Installation artist, interior designer, art director, collector - Choi Jeong-hwa, an artist with multiple labels active in all fields of contemporary art, is holding a solo exhibition at Daegu Art Museum. Choi's works are renowned for their colorful brilliance and diversity; the Daegu exhibition is notable for being the first to present a comprehensive collection of his works in one single museum space. A variety of objets, everyday items, mass-produced industrial goods and collected garbage fills the exhibition space, exuding the aura of an artist whose work commonly features in biennales around the world and who is more active overseas than in his native Korea. Art talks offering various perspectives onto the exhibition and works within it through expert cross-critiques offer glimpses into Choi's solo Kabbala exhibition and the world of his work through the eyes of art critics or art historians.

A natural history of the present, by Choi Jeong-hwa

Ⅰ. Scenes from the exhibition

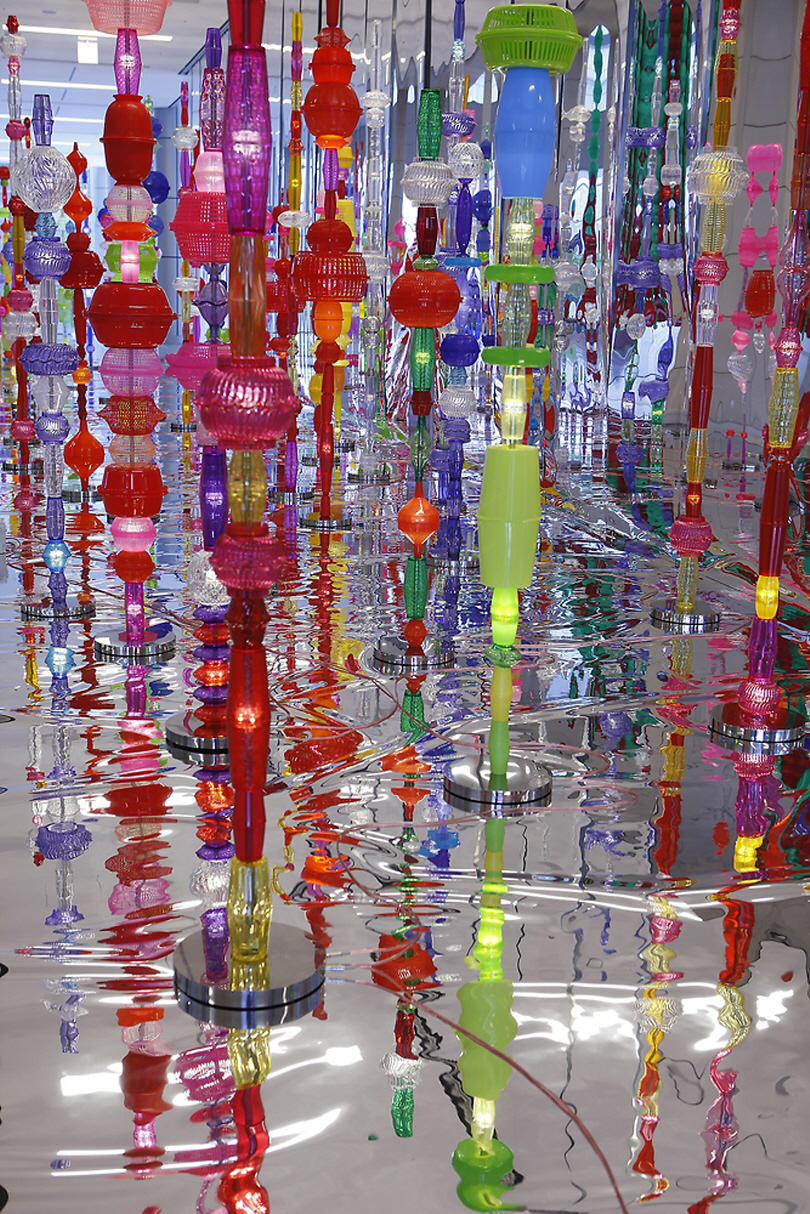

Choi Jeong-hwa_ Alchemy_Daegu Art Museum_2013_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_ Alchemy_Daegu Art Museum_2013_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa's Kabbala exhibition was held in 2013 at Daegu Art Museum. Motley collections of objects made from beads, LEDs and plastic filled the exhibition spaces – a veritable circus of alchemy. The whole show could be summarized in terms of sparkling, brilliant, glossy surfaces, while the cacophony of diffused reflections resembled the tunes of an accordion in a bustling marketplace at times; a well-crafted piece of chamber music at others.

The exhibition made use not only of the museum's allocated exhibition spaces, but of the huge central hall and the second- and third-floor corridors that open onto it. Choi installed his works in liminal spaces linking the here with the there. Works sat in corridors and passages that defied regulation; in places that were function more as verbs than as nouns. Perhaps this is why Choi's installations themselves are a kind of alchemy. The materials he uses are cheap industrial goods – discarded banners, household items, plastic wicker baskets, brightly colored bathhouse scrubbing flannels, trophies, plastic, cooking foil – or clones of them, or just plain junk. Never and nowhere does he insist on 100% purity. The mixed, the copied, the left-behind and various dregs come together to form his works. His exhibition, however, is miscellaneous yet clearly organized. Somewhere between these two aspects is the light that rebounds ad infinitum off each surface; we intervene in Choi's works by adding our own individual perspectives to the many light rays already at work. Kabbala is a story of the present and of surfaces, the patterns of the present. Perhaps, then, it is also a story of our own presents as they come face to face with these surfaces.

Choi Jeong-hwa_Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

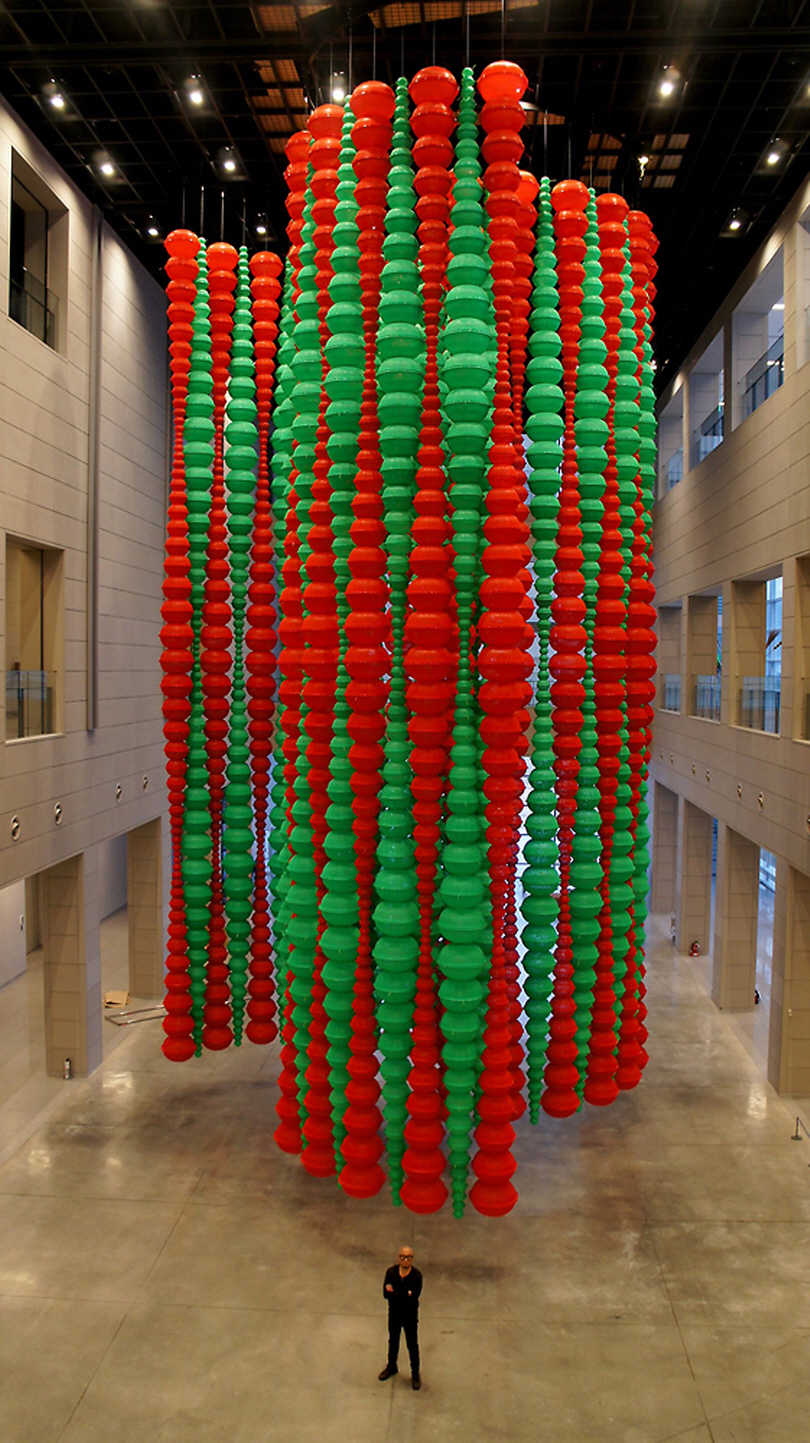

Choi Jeong-hwa_A Mountain of Burden_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_A Mountain of Burden_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

What is striking about the installation of this exhibition is the fact that the artist has provided us with an index of his works so far. Perhaps, as an artist, he has seized this museum exhibition as an opportunity to organize his oeuvre to date. Upon entering the museum, we are met with what seems like a catalogued list of the motifs associated with Choi: lined up in clear order on altars of assembled apple crates, the miscellany of glittering plastic pigs' heads, plastic ceremonial food replicas, lifelike plastic cabbages and giant daikon radishes, balloons, flowers and more provide an illustrated natural history of his work so far. These apple crates are instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever taken the slightest interest in art or culture in his or her local community; they thus play a symbolic role.

The use of these in the installation of artworks introduces communal memories and their accompanying intimacy to the content of the works. By summoning these memories into the here and the now, Choi breathes life into the ruins of the present. This point itself could be described as the artistic strategy that Choi has mastered: the way he actively draws the comfort and nostalgia aroused by the plastic, the crude colors and the tacky objects he uses into his works. This method makes full use of the sense of pleasure provided by the recurrence of memory. By showing us not only the clearly organized index of works based on the riot of colors, noise and movement that bounce in so many strange ways off the altars at the entrance to the museum, but also his strategy for using them, the artist provides us with a coherent and sincere overview of his entire oeuvre. Passing the introductory apple crate altars, we come to Choi's work Kabbala in the museum hall. Taking Kabbala as their centerpiece, organized rows of antiques, plastic objects and newly designed objects based on them occupy the corridors leading off from the hall on the second and third floors. The whole show is observed by Funny Game’s mannequin policemen; these imitation cops, who may or may not actually be doing anything, serve as joke-like signposts at various points throughout the venue. Such are the scenes that revolve around the exhibition's central work, Kabbala (variations on a plastic basket).

Choi Jeong-hwa_Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_Kabbala exhibition_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_Kabbala exhibition_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Ⅱ. Redeeming the present through the patterns

What, then is our present according to Choi Jeong-hwa? The usual notion that Choi tries to give a message of harmony between the natural and the artificial does not go quite far enough. Neither does the exhibition constitute some kind of border dispute between the realms of art and the everyday. As he himself has claimed, the artist's consistent hope is that art be akin to a vivid, living museum rather than a collection of fossils, that it remain fresh for as long as possible, and that it strike a chord with and bring pleasure to as many people as possible. Considering this, perhaps the desire for shared feeling that has flowed constantly at the foundations of Choi's works since his experiences at Nanji-do Island and his Sunday Seoul exhibition constitutes the driving force behind his artistic work.

At the heart of this shared feeling, above all, lies the certain level of collective imagination upon which a given community can agree to accept. It is here, therefore, that the unique locality of such a community becomes apparent. The artist's praise for the mundane, demonstration of harmony between the artificial and the natural and questioning of the boundary between the everyday and artificial are strategies for inducing consensus regarding these new powers of imagination. In this context, perhaps his tacky plastic objects print images of the present, call up memories that conform to these prints and elicit consensus on the imaginative power that this enables. Choi's intention is to discover highly unique communities of memory by borrowing the patterns of the everyday; clearly, then, his desire is like that of an ambitious “almost always artist” attempting to save the ruined present.

Choi, it seems, wants to leave the present as the present and to make all of its nuances resound as loudly as possible. Is this not a Kabbala of sorts? When it comes to the likelihood of this sensation acquiring depth and amplitude, the crucial thing is an imaginative consensus which believes this to be possible. The procedures of consensus that Choi has mastered – all the repetition, the unforgettable crude colors, the close-ups of tacky objects – leave an indelible impression. Hanging in the distance at the far end of this impression, perhaps, is the eternity for which he longs. Choi's yearning for eternity is not a conceptual one. He always presents it to us in concrete, material form, using repetition, endless change and flashy surface patterns. Accordingly, his works are sensual and firmly rooted in the realm of aesthesis that occurs in the here and the now. This specificity resonates with the shadows of eternity and death. The point upon which his gaze falls captures the present (feeling) but the desire that this feeling continue forever (imagination of the impossible) – the desire, in other words, for eternity – is at work in all his installations and interventions.

Choi Jeong-hwa_Kabbala_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_Kabbala_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Perhaps this is the plastic paradise of which Choi speaks: a space of political affairs in which plastic sculpture can begin; a space of potentially unique freedom. Perhaps it is this aspect of Choi's art that brings a slight religious aura to his excessively trivial, everyday works; something beyond the hackneyed notion that the sacred and the profane are one and the same. I think this is what makes Choi's works something other than kitsch, something other than conventional pop art. I believe this fundamental aspect of Choi has been in operation continuously, at the base of his works, since his experience at Nanjido and his discovery

Perhaps Choi's future museum exhibitions will be infused with deeply melancholy nuances of suggestion, as can be read from the systematic index of his own works that he has laid out on the apple crate altars at the beginning of the Daegu Art Museum exhibition. As Choi has asserted, museums must be places of vividness and life, not of death. The greater the energy of life, the darker the shadow of death. Since all shadows of death are related to that of our own, they are unique, independent and sometimes splendid. The identity of Choi in Korean contemporary art touches upon this awareness. It lies with his ability to socialize his own confessions and his own critical mind, to formulate them as social indicators – in other words, his successful posing of questions in forms comprehensible to anonymous members of the public.

Related Links

Choi Jeong-hwa's website

Choi Jeong-hwa's Kabbala exhibition at Daegu Art Museum

Choi Jeong-hwa Kabbala exhibition

Kabbalah in the Style of Choi Jeong-hwa _ Dong-yeon Koh(Art historian and Critic)

In-sook Nam / Art critic

In-sook Nam graduated from the Mathematics Department of Kyungpook National University before receiving a master's degree and doctorate from the Aesthetics Department of Hongik University Graduate School. She currently lectures to graduate and postgraduate students, while maintaining ties with reality through exhibition planning and criticism. Nam is the author of Lacan's Theory of Subjectivity and Contemporary Art (doctoral thesis, 2011) and a co-author of Walter Benjamin: Modernity and the City (Raum, 2010). She planned Fantasy ? Will be there (2013), the inaugural exhibition of Daegu Art Factory. Nam has also authored many essays on subjects including surrealism and psychoanalysis; the general public, discourse and issues of art; and artwork analysis from a psychoanalytical perspective. In terms of art, Nam is interested in analysis of artworks and discourse; in terms of aesthetics, she is interested in the mutual relationships between subjectivity, ethical issues and art. Her principal research methodology is Lacanian psychoanalysis.