Energetic efforts are under way in the Korean art world to illuminate the work of veteran artist Kim Yong-ik. Following a major retrospective at Ilmin Museum of Art (September 1 to November 6), a solo exhibition of Kim’s works is now on display at Kukje Gallery (November 22 to December 30). The solo exhibition featured some thirty paintings produced over the last two years, including works based on his famous polka-dot series. Through the “re-editing” of his earlier works, Kim continues to reflect on matters of aesthetics and the doing of art.

Thinner... and Thinner...

This year was a busy one for artist Kim Yong-Ik, also known as the “polka-dot artist,” with a major retrospective and a solo exhibition of new works held back to back. The retrospective, held at Ilmin Museum of Art(2016. 9. 1~11. 6)looked back at the path Kim has carved out over the last four decades, beginning in the ’70s, from modernism and Minjung art (or people’s art) to conceptual art and public art. It was a chance to see some of Kim’s major works and also consider the diversity of his pursuits thus far. The exhibition at Kukje Gallery,(2016. 11. 22~12. 30)on the other hand, focused on Kim’s newer works, introducing thirty pieces he produced during the last two years, and was described by organizers as an opportunity to examine the action-oriented qualities and tendencies of Korean art in the years following the Dansaekhwa, or Korean monochrome, movement. Considering the art sector’s present preoccupation with bringing post-Dansaekhwa Korean art to market, no doubt the exhibition of Kim’s new works will receive this kind of attention. Yet as the artist himself has disclosed, the new works are re-edits and reformulations of his well-known past works. This review will therefore explore briefly how these newer works are in fact a continuation of all that the artist has produced over the past forty years.

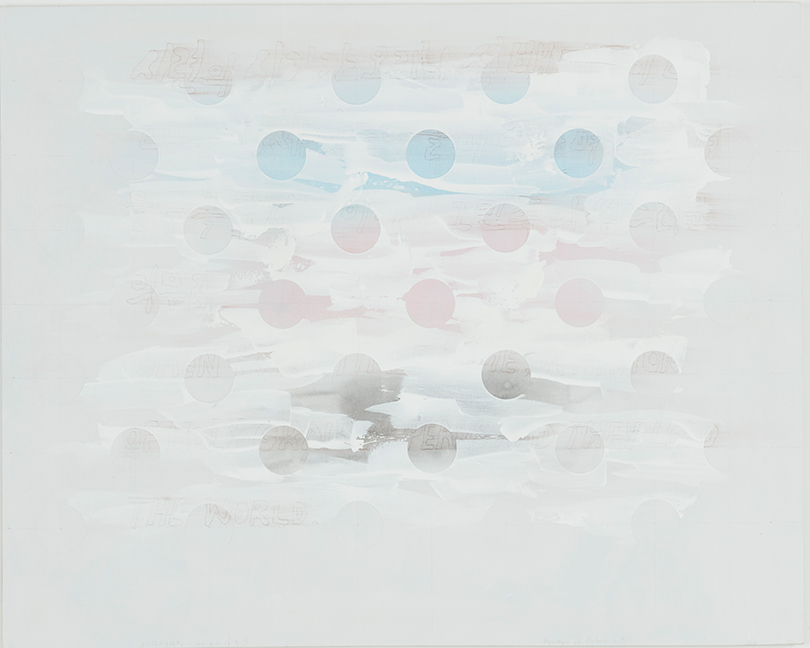

Kim Yong-Ik, ‘Apocalypse of Modernism #13’, 2016, Acrylic on Canvas, 130×162cm, Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery.

Kim Yong-Ik, ‘Apocalypse of Modernism #13’, 2016, Acrylic on Canvas, 130×162cm, Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery.

Apocalypse of Modernism

The Kukje Gallery exhibit featured five series of pieces, respectively titled ‘Apocalypse of Modernism,’ ‘‘In the Lingering Shadow’ of Lies,’ ‘Thinner... and Thinner...’ ‘After 20 Years,’ and ‘Utopia.’ The polka dots that Kim made such prolific use of in the ’90s are the basic element in each of the series, but the sketches and prints he has created for some time have also been transferred to the canvas, where they undergo the artist’s “editing.” Kim began producing the polka dot series, today regarded as his trademark, in the 1990s. The pieces consisted of repeating patterns of circles painted on the canvas over a lightly drawn grid, one circle over every intersection point. While they contained some elements of modern painting, namely flatness and the use of grids, a closer-up view would reveal small lettering, stains, and other marks by which, paradoxically, the artist seemed to deny the flawless surface aspired to in modern art.

Of the five series, ‘Apocalypse of Modernism’ seems to show the author’s intentions to subvert modern art and show the end of modernism as a way of life. In ‘Apocalypse of Modernism #13,‘ circles are spaced equidistantly apart on the canvas. Underneath them are faint traces of handwritten text. The first line, in Korean, can be translated as “A time of testing will come...” A white wash of color has been applied over the canvas, covering the text but leaving the grid of dots; in the light brushstrokes across the canvas, though the paint isn’t thick, the gesture of the artist is clearly visible. Through this gesture, the artist makes cracks in modern art and the refined aesthetic it espouses.

Left) Kim Yong-Ik, ‘Plane Object,’ 1977, airbrush on cloth, 200×370cm (approx.)

Left) Kim Yong-Ik, ‘Plane Object,’ 1977, airbrush on cloth, 200×370cm (approx.)Right) Exhibition view of Kim Yong-Ik’s Solo Exhibition, “Closer... Come Closer...” at Ilmin Museum of Art.

The modern art that Kim has in mind appears to be Dansaekhwa, the movement to which he belonged and as part of which he became widely regarded as the definitive modern artist. During this period, he was already showing signs of a conflicted attitude toward Dansaekhwa, specifically in his major works from the time, the ‘Plane Object’ series. These works were composed of pieces of cloth big enough to cover a wall, spattered with paint using an air brush, and installed in a way to make the spots of paint and the wrinkles in the cloth visible. At the time, explaining the proposition behind the series, Kim called it a statement of his intention to resolve the opposition between objects and images. Kim Yong-ik, “Resolving the Opposition between Objects and Images,” Gonggan (Space), November 1978 edition (volume 137). Quoted on p. 26 of the exhibition booklet for “Kim Yong-Ik: Closer... Come Closer...” (Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2016) 1) With this series, Kim was a regular participant in the “Ecole de Seoul” exhibitions organized by his teacher Park Seo-bo, from the first edition in 1975 to the eleventh in 1986. But as he saw how his teacher and his seniors in the art world stressed Oriental philosophies while firmly situated within the mainstream establishment, Kim began to agonize about what “doing” art looked like, and he gradually turned his attention to other streams in the field. At one point, he outlined what he believed constituted a “good” work of art, according to ideas he’d arrived at while working on the ‘Plane Object’ series. A good work of art was one that (1) required little power (labor) to make, (2) required little money to make, (3) required no special skills, meaning it could be made in the same way by anyone else, (4) was easy and convenient to move around, and (5) wouldn’t be significantly affected by wear and tear or even some damage. Yet Kim, admitting that his own works failed to satisfy his criteria, added that perhaps “anti-criteria” works, in their flouting of such criteria, could also be considered good works. Kim Yong-ik, ‘Untitled,’ February 1987. Quoted on p. 69 of the exhibition booklet for “Kim Yong-Ik: Closer...Come Closer...” (Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2016) 2) As an example of paradoxical “anti-criteria” pieces, he mentioned his work with plywood.

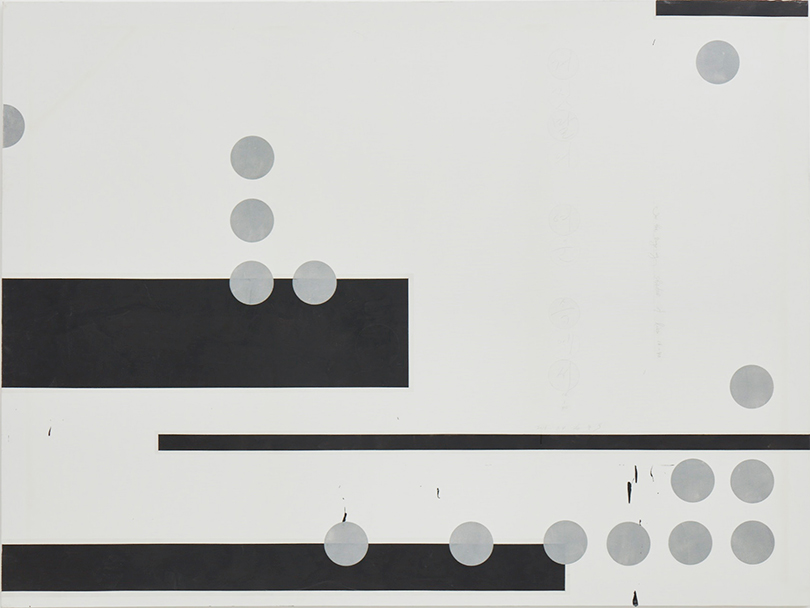

Nevertheless, Kim appears to have continued to aspire to the criteria he propounded, as the solo exhibition at Kukje Gallery has made clear. ‘Apocalypse of Modernism,’ ‘Thinner... and Thinner...,’ and virtually all of the presented works can be understood as manifestations of the artist’s efforts to create the “good works” he described. For the ‘Thinner... and Thinner...’ series, Kim worked on a different part of a canvas every day, a job that required considerable physical labor. By the end of this process he was able to achieve the effect of a very thin surface layer, hence the title of the series. It is quite evident that Kim now paints with a very light touch, even forgoing the underpainting step for some pieces. He has said before that this is a move to lay down the weightiness of his modernist self and move forward to the lightness of the deconstructed self, and also a message that the work in question has no serious meaning. The works in this recent exhibition are all characterized by bright colors and brushstrokes that create a light, thin texture. In this way, the artist “re-appropriates” the heavy, serious works of his past oeuvre, giving them a new lightness and thinness. In this way, the impressions of his older works are maintained while he turns his attention to a more lighthearted, jauntier practice, though making no pains to hide the contradictions between the two.

1) Kim Yong-ik, “Resolving the Opposition between Objects and Images,” Gonggan (Space), November 1978 edition (volume 137). Quoted on p. 26 of the exhibition booklet for “Kim Yong-Ik: Closer... Come Closer...” (Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2016)

2) Kim Yong-ik, ‘Untitled,’ General Financial Monthlly, February 1987. Quoted on p. 69 of the exhibition booklet for “Kim Yong-Ik: Closer...Come Closer...” (Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2016).

Kim Yong-ik, ‘Thinner... and Thinner... #16-83’, 2016, Mixed media on canvas, 91×117cm, Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery.

Kim Yong-ik, ‘Thinner... and Thinner... #16-83’, 2016, Mixed media on canvas, 91×117cm, Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery.

‘In the Lingering Shadow’ of Lies

“People don’t believe my words / Not even the praises in the reviews, not even the one asked to write the preface / They don’t believe my political opinions(…) The lies, their bulk, cloak the sky, and I go, my eyes / covered, to the bathroom and back / People don’t believe my words and I don’t believe my words / I’ve told no lies, but they were all lies / No apology can be offered for this wrongdoing...” These lines are from the poem “In the Lingering Shadow of Lies” by Kim Soo-young. Published only after the poet’s death, it is one of the artist’s favorite poems. He wrote some of the verses from this poem in minute lines on some of his new pieces. Penned in thin letters over washes of paint that seem to trickle down ever so lightly, the verses are full of meaning. The artist might have intended them to be just barely visible, little more than insignificant scribbles, but the profundity of what they say brings to mind another verse from a famous poem by Kim Soo-young, “The Great Root”: “Traditions, even dirty traditions, have value.” Even if they are the words of a poem, written, seemingly scribbled, in thin script, the weight of the ideas in them only seems more pronounced by the contrast of the lightly flowing paint.

Recently, the artist said the poem “The Great Root” had permeated his thoughts and resonated within him, without him needing any explanation. This writer cannot help but wonder how the artist was able to withstand the weight of this poem, this text. Kim has long considered writing and creating art as equally important. The artist himself, as prolific over the last forty years in writing as he has been in making art, has said that his role as an artist is that of “speaker.”3) Also an educator who has stressed to his students the importance of a creator’s thoughts and ethics, Kim has said he wishes to be one who makes use of his publicly authorized role within the established system of art to speak about the world. He accepts the system, which is why he doesn’t consider himself a radical, but at the same time, he maintains his suspicions about the system, which he says puts him in a position of self-contradiction. This is evident more in his writing than in his art works. The writings through which he conveys ambivalence about the system correspond to his post-1980s deliberations, following his exploration of Minjung art and public art, about the “doing” of art. It would be more accurate to say that Kim was somewhere along the boundary between Dansaekhwa and Minjung art rather than part of either group, but all the same, his deliberations translated not into self-oriented art concerned with authority but rather in projects that confronted the reality of the times and were carried out with an eye to engaging a popular audience. This is why it is important to note what he says about art, quoting cultural critic Lee Kangjin: “What literature (the arts) must do today is first imagine a future orientation for ‘politics,’ discrete from realpolitik and its preoccupations with ‘the political.’ Instead of being ‘done,’ with all of the limitations this entails, literature (the arts) must, through the free self, recover the capacity for anarchistic imagination, an absolute requirement of ‘politics.’”4) Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhornhas said, “I am concerned with doing my art politically—not making political art.5) What Kim aspires to, in his borrowing of the words of Lee Kangjin, seems to be close to what Hirschhorn seeks. And in connection to Kim Soo-young’s poem—“People don’t believe my words and I don’t believe my words / I’ve told no lies, but they were all lies”—this art will be paradoxical and thought-provoking, and in a sense, it will be all lies.

Kim Yong-Ik, ‘‘In the Lingering Shadow’ of Lies #16-40’, 2016, Mixed media on canvas, 194×259cm, Courtesy of the artist and Kukje GalleryImage provided by Kukje Gallery

Kim Yong-Ik, ‘‘In the Lingering Shadow’ of Lies #16-40’, 2016, Mixed media on canvas, 194×259cm, Courtesy of the artist and Kukje GalleryImage provided by Kukje Gallery

3) Gu Nayeon, Kim Yong-ik, Conversation at the 2013 Gyeonggi Creation Center Summer Academy, Gyeonggi Cultural Foundation (video link at http://www.ggcf.kr/archives/37054?cat=129)., http://www.ggcf.kr/archives/37050?cat=129).

4) Et al.

5) Thomas Hirschhorn, “Doing Art Politically: What does this mean?,” Critical Laboratory: The Writing of Thomas Hirschhorn, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013, pp. 72-76 (Kindle edition).

Lee Sunghui / Curator

Lee Sunghui is currently a curator for HITE Collection. She received her BFA in the Department of Industrial Design at KAIST, and a BFA and MFA in the Department of Art Theory from Korea National University of Arts. She is a recipient of the 2nd Artsonje Open Call.