The annual Korea Artist Prize, conferred by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, was established to support artists who have made significant contributions to Korean contemporary art. Four artists (or teams of artists) are selected based on expert recommendations and a multistage evaluation process, and a final winner is selected based on an solo exhibition of the artists’ latest works. The exhibition provides a look into the currents in Korean contemporary art and the diverse ways contemporary artists are developing and realizing their ideas. “The Korea Artist Prize” exhibition(Aug 31, 2016~Jan 15, 2017) is currently under way at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, and showcases the works of this year’s finalists: Kim Eull, Mixrice (Cho Ji eun and Yang Chul Mo), Back Seung Woo, and Ham Kyungah. Mixrice was selected as the winning team in October.

The annual ‘Korea Artist Prize’, conferred by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, is the most prestigious award that Korea grants to its artists. In the initial phase of the competition, candidates are recommended for the award and four finalists (individual artists or teams of artists) are chosen after an evaluation process. After the finalists organize their exhibitions, a second evaluation takes place and a winner is announced.

Unlike Western art, Korean art experienced no decisive turning point marking the beginning of the modern age. This development must be viewed as the outcome of a different tradition, a different history; it cannot be judged in a simplistic manner as either good or bad. In Western modern art, however, the transition from weighty classical traditions to a capitalist system and a democratic ideology engendered a change in attitudes toward art, the artist’s identity, and the social value and meaning of art. Even still, both in the East and in the West, art criticism remained rooted in the standards and perspectives of the academy.

The institutional direction of the art world began to shift in the twenty-first century. Considering the increasing prominence of global, postcolonial viewpoints in Korean art exhibitions since the 1990s, it follows that vested interests in the art world and in the nation’s academic institutions would struggle to understand trends in the art scene and the increasing diversity of its voices. In this regard, it is hard to identify those definitive events and characters at the center of Korea’s art historiography and its contemporary art scene. Herein perhaps lies the reason that there is no true Korean equivalent to the British Turner Prize or the French Marcel Duchamp Prize.

Above) Mixrice, ‘The Vine Chronicle’, Two-channel video, HD, Sound by: Choi Tae Hyun, 8min 46sec. Image: MMCA Korea

Above) Mixrice, ‘The Vine Chronicle’, Two-channel video, HD, Sound by: Choi Tae Hyun, 8min 46sec. Image: MMCA Korea

If we examine the recipients of the ‘Korea Artist Prize’ over the past few years, we can see that they all touch on controversial social issues and reflect a critical perspective in their work. Kong Sung-Hun’s winning painting (2013) was a landscape of disdain rather than compassion, in the style of a clichéd picture you’d find on a postcard. Noh Suntag’s documentary photographs (2014) accused the nation of presenting a false image to the world. Oh Inhwan’s work (2015) exposed how Korea was creating a social underclass while distorting the truth about what was happening. The winning team for 2016, Mixrice, in their exploration of how indiscriminate development is destroying the ecosystem, offers a composed statement of how life is being harnessed for the purposes of power.

The very existence of a government blacklist of artists, which recently became known to the public, is evidence of how bureaucrats view the artist’s role in society. But Korean artists cannot turn a blind eye to the issues facing modern Korean society, for in every age art has been a means to resist the powers of oppression and an expression of the will to assert one’s own agency. In this same spirit of resistance, this year’s ‘Korea Artist Prize’ has expressed its determination to show how contemporary Korean art is unfolding and how various forms are emerging. Particularly eye-catching were the various media and methods employed this year.

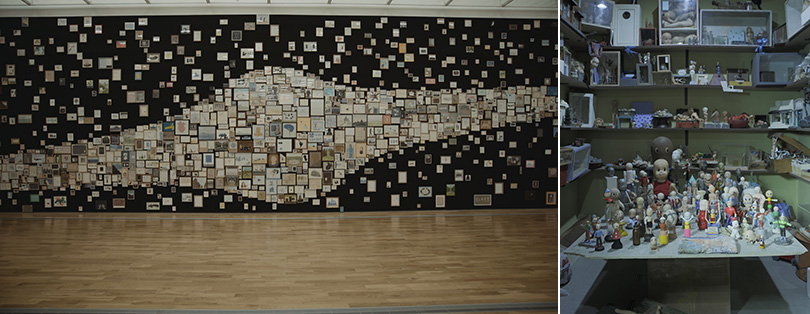

Left) Kim Eull, ‘Galaxy’, 2016, approx. 1450 Drawing installation, 620×2,750cm.

Left) Kim Eull, ‘Galaxy’, 2016, approx. 1450 Drawing installation, 620×2,750cm. Right) Kim Eull, ‘Twilight Zone Studio’(Inside), 2016, Wood, steel, plastic, synthesis fiber, lighting fixtures, paintngs and objects, 560×850×450cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

Kim Eull, a constellation of small pieces

Kim Eull’s work transcended time and place. “Okhari 265 Street” (Project Space Sarubia, 2002) is a piece that centers on the artist’s home, tracing its origins. Going back five generations, his ancestors—their appearance, the landscape they inhabited, their way of life—became the subjects of the drawing. His life was the source of this work. Many artists draw on their lives and experiences. The use of one’s own life as the subject of one’s work was a distinct characteristic of contemporary visual art, and surrealists followed this practice as well. Kim’s work can’t necessarily be viewed as part of this tradition, however. If Ko Un’s collection of poems, Maninbo crosses time and space in all directions, seeing all manner of scenes from life, Kim paints a sincere picture of his own emotional world.

Small fragments of memories are invoked and strangers, from different generations and with different experiences, stand before the familiar things. Through his drawings, he captures the intensity and flow of life, living, self, and self-consciousness. The value of the drawing is in its momentariness. This goes beyond art criticism and is closer to an instinctual reaction. It is akin to us standing in front of the wind, for we cannot deny or evade its effects on us. For Kim, drawing is an attitude and way of life. The composite grandeur of ‘Galaxy’ calls our attention to the greatness hidden in small things—but at the same time, unfortunately, it seems to reduce small things to components of the grand and great.

Above) Back Seung Woo, ‘Betweenless’, 2016, Digital Pigment Print, 30×40×(48)cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

Above) Back Seung Woo, ‘Betweenless’, 2016, Digital Pigment Print, 30×40×(48)cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

Back Seung Woo, an inquiry into photography’s true nature

Modern photography starts with a crucial question about the essence of the photographic medium. Modern photography stems from the hypothesis that it is possible to use this medium to present unique perspectives, perspectives particular to photography, rather than simply to produce images that stand out in their technical aspects. Back Seung Woo questions the political nature of photography as much as its formative potential as a medium. He begins his approach to the politics of photography by dismantling the belief that photography must show truth—that is, the belief that this medium is one that recreates a scene as is. As early as the early twentieth century, the appearance of photomontages established that photography was adaptable. Interestingly, people continued to believe in the ability of photography to reproduce things, and to consume the resulting images. Most people know the difference between what is depicted in photography and reality and yet would rather transcend the real world through this medium. That desire has grown ever stronger in this age of information and intelligence. The development of medicine and other science disciplines holds out the possibility that people can somehow make themselves more complete, or more whole.

Back intends to expose the limitations of the photographic medium, as something that can make some people great and turn others into victims. “Betweenless,” as the title implies, shows its subjects in a context-free state. These are not ID photos; the subjects exist outside any text that would give them context; they merely exist, without identity. So let’s consider the situation in which the subject of the picture (person, thing, nature) exists. We are accustomed to verbally interpreting images. Photographs are subject to this type of interpretation to a greater extent than works in other media. For instance, as painting has endeavored to overcome narrative through the abstract, contemporary photography is making meaningful strides in the visual arts with its attempts to dismantle the customs of photography.

Just as Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow Up (1966) described the relationship between an empty symbol produced by photography and the obsessive fetish attached to it against the backdrop of London’s expansion of materialism in the 1960s, Back is reexamining how today, sixty years later, images are consumed and then immediately neglected. The exhibition is filled with empty symbols; the photographs repeatedly appear and disappear. However, the image of the digital age floats around, continually being reproduced and shared.

Above Left) Ham Kyungah, ‘Unrealized the Real 29,543+1person, 909,084km, 15,000 US dollar’, 2016, Installation(chinese broker, a man who escaped North Korea, subtitle, aluminum, stainless still, monitor, speaker, plywood, sand), Dimension variable. Above Right&Below)Ham Kyungah, ‘Soccer Painting by the Soccer Ball Bouncing Over Crocodile River’, 2016, Video installation, performance, soccer painting, 13years old soccer player, member in Youth FC escaped North Korea, acrylic, soccer balls, soccer shoes, text rubber sheet, paper, wood, light, monitor, sound, 1200×600×300cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

Above Left) Ham Kyungah, ‘Unrealized the Real 29,543+1person, 909,084km, 15,000 US dollar’, 2016, Installation(chinese broker, a man who escaped North Korea, subtitle, aluminum, stainless still, monitor, speaker, plywood, sand), Dimension variable. Above Right&Below)Ham Kyungah, ‘Soccer Painting by the Soccer Ball Bouncing Over Crocodile River’, 2016, Video installation, performance, soccer painting, 13years old soccer player, member in Youth FC escaped North Korea, acrylic, soccer balls, soccer shoes, text rubber sheet, paper, wood, light, monitor, sound, 1200×600×300cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

Ham Kyungah, a commentary on global inequality

Neoliberal economics has divided life from labor, propelling the world into an era of multinational corporations and franchises. Capitalism moves to different production sites in search of cheap labor for profit. Ham Kyungah’s exhibition deals with a promising football player who made an arduous escape from North Korea. The exhibit consists of the colorful traces of a performance, in which the boy spread his wings in search of his dreams, and smooth white sculptures based on the motif of camouflage designs, representations of the difficulty of escape.

Ham uses specific objects to reveal the world’s unequal and corrupt power dynamics. An ‘embroidery project’ undertaken by laborers in North Korea embodies the relationship between artistic activity and labor in the capitalist system and the reality of dated ideology. “Desire and Anesthesia” (2009), a work in which stolen dishes from around the world are displayed as museum artifacts, drew praise from the evaluators for its satirical take on the relationship between history and power and the issue of historical value. On the other hand, this exhibition did not feature the specific context and objects that sets the artist’s work apart from that of his peers. As a result, this exhibition comes off as a somewhat banal work, as if the artist produced it in a rush.

Mixrice, ruminations on community art

Mixrice—a duo comprising Cho Ji Eun and Yang Chul Mo—has put a great deal of work into their works produced in collaboration with migrant workers about immigration and Korea’s post-industrialization future. They communicates through the perspectives and voices of the outsider as represented by migrant workers to satirize aspects of the reality of Korean society that, having become overly familiar, are easily glossed over. Beginning with the experiences of migrant workers, Mixrice seeks continuously to uncover the actual lives that are lived behind Korea’s success as a construction-driven country. This exhibition shows the realities of Korea’s fitful and impulsive life—it documents the process of the stealing and transplanting of land and life.

Mixrice puts into practice a form of communal art, eliminating lofty ideals and critical language and instead forming relationships with real people affected by this process. They don't adhere to any specific framework. They are concerned primarily with reality, and their methods are thus shaped by their deliberations on the actions of art, the evolution of the documentary process, and new forms of participation. In this exhibition which consists of various media and materials and combines installation, drawing, archives, and visuals, ‘The Vine Chronicle’ (2016) stands out as a piece that is powerful not because it stirs up emotions but because of how it bears the weight of meaning. A critique of urbanization, it shows the hastily constructed landscapes and the careless movement of things from one patch of land to another. The transplanted trees seem to be more motifs or decorations than living things. The ‘Badly Flattened Land 2’ of soil in the redeveloped area reminds us of the 1970s situationist art movement. Perhaps this approach will seem hackneyed to some viewers, but it works, mainly because Mixrice are artists who seek to take practical action through their art.

Above) Mixrice, ‘Badly Flattened Land 2’, 2016, Installation(dirt from redeveloped neighborhood), 360×820cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

Above) Mixrice, ‘Badly Flattened Land 2’, 2016, Installation(dirt from redeveloped neighborhood), 360×820cm. Image: MMCA, Korea.

The post-vanishing point era: deliberations in art

This year’s ‘Korea Artist Prize’ will make us reflect on what Korea’s visual arts can do (contribute) in this time when the borders of space-time are crumbling, and ask ourselves again what it means to be an artist today. That requires, of course, the recognition that the contemporary art world no longer belongs to the world of concrete perspectives defined by a discernible vanishing point. Since the era has already broken free from the concept of a vanishing point and the order of space-time has collapsed, society will more persistently demand new outlooks and the taking on of new responsibilities. In particular, questions about the practical and economic benefits of the arts in capitalist societies have ruthlessly undermined the foundations of the art world, not to mention derailed the careers of countless young artists. Under the circumstances, this year’s ‘Korea Artist Prize’ must be further developed into a platform from which to gauge what concerns should now occupy the contemporary Korean visual arts community and how it should express those concerns. It should be a public event that inquires into the characteristics, sentiments, and currents that define/make up the art of Korea.

Jung Hyun / Art Critic, Independent Curator

Jung Hyun is an art critic and independent curator based in Seoul. He is currently professor at Inha University. As an Independent curator he has produced Bonjour, Mr. Courbet(2010), Public art project E+Motion Sabuk and Gohan(2009), Rogues, Image of Others(2008). He also contributes regularly for art magazines in Korea. He received his PhD degree from the University Paris I, Pantheon-Sorbonne.