Art Spectrum is a biennial exhibition organized by Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, to discover and promote emerging Korean artists. Ten artists/art groups are selected to participate on the recommendation of Leeum curators as well as outside curators; one among them receives the Art Spectrum Award. In the broad spectrum of works unconstrained by genre or theme, visitors can make out the currents of contemporary Korean art. Art Spectrum 2016, which opened on May 12, features the works of Young Eun Kim, Kelvin Kyung Kun Park, Minha Park, Jungki Beak, Dong-il An, Okin Collective, Optical Race, Hoin Lee, Jane Jin Kaisen, and Haeri Choi. The exhibition will run till August 7.

(Doing) Art in the More Uncertain Present

From its inception at Ho-Am Art Museum to its relocation to the Leeum, the biennial exhibition “Art Spectrum” has for six seasons illuminated the works of young artists chosen by in-house and outside curators. At a time when most of the programs providing direct support to young artists are being downsized, “Art Spectrum” offers a platform of compelling scope. Museumgoers, too, find there’s something immensely satisfying about seeing the painstaking labors of young artists displayed in a major institution. With “Art Spectrum” attracting wider interest, the official announcement of selected artists comes preceded by a flurry of predictions as to who will be picked, and who, since the introduction of the Art Spectrum Award last season, will take home the prize.

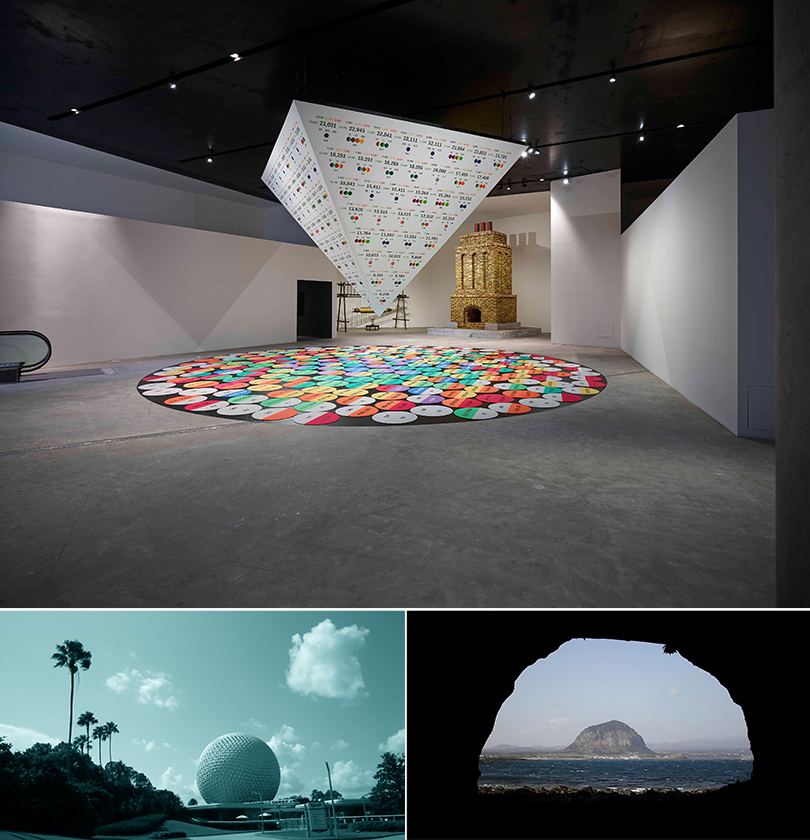

Top) Art Spectrum 2016 Exhibition view (Front: Optical Race, Family Planning, 2016, Back: Jungki Baek, Akhaedokdan, 2016)

Top) Art Spectrum 2016 Exhibition view (Front: Optical Race, Family Planning, 2016, Back: Jungki Baek, Akhaedokdan, 2016)Bottom left) Minha Park, Timespace, 2016, Single channel video, 23:23 Right) Jane Jin Kaisen, Reiterations of Dissent, 2011/2016, 8 channel video installation, Color/B&W, sound, 77:26

Aside from having undergone the same selection process, the works of the ten artists/groups participating in “Art Spectrum 2016” appear to have little else in common. Much deliberation likely went into ensuring the representation of a diverse range of media, and each work sets itself clearly apart in choice of themes and methodology. The exhibition’s premise—of contemporary art as a diverse spectrum—becomes thus readily apparent. In mood and tone, “Art Spectrum 2016” shows a marked divergence from the exhibition of 2014, where many a statement and story lodged overt criticisms of social institutions. Not that this year’s artists aren’t interested in social issues; rather, their methods of constructing and reconstructing the present issues, and the media they use, vary widely. Perhaps this is why the exhibition left me with an initial impression close to déjà vu, close to the feeling of having completed an online browsing spree. With a click of the play button on iTunes, my journey began. I was led through an assemblage of visual representations of Korea today, through Hell Joseon1) as rendered in various forms of documentation that, unable to keep up with the timelines of social media, are on the brink of vanishing. Situations at once familiar and foreign unfolded without end as I floated through that stateless space, where events of history and problems of ideology became entangled with past and present, all to the soundtrack of a fake music video.

1)“Hell Joseon” is an expression that equates modern-day Korean society, with its demanding workplace culture and lack of opportunities for young people, to a living hell.

The possibilities of visibility

I observed multiple attempts at experimentation with form, efforts to give visibility to the ideas that comprise reality, particularly as experienced in present-day Korean society—notions of the artist’s mode of existence, of marriage in the Echo Boom generation2) , and immaterial things like sound. Though concerned primarily with questions of form and technique, such attempts assert that art as it is “done” today does not stay within the bounds of prior convention; neither is it possible to explain or interpret what is created within the framework of the past. The works of Okin Collective, Young Eun Kim, and Optical Race make this especially clear.

2) The “Echo Boom Generation,” or “Echo Boomers,” refers loosely to the generation that came after the Baby Boom generation (the generation born in the years after the Korean War) and is thus considered that earlier generation’s “echo.”

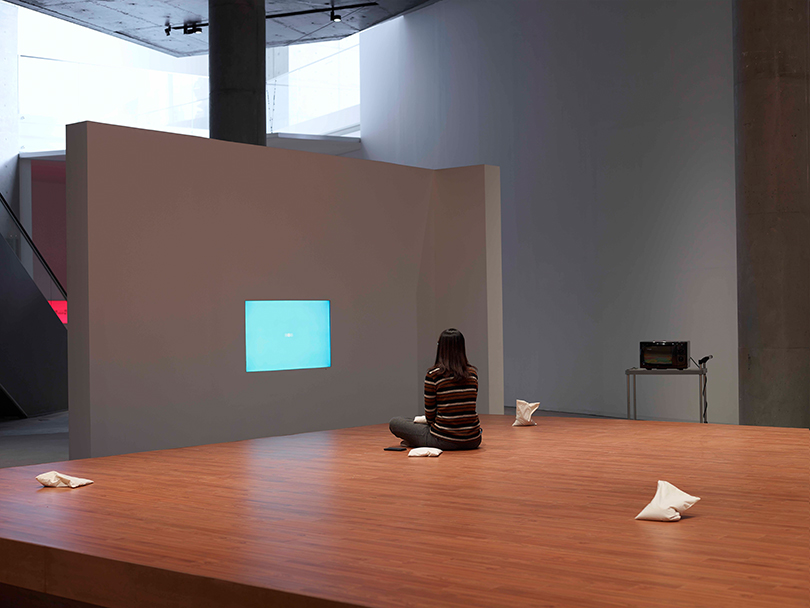

Okin Collective has persistently called into question how the artist’s mode of existence in modern society, in all of its instability, is romanticized and abstractified under the very guise of making art. The group’s latest work, “Art Spectral,” explores the specific considerations involved both in creating art and becoming an artist. “Art Spectral” is a situational piece, designed around the keywords “vanishing” and “phantom,” realized in a space furnished with a wooden floor, single-channel video, sound, and books. The intention and language behind the work are conveyed in concrete form through various writings commissioned by the group, which the viewer is invited to experience firsthand. Before addressing what is created, this production examines the how—the process by which art is made—turning the act of art (and the act of being an artist) into a performance. Merely by being present, the viewer fulfills a unique role in this space.

Above) Okin Collective, Art Spectral, 2016, Wooden floor, books, sound, single channel video, microwave, rice pillows, Dimensions variable ⓟ Hyeonsu KIM

Above) Okin Collective, Art Spectral, 2016, Wooden floor, books, sound, single channel video, microwave, rice pillows, Dimensions variable ⓟ Hyeonsu KIM

Young Eun Kim’s “$1’s Worth” is an experiment of sorts, whereby the artist seeks to reproduce sound in material form through the medium of the digital audio file (which, being a product, is assigned within the market a particular monetary value). Here, Kim incorporates her distinctive interest in language, identifying the basic elements of a song: “length,” or playtime; “height,” referring to pitch; and “width,” as measured in wavelengths of sound. She then proceeds to repurpose a unit of music worth a dollar and twenty-nine cents, reducing its value to a dollar. Kim’s experiment cuts music into segments like slices of tofu, trimming and snipping as if cutting up paper. Capital, in the form of a dollar’s worth of a value, is the basis for her arithmetic, which effectively transforms existing music into something more incongruous and stilted—choppy songs and thinned-out sounds. It’s doubtful whether depreciation in market value or alteration of sound is really all this reduction in monetary value indicates.

“Family Planning,” designed by Optical Race, uses infographics to present statistical data produced through research, analysis, arrangement, processing, and reorganization. Using statistical information, the work visualizes not only the reality that is being experienced by the majority of people in Korea, but also one that has yet to arrive. Thus, this social reality is given material form, but the artists don’t seem particularly interested in espousing their personal attitudes or views on the issue. In a sense, at a time when the standard definition of family is breaking down, and marriage itself is becoming an impossibility, the norms of family structure, home ownership, and marriage referenced by this work may very well be things that do not, or cannot, operate any longer. Moreover, a final conclusion as regards this matter can only take complete shape through the experience of the viewer, who, responding to the instructions of the work, searches for the diagram that corresponds to his or her economic index.

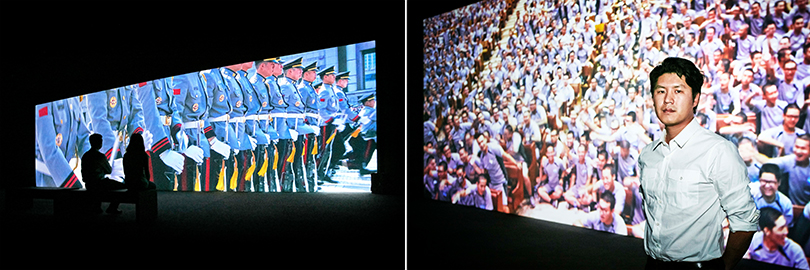

Left) Kelvin Kyung Kun Park, 'ARMY: 600,000 Portraits' Installation view

Left) Kelvin Kyung Kun Park, 'ARMY: 600,000 Portraits' Installation viewRight) Winner of 2016 Art Spectrum Award Kelvin Kyung Kun Park

‘ARMY: 600,000 Portraits,’ by Kelvin Kyung Kun Park, also addresses a thorny issue in Korean society, but here too the artist’s intentions and thematic concerns are not made explicit. This quality echoes Park’s earlier work ‘A Dream of Iron,’ which was fixated wholly on the “objecthood” of iron. Employing various visual clues, “Portraits” constructs an absorbing multi-layered view of Korean society within a tightly packed frame. For seventeen minutes, the video plays on repeat, centering on the image of the closed door, and it is more than the giant screen that draws the viewer in. The riveting scene of an honor guard lining up in formation, for example, reverts to a scene inside the training camp chapel. When the congregation replicates en masse the motions being performed onstage by an all-girl Christian entertainer group, the viewer feels a mix of emotions—amusement, embarrassment, and discomfort, among others.

Another work that generates similar emotional dynamics is Hoin Lee’s “Crossing.” Lee’s canvases, despite appearing to depict ordinary, everyday scenes, suggest a murky sense of something amiss. Lotte World Tower, the National Assembly building, a bridge over the Han River, a city shrouded in micro-particle dust—these landscapes rouse the imagination in a manner intimated by the work’s title. Present in every canvas are flashes of light (referred to in the title of Lee’s 2015 work “Flash”) that serve as evidence confirming the viewer’s suspicions. In contrast to depictions of light and darkness in traditional painting, renderings of artificial light and the reflections and shadows it creates constitute a self-reflection of the artist. Like an incantation, this light summons the memories that have been and will continue to be forgotten, blotted out by Korean society and its tremendous capacity to expunge.

Above) Hoin Lee, Crossing, 2016, Oil on canvas, 227 x 181.6cm

Above) Hoin Lee, Crossing, 2016, Oil on canvas, 227 x 181.6cm

Between impatience and indifference

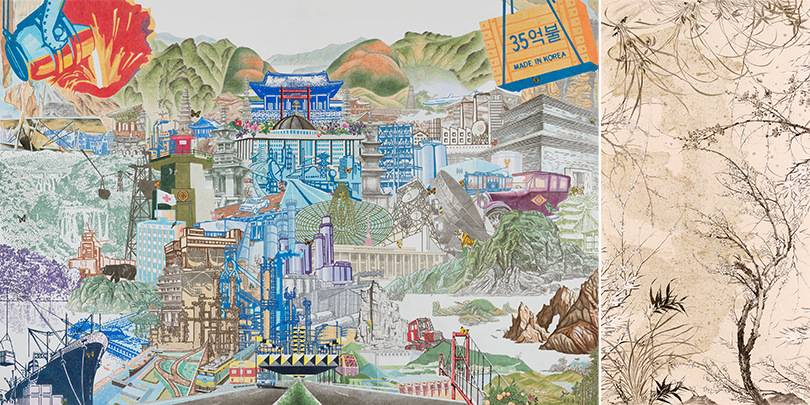

For today’s generation, it’s perhaps a given that inhabiting the same space and time does not equate to experiencing life in the same way. Where the above works scrutinize aspects of “real life” in Hell Joseon, other artists synthesize the materials and information they have collected to construct imagined worlds of space and time. In ‘Remixing Timespace,’ Minha Park utilizes a variety of video footage to create a film that rearranges the dynamic attitudes people have about space exploration. Jungki Baek connects traditional rain rites with various technical equipment of his own design in ‘Akhaedokdan,’ creating a memorial that blends incantation and science. The ink paintings of Haeri Choi also reinterpret traditional painting through a modern lens, modeling an intrusion of the present into the past that is also prominent in the work of Dong-il An (‘Our Land of Korea’). Jane Jin Kaisen, who has long pursued critical inquiries into the Jeju Uprising, looks at individual and collective historical memory in Korean society. Her ‘Reiterations of Dissent,’ in addition to showing how such memory is erased within a society still very much shaped by ethnic and state-based nationalism and Cold War ideologies, raises issues of enduring pertinence.

Left) Dong-il An, Our Land of Korea, 2016, Color on Korean paper, 290.9 x 197㎝

Left) Dong-il An, Our Land of Korea, 2016, Color on Korean paper, 290.9 x 197㎝Right) Haeri Choi, Bamboo in Snow, Plum Blossom in Summer, Orchid in the Cold in Zero Gravity Seen from All Directions 2016, Ink on Korean paper, gold pigment, 210 x 117 x 4㎝

Most of the works covered briefly here demonstrate a high level of completeness, having been produced in the vein of much contemporary art, using an aggregation of sophisticated, specialized, research-based knowledge. Such impeccable craftsmanship, rather than creating a space where the viewer can enter into a work, may be construed as an attempt to demand or coax a certain interpretation and understanding of the artist’s reasoning. Young artists today, seeking to shift artistic experimentation and history out of the predictable and into new forms, ingest a mixed diet. All manner of information is consumed and then processed to produce an endless stream of ideas, propositions, and conditions. A kind of hybridized identity emerges from this process, one that is defined not only by use of media and methodology but also everything else that accompanies the act of doing art, including the artist’s multiple roles and concerns as well as overall changes in his or her positionality. It is because the inspiration behind clever ideas or moments of creative stimulation cannot be identified with certainty that Maurice Blanchot said artists should position themselves somewhere between impatience and indifference. The introduction to Art Spectrum 2016 speaks of “possibility, the future, and the next step.” In considering this forward-looking proposition, I discover, paradoxically, a greater preoccupation with the present, a time more uncertain than ever. The Korean word for future is originally rendered in two Chinese characters that together mean “does not come.” This may be the more accurate definition of the concept of the future (Jeong Hee Jin). With the present evading our grasp and our comprehension, it is difficult to imagine something beyond it. Thus the “doing” of art today looks not at tomorrow in its nonexistence but at today; the things of the present become the substance of both art and artmaking, as well as the continued progress of the same.

Eunbi Jo / Independent Curator

Eunbi Jo has been a curator at KT&G SangsangMadang Gallery as well as Art Space Pool. Her past exhibits include The Forces Behind (2012, co-curated, Doosan Gallery), A House Yet Unknown (2013, Art Space Pool) and Floating and Sinking (2015, Gallery Factory). She is currently a researcher in residence at the SeMA Nanji Residency.