It was the perfect decision to choose art of spirituality as the agenda for a venue for discussion on art held in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Choosing such a heretical theme, when old powers in the art world still stand firm and an international art event often come up with sociopolitical themes, is either peripheral or sporadic. The Gwangju Biennale clearly sets forth a more differentiated message of Gwangju by exclusively addressing the spirituality of non-Western art through this project. The exhibition provides an opportunity for new reflection on “spirituality in art,” while creating a premodern, modern, and postmodern context in Asia. It does this work by generating messages of sorrow, healing, consolation, and coexistence and iconography of religious rituals as well as science and art that propose a new spirituality on nature, society, and human by reflecting on the universe, life, and brain.

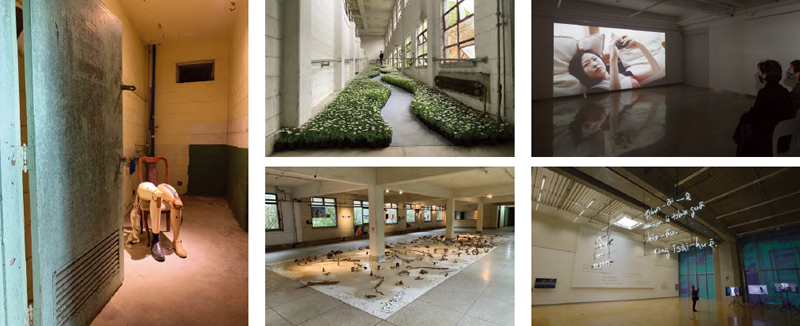

Gwangju Biennale Exhibition view(gallery 1). Image provided by Monthly Art.

Mind, Soul, and Spirit

SciArt creates cosmic mystery with drawings of light that glide through the darkness and create the entrancing instant moments of spirituality the audience feels intuitively, albeit not explicitly. The best artwork in the exhibition is Gravity’s Dance by Liliane Lijn. Lijn, an artist influenced by literature, alchemy, surrealism, Buddhist poetry, and physics, combines poetic language, movement and light, concrete poetry, and kinetic sculpture. Driven by her interest in the female archetype, Lijn’s work further expanded based on scientific theories and convergence technologies. The artist’s achievement in pursuing art of convergence shined more than ever in her piece for the exhibition through light drawing that visualizes the power of the universe with abstract language. It visualizes the non-visual energy based on physical presence, delivering the beauty of projecting a scientific narration of black hole and gravity into the realm of the beyond, or the realm of spirituality.

The exhibition, which addresses spirituality and art, begins from distinguishing the mind (“마음”) and the spirit (“정신”). In Korean, the two words have different nuances. “마음” is pure Korean word, while “정신” is a Chinese loan word. But “마음” and “정신” are used interchangeably in Korea. This is because the terms are often used in sets, such as “the body and the mind,” “the flesh and the spirit.” Therefore, Koreans use them interchangeably However, as foreign art directors communicate in English as a global language, one needs to take a look at the English terms. In English, “mind” refers to “the element of a person to think rationally,” while “sprit” refers to “the essence of the human soul.” Compared to the mind, spirit is more intuitive and emotional in English context. Therefore, one needs to carefully examine the nuanced translation of the exhibition title Minds Rising and Spirits Tuning from English to Korean.

From a neuroscientific perspective, the boundary that separates reason and emotion bears no significant meaning. It is why today’s brain research focuses on cognitive science. However, to take a look at the exhibition’s intention to separate mind and spirit, the mind can be adjusted according to our sense of purpose. All human cognitive acts fall within the scope of the workings of the human mind. The brain has a series of mechanisms from emotional memory to emotions, feelings, and thoughts. Therefore, theoretically, humans can control the mind. The spirit is connected to the matters of the soul, founded on the belief that it can or does work separate from the human body. For that realm of possibility, humans have created irrational, emotional, and sometimes even incomprehensible concepts like transcendence, intuition, and the unconscious.

Premodernity in the non-Western world could be an opportunity to move beyond the framework of reason and rationality weaved by the Western-centric modernity and restore the basic mechanisms of human senses. Like how we developed artificial intelligence (AI) to expand our intelligence, which refers to the intellectual capacity of human beings, we can restore the intrinsic intuitive potential embedded deep within our basic instincts. The evolution of civilization achieved a legend of great progression built on the rationality of science and technology, but it has been long since the reflective introspection on such progress. Many claim that we need to revisit the issue of spirituality beyond the realm of science to achieve transformation in civilization. In other words, human beings discover a new alternative in spirituality beyond intelligence, like how AI unfolds reason and new emotions for us.

Gwangju Biennale Exhibition view(gallery 2). Image provided by Monthly Art..

Rising Minds and Tuning Spirits

The keywords in Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning reflect the basic structure of the dichotomy of the West and the non-West. The exhibition unfolds the narration of life and death that exist in every corner of the lives of the non-Western world. But due to its distinct difference, it ironically stresses the cultural globalization through Westernization more evident. The sections across the five galleries of the Biennale Hall are full of issues that transcend the dichotomous boundary of nature and human, center and peripheral, men and women, and life and death. They are held under the subthemes of 1) Rising Together, 2) Kinship of Mountains, Fields, and Rivers, 3) Bodies in Desire, Beyond the Disciplinary Fold, 4) Matters of Mutation, and 5) Matriarchy in Motion.

The collections of the Museum of Shamanism and Gahoe Museum shone brightly. The cultural anthropological relics, including various auspicious paintings as well as images that hold talismans or symbols of shamanism, exist in harmony with contemporary artworks, delivering art of healing that blurs the boundary of life and death in a creative way. Korakrit Arunanondchai’s Songs for Dying presents art to recover from trauma through a narration of life and death by sharing personal and collective experiences. Sang-don Kim talks about the reality of the contemporary by appropriating the shapes and colors of Korean traditional bier and elements of sculptures and installations.

Gwangju Biennale Exhibition view(gallery 3). Image provided by Monthly Art.

One of the most distinguished part of the exhibition is the museography that is in line with the theme of spirituality. It weaves the entire space into one visual narration, enabling each of the artworks to have a distinct presence. Instead of dividing up space, breaking up, and reconnecting the flow of path, it creates a sense of space through distancing and lighting and forms a closed yet open space using translucent fabric. Moreover, one of the greatest merits is that visitors do not have to endure the roars of video clips. Unlike any other biennale exhibition, where most of the time visitors are dazed from visual and auditory stimulation, this piece creates a clearly differentiated space composition.

However, this does not mean that the exhibition is just silent or plain. Images of religious rituals such as auspicious paintings, Buddhist paintings, or images of places of gut (exorcism) and talismans provides an intense drama transcending across life and death. Such design allows the audience to feel an atmosphere of watching a well-written play, while creating a flow of scattered and tightened senses through unexpected parameters. Between gazing and glancing, visitors freely go in and out of the exhibition space. This enables temporary release of senses for the audience, while providing a time and place for emotional reaction instead of unfamiliarity.

Gwangju Biennale Exhibition view(gallery 4). Image provided by Monthly Art.

The Spirit Gwangju beyond its Territory

I would like to introduce a work that represents an aesthetic arrangement that makes Gwangju not a story of the past, but a story of the present. Cecilia Bengolea, a South American artist and democracy movement activist collaborates with Gwangju-based painter Sang-ho Lee who led an art movement in Gwangju in South Korea and suffered painful torture. In addition, Filipino artist Cian Dayrit’s work illustrates the current military dictatorship in the Philippines. These works represent Gwangju Biennale as a venue for intensive discussion on art, where the history of East Asia weaved with the days of the past and the present and the narration of democracy and human rights commune and stand in solidarity. But some people insisted the removal of Sang-ho Lee’s artwork for political reasons. In this context, artists have come together to sign in solidarity for the protection of freedom of expression. The situation shows that the spirit of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising is not just a movement that was over in the 1980s, but is still present in our lives here in South Korea, in Asia, and in the world in 2021.

Gwangju Biennale Exhibition view(gallery 5). Image provided by Monthly Art.

According to curator Joo-won Park, who participated in the research of Asia and artist selection as co-curator, the art directors and curatorial team did not want to simply make Gwangju Uprising into images. Instead, they focused on remembering the history and memories of Gwangju beyond its physical space, while not bringing the historic event to the surface explicitly. They wanted to show that “Gwangju was not an isolated event but rather a part of human history that keeps repeating itself.” Sometimes South Koreans might think that South Korea overcomes the unfortunate history by looking at other Third World countries like Myanmar. But in fact, the crisis in Myanmar is also relevant in South Korea today. The exhibition planners aimed to continue to carry on the legacy of the spirituality of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising under the name of “Gwangju Spirit.”

The continuum of Gwangju spirit demonstrates the historic lesson not limited to Gwangju area. It is an insight that people of Gwangju recovered from the painful memory (like Myanmar) or catharsis emerged by relating to the pain and sufferings of others. Furthermore, standing in solidarity with the Other thereby, opens a path of healing. In this context, the exhibition addresses Gwangju in depth without directly and explicitly addressing Gwangju. And it is meaning that such a discussion on art is happening in Gwangju, a city consumed of personal and collective trauma. It is about reflecting on the collective trauma remaining amongst citizens of Gwangju, who experienced the tragedy of the 1980s, much like the collective trauma of South Korea that witnessed the Sinking of Sewol on April 16.

Gwangju Biennale, Exhibition view(Horanggasy Artpolygon,Gwangju Theater). Image provided by Monthly Art.

The Materialistic Understanding of Spirit and Art

Wassily Kandinsky, a Modernist of the 20th century discussed reductionism in terms of “harmonic theory in painting” in Concerning the Spiritual in Art. The current Gwangju Biennale focusing on the spiritual in art pursues the reverse of reductionism and aims for the spread of artistic value. It is along the lines of the contemporary that transforms modern art theory into postmodern art theory. The exhibition examines spirituality in art in the postmodern context, not as a regression to the past. Human spirits consist of perceptible senses and imperceptible senses. Thus, Spirits Tuning sheds light on human senses that cannot be discovered with only logical cognitive ability.

The concepts of “soul” and “divinity” are abstract. To a materialist like me, the concept of “soul” is an element that disrupts a deep understanding of artistic communication. Therefore, it is unacceptable for me to talk about the soul in artistic creation, art criticism, or interpretation, from a religious standpoint. Nevertheless, the exhibition is still fascinating to deal with spirituality because of its premodern and non-Western perspective as well as a postmodern view. In this sense, I believe the terms such as “spirit” or “spirituality” are more accurate than “soul” or “divinity.” One can discover a 21st century version of “the spiritual in art” based on the materialistic understanding of “spirit, spirituality, or the spiritual’” in relation to artistic thinking, practice, and communication.

A scientific understanding of spirit and spirituality is the foundation of spirituality in art. Thus, the exhibition’s approach to spirituality through scientific art is very suggestive. It is meaning that addressing spirituality in terms of a cognitive science. It unveils the potential of spirituality in the contemporary sense. In addition, the exhibition raises the question of how AI influences human cognition and its relationship with the realm of human spirituality. In a neuroscientific perspective, the human body and the human mind are inseparable. This proposition paradoxically is related to premodern archetypal thinking, not modern rationality.

Gwangju Biennale, Exhibition view(Former Armed Force's Gwangju Hospital, Asia Culture Center(ACC)). Image provided by Monthly Art.

Even if the exhibition brilliantly explores and reflects on the human mind and spirit through the legacy of premodern spiritual culture and cutting-edge brain science and AI, the matter of soul remains unsolved. “Soul” is a fundamental existential issue that divides into materialism and idealism. We are back at square one at the face of the concept of soul even if we successfully conduct artistic communication based on an understanding of the human mental processes such as the mind and the spirit, logical rationality and emotional response, analysis and interpretation, and insight and intuition. We bear the burden of addressing the concept of soul, whose existence cannot be proven, as finite creatures in one corner of this universe.

This might be the remaining question of the exhibition Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning. It is paradoxical to deal with human history and culture in terms of science and art but at the same time of religious rituals and everyday lives. In shamanism, Buddhism, and the world view of East Asia, spirit cannot be separated from the body. In some sense, the shamanistic world view based on the belief that life and death is identical is in line with the scientific understanding of the universe and life. The Gwangju Biennale 2021 seeks an alternative way to overcome the dichotomous thinking of the West that separates life and death, by “raising the mind and tuning the spirit.” for our contemporary society and art.

Kim Jun-Ki

Chief Curator, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea