“New Romance: art and the posthuman” is being held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia from June 30 to September 4, 2016. This exhibition was organized in collaboration with the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, where it was previously showcased in 2015. Co-curators Houngcheol Choi and Anna Davis, both based in new media art, centered the exhibition on experimental artworks that explore themes related to technology. While some of the works address themes specific to the artists’ respective countries, the exhibition as a whole concerns itself with a more globally common issue: what it means to be a human being in a world being rapidly changed by scientific, political, social and technical innovation. Participating artists are Rebecca Baumann, Ian Burns, Hayden Fowler, Siyon Jin, Airan Kang, Sanghyun Lee, Soyo Lee, Wade Marynowsky, Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho, Patricia Piccinini and Peter Hennessey, Kibong Rhee, Justin Shoulder, Giselle Stanborough, Stelarc and Nina Sellars, and Wonbin Yang.

How two countries created thier own mini-biennale

Art at its best gives us food for thought on the big issues of life on the planet. It always has, and presumably it always will bring our minds to bear upon what affects us as humans. It can also help to guide our paths in life. The rapid changes we are experiencing today bring new discoveries about ourselves, our bodies, our brains, how people can relate to each other, and how human and non-human life co-exist in the biosphere. Every day it seems we understand more how other lives, whether animal, bacteria or virus, are not all that different from ours. Who can ever forget seeing that documentary about the world inside the human gut, the rivalries and hierarchies of warring factions, the armies which protect our immune system against the forces that seek to harm it. And what of the incipient arrival of AI, that long-predicted force that may turn human lives upside down.

When artists are driven to explore this complexity through their image making and storytelling, and are allowed or encouraged to put their creativity out for public scrutiny in the grand spaces of art museums, the feedback loop of scientific, political, social and technical innovation enters a productive cycle. Australia and Korea were recently treated to an extraordinary philosophical/artistic adventure where an Australian and a Korean curator collaborated to bring together artists who address issues such as hybridity, random or deliberate mutation, biological/ecological collapse, emotional states, waste, artificial intelligence, sadness, the body transformed as surreal spectacle together with a modicum of comic relief.

Hayden Fowler, ‘Dark Ecology’, 2015, mixed media installation, image courtesy and © the artist

Hayden Fowler, ‘Dark Ecology’, 2015, mixed media installation, image courtesy and © the artist

Intersection between Korean and Australian art

Titled “New Romance: art and the posthuman”, with a nod and a wink to William Gibson’s Neuromancer(1984), this rigorously curated and presented bi-lateral exhibition was both a view of different preoccupations and of convergences.1) Australia and Korea are similarly placed geopolitically–as well as being geographically close–but most average citizens young enough not to remember the Korean War of the early 1950s know very little about each other’s countries and regard each other as more than a little exotic. A diplomatic and educational push in Australia in the 1990s to become familiar with countries in our neighbourhood saw pioneering exchange exhibitions and Australian artists embarking on residencies to Korea, but with changes in policy settings in the new century this receded to the personal friendships set up during those early leaps into the unknown.

During the 2011 Year of Friendship between Australia and Korea, the first of two bi-lateral exhibitions was created, and as with the current one, the collaborating institutions were the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia(MCA). As well as the conceptual gap between the countries Seoul and Sydney are very different–Seoul, over 2000 years old, with Imperial palaces wedged between solid swathes of apartments and offices, Sydney as an urban centre a mere 225 years old, with office blocks and British colonial buildings surrounded by sprawling suburbs, beaches, bushland and with a population half the size of Seoul. Australia and Korea are also notably different in their ethnic make-up, with historical origins and waves of migration determining Australia’s multi-culturalism as opposed to Korea’s privileging of the ancient lines of DNA.

1) I had a very keen interest in the Australia-Korea nexus and around the time of the curatorial discussions on “New Romance” I had independently started work on the 2015 special issue of “Artlink” magazine titled ‘KOREA: contemporary art now’, (also funded partly by the bilateral government agency the Australia Korea Foundation).

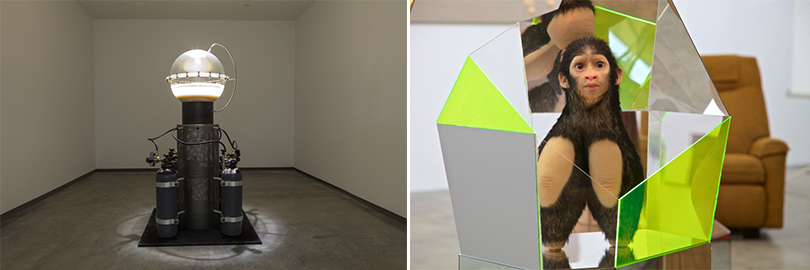

Left) Stelarc & Nina Sellars, 'Blender', 2005/2016, installation view, "New Romance", MCA, Australia, 2016, mixed media, image courtesy the artists and MCA, Australia © the artists, photo: Alex Davies.

Left) Stelarc & Nina Sellars, 'Blender', 2005/2016, installation view, "New Romance", MCA, Australia, 2016, mixed media, image courtesy the artists and MCA, Australia © the artists, photo: Alex Davies.Right) Patricia Piccinini & Peter Hennessey, ‘Alone with the gods’, 2016, installation view, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide, mixed media, image courtesy and © the artists

What did this mean for Inhye Kim and Glenn Barkly the curators of the first collaborative exhibition "Tell Me Tell Me: Australian and Korean Contemporary Art 1976–2011” and for Houngcheol Choi and Anna Davis who worked together on the second? The website of the MCA notes the historical basis of the first show, discovering the shared US and European art-historical movements over the 30-year span that it covered

“Tell Me Tell Me” took as its starting point the visit of Nam June Paik to Australia and the 1976 Biennale of Sydney, which included a number of important Korean artists and put these projects into the context of conceptual, post-object and technological art being done in both Korea and Australia, back in the 1970s and through to 2011. The core of the exhibition comprised a significant collection of historical works by important artists from both countries. It then explored the work of artists referencing recent art histories and influences such as Fluxus and the weight of Conceptualism.”2)

Two years later work started on “New Romance” with initial visits to Sydney and Seoul by the new curators. Neither Choi nor Davis had been to each other’s countries before or worked to any extent with artists from the other country. The premise for this show was to showcase new or recent work by living artists known for their experimental practice; the work was not necessarily drawn from existing collections and some was sourced directly from studios. Designed, however subtly, as a diplomatic strategy to use art to bring Koreans and Australians closer together, it is a tribute to skill and vision at directorial level that two such dynamic and imaginative curators were selected from the staff of the two museums and allowed to dream. Houngcheol Choi’s experience in new media, art/science and bio-art and Anna Davis’ in a wide range of practice across new media, were well matched. With language barriers, the different structures and policies of the two museums, infrequent face to face meetings between the two very busy curators, and the clock ticking for the first showing in Seoul for September 2015, it was clear by March that year when I met with Choi at the splendid new MMCA(whose vast corridors occupy as much space as the gallery spaces of most Australian art museums), that the task was both exciting and very challenging, not least because such a high proportion of the works they chose to show depend on technology. Strangely, the works that most closely match with the exhibition’s descriptor 'Art and the posthuman’, the sculptural pieces by Patricia Piccinini, were some of the very few pieces that you could view during a power cut.

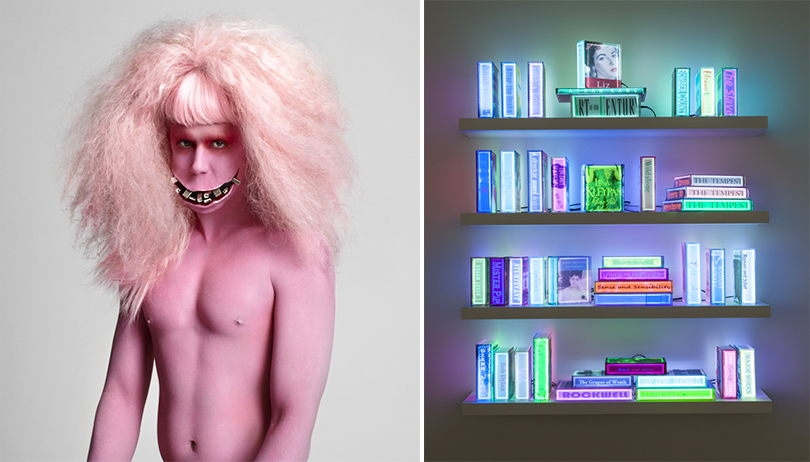

Left) Justin Shoulder, 'Pinky', 2014, type C photograph, photo: Jordan Graham

Left) Justin Shoulder, 'Pinky', 2014, type C photograph, photo: Jordan GrahamRight) Airan Kang, ‘Digital Book Project', 2016, installation view, "New Romance", MCA, 2016, LED lights, resin, 107×custom electronic books, image courtesy the artist and MCA, Australia, © the artist, photo: Alex Davies

What it means to be a human being today

Taken together, most of the works shown in “New Romance”(in its two slightly different iterations in Seoul and Sydney), related to what it already means to be a human being today. This is the world we live in where books are no longer real books but digital ciphers of a book, (eg. Airan Kang), where a dance is made visible by a series of LEDs attached to the dancer’s limbs(eg. Siyon Jin), where computers control great swathes of our lives(eg. Rebecca Baumann, Kibong Rhee and others) and where a gendered expression grief is a man’s head crying on a screen (eg. Seung Jung). Each piece connects with others to create a context for meanings that can be read into the whole. In looking at the natural world Soyo Lee gives a real life account of the vast Korean industry which turns out cactus plants in shades of bright red and yellow for an insatiable market. These unnaturally colored cactus cannot photosynthesise, so old-fashioned horticultural techniques are used to graft them onto an ordinary functionally green plant. And during the show there were workshops to show how it is done.

The Seoul iteration opened last September with a program of performances and workshops by Stelarc with his ‘Extended Arm’ a work that he has been developing in various versions since his 'Third Hand’ in 1980. His performance and commentary on the arm continues to engage and thrill audiences, even though prosthetics in 2016 are commonplace, proving that art/science works succeed not because they are outlandish or shocking but because they have other meanings. “A prosthesis not as a sign of lack, but rather a symptom of excess”. His latest work 'Blender’, with Nina Sellars, uses subcutaneous fat sucked out of the two artists’ bodies and combined in a large clear plastic bowl, a sort of cross between an incubator and a milk churn. The steampunk feel of this object with its gas cylinders, clunky hardware and unattractive yellow stuff conjures up current practices of getting rid of ‘unwanted’ fat in increasingly obscene ways.

Top) Wade Marynowsky, ‘Moonwalker’, installation view, "New Romance", MCA, Australia, 2016, steel, aluminium, motors, electronics, textiles, code, textiles: Sally Jackson, image courtesy the artist and MCA, Australia © the artist, photo: Alex Davies.

Top) Wade Marynowsky, ‘Moonwalker’, installation view, "New Romance", MCA, Australia, 2016, steel, aluminium, motors, electronics, textiles, code, textiles: Sally Jackson, image courtesy the artist and MCA, Australia © the artist, photo: Alex Davies.Bottom Left) Kibong Rhee, ‘Perpetual Snow’(detail), 2015, glass, silicon, aluminium, steel, marker pen, arduino system, image courtesy and © the artist.

Bottom Right) Wonbin Yang, ‘Umbra infractus’, 2012, from ‘Species series’, installation view, "New Romance", MCA, Australia, umbrella, electrical devices, image courtesy the artist and MCA, Australia © the artist, photo: Alex Davies.

A couple of robots courtesy of Wade Marynowsky mess with our minds. In ‘The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeois Robot 2’ we are approached by an oversized velvet hoop skirt sporting a long neck ending in a phallic shape; she sweeps around the space seemingly quoting Oscar Wilde at us. In his ‘ Moonwalker’ a pair of skeleton legs hang limply from a huge red velvet ball while at intervals its bony feet are induced to rise up on tiptoes. Michael Jackson would not necessarily have been amused. The insane 'Blender’ by Ian Burns is a set-up of old-style filament light bulbs that cast wobbly letters on the wall spelling out the words ‘oh so pretty’. Resembling a piece of bush engineering with a pile of magnifying glasses, it has lots of wiring, an electronic keyboard playing a snatch of an ABBA track- and of course a kitchen blender that joins in from time to time. How it manages to create a superbly poetic vision with all this is the genius of Burns.

One of the more disconcerting works was by Wonbin Yang. The urban detritus that is blown around the streets, such as a stained and crumpled piece of paper or one of those sad broken umbrellas now appears inside the gallery, using invisible robotics to make them shudder and move as if propelled by a gusty wind. Kibong Rhee’s poetic riff on what technology and data tries to do to help us understand natural forces, in this case snow, is a silicone forearm and hand holding a white marker pen performing the task of inscribing a small circle on the back of a gigantic sheet of glass over and over again until after many weeks the glass is almost a complete white-out.

And then there are the post-apocalyptic scenarios. In a greyscale theme park set-up Hayden Fowler has the cave-man of the future clothed in animal skins crawling out of a cave surrounded by white spheres and dead trees together with videos of anxious birds in dark lifeless bushes. Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho’s two-channel video shows two people trapped in the particular hell they are each destined to inhabit, a woman performing categorising tasks in a sterile laboratory-like space, an unkempt man doomed to scratch an existence in a ruined landscape.

In terms of the specifically post-human we enter the world of Patricia Piccinini. In Seoul there were a number of her astounding super-real silicone sculptures of human-animal hybrids, (whether products of genetic engineering or having evolved in response to a yet unknown future). They are sometimes shown living side by side with ordinary humans, often children. In Sydney, with Peter Hennessey, she makes an environment for a whole family or group of creatures, less realistic and with simpler adaptations such as multiple breasts, mouths, or other organs attached to cuddly rounded bodies resembling soft toys. These inhabit a grungy domestic set up, a DIY laboratory with plastic beakers sitting on a kitchen sink where it seems these creatures originate. They are domestic scale versions of her earlier more startling hybrids, ready to serve their makers by being docile and useful.

Soyo Lee, ‘Ornamental Cactus Design’, 2013–16, cacti, wood, plastic, digital prints, Courtesy the artist

Soyo Lee, ‘Ornamental Cactus Design’, 2013–16, cacti, wood, plastic, digital prints, Courtesy the artist

This exhibition brings together the work of a hugely accomplished group of artists and curators who are like-minded in their engagement with global cultural issues. Some of the works contain country-specific references, such as the cactus-grafting or Lee Sanghyun’s inventions around North Korean spectacle with Lady Gaga; Giselle Stanborough’s screen dating videos and Justin Shoulder’s queer performance works; in addition there are recognisable Aussie make-do and comic-endearment elements in the work of Ian Burns and Wade Marynowsky. Given the global context in which new media artists operate, although not all of them are able to afford to travel and work in other countries, themed shows curated across different countries tend to reveal more common elements than disparate ones. What is not common however, especially in our region, is cross-pollination of ideas at a personal level amongst these professionals. If recent expressions of xenophobia in many countries continue to increase, the activities of artists and scientists offer alternatives.

What next for Australia and Asia-based art projects? Will the Korea connections so bravely forged in “New Romance”, where artists were assisted to travel and participate in the install of the two shows, be taken up by organisations in Australia with or without the support of official diplomatic and trade agencies? Will those in Korea be inspired to bring shows to Australia, or set up partnerships?

Stephanie Britton / Founding Editor Artlink

Stephanie Britton AM is the founding Executive Editor of “Artlink” magazine, and has initiated and created many special issues themed on Asian contemporary art and culture which included forums and talks in China, Korea and Australia. Her most recent is the 2015 issue of “Artlink” titled ‘Korea: contemporary art now’. She is currently based in Byron Bay, New South Wales, pursing Asian-Australian publishing projects.