Features / Review

Yang Fudong x Bae Young-whan Yang Fudong at Daegu Art Museum / Yang Fudong & Bae Young-whan at Platform_L

posted 11 Aug 2016Chinese film and video artist Yang Fudong is holding his largest solo exhibition at the Daegu Art Museum(June 11 ~ Oct 16, 2016). Platform-L Contemporary Art Center also recently organized simultaneous solo exhibitions for Yang and Korean artist Bae Young-hwan(May 12 ~ Aug 7, 2016). Experiencing dissimilar social systems and historical events in neighboring time periods but in differing spaces, the two artists observed the problems of their respective societies, using their work to search for the possibility of healing and a road to salvation.

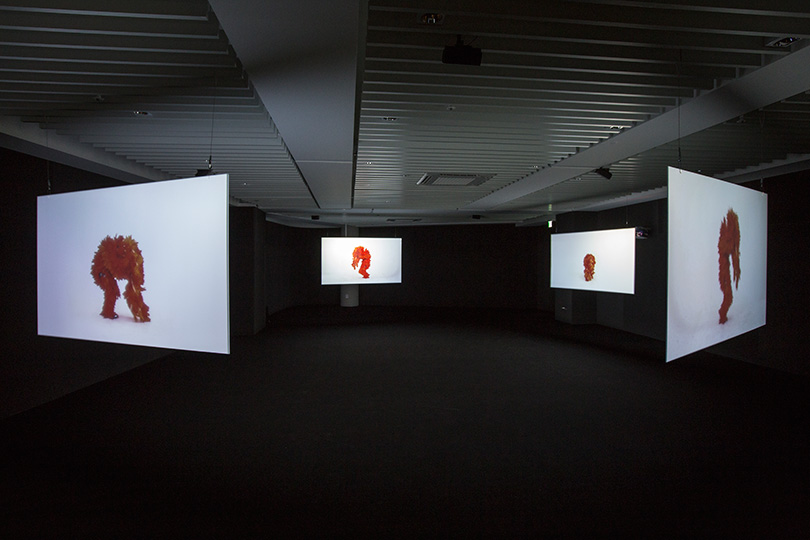

Yang Fudong, ‘Generals smile ’, 2009, multi-channel video installation, installation view at Daegu Art Museum

Yang Fudong, ‘Generals smile ’, 2009, multi-channel video installation, installation view at Daegu Art Museum

Known for visualizing his reflections on the realities and problems faced by contemporary humanity, Yang Fudong, a leading Chinese film and video artist, has recently held two solo exhibitions in Korea, one at the Daegu Museum of Art and one at the Platform-L Contemporary Art Center. The Daegu showcase is his largest solo exhibition to date, introducing Korean visitors to his major works from the past twenty years, from his 1993 experimental work, “Otherwhere,” accomplished as an undergraduate, to his 2014 project “The Light That I Feel.” Viewers are captivated by the over ten of Yang’s works on display, which include his large-scale multi-channel film installations. The well-known ’Seven Intellectuals in Bamboo Forest’ is shown in twenty-two photographs instead of its video form.

Before the Daegu exhibition, the Platform-L Contemporary Art Center in Seoul simultaneously organized shows by Yang Fudong and Bae Young-whan for its ambitious inaugural exhibition. Titled “The Colored Sky,” Yang’s exhibition featured a single work, ‘New Women II,’ his latest HD color film, played on five screens set up in a large underground space. Entitled “Pagus Avium,” Bae’s exhibition featured an installation called ‘Speech, Thought, Meaning’, which comprised a parrot and five cubic globes as well as a four-channel film installation titled ‘Abstract Verb: Can You Remember Me?,’ featuring a passionately dancing man in bird feathers.

Yang Fudong’s Surrealistic Filmscapes

Born towards the end of the Cultural Revolution, during which freedom of expression was severely restricted, Yang differs from China’s first generation of media artists and cinematographers, who suffused their work with scathing social criticism. Instead, he opts for beautiful films that depict multi-layered reflections on China’s history and social conditions through rich artistic expressions. Yang has combined unconventional cinematography, painterly compositions, and poetic sensibility to become a preeminent experimental film installation artist and a pioneering figure in experimental Chinese cinema. As Walter Benjamin precociously fathomed, films occupy a medium of infinite imagination that transcends space-time barriers, as they replicate a particular period or event from the past and bring them before the eyes of a contemporary audience. The most alluring aspect of film is that good acting and mise-en-scène can reconstruct a time period and location that is liberated from space-time restraints, forming a theatrical simulacrum that eliminates the boundary between reality and mimicry. Visitors to the Daegu exhibition are greeted by the gripping imagery of “The Nightman Cometh”, a perfect illustration of film’s ability to construct a separate reality.

“The idea of yingxiang [an image] has a lot more freedom and allows for more possibilities. It is a journey to experience, an exploration, but not a finished piece like film.”1)

Left) Yang Fudong, ‘The Light that I Feel’, 2014, 8-channel video installation, 8~14min

Left) Yang Fudong, ‘The Light that I Feel’, 2014, 8-channel video installation, 8~14minRight) Yang Fudong, ‘Seven Intellectuals in Bamboo Forest ’, 2003-7, photo, 120×180cm

Right out of college, Yang became fascinated with film making, and the aim behind his work on “An Estranged Paradise”(1997) was to create “a legitimate film.” Yet this would be Yang’s only work to have a conventional cinematic narrative for screenings in theaters. While working on his most famed title, “Seven Intellectuals in Bamboo Forest” (2003–2007), which is composed of five installments shot over a five-year production schedule, the cinematic structure present in “An Estranged Paradise” gradually dissipated. Rich in elements common to painting, Seven Intellectuals in Bamboo Forest emphasized montages, and did away with scripts and dialogue. He approached the production process with idea of creating “abstract film,” “structural cinema,” or “sensory cinema." 2) He wanted his film to be an abstract work without clear definition, relying on structure and expression over concrete depictions to expand interpretative freedom. 3)

“In ancient Chinese painting, there has always been an emphasis on liu bai – what’s left undrawn on the paper. For me, no matter whether I am making a video or a film, the same idea applies… The undrawn part in a work is there for the audience to engage with, using their imagination for viewing and interpretation.”4)

By not revealing the artist’s intentions and freeing his work from definition, Yang gives the viewer room for imagination, forming his foundational concept of “abstract film,” which he has labeled “installation film,” “spatial film,” “mind film,” and “sense film." This concept has allowed him to create an entirely autonomous repertoire of what can be called “meta-film.” Effective use of montage is essential in producing a profoundly abstract quality. The abstractness of his work also comes from an exotic and foreign quality, and his montages of various shots blended together blur all spatial and temporal permanence. These surrealistic and artistic qualities are magnified in his mainstream-channel installations and color films.

An eight-channel video installation that occupies the entirety of UMI Hall, “The Light That I Feel” (2014) is a bold new experiment that prioritizes the meeting point between his artwork and the viewer. To screen each channel, he built eight wooden installations that resemble miniature theaters, with the film being played on screens affixed to both the inside and outside surfaces of each installation.

When inside the structure, viewers are forced into intimate settings that place them face to face with one film. When outside, they can see a multi-screen arrangement, where all eight films interact in the same space. “The Light That I Feel” merges installation art with cinema to craft a unique space where the viewer and the artwork interact, distracting or forcing one to focus.

Yang Fudong, ‘ New Women II ’, 2014, 5-channel video installation, HD color, 12min~15min 47sec

Yang Fudong, ‘ New Women II ’, 2014, 5-channel video installation, HD color, 12min~15min 47sec

Platform-L exhibited the color film “New Women II,” the pinnacle of Yang’s abstract cinema. Borrowing from the aesthetics of 1920s and ‘30s Shanghai cinema, Yang spotlights the abstract beauty of what’s being depicted and expresses the transcendent nature of time. His first high-definition color film, ‘New Women II,’ features women wearing vintage swimwear, and is reminiscent of the artificially picturesque feel that pervaded the first color photographs.

“It’s not a real image from Shanghai in 1920s but a fake, and I wanted it to look fake,” 5) says Yang. He plays with cinematic “artificiality” by utilizing a fake beach, an unrealistic set, and partitions of translucent colored slabs that look like cellophane. In the original “New Women,” Yang incorporated the avant-garde art of Shanghai in the ’20s, but for its sequel, he hoped to portray the “disparity between dreams and reality in the digital era.” Article in above footnote Within the artificial space, Yang juxtaposes beautiful Asian women against a set that evokes Western surrealism and vanitas still lifes, drawing the viewer into a world of dépaysement (disorientation in a foreign land) and the uncanny.

Yang desires to incorporate the realness of unexpected situations that occur when shooting a project without a script. Improvisation creates unexpected surprises, a creative process that is difficult to realize through predetermined design and meticulous planning. As opposed to the blank spaces, places of contingency, that he offered before, ‘New Women II’ inundates the viewer with an endless stream of colors and sensations. Visitors stepping into the exhibit are confused as to which of the five screens, placed in all directions, they should be looking at. The flood of images and colors on every screen is interminable, without beginning or end. Placed in such a confounding unreality, viewers have to decide how to approach what they’re seeing and how much time to spend in the gallery. Viewers have to adopt the role of the film’s second director the moment they walk in.

Left) Bae Young-whan, ‘ Speech, Sound, Meaning ’, 2016, Mixed media, 210×225cm

Left) Bae Young-whan, ‘ Speech, Sound, Meaning ’, 2016, Mixed media, 210×225cmRight) Bae Young-whan, ‘Babel-I’, 2016, Sound installation, 50×230cm

Bae Young-whan’s ‘Land of Birds’

Born in 1969, Bae Young-whan grew up amid Korea’s floundering democratization, when neo-liberalist policies were intruding on individual liberty. According to his own words, Bae has spent his entire life in voluntary alienation: half of it as an artist, and the other half in listless incompetence. Since his oeuvres show someone who spent his chaotic youth confronting himself and the society around him, it seems obvious that Bae’s work is in defiance of today’s societal hypocrisies. His work speaks of the cries of marginalized people amid the inequality that plagues capitalistic societies; a cruel, money-worshipping world that has placed a price tag on everything; citizens who have become complacent and domesticated by corrupt bureaucrats who pacify and repress under a banner of public welfare; and the children forced to feed the status quo. A single look at the titles in his repertoire reveals the direction of Bae’s gaze: “Song for Nobody” (2012) depicts a world that caters to the haves and rejects the have-nots; “The Homeless Project: On the Street” (2000) focuses on the living products and symbols of inequality; “The Way of Man” (2005) speaks for those who become collateral damage in a world of endless competition; “Library Project Tomorrow” (2009) extends its hand to culturally estranged children; and “the Insomnia series” (2008) features a flashy chandelier that is made from the waste of consumption and instant gratification.

“Pagus Avium” is an exhibition that continues Bae’s tradition of social criticism and his reflections on the marginalized and alienated. Upon walking into the gallery, visitors are greeted with “George Orwell Walking in the Bentham Village” (2010), which is small but saturated with visual symbols, a work that looks complex at first but is actually a depiction of everyday life. The village emits an incomprehensible whirring sound that is blasted by a hanging bundle of loudspeakers, “Barbell-I” (2016). In the middle of everything is a giant parrot, with its face covered by a hat, standing as if in observance. Five cubic globes are scattered around the parrot, forming a piece titled “Speech, Thought, Meaning” (2016). Birds in Bae’s work have always been caged and serve as metaphors of human greed, self-portraits of the modern human, who has degenerated into a mere target of surveillance and control. The bird in “Pagus Avium,” however, is a parrot of silence. With its face and eyes covered, the parrot cannot perform its usual role of repeating what humans say, for it is bombarded by worlds of incomprehensible words. The parrot either does not know what to say or has taken a vow of silence. Its silence represents a world of infinite words that teach nothing and cannot be understood or repeated. It is a critique of today’s excess of words and noise, and in many ways a self-portrait by Bae. Perched upon a clothing rack marked with ruler-like gradations, the silent giant parrot and its sealed beak are an introspective reexamination: Just how effective are social criticism and all the world’s protests and demands for reform? Although at a loss for words, the parrot still seems to possess self-awareness, which is detectable in the spontaneity of its silence. That spontaneity is reminiscent of Bae’s way of rebelling against a world of chaos, the fierce determination with which he spent half his life in art and the other half in listlessness. Yet words still have their limits. Words may be able to expose a problem and report it, but they cannot lead the effort to fix it.

Bae Young-whan, ‘Abstract Verb-Can you remember?’, 2016, 4-channel video, 6min 37sec, installation view at Platform-L

Bae Young-whan, ‘Abstract Verb-Can you remember?’, 2016, 4-channel video, 6min 37sec, installation view at Platform-L

Taking words’ stead, ‘Abstract Verb: Can You Remember Me?’ offers a solution. It calls for action, the discovery of something beneath the surface of movement. The dancer dressed in a bird’s feathers is speechless. The dancer simply moves dynamically, ecstatically, with the music. Engrossed by the exhilarating music and the dancer’s rhythmical movements, the viewer is also made speechless. The paths of the bird’s movements are like those of a shaman in mid-exorcism, shaking off evil spirits. What is it to purify by dancing ecstatically, as opposed to using words that are conceptual and cerebral? Perhaps it is the “abstract” part of the “verb” that Bae is referring to, the ailments that plague our world today: inequality, repressive education, disregard for human life, materialism, and social Darwinism. The bird’s dancing determination to shake off all the world’s hypocrisy and suppression is none other than a physical expression of the land that Bae seeks. Movement rich in sincerity, Bae seems to suggest, is a new means by which one can and should go from words to action, and from the “land of birds” to the places beyond. ‘Abstract Verb: Can You Remember Me?’ is a physical ritual, a call for modern humanity to recover the tangible and primordial power of motion that we have lost.

Their Dreams and Their Narratives of Salvation

The works of Yang and Bae have their disparities, yet both speak of a path to redemption. They both resist an existence that is bogged down by authoritative oppression, jungle-law capitalism, and surveillance in the name of public safety, and they both dream of a new, better world. In An Estranged Paradise and Seven Intellectuals in Bamboo Forest, Yang wanders in search of a new world but ends up where he started. He has completed a roundabout journey, with the new world nowhere in sight. He does not provide any concrete answers for building a new world, and in case of the New Women series, dives even deeper into the abstract and sensory. In that sense, he’s quite ambiguous, but it seems that he’s seeking a spiritual utopia. Bae is still reluctant to return to his starting point. Still invested in today’s social problems, he hungrily searches for solutions. But this disparity between the two artists is more rooted in the scope of artistic freedom that their respective societies grant. It isn’t necessarily reflective of a contrast in their aesthetic and historical values or their social awareness as artists. They’re both products of the societies into which they were born, walking the paths that they’ve been granted.

Deliberating on current phenomena and problems in contemporary societies, where the realization of sincere channels for communication and reconciliation is impossible through mere words, both the Korean and Chinese artists have searched for therapeutic options and treatment methods. In the end, the worlds they dream of meet at a certain point. That point is the world and sky of Yang, the surrealist aesthete, and the world and sky of Bae, whose human birds fervently struggle to shake off the world’s shackles and distorted standards and take flight.

1) Yang Fudong interviewed by Christen Cornell, Artspace China, University of Sydney,

http://blogs.usyd.edu.au/artspacechina/2011/04/interview_with_yang_fudong_by_1.html

2) “Twin Tracks: Yang Fudong” (Shanghai: Yuz Museum, 2015), 41.

3) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mGUIv4BFHw, accessed on July 20, 2016

4) http://betweenthescreens.acmi.net.au/chapter4.html, accessed on July 20, 2016

5) http://news1.kr/articles/?2657844, accessed on July 20, 2016

6) Ibid.

LEE Phil / Art Historian and Critic

She is an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Fine Art at Hongik University. She holds a Ph.D. in Art History from the University of Chicago. Her essays include: “Jung Kang-Ja: A Pioneer of Korean Experimental Art of the 1960s and 1970s”(Routledge, 2021) and “Jungjin Lee: The Trans-territorial Photographic Tableaux” (Spector Books, 2018). She is an editor of Dansaekhwa 1960s-2010s: Primary Documents on Korean Abstract Painting (MCST&CAMS, 2017).