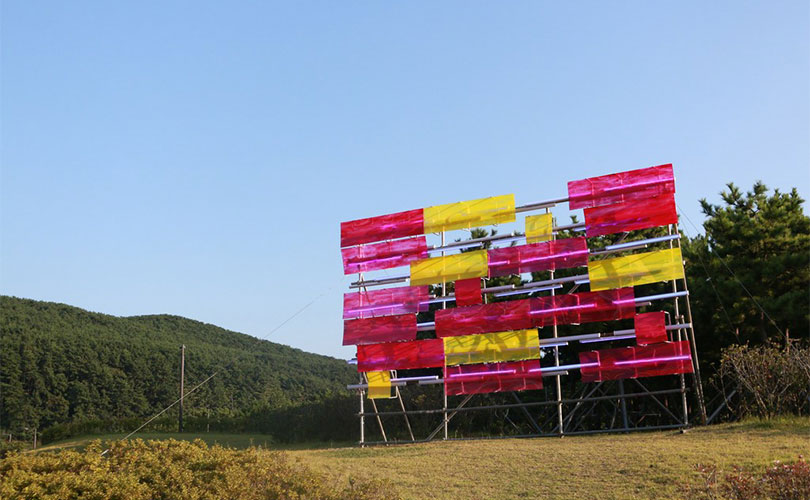

Paul Schwer, Billboard Painting Busan, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

Paul Schwer, Billboard Painting Busan, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017 The encounter of the sea and art

The past three decades have seen the Sea Art Festival grow into a major cultural and art event of the Busan area. Starting in 1987 as part of the cultural festivities celebrating ’ 88 Olympic Games in Seoul, the Sea Art Festival was held every year until 1996, and from 2000 to 2010, it underwent a change as it was integrated into the Busan Biennale. Since 2011, however, the festival has been held every odd year as a separate event, which was part of an effort to develop it into an independent cultural brand. The festival has exhibited artworks at all of Busan’s major beaches, including Haeundae, Gwangalli, and Songdo, a characteristic of a “seaside” art display; in 2015, it attempted to make another change when it chose to hold the event at Dadaepo Beach in the southwestern part of Busan, a relatively marginalized region in terms of cultural arts. The Sea Art Festival has gained a degree of reputation as a cultural asset of Busan during its 30-year history, but it seems to make continuous efforts to find possibilities and opportunities in which art can contribute to the region as well as the wider society.

It is remarkable that this year’s Sea Art Festival is held once again at Dadaepo Beach since the Busan Metro Line 1, which was newly launched at the beginning of this year, has increased the accessibility to the venue; it is also noteworthy that the Sea Art Festival, despite its affinity with the “sea,” increasingly intendeds to promote “public art” in the form of the region’s local culture and art development and urban regeneration. For example, ninety-four works out of the entire collection presented at the festival have been donated to and are owned by the Biennale Foundation of Busan, and then the foundation reinstalled them around downtown Busan, providing local residents an opportunity to enjoy art more easily in their daily life.

Felix Albert Bacolor, All a man can do is look upon it, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

Felix Albert Bacolor, All a man can do is look upon it, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017 If these artworks, moved away from the sea, are to resonate among local residents serving as true “public art,” rather than being planted in the city under the pretext of promoting “public art” despite its disharmony with its urban surroundings, the forms and characteristics of the artworks displayed at the festival are a crucial factor. The reason why the installations presented during the festival didn’t exclusively follow the theme of the exhibition’s location may be because the festival’s organizing committee also considered the prospects of the works after the event. Maybe that’s also why the artworks at the Sea Art Festival 2017 highlighted their qualities of plastic arts more prominently, rather than focusing on the site-specific themes such as the sea and nature. The sea served as the site for artwork installation, an open space that provides easier access to a wider range of viewers.

What message did this year’s Sea Art Festival attempt to convey through the works which “slightly” departed from their intrinsic themes involving the sea and nature? “Ars Ludens: Sea+Art+Fun,” the theme of the 2017 Sea Art Festival, will provide a clue.

Playing humans and playful art

The bold slogan of the Sea Art Festival 2017 is “fun.” As explicitly expressed in its theme “Ars Ludens: Sea+Art+Fun,” fun or amusement are the most important concept that cut across this year’s event. Johan Huizinga (1872–1945), a Dutch cultural theorist, stressed in his book Homo Ludens (1938) that one of the attributes of humans is “playing,” defining the playful traits of human culture.

Left) PERBOS, Floride, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

Left) PERBOS, Floride, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017Right) DO YOUNG JUN, A slice of summer, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

Borrowing from the phrase “homo ludens,” meaning “playing humans,” Ars Ludens is a reflection of the festival’s idea that art created by “fun” humans is laden with playful traits. Here, one has to be careful not to overlook the fact that fun is not a concept that is in contrast with labor, but it derives from the entwined, harmonized relationship between labor, nature, daily life, and leisure. In other words, both the artists who create artworks and the local residents who view their works need to regain the intrinsic amusement derived from art by presenting the artwork in a natural environment such as the seaside, which is also a part of their daily lives. At the Sea Art Festival 2017, the forty-one artists (and collectives) participating from eleven countries (nineteen Koreans, fifteen international artists, and seven special teams) focus on providing a variety of fun experiences with the viewers based on such a premise, revealing the “playful” nature of art in various realms such as nature, daily life, and visual entertainment, along with highlighting the characteristics of the sea, the site of the exhibition.

The artworks displayed on the beach showed their most distinctive characteristics in bright colors; the artists didn’t hesitate to use artificial colors and materials, in stark contrast with the natural surroundings, drawing instant attention from the viewers. Such works included Paul Schwer’s Billboard Painting Busan, which greeted with the visitors from the ecological park at the entrance of Dadaepo Beach, Laurent Perbos’s Floride, Jeung Take-sung’s Colorful Bomb and Shane Bradford’s Agalma Two Halves all presented on the beach. In some aspects, such artificial artworks could prevent the viewers from enjoying the scenes of the nature, but there’s no absolute need for the artworks displayed in the natural environment to perfectly blend with their surroundings to create a harmony. The meaning of presenting these works at Dadaepo Beach, in the midst of its well-preserved natural surroundings, is all the more significant, considering the piece’s critical messages against urban and economic development at the cost of the destruction of natural ecosystems, or the ecological degradation caused by indiscriminate development of nature. In the same vein, other works such as Subodh Kerkar’s Moses and the Plastic Ocean, which highlights ocean contamination caused by reckless plastic use, and Felix Albert Bacolor's All a Man Can Do Is Look upon It, where the confrontation between human greed and nature are expressed through a white whale hanging from an industrial crane, convey the same message.

DM Turtle Stone, Play of Language, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

DM Turtle Stone, Play of Language, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017 One of the functions offered by art is to provide the viewers new experiences by reinventing familiar objects used in daily life into a unique piece of art. Extremely ordinary, everyday objects tend exist without notice in daily life, but their values are too significant to limit their use only to the frame of ordinary, everyday life. In this regard, enlarging the size of objects to present them from a spectacular angle could be one artistic expression, and the different sensation brought by the enlargement creates a sense of amusement generated by the visual experience. For example, works that attracted attention from the viewers in this respect include Lee Ki-soo’s Besom, in which the trivial twig broom, magnified to a giant scale, sweeps the beach, and Kim Tae-in’s Accidental Inflation, where a giant figure sculpture made of metal is pumped full of air. Kim’s work especially drew a bittersweet smile from the viewers when the artist explained the figure was designed to depict ordinary fathers in today’s world who would wait for their children holding a balloon, an overlapping image of numerous “heads of household” who would visit the Dadaepo Beach as such. Installations expected to become major photo zones, offering fun in terms of their scale and shape, include Do Young-jun’s A Slice of Summer, in which pieces of watermelon are installed on the beach sand; Hong Won-chul’s Mechanized Human and Mechanized Poodle, a series of sarcastic observations of mechanized modern society through giant poodle and human figures; and Anywhere, an artwork resembling a giant blue crab made through a combination of numerous brightly colored doors by D-art, a special team from Dong-A University.

Nevertheless, the “sea”

Nevertheless, it is still a shame that the works presented at the Sea Art Festival 2017 rarely showed site-specific elements regarding the sea as the exhibition site or particular observations on nature, unlike those displayed at the previous exhibitions.

Left) Subodh Kerkar, Moses and the Plastic Ocean, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

Left) Subodh Kerkar, Moses and the Plastic Ocean, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017Right) Tae In Kim, Accidental inflation, 2017

Despite its official theme of “fun,” the Sea Art Festival boasts its biggest originalities and charms as a seaside exhibition where visitors come to the sea themselves in order to view the works while enjoying the scenery of the sea, wind, waves, sand, and clouds. In this year’s festival, the “sea” was expanded into a larger concept as a space in which “imagination is realized,” rather than a physical space, and the artworks were displayed in such a space. However, the works that left an impression on me, even long after the show, were the ones that set their scenes in nature and created a harmony with it. This is a proof to my argument, exemplified by works like Kang In-goo’s Rocks, Meet the Sea, where the natural stones and pebbles collected from streams were gathered together, creating an opportunity to contemplate artistic action and the power of the nature, and DM Turtle Stone’s Play of Language, in which a mix of sound derived from the wind and the scenery echoed around the sandy beach. Sea Cube, a collaborative work by Ohashi Hiroshi and Ha Myoung-goo, involved burying a two-ton metal cube with its surface installed parallel to the sandy beach and filling it up with sea water, in an attempt to materialize the wholesome presence of Mother Nature, which goes beyond our knowledge and reach. However, the installation crept above the beach sand little by little because of the flux and the reflux of the tides, transforming the work into a different one where the artist instead recorded the process on the metal walls of the cube, unlike his original intention. Watching over the piece of work “sacrificed” by the nature, I once again fully realized that in the end, any man-made art has no choice but to succumb to the power of nature such as the “sea.”

JUNG Hye-ryun, A Line of the Projection, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017

JUNG Hye-ryun, A Line of the Projection, 2017, Commission for the Sea Art Festival 2017 Yet again, the sea provided an open space where visitors to Dadaepo Beach and journalists participating in the festival’s press tour listened to the curator speak about on the artworks. I was more curious about the visitors’ response than the explanations, so I closely watched the expressions appearing on their faces and conversations shared between them. A couple looked at each other, saying, “It’s so fun!” after the press tour was finished. That’s right. Art should be also fun. It was a shame that only a relatively small number of works were displayed in contrast to the vast space of the sea—I assume it was partly because the festival organization considered reinstalling the works across the city of Busan after the event as part of an urban regeneration project—and that there were only a few environmental art pieces that touched on the issue of nature. However, I could still feel the power of the Sea Art Festival 2017 as I watched the visitors come to the beach even before the official show began, gathering together and walking around the area to view the installations. I recommend paying a visit to Dadaepo Beach in Busan after Tropical Storm Talim is gone. Whether the visit is for the exhibition tour, a sightseeing trip, or a surfing—I actually saw many people enjoying the surfing despite a chilly weather when I visited Dadaepo Beach—we all will have fun. Because we humans are homo ludens, even before the existence of art.

References

Ironically enough, the Sea Art Festival 2017, with its focus on fun, was characterized by various academic and cultural programs that directly dealt with the theme of the exhibition, including artists talks, open seminars, open-air Agora Lectures, and matching programs. The festival’s intention to echo contemporary narratives of modern art, as well as focusing on the amusing elements of art, was revealed in its five programs run through the eight sessions on how the exhibition theme was expressed in the displayed works and how to explore such a theme in the narrative of “fun.” Detailed information on the theme is available at the official website of the Sea Art Festival 2017 (www.busanbiennale.org).

※ his article was originally published in MisulSegye magazine (October 2017) and reprinted under authority of a MOU between KAMS and MisulSegye.

Chang Seo youn / Art journalist, MisulSegye

Chang Seo-youn graduated Hongik University with a Master's in Art Studies and currently works as an art journalist at monthly magazine MisulSegye. She co-organized an art exhibition “Analytical Index” (2015), and also participated in the Korea Art Week program titled “Interlude” at Insa art space (2016).