It was in the 1990s that the national art authorities of Korea and Australia first discussed the prospect of holding reciprocal exhibitions that would spotlight each nation’s respective art scenes. Twenty-five years later, the two countries are now witnessing vibrant exchanges in contemporary art. Currently in its eighth edition, the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane, Australia, has played a major role in promoting such exchanges, becoming widely acknowledged as a foremost international venue providing the most definitive look at Korean art today. Australian writer Alison Can'oll, founder of AsialinkArts, discusses Australia’s enthusiasm for Korean art seen at this year’striennial, while Yeon Shim Chung introduces the works three Korean artists who participated in the event (Choi Jeong-hwa, Haegue Yang, and Siren Eun Young Jung). Read on to further explore the unique intersection between Korean and Australian art.

KOREAN HEAT at the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Brisbane

Over the last 22 years, the most extensive exposition of Korean art anywhere in the world outside Korea has been the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane. Does that surprise you? It does me a little, and it makes me think how important the APT has been – the role it has had, not just at the beginning by its sheer chutzpah and phenomenal backing by the Queensland Art Gallery and through the public-purse, but its continuing weight of commitment over all these years: its unflagging amount of intellectual energy, creative thought, engagement and sheer physical work. It has changed, but its focus and energy have not tapered off.

The rollcall of names in the eight APTs to date includes almost all Korean artists of note of the last two decades, including some who gained very early international recognition in Brisbane. In all, over 30 Korean artists have been invited to show. Significantly, many works have been major site-specific commissions, among them a selection that have been acquired by the Gallery, making it one of the best(the best?) collections of contemporary Asian art in the world. It also includes artists who have faded from view – a reality if the selections are to be as adventurous as they should be. My claim about the APT’s role with Korea comes from questioning where else in the world has this work had such a consistent and high level of exhibition. The Venice Biennale with Korea’s own pavilion is the closest that comes to mind, with usually just one artist’s work shown.

L) Choi Jeong Hwa I, too, want to go to your side and become a flower – Superflower, 1995, fabric, compressor fans, electric regulators. Courtesy the artist

L) Choi Jeong Hwa I, too, want to go to your side and become a flower – Superflower, 1995, fabric, compressor fans, electric regulators. Courtesy the artist R) Gimhongsok Canine Construction,2009, resin. Courtesy Queensland Art, Gallery Collection

Like the Korean Pavilion in Venice, the one aspect of the APT that has not changed is the recognition that each artist shows work on their own merits. Pat Hoffie once memorably said that the criterion at the beginning was “what’s hot” and the selection still seems to follow that, channelled by the Gallery through various aesthetic or geo-political balances, as well as a desire to show new work. The trends of the whole Triennial through its history has been the inclusion of foci that shine and then retreat, like North Korea, or the Mekong, or New Guinea, or the Middle East, or this year Mongolia. For South Korea, this has meant a slight rise and fall of “representation” but no change of focus as such. It is the same mix of what is “hot”.

The circumstances have changed over time. In the 1990s, Australian artists and curators were close to colleagues in Korea. The APT led the way from 1991 with Queensland Art Gallery Director Doug Hall’s visit to the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul to set up the first dialogue. Asialink followed, when I wrote a report and recommendations (commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade) in 1993 about possible future exchanges in the visual arts, resulting in the development of residencies, curatorial visits and exhibition exchanges – including the first exhibition of contemporary Korean art to be shown at the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of NSW in 1998, Slowness of Speed, curated by Kim Sun-jung. Others like Gene Sherman and Hannah Fink developed projects, Hannah, in charge of the special Korean edition of ARTAsiaPacific, published in Sydney in 1996,edited by Roe Jae-ryung. Roe went on to write Contemporary Korean Art, published in Sydney by Craftsman House in 2001, a response she says to the lack of “information and scholarship” about Korean art in English and hence the “marginal place of Korean contemporary art” in international publications and conferences. This book reflected the millennial watershed, following the simpler 1990s leading to the myriad wefts and weaves of the 2000s developing in Seoul, including a much more complex and varied relationship with international engagements, as articulated in this edition of Artlink. The sheer length of time of Korea’s involvement in the APT covers this major period of Korea’s emergence into the international art world.

L) Han Myung-Ok in her studio 1995. Photo courtesy the artist

L) Han Myung-Ok in her studio 1995. Photo courtesy the artist R) Yun Suk Nam Pink Room IV, 1995, mixed media, installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Hakgojae Gallery, Seoul

It goes from the tentative, unknown contact of 1991 through relatively simple years of engagement later in that decade to the complex layering of the Korean art world today. The Australian links in the 1990s were quite exceptional, making many Korean artists and curators familiar with Australia and vice versa, a legacy that has generally diminished, unfortunately, in the last fifteen or so years.

Since the 1990s, when Korean art was struggling to find its international place, this engagement has become much more fluid and seamless, but still worthy of comment in the context of the APT and perhaps any project wrapped in a nationally specified mantle. It is the issue that Korean art(amongst other lesser-known cultural expressions) tended to be essentialised and exoticised, with choices made based on either overt references to Korean visual culture, or more subtle social references to, for example, Confucianism.

I give two examples of the discussion: Choi Eunju, curator of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul, and the first curator in Seoul to advise the APT in 1991, wrote in the 1st Fukuoka Triennial catalogue of 1999 on Contemporary Korean Art in Pluralism and the Issue of ‘Communication’, that the Tate Gallery Liverpool(with its 1992 exhibition Working with Nature), APT1, and An Aspect of Korean Art in the 1990s in Tokyo and Osaka were three exhibitions organised by foreign curators “who wanted to look into the substance of Korean art” and that “the common consciousness found in those exhibitions was to find the distinct nature of Korean art”. Ssamzie Space founder Kim Hong Hee further distilled this in a talk in Shanghai in 2007 later published in Seoul (Curating Differences: Aspiration and Dilemma of an Asian Curator, BizArt Shanghai). She highlighted that the official character of biennales and their insistence on “presenting national and regional characteristics urge its participants to present a distinct identity… [with the] significant risk of falling into Orientalism or ending up with “Counter-Orientalism” caused by self-peripheralisation”. She says that in her own curatorial selection for the Korea Pavilion in the 2003 Venice Biennale she wanted work of the “here and now” instead of “traditional Korean-ness”. But, as she explains, this was misread as “remote and difficult” and mostly dissatisfied the audience “who expected to find and sense Korean identity in terms of traditional motifs from the Orientalist and exoticist perspectives”. She worries about “Asia” as a biennial theme for the same reasons, but she concludes the key is “returning to one’s original roots” without it being exoticism or Orientalism and doing this within an international dialogue. She throws this out as the challenge for curators to come.

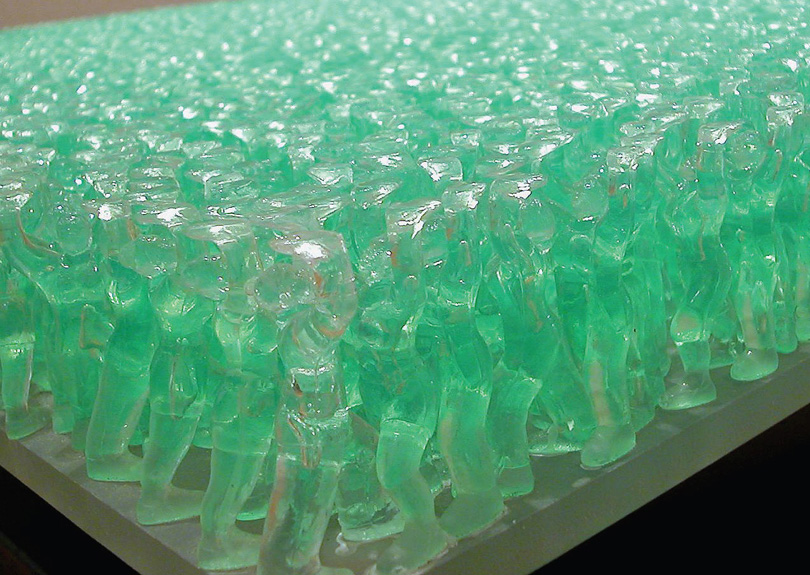

above) Suh Do-ho Blue-green bridge, 2000, acrylic figures, polycarbonate sheets, steel structure. Photo courtesy Queensland Art Gallery

above) Suh Do-ho Blue-green bridge, 2000, acrylic figures, polycarbonate sheets, steel structure. Photo courtesy Queensland Art Gallery For the APT, by 1996 the national overlay was put aside in both the catalogue and the installation, and that has for the most part remained the case today. But audiences still want to find the local sources of what makes this work from Korea what it is. Looking back over the Korean selections in the various APTs, these works come to my mind: Lee Bul’s sequin-studded fish (that despite the refrigerator started to be quite aromatic over the time of the show) in 1993, Yun Suk-nam’s luscious over-stuffed pink sofa teetering on its little spikey feet in 1996, Han Myung-ok’s delicate web of thread in 1999, the incomparable greats Nam June Paik and Lee U-fan along with rising star Suh Do-ho’s bridge held up by myriad little plastic workers in 2002, the blast of Socialist Realism from North Korea in 2009, and the mad bloated black-rubbish-bag dog of Gimhongsok in 2012. Is there something “Korean” that binds these works? A vitality certainly, and as Doug Hall has said “a lack of timidity”, but this would apply to most works in the APT.

If we peel back the layers, there will certainly be issues in all these artists’ minds that reflect their physical place and cultural background. Is it apparent? And is it important to find and recognise? No, on one level, and also yes, if we accept that in attempting to understand works of art better we seek out information on the circumstances in which they were made. The rest of this edition of Artlink would help any reader understand more about what art from Korea or by Koreans is today, but now there are also myriad publications, supported by a vast web of publicly and privately-funded organisations in Korea (including the major new government-driven arts centre in Gwangju), as well as the many international initiatives which include artists who happen to come from Korea, that can lead the viewer on to a richer understanding of each work of art.

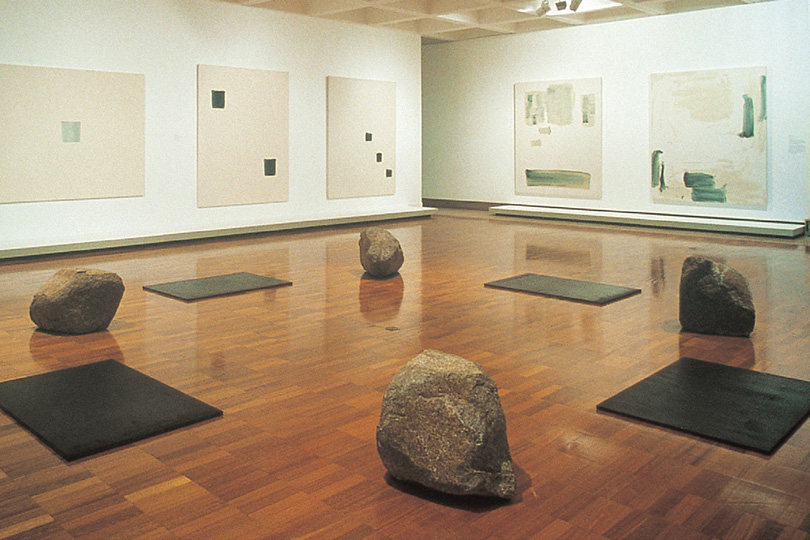

above) Lee U-fan Relatum, 2002 (foreground) iron plates, stones, installation at the APT 2002: Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane. The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy Queensland Art Gallery

above) Lee U-fan Relatum, 2002 (foreground) iron plates, stones, installation at the APT 2002: Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane. The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy Queensland Art Gallery ※ This article is published as part of a collaboration between Artlink magazine and Korean Arts Management Service. It first appeared in Artlink's special bilingual issue KOREA contemporary art now,V.35:4, Dec. 2015 for which KAMS provided advisory and translation services. Copyright the author and Artlink.

Alison Carroll / Asia art scholar

Alison Carroll AM founded Asialink Arts based at the University of Melbourne, and was its Director for 20 years until 2010. She was co-curator for the Korean selection at APT2. Author of The Revolutionary Century:Art in Asia1900-2000,(Macmillan 2010), her acclaimed TV documentary series A Journey Through Asian Art (2014) includes interviews with Lee Ufan and Choi Jeong-Hwa.