Features / Review

Imagine the art of an age that would coexist with artificial intelligence

posted 01 Jan 2021

Artificial intelligence is beginning to affect multiple realms of our lives, and its influence on the field of art cannot be underestimated. This influence and its symptoms can be felt at the Daejeon Biennale 2020. Under the title “《A.I., Sunshine Misses Windows》, this biennale held in Daejeon, Korea, seeks to integrate science and art to propose how artificial intelligence, which is at the center of the world’s growing attention, can be melded with or seen as art.

YANG Minha, 〈The listed words and the fragmented meanings〉, 2016, generative art, Image Provided by Daejeon Museum of Art

Daejeon Biennale 2020: A.I., Sunshine Misses Windows

9.8-12.6 Daejeon Museum of Art

The title of the biennale, which embodies a literary paradox, is from the eponymous book of poems written by Xiaoice, an AI system developed by Microsoft Asia in 2017. This publication consists of 139 poems written by the system after 100 hours of self-learning thousands of poems written by 519 modern poets since 1920. The fact that Xiaoice’s poems contain intrinsically human emotions attests to the fact that artificial intelligence has virtually entered the sphere of artistic expression. With an online opening held on September 8, the Daejeon Biennale 2020 received visitors until December 6 at the Daejeon Museum of Art and the KAIST Vision Hall. Amidst the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, 17 artists from six countries partook in this event to offer their interpretations of the relationship between artificial intelligence and art, using the four keywords: cognition, attitude, error, and tool.

A.I.-dentity: AI + Art, Artificial Creation and Human Cognition

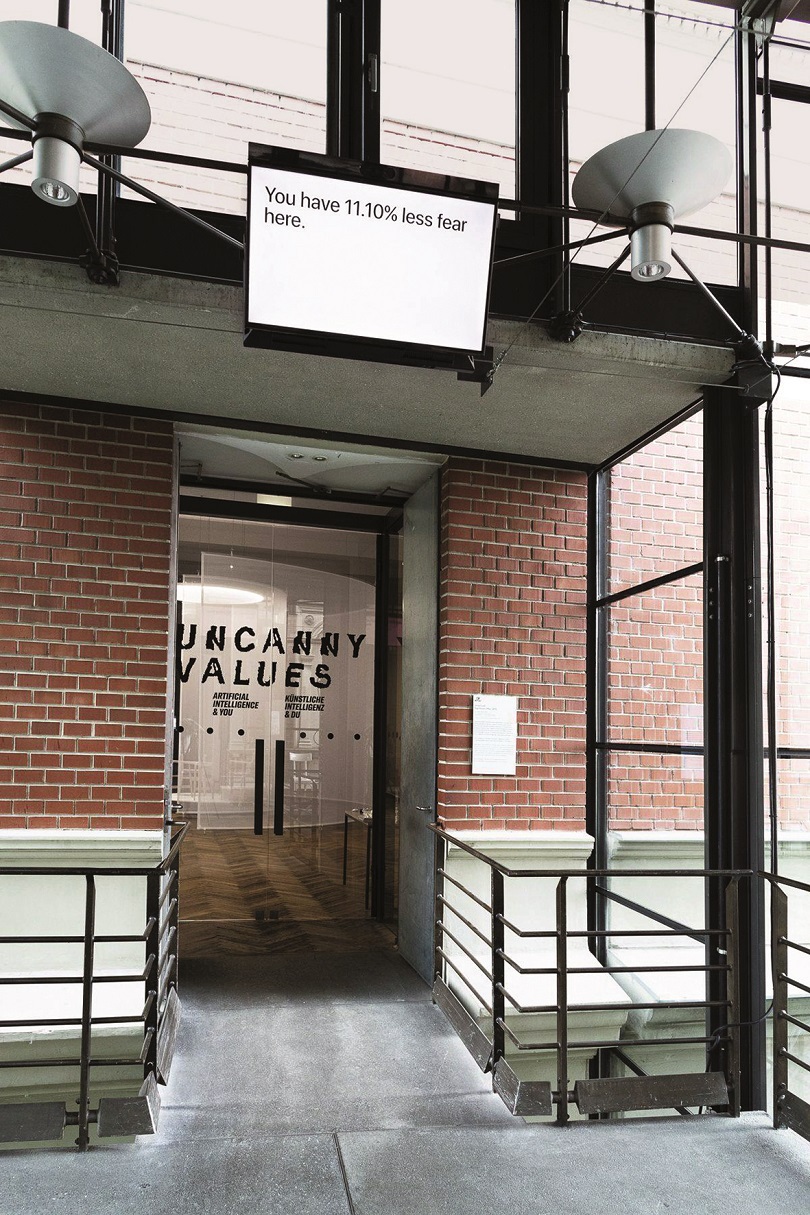

Applied widely across various realms, artificial intelligence enables facial recognition as well as identification and the analysis of patterns in a sea of information. Various mechanical learning methods have been devised for artificial intelligence to be able to detect truth from fabrications beyond the capacity of human judgment. Jonas Lund’s 〈Significant Other〉 (2019) at the exhibition’s entrance consists of two dual-screen-and-camera installations that register and compare the emotional states of audience members and synthesizes the results into text using Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) that connect the two artificial devices. Confronting unexpected information like “You are 22% more happy,” viewers can experience a moment of uncanniness in which artificial intelligence engages with them. A similar experience is offered by 〈My Artificial Muse〉 (2017) co-produced by Mario Klingemann, Albert Barqué-Duran, and Marc Marzenit. A process by which artificial intelligence creates a muse, a human source of artistic inspiration, and guides the rest of the production of an artwork proposes a new artistic mode to replace the conventional. In contrast, Shinseungback and Kimyonghun have a different take on artificial intelligence-based judgment. For their project 〈Nonfacial Portrait〉 (2018-2019), the duo commissioned painters to produce portraits under the condition that “artificial intelligence should not be able to identify a face from the finished portrait.” Producing something agreeable as a portrait by human judgment but unidentifiable by artificial intelligence rendered a tricky task. Nevertheless, works that met the criteria were ultimately produced to serve as indicators of the cognitive gap between humans and artificial intelligence.

YEOM Jihye 〈Future Fever〉, 2018, 2 channel video installation, 15min, Commissioned by MMCA. Image Provided by Daejeon Museum of Art

A.I.-ttitude: When Artificial Intelligence Becomes Attitude

Ever since AlphaGo, many have developed a nebulous fear that humankind may one day be dominated by artificial intelligence. With the technology in its nascent stage, however, some believe that it is way too early for such fear because there are enough opportunities and time to improve technology and prevent such a scenario. The biennale features works that utilize artificial intelligence as an artistic attitude.

teamVOID’s 〈Super Smart Machine〉 (2020) explores the phenomenon of technological excess through a series of artificial intelligence devices—specifically, speakers and a robot arm. When viewers flip the switch in front of them, the first smart speaker gives an order to the second, and the second passes it onto the third, and so on. The robot arm at the end of the order chain makes an elaborate mechanical movement to merely turn on a lightbulb. Meanwhile, Kelvin Kyung Kun Park’s 〈1.6 sec〉 (2016) explores the impact of machines on real life. The 1.6 second in the title refers to the shortened production time that results from robotizing a portion of a car assembly line in an automobile factory. With the introduction of a robot that executes a task in a shorter amount of time, the laborers formerly in its position lose their jobs. This work highlights that while mechanical advancements and the introduction of robots to factories speed up production and breathe new life into industries, there are people being edged out in the process. Hito Steyerl’s 〈The City of Broken Windows〉 (2018) and 〈Unbroken Windows〉 (2018) illuminate similar aspects but guide viewers toward a solution. The former is a video that captures windows being broken, a direct reference to the “Broken Windows” theory that dictates that the symptoms of small infractions such as broken windows create environmental conditions for more serious crimes. On the other side is the latter work, a video capturing the act of painting and installing unbreakable windows made of panels onto abandoned houses in an underdeveloped neighborhood. In 〈Remains〉 (2018), a series of inkjet prints of natural landscapes, Qualoya uses high-precision laser scanners to capture natural landscapes at extremely high resolutions and prints these complex digital renderings on large-format archival paper to present them as a new form of landscape that blurs the boundary between actual and artificially reproduced landscapes. Yeom Jihye takes a step further with 〈Future Fever〉 (2018), visualizing a grim future-to-come through a three-dimensional video installation.

Jonas Lund, 〈Significant Other〉, 2019, interactive media installation, Co-commissioned by Gluon and Televic. Image Provided by Daejeon Museum of Art

A.I.-though: Errors in Décalcomanie

Despite various attempts and advancements, artificial intelligence proves loopholed once it deviates—if only slightly—from its learned territory. More importantly, it harbors the very same biases prevalent in human society in collecting and judging data. Theresa Reimann-Dubbers’s 〈Room with View〉 (2020), an LCD screen installation reminiscent of a religious triptych, uses images obscured by opaque filters to metaphorize the bias and nontransparency inherent in artificial intelligence. In resistance to artificial intelligence’s poor recognition of race and gender beyond the figure of the white male, Zach Blas produced 〈Facial Weaponization Suite〉 (2012–2014), a series of amorphous masks undetectable by the facial recognition system. The masks, made of colors and forms unrecognizable by artificial intelligence, criticize the inequality in human society. This bias is more explicitly revealed by 〈The Listed Words and the Fragmentized Meanings〉 (2016), in which machines that have learned the languages of scientists, philosophers, and technical writers who brood over this failure in artificial intelligence end up disgorging indecipherable sentences. Furthermore, Park Earl’s 〈Machines on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown〉 introduces machines as subjects of neurotic symptoms experienced by humans, programming robots with rational algorithms that induce extremely irrational behaviors that mimic obsessive and compulsive behaviors found in humans. In response, Kim Hyungjoong’s 〈A Printer〉 (2020) consisting of 12 video feedback modules materializes a simple mechanical device that self-generates geometric and organic visual forms without any intervention from a program.

Kelvin Kyung Kun Park, 〈1.6 sec〉, 2016, 2 channel video & audio installation. Image Provided by Daejeon Museum of Art

A.I.-gent: Tools for the Next Generation

Artificial intelligence serves as a new tool for humans in the spheres of both life and art. Artist Lee Joo-haeng, who is also a researcher at the Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI), exploits a digital print of lantana blossoms using the “Pixel Stack” technique, producing 16 different images by relocating the image’s colorful pixels. Produced by the same method, the 〈Line Grid〉 series departs from the question “Can a simple line segment be the catalyst of a complex pattern?” and uses different formulas and algorithms to form various visual patterns reminiscent of abstract paintings in which strictly geometric structures repeat themselves. The process is further complicated and modified through deep learning, and additional color elements are introduced to make up dynamic compositions. While Lee Joo-haeng lays out visual patterns on flat surfaces, 〈The Skin〉 (2019) by Lee Byungjoo, Kim Hyunchul, Hong Sanghwa, and Kim Seonghyun, members of the KAIST Interactive Media Lab (KIML), visualizes the reaction of a touch screen to the subject of contact. This work maximizes viewer interaction using a touchpad designed to take real-time measurements of the eight properties of contact: stiffness, Young’s modulus, static friction coefficient, kinetic friction coefficient, contact area, contact location, tangential force, and normal force. As seen, artificial intelligence will continue to be applied as a tool for artistic practices and viewer inclusion in more extensive and efficient ways.

KIM Hyungjoong 〈A Printer〉 2020 media installation, Sponsored by CNCITY foundation. Image Provided by Daejeon Museum of Art

Art in the Age of Coexistence with AI

Artificial intelligence has become our unavoidable present and future. It has penetrated our lives in both recognizable and unrecognizable ways. But its point of intersection with the art world is still small and the connection still relatively weak. This biennale introduces works by artists who have contemplated this very point. More time and effort may be needed for detailed directives and methodologies to be devised, but nevertheless, various industries including the art world are exploring and applying artificial intelligence as a new medium and in the process are taking a step closer to a new tomorrow, that is, an age of coexistence with artificial intelligence. At a time when non-contact has suddenly become an utmost priority, the Daejeon Biennale 2020 offers not only works to be experienced firsthand on site but also a virtual exhibition tour and artist talks online via the Daejeon Museum of Art’s YouTube channel for those who cannot visit in person. By adopting this approach, which competitively utilized by art museums across the globe, the biennale attempts to meld science and art as it proposes a new mode of exhibition that holds significance for Daejeon’s art.

LEE Joo-haeng, 〈Line Grid-Ambiguous Boundary〉, 2019, 180×180cm×1(EA), custom code, digital print. Image Provided by Daejeon Museum of Art

※ This article was originally published on the OCT 2020 issue of Public Art and is provided by the Korea Art Management Service under a content provision agreement with the magazine.

Heo Nayeong

CEO of 'Visual Arts Planning' In Heo Nayeong is actively involved in the art scene as a critic and exhibition and forum planner. With both a bachelor’s and a doctorate degree in art from Hongik University, Heo currently lectures at Mokwon University and Seoul Digital University as well as at public events. She has authored numerous publications including 『Monet』, 『A Picture Painted in Color』, and 『A Woman who Became a Painting』, and continues to write critiques and media contributions.