Suki Seokyeong Kang. Courtesy the artist.

TEXT _ Stephanie Bailey

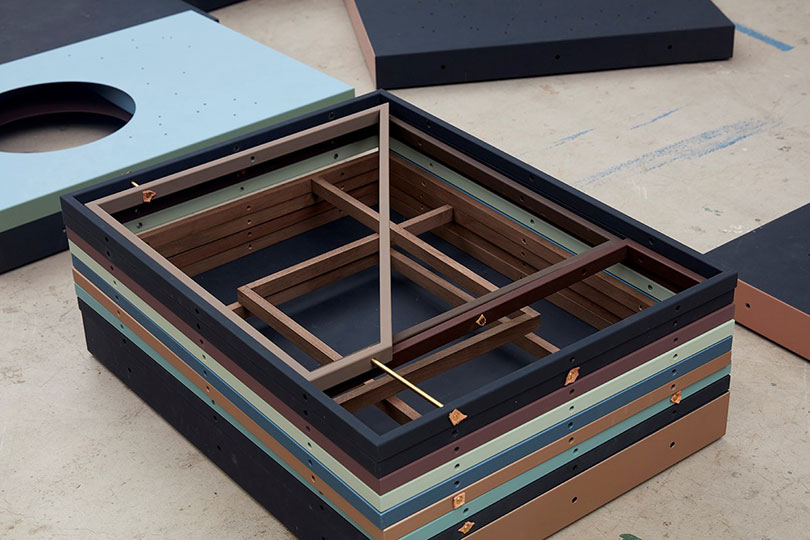

IMAGE _ provided by Suki Seokyeong Kang & One and J. Gallery

In June 2018, Suki Seokyeong Kang was awarded the 'Baloise Art Prize' at 《Art Basel》, alongside Lawrence Abu Hamdan: an annual award given to two emerging artists exhibited in the fair's Statements sector. Showing with One and J. Gallery, Kang presented an installation of abstract sculptures including 〈GRANDMOTHER TOWER–tow #18-02〉 (2018), composed of painted steel tubes forming three drum shapes with a triangle 'face', each perched on top of the other. 〈GRANDMOTHER TOWER–tow #18-02〉 stems from the ongoing series 〈Grandmother Tower〉. The first 〈Grandmother Tower〉(2010) comprises a stack of discarded dish racks wrapped in thread to create enough friction to produce a curved, freestanding stack assembled to mimic Kang's grandmother's posture and height. These sculptures honour a woman who was born in the 1920s, and lived through colonisation and the Korean War. As Kang explains, her grandmother always responded to questions about her life with answers that were 'oriented towards the future', and she encouraged Kang to 'focus on how to cope with the present in which [she] belong[s].'

The idea of systematising roles, bodies, temporalities, and gazes through the arrangement of elements within a given space is a thread that runs through Kang's practice, right down to the use of titles, which follows a calculated system of sorting. ('Each object has its own name, such as Heavy Round, and Warm Round', Kang notes; 'and when the units are combined, the works can be renewed with titles such as Round Cliff and Poking Square.') The grid is a guiding and organisational principle—something that is evident in Black Mat Oriole, a five-year research project (2011–2016) presented at the 《Gwangju Biennale》 in 2016, which explores the power and politics of space. It is also the basis for her exploration of 'Jeongganbo'—a musical notation system invented in the Joseon Dynasty in Korea that codifies the pitch of musical notes. Between 28 February and 7 April 2018, Tina Kim Gallery in New York presented Kang's investigation into Jeongganbo through her use of the Chinese character Jeong (井)—a visual reference to the musical notation's grid system.

Exhibition view: Sculptures by Suki Seokyeong Kang on view at One and J. Gallery, Statements sector, Art Basel, Basel (14–17 June 2018). Photo: Kyoungtae Kim.

Black Mat Oriole had its US premiere in 2018 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia (27 April–12 August 2018). The show included sculptural assemblages made from a variety of materials, including urethane-painted steel and polished wood, and a video in which these constructions are presented in a black box, with near-invisible bodies moving through, around, and with them—a three-dimensional visualisation of a composed picture plane. The exhibition launched with a special 'activation' performance by two choreographers on works inspired by the hwamunseok, a traditional handwoven mat whose cultural legacy stems from the Goryeo period, when the chunaengmu dance was performed on it. (About two metres long and wide, the hwamunseok serves as the physical boundary restricting the movements of the dancer—a restriction that Kang plays with when deciding on the specific measurements of her own mats.) Part of Black Mat Oriole is about honouring a dying craft, since hwamunseok are now mass-produced rather than hand-woven. To create the woven elements of her installations, Kang works with three female artisans traditionally trained to make these mats.

In this conversation, Kang reflects on the core ideas behind her projects, and discusses her installations at the 《12th Gwangju Biennale: Imagined Borders (7 September–11 November 2018)》 and the 《10th Liverpool Biennial, Beautiful world, where are you? (14 July–28 October 2018)》.

'Activation' of Black Mat Oriole by Hyeongjun Cho and Hongseok Jang. Exhibition view: Suki Seokyeong Kang: Black Mat Oriole, Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia (27 April–12 August 2018). ⓒartist. Photoⓒ Constance Mensh.

What are you showing at the 《2018 Gwangju Biennale》?

I am showing a new series called 〈Mat Black Mat〉 alongside a three-channel video entitled 〈Black Mat Oriole〉. This new series is combined with nine units from the series 'Mat 61 x 81' (2017–2018); each unit has a specific position, with the direction, angle, size, and structure acting as a notation for a pattern. The overall structure, which is positioned on the floor and the wall, serves as a form of painting in combination with the hwamunseok, with the angle of each Mat 61 x 81 depending on the hwamunseok's weight and length. This setting indicates how to contemplate the unique position and area of each set.

〈Mat Black Mat〉 evolves from Black Mat Oriole, which is based on the idea of encompassing one's weight and movement into a square grid or the minimal space of the mat. Each 'mat' in 'Mat 61 x 81' presents the smallest platform that could be activated by an individual, and the series follows a strict ratio. As a whole, the series considers the space provided to individuals in society, upon which each person can stand and sustain their own weight. The work is less focused on generating limitation as it is on expressing the persistent possibility of systematising roles in space through the body, its positioning, and the gaze itself.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Mat Black Mat 61×81 #18-03 (2018)〉. Thread, woven dyed Hwamunseok. 63 × 84.5 cm. ⓒartist. PhotoⓒKyoungtae Kim.

This idea of systematising the body through the form of the hwamunseok relates to the reference that you make to the traditional chunaengmu court dance in the Black Mat Oriole project, too. The chunaengmu is a dance that was performed by one person on a small hwamunseok, as a means to commemorate the arrival of spring, right?

Chunaengmu (春鶯舞), the conceptual foundation of Black Mat Oriole—is a royal dance conceived in 1828 by Prince Hyomyeong of the Joseon Dynasty, the last dynasty of pre-modern Korea, which lasted from 1392 to 1910. The name literally translates to 'the dance of a spring oriole', and it was originally known in English as 'the nightingale dance'. As a solo dance, a very rare form among Korean royal dances, 'chunaengmu' is a collection of extremely refined movements performed within the confined space of a hwamunseok mat. In the Joseon Dynasty, each dance was documented through letters, and 'chunaengmu' was portrayed in particularly poetic terms. Among such terms was the expression 'hwajeontae', which signifies the image of an oriole perched on top of a flower. When translated back into choreography, this poetic verse requires the dancer to clasp her hands behind her back and smile. This is the highlight of the dance, and is also a gesture that was very hard to witness in other court dances, since no dancer was allowed to open one's mouth in front of the king, let alone smile.

In the chunaengmu dance, the squared mat is a restricted space, which I translate into a platform in Black Mat Oriole: a representation of a limited ground in which an individual can express his or her own voice and movement. The conceptual foundation of this project is the notion of individual space. But while this idea of space allotted for each individual serves as the primary grammar of my art, it also addresses the social contexts and conditions of each individual life.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Black Mat Oriole (2016–2017)〉. Three-channel video, colour, sound. 8 min 46 sec. ⓒartist.

Could you expand on how 〈Black Mat Oriole〉 draws out connections between past and present?

When I apply the traditional performance of chunaengmu to our current society, it becomes about the movement and voice that an individual makes in order to sustain their life. The work is carefully structured with a concern for how each individual can move forward with history, worries, and anxieties that are situated in the vertical time of a person's life. The work is metaphorical—as an artist, I am working through the dilemma of existing in a society where history and the present coexist.

The minimal grid I employ in my own mats is infinitely expandable as the individual expands the range of her or his movements. The movements on the mat serve as the blueprint for other visual manifestations, including painting and installation. As the conceptual space expands, the materialised form of the visual objects that constitutes this project is also transformed and diversified. As such, the project is a series of developments driven by the movements of individuals as they constantly pursue a state of further expansion.

Activation' of Suki Seokyeong Kang's 〈Land Sand Strand〉, 《Liverpool Biennial 2018: Beautiful world, where are you?》 (14 July–28 October 2018). ⓒartist. PhotoⓒBrian Roberts.

How does 〈Land Sand Strand (2018)〉 at the Liverpool Biennial compare to Black Mat Oriole?

〈Land Sand Strand〉 shares the same departure point as 〈Black Mat Oriole〉, but it also signals a beginning. While I focused on individual space and movement in Black Mat Oriole, for 〈Land Sand Strand〉 I created a work through which to concentrate on conditions and surroundings where there is no clear boundary.

A new hwamunseok, called 〈Mat (2017–2018)〉, became an important setting—or 'land'—for 〈Land Sand Strand〉. On the hwamunseok, weaving and notation is composed and positioned as a constellation. This thought process derives from my cognition of painting as a 'land'—depending on the audience's movement, visitors can activate Land Sand Strand as both an exhibition space and a performative realm not unlike the space of the hwamunseok.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Black Mat #07 (2016)〉. Painted steel, steel bolt, plastic wheel. 61.4 × 81.4 × 8 cm. ⓒartist.

You have said that 〈Black Mat Oriole〉 started as a reflection on the size of 〈Black Mat (2016)〉, a rectangular platform lying on the floor that you have said was informed by the principles of painting. Could you talk about how painting fits into your practice?

In terms of my practice, I think of painting as a compressed methodology containing a multitude of thoughts on how a painting can be activated to embrace the space in which it is placed. By projecting painting into the space, I attempt to realise a form of spatial notation that aspires toward balance and harmony.

For me, reading and navigating a space requires an explanation of how I describe space as a form of painting. I began to study traditional Korean painting in Ewha Womans University in 1996, where I am teaching now. By studying the aesthetics, philosophies, and ideologies contained in my own cultural tradition, I was able to see the different ways of looking through the vast timeline between tradition and contemporary in vertical way, which also indicates how I see the difference between my cultural roots and the place on which I stand now, as a form of vertical orientation.

Literary ink painting generates a possibility to see the present, and to learn how to think critically about the present through an engagement with the past. For me, it is a tool to navigate the present with a literary way of thinking. Although I use the term 'painting', I consider the starting point of painting from a slightly different place. Instead of representing something that already exists, traditional Korean painting has more to do with how you use paper as a vessel for your thoughts. Painting, as both a visible and invisible logic in my work, is a manifestation of the grid and the many layers that constitute a representation.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Jeong on the Black Mat (2016)〉. Assembled units, painted steel, wood frame, plastic wheel, brass bolt, steel bolt, leather scraps. Dimensions variable. ⓒartist.

How does the square fit into this? It is a shape that occurs frequently in your work.

I employ the square unit in my art as the formal unit of a painting. Each square is a space embracing the movements and the voice of each individual, and as a set these squares operate like a visual system that seeks a balance that allows individuals to coexist. It is through this structure of logic that I explore the contradictions and conflicts in society, and try to build a structure of condensed harmony. I wish to portray the anxiety of the present while also nurturing a hope for the future.

It was through the 〈Black Mat〉 that I began to explore how paintings move and expand throughout a plane, and also how I could convey the sense of time that crosses through that plane.

How did spatial notation become such a core part of your artistic practice?

Since 2014, I have created a series of daily paintings called 'Mora', whose planes develop within the minimum ratio of 55 x 40 centimetres. I specifically chose these dimensions as they can hide a body or torso. In this work, paintings function as the space that embraces time and where narrative piles up. As the size of the painting expands, both two-dimensionally and three-dimensionally, so does the space of time and narrative contained within the frame.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Jeong (2014–2015)〉. Assembled units, painted steel, wood frame, wood wheel. Dimensions variable. ⓒartist.

How does this relate to the way you see painting as an act of creating spatial depth?

Since I produce all my paintings with the canvas laid down on the table—that is, the wood pane and stretched canvas with mulberry paper placed on top—the four sides of each painting hold the paint with the force of gravity. This way of production allows me to face the space of painting as if looking down a well.

The 〈Mora〉 paintings, which are actually bereft of painting, evolved into an idea for the 〈Jeong〉 series (2014–ongoing), which employs square frames called 'jeong (井)', meaning 'water well'. By removing image and surface, the frames become a manifestation of the grid, which in turn embraces the many layers that constitute a painting. Each frame does not only address the painting that explicitly exists as an artwork—it also addresses the movement of the people inhabiting the space that the work is placed in, the boundary between the work and another, and spatial divisions or interventions that occur in and around it. The square frames can be piled on top of one another, expanding their overall spatial existence both horizontally and vertically in a given room. Built of similar but different ratios, each frame functions as a tool that expands the space it stands on.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Jeong 1/4 Series (2016)〉. Dimensions variable. ⓒartist.

This returns us to the use of notation in your work, and how it manifests at every level, from the compositions of objects that make up various series or installations, to the historic references you make. The 〈Jeong〉 series is very much based on 'jeongganbo', a traditional system of musical notation, right?

Jeongganbo is a system of musical notation that was developed in the Joseon Dynasty by King Sejong, who also created the Korean alphabet called Hangeul. I was attracted to the structure of this notation system—'jeongganbo' notates not only the pitch and length of each note but also the gesture or action required of the musician to play each note. The lyrics are also written inside the square.

I understand this system as a method for a spatial attitude—one that indicates how to talk, sing, and situate movements and choreographies within a timely, rectangular space. Within each square, a condensation and harmony of various elements constitutes each note. This set of squares thus operates as a spatial construction of narrative and rhythm.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Black Mat Oriole (2011–2016).〉 Paintings, sculptures, video, installation. Exhibition view: 《Gwangju Biennale 2016: The Eighth Climate (2 September–6 November 2016)》. ⓒartist.

Could you elaborate on how you turn your works into series, and how they in turn manifest as installations or sculptural assemblages that combine objects with videos and performances when you exhibit?

It is a constant process of performing and moving the units of a given work. When I imagine how each unit can be placed, and how it might take a role within the space, I always think about how to assign time to still objects.

When developing these ideas, I conceived of the space of video as containing time, movement, and also restrained movement. And that 'space' is accompanied with a black rectangle consisting of time and narration, which I call a horizontal narrative. Video animates the art I make, and extends it to the next page of the story. The intention is that video operates as the platform to make and use the work, or to create a space of possibility, as well as to embody personal thoughts and voices.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Black Under Colored Moon (2015)〉. Full HD colour video with sound. 26 min. ⓒartist.

You did not start 〈Black Mat Oriole〉 with a preconceived outcome in mind. Could you talk about how this approach influences your practice in general?

A concern for how to convey meaning and direction through my work is always present. I often use the term 'evaporate' when I explain my works. Concepts and thoughts, as well as many branches that existed within the process of art-making, all 'evaporate' when the work reaches a certain point. The narration that 'evaporates' remains as an essence.

'Activation' is a word you use often to describe the functionality of your work. Has your definition of 'activation' changed or developed with time?

When I approach my art-making process, I consider looking and thinking as two starting points. Expressing how these two aspects 'do' and 'act' as a work is the least I can do as an artist. Also, to me, 'doing' does not end at finishing one work, but includes the process of continued research and efforts to make the work. Though some of my works convey the time put into the process of development and making, there are instances when it is unseen. Even if the process is unclear from the finished work, I hope my viewers engage with their own thoughts to find out what they need to do or think in order to interpret the work. The focus on the individual in my work is a precondition for finding out how we can protect our own hearts while relying on each other to walk forward together. —[O]

※This article was originally published in OCULA(https://ocula.com) on 18 SEP 2018 and reposted under authority of a partnership between KAMS and OCULA.