Exhibition view: 경로를 재탐색합니다 UN/LEARNING AUSTRALIA, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul (14 December 2021–6 March 2022). Ⓒ Seoul Museum of Art. Courtesy Seoul Museum of Art. Photo: Yoonjae Kim.

Blending perspectives across time and space, and through a number of tactics ranging from subversion to truth-telling, 경로를 재탐색합니다 UN/LEARNING AUSTRALIA represents Australia as a diverse enmeshment of narratives.

Commemorating the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Australia and South Korea, the special exhibition is being held on the first and second floors of the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) (14 December 2021–6 March 2022).

Exhibition view: 경로를 재탐색합니다 UN/LEARNING AUSTRALIA, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul (14 December 2021–6 March 2022). Ⓒ Seoul Museum of Art. Courtesy Seoul Museum of Art. Photo: Yoonjae Kim.

Co-curated by SeMA and Artspace in Sydney, the exhibition features work by 35 Australian artists and collectives including Richard Bell, Brook Andrew, and Yhonnie Scarce—all with the aim of rethinking, as the show's title suggests, Australia and Australian contemporary art.

Suspended from the ceiling in the museum lobby, Archie Moore's installation made up of 14 flags, titled United Neytions (2014–2017), evokes the feeling of entering an official, international space.

Archie Moore, United Neytions (2014–2017). Installation of 28 flags, polyester, nylon, zinc plated alloy. 28 parts in two sizes: 23 x 360 x 180 cm and 5x 180 x 180 cm. Exhibition view: The National: New Australian Art, Carriage works, Sydney (2017). Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney. Photo: Sofia Freeman.

Moore's brightly coloured flags revise Australian anthropologist Robert Hamilton Mathews' inaccurate mapping of the 28 Aboriginal nations in 1900. Each flag incorporates distinct topographic symbols, designs, and colours that are specific to each Aboriginal nation.

Referencing the Arrinda nation, one red ochre-coloured flag depicts the nation's central desert petroglyph as a black whirlpool. Another, representing the Kamilaroi nation, is patterned with diamond shapes: red, yellow, and black, with seven white stars set against a blue background.

Archie Moore, United Neytions (2014–2017). Installation of 28 flags, polyester, nylon, zinc plated alloy. 28 parts in two sizes: 23 x 360 x 180 cm and 5x 180 x 180 cm. Exhibition view: The National: New Australian Art, Carriage works, Sydney (2017). Courtesy the artist and The Commercial. Sydney. Photo: Sofia Freeman.

Together, these flags unsettle the idea of a single nation by reflecting the Indigenous communities that have effectively been erased by Australia's adoption of a national flag designed by its settlers rather than its traditional custodians.

In the absence of Aboriginal sovereignty in the region, Moore's flags invite visitors to unlearn Australia as it is known and see it for what it is.

Exhibition view: 경로를 재탐색합니다 UN/LEARNING AUSTRALIA, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul (14 December 2021–6 March 2022). Ⓒ Seoul Museum of Art. Courtesy Seoul Museum of Art. Photo: Yoonjae Kim.

Sharing the lobby is Taloi Havini's large-scale architectural installation, Reclamation (2020)—a long wooden arch made from Korean bamboo set on a rectangular wooden base. The structure depicts the framework of a house with Korean straw acting as its membrane.

A descendant of the Hakö people from north-eastern Buka in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, Indigenous knowledge and its practices are central to Havini's apractice, as evidenced by Reclamation, which was made in collaboration with Hakö clan members.

Taloi Havini, Reclamation (2020). Cane, vine, steel, varnish. Exhibition view: Artspace, Sydney (17 January–23 February 2022). Co-commissioned by Artspace and the Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Zan Wimberley.

The structure is porous: at once a passage, gate, and plaza for encounter. Located on either side of the installation, two access points leading into the main exhibition space also guide visitors to Lennard Walker's two paintings, both titled Kulyuru (2020).

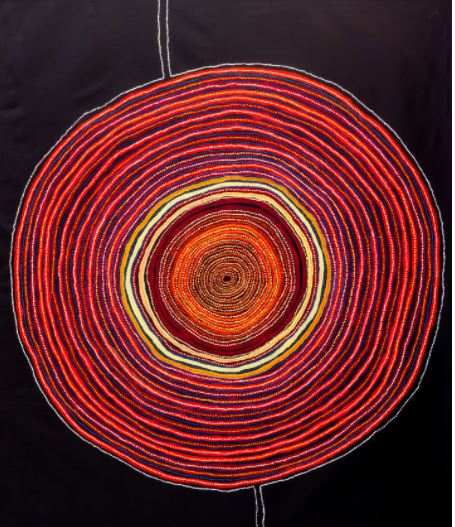

Kulyuru consists of concentric circles in vibrant shades of red, brown, and gold, evoking colours of the Australian landscape. Inspired by the Aboriginal creation myth of the Seven Sisters Tjukurpa and their pursuit of a carpet python across the land, marks depicting the massive rock hole where the creature turned for refuge, can be sighted in each painting.

Lennard Walker, Kulyuru (2021). Acrylic on linen. 230 x 200 cm. Courtesy the artist and Spinifex Arts Project. Photo: Amanda Dent.

As a point of departure, Kulyuru represents a way of painting that maps territory as much as it does memory and myth, thus creating a link to this exhibition's Korean title: 경로를 재탐색합니다, which means 'rediscovering the route'.

The invitation is to reconsider familiar and singular narratives through the charting of multiple representations and trajectories that dismantle colonial history by uncovering the depth of the land and the stories it holds.

Taloi Havini, Habitat: Konawiru (2016) (still). Single-channel HD video. 3 min, 43 sec. Edition of 5 + 1 AP. Queensland Art Gallery. Gift of the artist through the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art Foundation (2021). Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program. Courtesy the artist.

On the first floor, Havini's second work, a single-channel video titled Habitat: Konawiru (2016), shows a raft loaded with several leaves, a bag, and a small knife, which appears like a survival kit. The raft traverses a dense swamp area in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, offering aerial views so beautiful as to resemble a painting.

That beauty is later intersected by the voice of a Bougainville woman, who proclaims, 'the company poisoned this land, now we don't have any land,' as industrial relics of tailing pipes surrounding the Panguna copper mine come into close view.

Taloi Havini, Habitat: Konawiru (2016) (still). Single-channel HD video. 3 min, 43 sec. Edition of 5 + 1 AP. Queensland Art Gallery. Gift of the artist through the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art Foundation (2021). Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program. Courtesy the artist.

The Panguna copper mine caused tremendous environmental and cultural devastation after its opening in 1972. By contrasting the raft's journey through the natural landscape with ruins of the mine, Havini brings into focus the impact of such ventures on communities and land.

Expanding Havini's critique are two installations by Megan Cope, RE FORMATION (Part I) (2016) and Untitled (Extractions II) (2020), which highlight the fact that concrete, while the second most used material after water, creates untold environmental devastation.

Megan Cope, RE FORMATION (Part I) (2016) (detail). 1800 hand-made concrete shells lodged in black mineral sand. Dimension variable. Exhibition view: 경로를 재탐색합니다 UN/LEARNING AUSTRALIA, Seoul Museum of Art (14 December 2021–6 March 2022). Ⓒ Seoul Museum of Art. Courtesy Seoul Museum of Art. Photo: Yoonjae Kim.

Located on both sides of Havini's work, the first installation consists of two loose mountains composed of 1,800 handmade concrete shells lodged in black mineral sand, a land-based by-product of the mining industry similar to 'new rocks', which form in the ocean through an aggregation of geological materials and plastic debris.

Cope's shell mounds refer to mollusc middens, an accumulation of discarded animal bones and shells that act as archaeological markers of inhabited sites. Middens are commonly found in places where generations of Aboriginal communities have lived and gathered, and reveal important information about Aboriginal knowledge systems and relationships with lakes, rivers, swamps, and seas.

Megan Cope, RE FORMATION (Part I) (2016). 1800 hand-made concrete shells lodged in black mineral sand. Dimension variable. Exhibition view: 경로를 재탐색합니다 UN/LEARNING AUSTRALIA, Seoul Museum of Art (14 December 2021–6 March 2022). Ⓒ Seoul Museum of Art. Courtesy Seoul Museum of Art. Photo: Yoonjae Kim.

Now protected as heritage sites, shell middens are still found near water bodies in the Australian landscape, including the artist's homeland Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island). In the past, they were often destroyed by colonial settlers to produce mortar for the construction of buildings, making them both monuments to Aboriginal sovereignty and evidence of colonial violence.

To unlearn Australia is to begin to understand what it means to navigate a place while grappling with the residual violence and legacies of colonisation.