, LCD moving light, dimension variable.

In the past, video works have been ‘screened’ in so-called black box spaces represented by movie theaters or cathode-ray tubes. Now as various video works are displayed in the ‘white cube’, i.e., the gallery space, the boundaries between genres are blurring. Furthermore, the spread of mobile devices and the advent of the Internet era allow video images to be viewed anywhere and everywhere. I would like to hear about what you consider or contemplate the most when presenting video work in white cube spaces.

I believe that white cubes and various media, as well as black boxes, are not simply different types of physical space, but each also function as a single medium. However, these media and exhibitions involve other practical issues, which require an explanation from institutions and support, rather than hierarchy or shifts between them. So, choosing between the institution and a digital platform such as the Internet cannot be exactly dichotomized, even if it seems to be an aesthetic problem where one must choose only one answer. In my case, my work called for a certain space and production cost and required a form of performance or moving image installation that did not meet financial interests.

In other words, the production and exhibition of my work was only possible in the "gallery space called White Cube", especially with the support of national and public institutions. Exhibiting my work using a digital platform, which is something completely unrelated to the institution, is included in a broader area of private activities rather than that of public ones. Nonetheless, if one sees an artistic value in a private act, this would later make it possible to include it. If a digital platform is created with support from an institution, it can be a good opportunity to harmonize the system with other activities, even if it is not possible to ignore points such as setting a deadline for use of the platform, or compliance with contracts regarding content composition.

However, this is hard to generalize, as there are some case utilizing the result as a tool, but which have nothing to do with these values. The digital platform I'm using now serves as an interface between the exhibition, portfolio, and showcase, but I'm envisioning work that expands on this middle ground. In the end, space, institutional support, and expression of media should be mutually complementary in order to become more effective.

Do you think there is ‘a form of speech only pertinent to video’, to quote Curator Kim Mijung? We would like to hear your thoughts on this.

I think the ‘form of speech only pertinent to video’ is where we understand our action as a series of processes. Therefore, the expression and form of moving images, including video, camera, and animation, are related to how we perceive time and space as both an action and an ethical relationship, in the sense that we are included in the range of possibility/impossibility of the action, either directly or indirectly. Moving images not only simply describe whether or not something actually exists, but also make us unconsciously imitate the sensation of that action through our own actions. Yet, we can view the process in physical time. For instance, we will perceive one’s ordinary action of eating very differently and strangely by recognizing not only the face of the person who eats bread, but also the shape of one’s mouth, the strength of jaw one uses, the way of speaking while eating, one’s facial expression, and the time one spends to eat. In this regard, I think that historical narrative and the way we understand it have changed since the period when moving images became common, and they affect the perceptual structure of perceiving the world in a specific way.

Kim Woong Yong

Kim Woong Yong is the artist who discovers the reactionary force behind obsolete records and technologies. Kim simulates the process by linking the reactionary force into the circulation of memories. He produced real-time video performances such as Okhotsk High Pressure, Avoided Names Under the Hard Skin, Night and Fog, etc., as well as the video works including Junk, Demo, and Wake. Kim has participated in several domestic and international exhibitions. He has also translated the book Exhibiting the Moving Image: History Revisited into Korean.

kimwoongyong.net