Installation artist, interior designer, art director, collector - Choi Jeong-hwa, an artist with multiple labels active in all fields of contemporary art, is holding a solo exhibition at Daegu Art Museum. Choi's works are renowned for their colorful brilliance and diversity; the Daegu exhibition is notable for being the first to present a comprehensive collection of his works in one single museum space. A variety of objets, everyday items, mass-produced industrial goods and collected garbage fills the exhibition space, exuding the aura of an artist whose work commonly features in biennales around the world and who is more active overseas than in his native Korea. Art talks offering various perspectives onto the exhibition and works within it through expert cross-critiques offer glimpses into Choi's solo Kabbala exhibition and the world of his work through the eyes of art critics or art historians.

Kabbalah in the Style of Choi Jeong-hwa

Choi Jeong-hwa's current Daegu Art Museum exhibition, which opened on March 12, is the first chance in quite a while to see his works gathered in one place in Korea. Until now, most of Choi's work in the country has been displayed outside museums, in the form of public art; his 2006 exhibition at Ilmin Museum of Art, strictly speaking, was not a solo exhibition by Choi but an exhibition of other artists and collections, curated by Choi. To put bluntly, however, this exhibition leaves a lot to be desired. It could be said that Choi's works are at their most radiant when communicating with the environment and with viewers outside museums; or, it could be said that his innovative display style may not be suitable and less prepared for the actual conditions of a museum.

Choi Jeong-hwa_Kabbala_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa_Kabbala_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

There appears to be no problem with Kabbalah as a concept, used in conjunction with the exhibition's subtitle, “alchemy.” The concept of transformation emphasized in alchemy is linked to Buddhism, which played an important role in Choi's works and artist’s philosophy. In a recent interview, Choi stated that he had encountered the concept of Kabbalah in Japan and become interested in the notion of three stages of transformation: “the myth of reduction, the broken dish, and restoration.” He also quoted the conversation between Walter Benjamin and Gershom Gerhard Scholem, the philosopher who founded modern, academic study of Jewish mysticism: “ ‘Tradition is not something that has always existed, but something always new, something that is accepted, interpreted and readjusted by current generations. Kabbalah is interested in tradition not in order to preserve it but in order to transform it. Kabbalah respects the past in order to sever itself from it'. When I first discovered the word 'Kabbalah', I didn't know that. I found it out by chance, while reading another book. I was surprised. Isn't that splendid?” 1) In fact, given that the objects Choi uses are outdated consumer items resulting from the differentiation processes of early consumer culture, it appears that the Kabbalah-esque way of thinking – not a history of progress and change but a process of looking back to the past and creating new things from it – bears similarities to Choi's attitude as an artist. The transformation of which Kabbalah speaks, moreover, resembles the Buddhist doctrine of samsara, which holds that forms from previous lives are newly judged and reborn in different forms in subsequent generations.

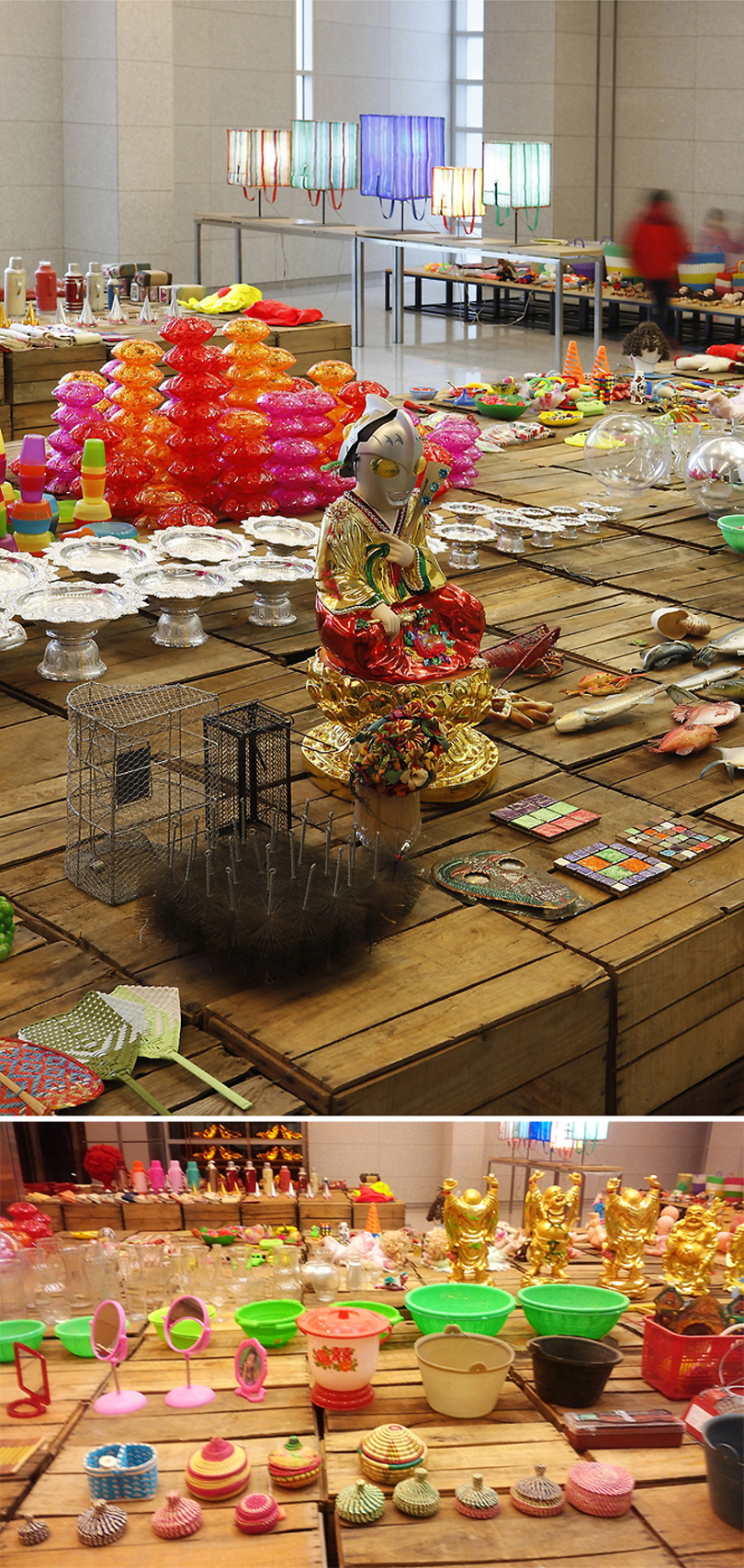

The problem of transformation is a central concept in both art and Kabbalah or Buddhism. In contemporary art, of course, the conceptual substitution of and breaking away from meaning, rather than physical transformation, is used as the principal transformative strategy. Examples of temporal, social and aesthetic changes in position in terms of treating objects from the past or without economic value as valuable items – the placing of ordinary everyday objects inside an art museum being a classic example – count as effective strategies of transformation. The objects placed on display stands, as well as being worn out and dilapidated, serve as reminders of Choi's travels. If his previous exhibitions have been derived from the tacky consumer goods and plastic objects that appeared from the 1960s to the 1980s as part of Korea's process of modernization, and from fake imported cultures, the main theme in this exhibition is tacky “exotic” objects collected by the artist while traveling. To put it another way: the objects here are from all manner of places as well as all manner of times.

1) Choi Jeong-hwa, interview with Yun Ji-won. “Choi Jeong-hwa: nobody.” From Choi Jeong-hwa's own archive

Choi Jeong-hwa _Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa _Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

The method used to categorize and display trivial entities and objects, linked to the aim of discovering new value in them, leaves many viewers with the impression that these items have been bestowed with an entirely different kind of value. Old household items and toys, on the verge of being discarded, are displayed as if in a museum of anthropology. The method used to line up various children's toys according to similarity of form is reminiscent of the categorization systems used by natural scientists to classify animals on the basis of similar form and function. Indian stainless steel dishes sit next to Indian decanters used for tea or milk; Japanese patterned cloths have been placed by similar patterns or by origami paper hats. The appearance together of such patterns and craft techniques among Asian countries emphasizes a feeling of “Asian” solidarity.

The classification and arrangement of objects in this way produces some totally unexpected meanings. The wooden ornaments bought by the artist while traveling in Southeast Asia, for example, reflect his own personal tastes and the routes he traveled rather than their similar functionalities. Given Choi's preference for old objects, many of the household items and toys he has displayed here are no longer produced. The very act of collecting and classifying enormous thermos flasks, or toys whose use we can barely guess at, holds historic significance. In his 1966 work, The Order of Things, French philosopher Michel Foucault famously describes the process of how classification, by organizing and extracting similarity from various entities and objects, forms the basic way of thinking and knowledge of a given society or era. In which case it is possible, at the same time, for us to change existing common ideas and systems of language and culture by using categories in new ways, or by creating new methods of classification altogether. The very act, by artists, of collecting and displaying objects irrespective of their conventional uses is an example of revolting against such typical systems of classification and knowledge production. 2)

2) Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Random House, 1970), p. Xix. Foucault explains that it is culture that has played a role of inserting new “grids” into existing linguistic and epistemological systems.

Choi Jeong-hwa _Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_2013_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa _Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_2013_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa _Furniture Family_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa _Furniture Family_Daegu Art Museum_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Despite these achievements, Choi's objects appear fundamentally too familiar and not shocking enough to produce any critical insight. The artist explains in his own particular way that the exhibition, brought into a museum, inevitably acquires a dignified aspect. “Goods, products, artworks. They all have to have 'class.' Art is no different from design.” 3) The process of putting utterly unartistic objects in an art museum in order to mock the “class” of art, however, requires the effect of some kind of distinctive twist. The problem is that the objects collected by Choi in this exhibition are no longer that unfamiliar and no longer appear so crude. That is not, of course, to say that his exotic objects are fundamentally uninteresting. But in the consumer culture of today, when tastes are becoming more rapidly differentiated than anything else, “retro” style is no longer the exclusive preserve of fine artists or other visual artists. It is now easy to get hold of vintage cultural objects or exotic items from various Asian countries on the Internet, or in fashionable alternative districts of Seoul such as the region around Hongik University.

3) Yun Ji-won interview (see above)

Choi Jeong-hwa _Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_2013_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

Choi Jeong-hwa _Sallim_Daegu Art Museum_2013_(image courtesy of Daegu Art Museum)

In the same way, Choi's method of mixing various times in his work is relatively simple and not particularly shocking. The concept of time according to Kabbalah is not subordinate to the concept of the physically progressing past, present and future to start with; distancing itself from the Western-style, developmental view of time that simply holds that the culture of the past develops into the present, it connects various fleeting moments from past, present and future. Choi's objects, too, could have become objects of new memories, combining past recollections with ideal future states and temporal experiences, rather than simply objects of the past developed into the present. His works fail, however, to give clear answers to the questions of how memories of old objects communicate with the present and how they change present circumstances. The artist may, of course, counter that his wish is for his works to remain in a state of playfulness without providing any particular answers. His pig-shaped balloon, light in appearance but seemingly far too heavy to float in the air, can be regarded as an embodiment of this. This Jeff Koons-style balloon, unable to fly, is a not a traditional symbol of luck but a symbol of failed luck. Its brilliant color, however, prompts the viewer to abandon all complicated thoughts and concentrated instead on fleeting pleasures. Even putting aside the basic questions of whether these “time-worn” products really criticize the “class” of art and whether this symbol of luck has really been transformed into a symbol of humor, it remains a pity that Choi's method of dragging the objects or symbols of the past into the present is not more complicated. The temporal concept of the Kabbalah is not simply one of mixed time, but one that simultaneously supposes a constant yearning for an unattainable future.

I therefore assumed, at first, that this exhibition would come up with new ways of introducing the audience-participatory works that Choi has been developing over the past 10 years. The Happy Happy series, made from recycled plastic items, could engage with the environmental issues faced by our society through its use of discarded objects, despite its simplicity. Given this, I believe it has the potential to offer answers when it comes to the meeting of past and present. (There was, of course, an installation similar in appearance to the Happy Happy series but its presence was too weak, in terms of both location and size, for it to even be regarded as part of the exhibition.) I was curious, moreover, to know how Choi's utopian works are developing these days, given his participation in Ssamzie's organic farming project, called Yuginong Gagae. Consequently, this exhibition got me thinking about Choi's artistic world and about art museum exhibitions. It occurred to me that this show could actually be taken as a cue to look forward to bolder art museum exhibitions from Choi in the future.

Related Links

Choi Jeong-hwa's website

Choi Jeong-hwa's Kabbala exhibition at Daegu Art Museum

Choi Jeong-hwa Kabbala exhibition

A natural history of the present, by Choi Jeong-hwa _ In-sook Nam(Art critic)

Dong-yeon Koh / Art historian and Critic

Dong-yeon Koh is currently writing a book about the process of differentiation between contemporary art and consumer culture in East Asia. She has published critical writing on understanding history through the art of Takashi Murakami and on marketing strategies in art (Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 2010), and on the emergence of Choi Jeong-hwa's works using vintage art as part of the differentiation process of consumer culture in Korea in the 1990s (Korean Society of Basic Design and Art, 2012). She currently lectures at Korea National University of Arts.