Those born in the 1970s are likely to find themselves more comfortable at Lim Minouk’s exhibition, 《The Promises of If》. It was at this time that the Scholastic Achievement Test was amended to the College Scholastic Ability Test. The live TV show titled, 『Finding Dispersed Families』, presented by KBS in 1983, was a special broadcast aimed at finding and reuniting about ten million people belonging to families that were torn apart by the Korean War and the subsequent division of the country. The program was broadcast for five consecutive days, and was shown in place of all other regularly-scheduled programming, including soaps and cartoons. Every broadcast a melody would play, starting with the words, “Does anyone know this person?”, launching the country into a collective search. Even viewers who were not of a dispersed family, fixed their eyes on the television screen, laden with the unspoken responsibility of helping dispersed families reunite by keeping their eyes peeled on their surroundings. In this work, Lim focuses her attention on the memories and stories of people separated from their loved ones, their pain, and the political and social circumstances that inflicted it upon them. The images shown in these works were created using a mixture of latex, wax drippings, feathers, bone fragments, and other materials. This work shows that the artist is still keen on collecting ‘clear evidence that proves the truth,’ similar to that of documentarist, while also displaying characteristics of an ongoing artist, perfecting a series, like a perfectly constructed full-length novel.

|

Lim Minouk Lim Minouk studied Western painting at Ewha Womans University before moving to France where she received the Diplôme National Supérieur d’Arts Plastiques (DNSAP) cum laude at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (ENSBA) in Paris. Lim has held various solo exhibitions including 《Lim Minouk – general genius, Gallery Veronique Smagghe》 (1997) in Paris; 《Subjective Neighbors》 (2000) at the Insa Art Space in Seoul; 《Jump Cut》 (2008) at the Art Sonje Center; and 《Longing for Slight Fever》 (2013) at the Art Center Nabi COMO, SKT Tower, and 《The 》(2015) PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art. She has also participated in various art events such as exhibitions, performances, and projects, both in Korea and abroad, including 《United Paradox》 (2015, PORTIKUS, Frankfurt, Germany) and 《PROSPECTIF CINÉMA》 (2017, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France). Currently, she works as a professor in the Department of Fine Arts, School of Visual Arts, Korean National University of Arts, where she teaches in tandem with her that the complexity and anxiety generated during artistic activities are caused by a sense of humility coupled with reckless defiance against the established truths, what is unknowable, and the wider world. |

Panoramic view of 《New Town Ghost GAGAHOHO – Lim Minouk Solo Exhibition》, 2017. DAAD Gallery, Berlin, Germany. ⓒ the artist

TEXT : Jung Iljoo (Public Art, Editor-in-chief)

PHOTO : Courtesy of & Provided by the Artist

1. 〈Gates of Citizens〉, 2015. Steel (ruined remains of a shipping container), sound, 517 × 410 × 288 cm. Panoramic view of 《The Promises of If – Lim Minouk Solo Exhibition》, PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul. ⓒ the artist.

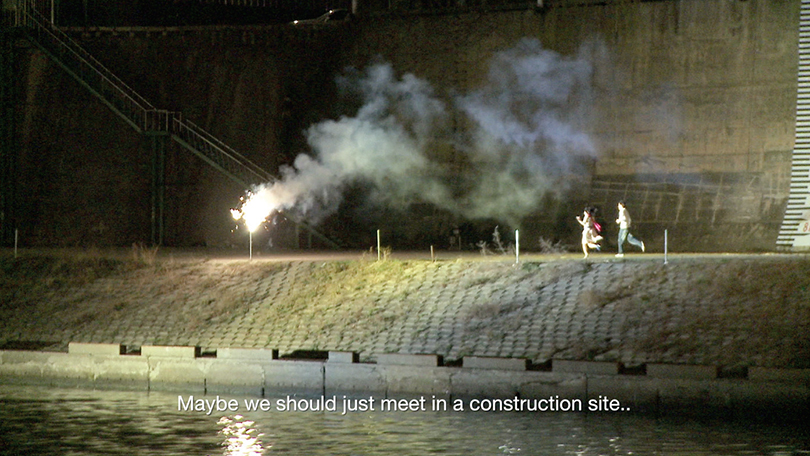

2. 〈Running on Empty〉, 2015. Panoramic view of 《The Promises of If – Lim Minouk Solo Exhibition》, PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul. ⓒ the artist.

We are now being drawn once again to the subject of‘dispersed families’ yet the hazy, impactful memory that still remains from 35 years ago, is shared among Koreans, now in their 40s or older. This serves as the very reason as to why the works of Lim Minouk are interpreted differently according to each generation of viewers, among whom members of the older generations recollect the tragic war, as well as the grief it inflicted on so many families. Her works remind viewers of a theater filled with the terrible sound of the lamentations of families torn apart by the war, be it mothers and fathers, wives and husbands, brothers and sisters, or friends and neighbors, in honor of those that had lost their lives.

For younger viewers, her works appear more like a thriller film in which all the protagonists are suffering from some unknown source of terror. They are, of course, sufficiently aware of the background to these works, hence feelings of awkwardness or discomfort, while others try to accept the solemn atmosphere in a more positive light. The diversity of viewer response is exactly what the artist had intended. To the question, “What do you consider to be most important when constructing an artwork?”, she simply answered, “Discord,” before going on to explain that she deals with the theme of landmark turning points between the individual and the rest of Korean society while promoting a sense of positive attitude amid self-interpretation among viewers through unfamiliar and unrefined works.

I asked about her ultimate intention in creating works capturing the lamentations of what has disappeared, as well as the restoration of memories. She replied, “Isn’t it kind of like the sense of distance or connection created by our yearning for something to never disappear? I am interested in how something so uncertain, beyond the state of disappearance, continues on, and remain doubtful about the relationship of a community formed on the basis of that, and where the subject of “I” fits into that equation. These doubts lead me to form a relationship with creative practice. You can understand humans and their society by examining into how they have handled the emotion of fear derived from separation and non-existence.”

〈The Possibility of Half〉, 2012. 《Korea Artist Prize Exhibition》, MMCA Gwacheon, Korea. ⓒ the artist

Lim has been successful in attracting the attention of the Korean art world through a series of provocative works presented at special events held since her return from France in 1998. Her work presented at the 《Gwangju Biennale 2014》 made a particularly strong impression upon art lovers. At this biennial international art event, her work, instigated a chaotic atmosphere by disrupting viewer movement with the arrangement breaking the boundary between the work itself and its viewers. Presented live via the internet, her work started with two shipping containers running along a highway carrying the remains of Korean War victims to Gwangju and, along with them, Korea’s modern history of ideological conflict, war, and national division. The containers finally arrived at the center of the Biennale Hall Plaza in Gwangju with the remains of war victims yet to receive proper burial or homage. Their arrival was then followed by the reception of both surviving family members of civilian victims of the massacres that occurred during the war, and a group of Gwangju citizens, who had lost their loved ones during the May 18 Democracy Movement in Gwangju. As the containers carrying the remains of war victims and the buses carrying their bereaved families were escorted by a police helicopter and ambulances, they were enclosed almost instantly by a large amassing crowd of participants and visitors to the biennale, in addition to tenacious members of the press, creating volcanic turmoil all around. I was there in the middle of the venue, but had to rely on a streaming service provided by a web channel to appreciate this strange work of art.

It was a ground-breaking work for the artist and the viewers as a whole. The preparations for the work led her to the massacres of civilians during the Korean War, the process of formation and dissolution of communities in a history without end, the importance of the venues, and the role of the media. It was then that a memory suddenly flashed through her mind of the dispersed families broadcast in 1983. She thought to herself, ‘The subjective perception of self, or the change of standards, by people with secrets, people unprotected by the state or law and who therefore remain alienated, is closely connected with the artist’s aesthetic practice.’ The standard that would then come into play was that of ‘lamentation.’ She started to pay attention to the narratives of people who had left their home in the north to settle in the south, resulting in her work, .

〈Navigation ID〉, 2014. Live streaming presented for the opening of the 《10th Gwangju Biennale: Burning Down the House》

〈FireCliff 2 – Seoul〉, 2011. Venue-specific Performance, Documentary Theater, International Dawon Art Festival 《Festival Bo:m》, NTC Korea, Seoul. ⓒ the artist

The installation work titled , which was displayed at the 《Busan Biennale 2018》, is also focused on the subject of dispersed families. Consisting of objects once displayed at a broadcasting station by dispersed family members in a bid to find their loved ones, the work creates an expansive horizon of lethargy, a sad landscape filled with poverty and exhaustion, and humanity praying for something in earnest. This was accomplished through changes that occurred according to different perspectives and moments of view. The artist piled up objects that once occupied television screens and images of people pining for their missing family members to make statements about ‘the loss of loved ones’ and ‘the pain left by the war.’

The works created by Lim Minouk crosses the boundaries between art genres freely in order to tell more stories. As for the use of the word, ‘spectacle,’ to define or describe her works, she explained, “The multiple layers and complex settings are designed to emphasize the importance of installations as theatricality and the environment, and are a result of my resistance to minimalism. It perhaps stems from my approach of avoiding the concept of genres altogether. Furthermore, my installations are based on my interest in the childishness we witness in many children’s games, which gives way to my argument that my works stand outside the sophisticated grammar of modern art. I want to be further away from that scope while enjoying a greater sense of freedom.”

〈Portable Keeper〉, 2009. HD Single Channel Video & Sound Projection, Video Still Image (Running time: 12 m 53 sec), Variable Installation. ⓒ the artist

For those of us living in Korea following the war and division on the peninsula, two kinds of histories exist: one is the official history which is already determined, and the other is the history which continues to be revised. In this environment, some artists try to identify aspects of history that have been excluded from the official narrative and the people who remain absent from the prevailing narrative. The current situation formed by the history of familial separation and missing people has inspired the artist to explore a new area for her works in the future. “I am currently exploring, through song, the ambiguity of universality and totalitarianism, its psychological territory, and roots. The fir tree can be seen throughout the world, utilized as the symbol on a red flag, as part of a national anthem, as simply a pine, and a symbol of Christmas.

In Asia, however, the pine tree serves as an apparition of loyalty and fidelity, amid the history of violence and oppression. This clear differentiation is then used to turn it into a performance in order to raise questions.” In an effort to find the answer to existentialist questions about facts and identities, she subsequently presented the performance, , on September 30 in downtown Tokyo by using poll campaign vehicles and bands, while broadcasting it on the Internet.

Upon the end of the interview, she said, “Lim Minouk is a pathetic, yet grieving artist.” We easily turn away from our memories and from injustices because of a lack of capacity for memory or compassion, rationalizing, “It simply can’t be helped.” Lim Minouk is a little different, however. She maintains a cool and collected state as she laments memories she was never directly a part of while working to restore what can no longer be seen.

〈S.O.S.-Adoptive Dissensus〉, 2009. Venue-specific Performance, Video Documentation, HD Video and Sound Projection, Video Still Image. ⓒ the artist.

※ This article was originally published on a Monthly magazine, Public Art in OCT 2018 and reposted under authority of a partnership between KAMS and Public Art.

Jung Iljoo

Editor-in-chief, Public Art