This article aims to re-examining the 40th anniversary of Young Korean Artists. 《Young Korean Artists》, which started with Youth Artists Exhibition in 1981, is a program to discover emerging artists by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA). About 400 young artists were introduced over 20 exhibitions. This year fifteen artists were selected: Kang Ho-yeon, Kim San, Kim Jung-heon, Nam Jin-woo, Noh Ki-hoon, Park A-ram, Bae He-yum, Shin Jeong-gyun, Yohan Han, Woo Jung-soo, Yoon Ji-young, Lee Yoon-hee, Choi Yoon, Hyun Woo-min, and Hyun Jung-yoon. It encompasses a variety of diverse genres, such as painting, sculpture, video, installation, photography, pottery, and performance, and includes artists working locally and abroad. This article pays attention to the symbolic meaning of Young Korean Artists in the Korean art world. I argue that the exhibition should adopt active planning to capture the space of the new generation and encourages people to focus on the dynamics of “young” art in Korea.

Posters of 《Young Korean Artists》 Starting with the 1981 Youth Artists Exhibition, Young Korean Artist is the oldest artist discovery program at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. About 400 new artists have been introduced to the public over 20 exhibitions until now. Image provided by Art in Culture.

From an Alternative Space to a New Space

The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea's 《Young Korean Artist》s marks its 40th anniversary. The exhibition was held for the 20th time this year after starting with Youth Artists Exhibition in 1981 and changing its name to Young Korean Artists in 1990. What does “young” mean in art? It would generally refer to the activities of new artists who have newly entered the art scene. Yet it does not just mean the biological age of an artist. The essence of “young” is the “artistic age” that shows new characteristics that are differentiated from the styles and practices of the existing art system and replaces the formations of the past. Then, why does the art production scene give so much value to “young art”? This may be because the practice of new art without any definite guarantees in a small-scale limited art world becomes a driving force to lead the entire art field against the economic stability of established art.1)

Since the mid-1980s, the small group movement, which had emerged as a so-called “new generation of art,” has caused a major change in the hierarchical order of the Korean art world. Following that, the public forum for discourse of Postmodernism opened, and this tendency continues to expand in the 1990s. As a result, the practice of individual artists was emphasized rather than the existing group movement based on similar styles, and the Korean art community sought for the influx of “young art.”2) In particular, “alternative spaces” and national and public “creative studios,” which emerged as part of the state-led cultural and artistic policy after the IMF financial crisis, supported new artists’ creativity and exhibition activities for biennale exhibitions since the late 1990s. These spaces also contributed to expanding the art auction and art fair markets, company art award systems, and art gallery’s staff artist system. As a result, in the mid-2000s, there was an illusion that “young art” centered on non-profit exhibition spaces that seemed to lead Korean contemporary art.

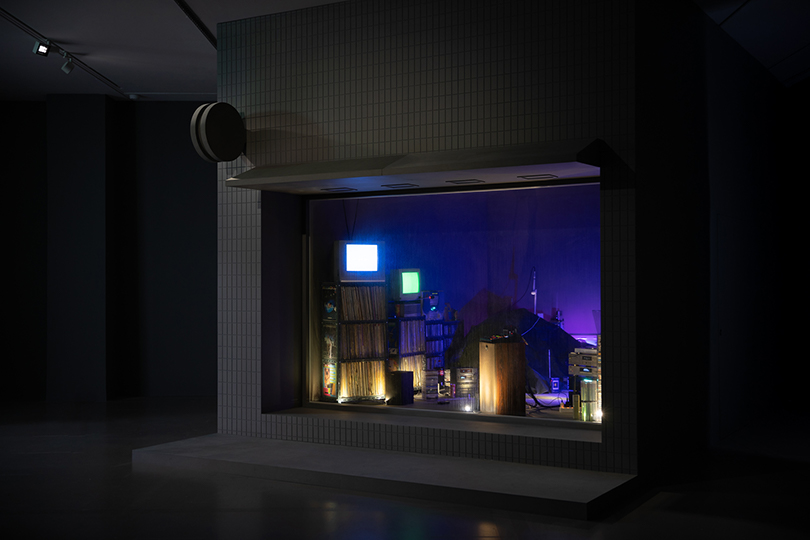

Kang Ho-yeon, 〈Re-Record Violet〉, mixed material, 375×615×360 cm, 2021. The artist used city pop music and images of the night view of Seoul to express the social boom audibly and visually in Korean society before the pandemic. Image provided by Art in Culture.

However, the splendid era of young art, represented by alternative spaces, faded in less than a decade. The art market downsized due to the economic deterioration that began with the 2008 Asian financial crisis, and corporate sponsorship and state support for exhibitions and the award system decreased significantly, resulting in extreme polarization throughout the art market in Korea. As representative alternative spaces were also closed or replaced, the entry and activities of new artists into the art world were also greatly reduced. This indicates that unlike the alternative spaces in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, which were spontaneously created by the artists’ own needs, the alternative spaces in Korea were caused by the need to discover young artists driven by the state and companies due to the sudden expansion of the art market. Some artists, who started in alternative spaces and faithfully climbed the institutional ladder, were able to obtain symbolic capital with economic success, or gain full-time positions, such as college professors, in education centers. But it was difficult for most young artists to enter the art market and take all the risk by themselves under these circumstances.

Under these unfavorable conditions, the so-called “new space” was created by emerging artists in the 2010s for their own needs. Unlike alternative spaces where the state, businesses, established artists, and planners were the main agents to discover young artists, these new spaces were founded by young artists in the early and mid-1980s who graduated from college and started their career. By the time they entered society after experiencing the IMF crisis as a teenager, these artists began to create small spaces that combined exhibition and production together to save rent and operating costs as much as possible.3)

Some argue that the era of “new space” is over and call it the era of “post-new space.”4) This evaluation is correct on the one hand and wrong on the other. Many of the new spaces established in the 2010s disappeared, but other new spaces also opened. In addition, some of the people who previously operated new spaces planned various platforms and projects, or prepared other unique spaces. Above all, opening a space has become much easier than before. This tendency shows flexible space utilization, such as sharing one space with multiple people or holding project events in existing spaces. Therefore, new space is not just a “newly constructed space” at a specific time but is more of a term referring to a specific way and attitude of “creating a new space” or “dealing with a new space.”

〈Young Korean Artists 2021〉, Yoon Ji-young’s section. Yoon Ji-young shows the appearance of a modern subject who is becoming self-conscious in an isolated pandemic situation in various sculpture forms. Image provided by Art in Culture.

Concept of Self-Organization and Sharing

In two aspects, new space is not simply a phenomenon specific to the Korean art world. It is related to the issues discussed in the field of global culture and art around the world based on changes in social structure. One aspect is “self-organization” and the other aspect is the concept of “sharing.” First of all, the concept of self-organization, which began to be actively used in the field of culture and arts in the mid-2000s, refers to various independent art practices pursued by artists as a strategy to reduce uncertainty in the expansion of free market ideology.

Several issues can be related to the practice of new space. For example, artists seeking self-organization emphasize their personal motives and independent practices as subjects of “non-material labor,” not as members of the economic development desired by the state in a neoliberal system. In addition, regardless of the number of participants, such as individuals, collectives, and groups, these artists highlight the relationship between each subject. In particular, they seek to eliminate the hierarchy among members, choose an open participation model in decision-making and value cooperation and solidarity. Above all, the key to self-organization is not unconditionally rejecting the existing system but reducing dependence on it. For instance, considering the precedent in which spaces that were entirely dependent on public funds were forced to close when public funds were reduced, these young artists discuss the practice of self-organization in terms of diversification of space management.

On the other hand, the practice of “new space” is deeply related to the “sharing society,” which began to be emphasized as a concept to overcome the limitations of existing capitalism after the neoliberal system. “Sharing” is actually a very old survival strategy for mankind. Following the model of farmers’ guild management of resources in preparation for the exploitation of lords in feudal society, various types of non-profit sectors were established by workers to use shared resources together as factory owners took the place of lords after the modern industrial revolution.7) Currently, this concept is attracting attention from the perspective of a sharing economy that borrows and shares goods and services based on the Internet. It aims to overcome the limitations of capitalism resulting from making all aspects of human life exchangeable products, i.e., possessions, by sharing various resources within networks according to one’s needs. Rifkin states, “I don't think the capitalist market will disappear completely . . . [Yet] more and more economic life will be based on a cooperative sharing society.”8)

In this context, new spaces have the characteristic of being “shared” in that they prioritize access rights over ownership in horizontal relationships. Borrowing or renting space allows several people to build relationships from that space and practice art that creates value. This is possible because the platform of new space aims not at a hierarchical relationship based on the institutional selection but adapts a method of sharing generated profit in a horizontal relationship with artists who want to enter the art world. In addition, they actively utilize social media to facilitate the practice of sharing. In addition, promoting, exhibitions, introductions of works, and sales are centered online. This characteristic of new space is related to Web 2.0, in which users directly produce and share information on an open platform.

Yohan Han, 〈Resonance Operation: Conversation〉, 5-channel video, 15 minutes, 2021. Various forms of tactile senses are reproduced by multi-media work such as objects and performances using drums. Image provided by Art in Culture.

The Subject of Post-Internet Art

The Internet significantly contributes to the operation of new spaces and attracting audiences and plays a key role in art creation. Artists born since the late 1980s are “digital natives” who have been using computers and smartphones in their daily lives. As a result, the Internet, computer devices, and various programs are commonly used in their works. In this context, they are collectively referred to as the “post-Internet” generation. The term “post-Internet” is a name that emphasizes the difference from “Internet art” that attempted to create and appreciate art in a virtual space on the Internet with the advent of the world wide web (www) in the late 1990s. Beyond using the Internet as a single media, post-Internet artists organize a database of images through web surfing, transform it within several software programs, combine it with traditional media, and showcase it in the actual exhibition hall.

Therefore, post-Internet art appears in various aspects across virtual and real spaces. In addition to “post-Internet,” a name that emphasizes the prevalence of the Internet, post-medium trends, such as “post-photography”, “post-cinema,” “meta painting,” and “meta sculpture,” are becoming a new avant-garde in contemporary art by combining and borrowing digital technology in the form of traditional media.

For the post-Internet generation, computers and the Internet are not only specific media or methodologies, but also constitute a world view to which they belong. Most of them first conceive works on a two-dimensional monitor for a three-dimensional exhibition space. While contemplating how to extract the image from the screen into a material object, they find the gap between dimensions as an important component to decide the actual art format. The subject matter and content of the works also includes online subcultures such as games, animations, popular music, fashion, and social media, which have dominated their daily lives for a long time. It also appears as a unique formal feature in the process of projecting or printing a low-resolution image modified on a computer and a screen, unlike conventional high-definition image work. In other words, what Hito Steyer refers to as the “poor-quality image” expelled from the screen, ironically is revived as post-Internet art.

Above all, the Internet they use in their daily lives and work is a representative horizontal network system that anyone can access to freely share knowledge and information as a social infrastructure. In addition, with the advent of smart devices, Internet-based network activities can be carried out anytime, anywhere, in that the overlapping range between virtual and real spaces has expanded even further. The Internet has contributed to creating new spaces and attracting new audiences, but it also plays a key role in art creation methods and aspects. In this regard, it is necessary to pay attention to post-Internet art overlapping with the subjects of the new space movement.

Choi Yoon, 〈A Road Heart Goes〉, single channel video, sound, 30 minutes and 30 seconds, 2021. Choi Yoon unveiled two works, Walking on the Dead End and A Road Heart Goes. His video works ask what happened in an empty exhibition hall as well as the meaning of “road.” Image provided by Art in Culture.

What’s the Role of a Museum for Young Art?

Since the 1980s, Minjung Art focusing on social criticism has been in the mainstream of the Korean art scene.9) Recently, post-Internet art attracted attention as a strong candidate to replace the influence of Minjung Art. The practice of new space was important in the transition of avant-garde from social art to post-Internet art. Young artists were at the center of the main issues in the field of culture and arts along with the discourse of the young artist generation in the late 2000s. 10) Unlike the existing passive social art that dealt with related issues as work material or content, these young artists accepted the social issues they faced in real life and moved on to action. It was not an art movement for the greater good aiming to change the world, but the practice to create their own place in the barren art world and endure the challenge.

《Young Korean Artists 2021》, Bae He-yum’s section. Bae He-yum has approached the essence of painting by using pure experience and thinking as the basic unit of color abstraction. Image provided by Art in Culture.

As the individual movements of new space became visible, the existing art system also paid attention to them. The initial interest focused on the generational characteristics of young artists and new small spaces created by them in underdeveloped areas. However, it was difficult for the established system to fully accept the nature of those autonomous creations based on conditions and needs of individual members and voluntary relationships among members. At the end of 2014, as the project of establishing a Young Artist Museum at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea led by critic Lim Geun-joon failed, the Seoul Babel Exhibition (Seoul Museum of Art 2016), which reproduced only the physical appearance of a new space with plywood and scaffolding, was evaluated to damage the vitality of the new space movement. 11)

The subjects of the new space movement entered the mainstream system when major art institutions paid attention to their post-Internet trend works. Starting with the New-Skin exhibition (Ilmin Museum of Art, 2015), special exhibitions have been held at major art galleries over the past few years,12) new space artists participated in mainstream exhibitions and received major art awards. 13) Art magazines also continuously demonstrated their interest in the new space movement from this period.14) In addition, art galleries settled young post-Internet art in the system from various perspectives, including exhibitions of young artists at the SeMA warehouse and a number of related exhibitions at Seoul Museum of Art, which has been holding the Seoul Media City Biennale since the early 2000s. 15) As a 30th anniversary exhibition of the opening of the main building, the Seoul Museum of Art hosted Digital Promenade (2018), including a large number of domestic digital media artists and publishing related books. 16)This illustrates the interest and direction of the Seoul Museum of Art in young art.

Noh Ki-hoon, 〈Yellowhead〉, pigment print, 80×100cm, 2015. Image provided by Art in Culture.

For Sustainable Art

It is undeniable that the MMCA tends not to give young artists a chance to exhibit their works, compared to the Seoul Museum of Art. Recently, there have been some exhibitions of photography and video art,17) , but despite the construction of the Seoul Hall, it is still difficult to find planned exhibitions that show young trends at the MMCA.18) Among them, Young Korean Artists 2019 is the only one. Under the subtitle “Liquid, Glass, and Sea,” the majority of the nine emerging artists presented their works in various media, such as games, vlogs, smartphone applications, and social media.19) As the title suggests, this exhibition had an organic sense of unity enough to remind us of a fluid image wandering through the virtual sea beyond the transparent liquid crystal display screen.

This year’s Young Korean Artists 2021, just two years after 2019, is somewhat different from before. The exhibition seems to be close to a collection of works by various emerging artists without a specific title or topic. In addition, attempts to evenly show various mediums of contemporary art, such as painting, sculpture, pottery, photography, video, installation, and performance, or to secure diversity by arranging overseas and domestic areas feel somewhat contrived. Above all, most of the exhibition works resemble the exhibition of the 40th anniversary archive located in the central hall.

《Young Korean Artists 2021》, The 40th anniversary archive exhibition. It consists of annual books, articles, AR programs where one can enjoy about 20 major entries, and interview videos of curators and artists. Image provided by Art in Culture.

Cliché topics, such as city pop and record shops, nature and totem, heroes and monsters, migrants and personal history, industrialization and the present of a region, and historical landscapes in specific regions, as well as combinations of various genres and modernization of crafts, come without any newness. If “retro” was the theme, the planning intention should have been set more clearly. All 15 selected artists are definitely young artists born in the 1980s and 1990s,20) and many of them participated in recently held major exhibitions, including post-Internet art, but only their biological age is highlighted in this exhibition. In addition, the exhibition design, which separates space for each artist and presents the artist’s name and description on a round sign, only strengthens the impression that they seem to be “named” as the selected artist of the year by the museum.

《Young Korean Artists》 is a truly important exhibition in which the MMCA illuminates young art. Therefore, the symbolic capital given to selected new artists cannot be denied. Nevertheless, it is not an award system nor is prize money. In addition, other than the fact that artists were selected by the recommendation of the MMCA curators and external advisory board, the list of judges or the screening process is not disclosed in detail to the public. Fifteen selected artists are not given any rewards other than special exhibition opportunity hosted by the MMCA. If so, the theme exhibition, which clearly reveals the current trend of young art rather than simply calling the artist’s name, will make their work stand out more. If there is a problem that a themed exhibition that could be biased toward a specific trend, the MMCA may consider a solution that reduces the size but increase the number of exhibitions.

The MMCA is at the center of the Korean art system that gives artists symbolic capital, establishes art history, and provides better exhibitions to the audience by exhibiting high quality artworks. At the same time, they should not neglect their responsibility to spotlight emerging trends in the art scene. It is not only responsible for giving authority to young art, but also for setting various contexts and developing constructive discussions on specific trends. Post-Internet generation artists who are familiar with self-organizing practices and horizontal networks will also want an opportunity for continuous art activities rather than expecting a simple “name drop” by the museum. Perhaps to this end, the museum should implement the artist remuneration payment system, which has been discussed for years, before any other art institutions in Korea, for the sustainability of young art will empower the entire art world to move forward.

1)Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field , trans. Susan Emanuel (Polity Press, 1996), pp.148~154.

2)Several private art galleries led by companies that emerged in the art world began to appear significantly in line with the government’s globalization policy and local autonomy system. They challenged the art world divided into commercial galleries and state-museums, which represented commercialism and symbolic capital. It also increased the attraction of international biennales, such as the Gwangju Biennale.

3)For more information on new space, see my essay “Self-moving Artists: Research on Life Experience and Art Practice of Independent Art New Space Subjects,” Korean Journal Information Journal 76.2 (2016), pp.183-219.

4)Kang Jung-seok, who played a part in the discussion of new space, uses the terms “post-goods” and “post-new space” in a booklet published for the exhibition of Phantom Arm (Seoul Museum of Art, 2018). After the Goods exhibition (Sejong Center for the Performing Arts, 2015) organized by new space subjects, he refers to various platforms similar to the subject and method as “post-goods,” and points out the uncertain future of a post-new space as a “time yet to come” where future generations will be in major roles. Kang Jung-seok, “Log 2: A Game to Maximizing the Minimum between the Two Players.” Magazine Beta 1 (Seoul Museum of Art, 2018), pp.33-43.

5)It is noteworthy that nearly half of non-profit spaces in Seoul have been newly created since 2016, when discussions on new space became relatively prevalent. Between 1999 and 2018, among non-profit spaces opened in Seoul, 53 opened after 2007, 38 opened after 2014, and 26 opened after 2016. “A Study on the Status of Non-profit Exhibition Spaces” (Korea Culture and Arts Commission, 2019), p.84.

6)Starting with the Goods exhibition in 2015, when the new space phenomenon was brought to the surface, exhibitions and events such as The Scrap, Perform, Taste View, and PACK were held one after another for several years. These exhibitions have a kind of platform characteristic that creates the system using empty space without a set regular space and induces more audience interest through social media, so that economic and symbolic capital can be evenly distributed to artists.7)Jeremy Rifkin, trans. Ahn Jin-hwan, Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Rise of the Internet of Things and the Sharing Economy. (Minumsa, 2014), pp.34-35.

8)Jeremy Rifkin, ibid, p. 43.

9)After Minjung art theorists gained a reputation as a new avant-garde movement in the late 1980s, Minjung artists settled in the mainstream art system with the help of planners and theorists in some alternative spaces. For more information, see my work “A Study on Structural Changes in Korean Art Production Site.” Modern Art History Research 43 (2018), pp.89-111.

10)The flow of new spaces began with the Durivan Incident (2009), which showed the role of art in urban redevelopment and gentrification issues, the Labor Day General Strike (2012) in the aftermath of the global occupation movement, and the Art Producer Meeting (2013) to voice contemporary critical issues, such as fair payment for artists.

11)Many of the 15 new spaces chosen by the planner were far from the subjects who led the new space movement in the early days. Simply put, there are only three places, Archive Bom, Now Here, and Hapjeong District, that overlap with Goods.

12)Examples include Push, Pool, and Drag (Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, 2016), Final Fantasy (HITE Collection, 2017), Phantom Arm (Seoul Museum of Art, 2018), When Night Turns to Day (Art Sunjae Center 2019), Your Search, and Research Service in My Hand (Doosan Gallery, 2019).

13)Kang Jung-seok (2015), Kim Hee-cheon (2016), Kwon Ha-yoon (2017), Kim Joo-won (2019), and Kim Kyung-tae (2020) received the Doosan Yongang Art Award, Ryu Sung-sil (2021) received the Hermes Foundation Art Award, and Kim Hee-cheon (2019) and Don Sun-pil (2020) held solo exhibitions at the Art Seonjae Center.

14)Art In Culture has dealt with related discourses in special issues, such as “Post-Internet Art, Is It Over?” (November 2016), “Art of Tomorrow by Internet Generation” (March 2018), “Painting, Is It Changing” (December 2020), and “New Commerce 77” (February 2021).

15)This includes Phantom Arm (2018), Brave New World (2018), News, Dear Ripley (2018), Open Your Storage: History, Circulation, and Discourse (2019), Web-Retro (2019), and SF2021: Fantasy Odyssey (2021). In addition, the Seoul Museum of Art held an independent publishing and design sales event Unlimited Edition (2019), which was held at the Ilmin Museum of Art in 2015 when Goods was held.

16)Embracing the Parallel Worlds: Conditions of Art in Thousands of Small Futures (Seoul Museum of Art, Hyunsil Cultural Research, 2018) includes writings of Korean theorists Lee Hyun-jin, Kim Ji-hoon, and Kim Nam-si, as well as Yoosi Parica. Edward A., Shankon, and David Jocelyn.

17)In the case of photography, there are Public to Private: Photography in Korean Art since 1989 (MMAC Seoul, 2016) that outlines Korean contemporary photography history, and Civilization: How We Live Now (MMCA Gwacheon, 2018) that presents international and domestic representative photography works. In the case of video art, good examples are Korean Video Art 7090: Time, Image, and Device (MMCA Gwacheon, 2019) that outlines Korean video art history from 1970s to 1990s, and The Chronicles of Drifting Images (MMCA Seoul, 2019), which presents digitally archived single-channel video works owned by MMCA.

18)The exhibition Uncomfortable Data (MMCA Seoul, 2019), which introduces domestic and foreign digital media works including Korean artists Kim Sil-bi and Kim Woong-hyun, is exceptional.

19)The artists include Kim Ji-young (1987), Song Min-jeong (1985), Ahn Seong-seok (1985), Yoon Doo-hyun (1986), and Lee Eun-sae (1987), Jang Seo-young (1983), Jung Hee-min (1987), Choi Ha-neul (1991), and Hwang Soo-yeon (1981), mostly born in the mid-1980s.

20)This year’s participating artists include Kang Ho-yeon (1985), Kim Jung-heon (1981), Kim Jin-woo (1985), Noh Ki-hoon (1985), Park A-ram (1986), Bae He-yum (1987), Shin Jung-gyun (1986), Yohan (1983), Woo-soo (1986), Lee Yoon-hee (1986), Choi Yoon (1989), Hyun Woo-min (1980), and Hyun Jeong-yoon (1990). This shows a similar pattern to Young Korean Artists 2019.