Constantly reinventing his work and practice, Kim Yong Ik stages an elegantly restrained minimalist exhibition at Tina Kim Gallery – here is our review.

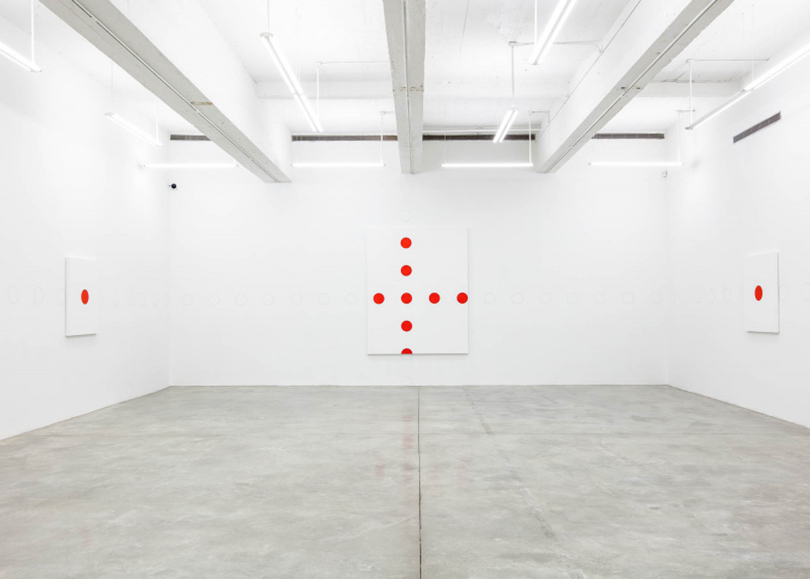

Installation View of 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》 at TIna Kim Gallery, New York.

Kim Yong-Ik never fails to surprise his audience. In his second solo exhibition, 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》(2019) at Tina Kim Gallery, Kim’s signature polka dots are unexpectedly pristine and unsullied. For Kim the dots are a part of his lifelong subversion of art making—often appearing smeared, soiled, and scribbled upon in his earlier work—in keeping with his anti-art aesthetic. A nonconformist from the get go, Kim’s art developed in defiance of the minimalist Dansaekhwa movement of the 70s and later the left leaning Minjung art or “people’s art,” of the 80s in South Korea.

Installation View of 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》 at TIna Kim Gallery, New York.

Kim’s iconic dots first materialized in the 90s as non-painterly rubber circles fixed to the canvas, and later progressed into what he termed as “meaningless grids.” Large dots made in geometric formats that resemble the repetitive nature of monochrome Dansaekhwa paintings are in fact representative of Kim’s belief that anyone can make art. His effort to upend the hallowed institutions of the art world and democratize art making came with hand written notes on the back of his works and his practice of continually adding layers to his paintings that questioned whether a work of art is ever complete. This idea of incompletion is furthered in his site specific installation in New York. Here black and red dots presented in adjacent rooms appear to be one continuous work. Occupying two large rooms in the spacious storefront gallery, precise graphite circles drawn in a horizontal line directly on the wall slide seamlessly onto accompanying white canvases. There they might be painted in half moons on some canvases or full circles as a part of a grid on others. Painted red and black circles also appear at random on the walls alongside empty canvases. In the second room, a large unpainted primed canvass hangs high in a corner just below the ceiling, while a second one is placed diagonally across the room on the floor.

Installation View of 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》 at TIna Kim Gallery, New York.

In keeping with his idea of disrupting the tradition of presenting completed works, the graphite circles, visible only up close, look like outlines of a larger unfinished piece. Half filled circles suggest the beginning of a work. Even the empty canvases anticipate some sort of intervention. Much like Dansaekhwa paintings that are essentially considered incomplete and require the viewer’s imagination to complete them, here too it seems incumbent upon the viewer to conceive the finished project. The entire framework of 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》, which is by turns spirited, whimsical, and captivating keeps raising the question of when in fact does one consider a work finished. In an interview with Ocula Magazine Kim discusses his inspiration from the Japanese Mono-ha movement, which stresses the importance to leave things as they are, and go with the flow of nature. His spare geometric shapes not only adhere to this notion of minimal intervention, but also parse his belief that art making does not introduce anything new. For Kim contemporary art is merely regurgitation of old forms, in which artists appropriate and rearrange existing works. In assessing his own practice, Kim believes that akin to an editor he constantly alters and mines his forty-year oeuvre.

Installation View of 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》 at TIna Kim Gallery, New York.

But there is something more compelling about this installation. I was drawn to its calm Dansaekhwa like effect. Kim’s re-appropriation of his circular grid in its repetitive seemingly random but ordered system evokes the meditative stillness of the very movement he revolted against. The stark spacious white cube fitted with a pattern drawn with mathematical precision creates its own aesthetic. There is an inherent beauty in the sparseness of the work. Even though there is much to be said for the power of his earlier stained canvases, which flagrantly challenged and disavowed traditional practices, Kim’s latter genesis, as it were, is refreshing. The sound and the fury of the past have subsided. Instead, the entire installation encompassing paintings that seem finished and never started at the same time offers the beginning and end of a line. The onset is the outcome and vice versa. As life’s cyclical nature became more and more evident to me, I realized that perhaps I was in tune with Kim’s effort to internalize the aesthetic of Korean spirituality deeply embedded in the principle of going with the flow.

Installation View of 《Speaking of Latter Genesis》 at TIna Kim Gallery, New York.

About the Artist

Kim Yong-Ik was born in Seoul in 1947 and graduated from Hongik University in 1980 with an MFA in Painting. He served as a professor of painting at the Arts and Design College in Gachon University (former Kyungwon University) from 1991 to 2012. In 1999, Kim co-established Art Space Pool (formerly Alternative Space Pool), one of the first alternative art spaces in Korea, and served as its representative member from 2004 to 2006. A committed critic, writer, and artist for the past four decades, Kim has been a vital voice in the Korean art scene, working in various contexts including Minjung art, land art, and public art, and continuously questioning his practice and art’s role in the ongoing modernization of Korean society. Kim’s work has garnered increasing attention from international audiences following his successful retrospectives at Ilmin Museum of Art (2016) as well as Spike Island, Bristol and Korean Cultural Centre UK, London (2017).

Kim Yong-Ik has held solo exhibitions at numerous institutions including 《I Believe My Works Are Still Valid》, Spike Island, Bristol, and Korean Cultural Centre UK, London (2017), 《Closer… Come Closer…》, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul (2016), 《Timidly Resisting the No-Pain-Civilization》, Art Space Pool, Seoul (2011), and Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul (1997).

Selected group exhibitions include 《Flatland》, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul (2018), the 5th Yokohama Triennale (2014), 《SeMA Gold 2012: Hidden Track》 at Seoul Museum of Art (2012), 《Nature and Peace》, Geumgang Nature Art Biennale (2010), 《After the Grid》, Busan Museum of Art (former Busan Museum of Modern Art; 2002), The 1st Korean Young Artists Biennial, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (1981), the 13th São Paulo Art Biennial (1975), and a series of Independent exhibitions at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art from 1974 to 1979.

His works are in the permanent collections of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea; Busan Museum of Art; Seoul Museum of Art; Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art; Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles among many others.

※ Click to Read the Full Article: https://www.cobosocial.com/dossiers/kim-yong-ik-speaking-to-a-latter-genesis/

※ This article was originally published in CoBo Social(https://www.cobosocial.com) on 11 JUN 2019 and reposted under authority of a partnership between KAMS and CoBo Social.

Bansie Vasvani

Bansie Vasvani is a curator and art critic with a focus on Asian and other non-Western art practices. She investigates contemporary art that mines issues of cultural identity, politics, immigration, and the commingling of varied cultural influences. Bansie travels frequently to Asia to study, research, and write critically. Currently she is working on showcasing art from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan and India at several institutions.

Her work has appeared in Hyperallergic, ArtAsiaPacific, Art Review Asia, Artnet news, Art21 Magazine, Brooklyn Rail, Sculpture Magazine, Daily Serving, Aesthetica Magazine, and Modern Art Asia amongst many other publications.

Bansie has a BA in English literature, Bombay University; an MA in English and American Literature, Northeastern University; ABD (all but dissertation) in English and American Literature, CUNY Graduate Center; and an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art History, Christies Education, New York where she earned the Best Student Award.