“I wanted to draw my mother, whom I love so much. I intended to focus on my mother’s life and thought that it would lead me to embody the life of female in the artwork. In 1990s, I finally closed the subject of maternity and began to directly reflect my story of a middle aged housewife from the middle class on my works, which is Pink Room Series.……I think articulating the subject of maternity is never simple, and feels very risky. Of course, I knew that expressing this subject could be more of the ball and chain to the woman. But I believed in myself. I was thinking, If you want to objectify it, then do it. I am ready to dispute.”

-

- Yun Suknam Yun Suknam was born in Manchuria, China in 1939. In 1944, Yun returned to Korea, a year before Korea's liberation from Japan. She studied English literature at Sungkyunkwan University, printmaking at Pratt Institute Graphic Center and painting at Art Student League in New York. Yun had her first solo exhibition at Fine Art Center (currently Arko Art Center), in 1982, and held many other solo shows at Kumho Art Museum (1993), Kamakura Gallery in Japan (1998), Ilmin Museum of Art (2003) and Hakgojae Gallery (2009). She participated the major exhibitions of Korean feminist art history including October Group Show (1985, Kwanhoon Art Gallery), From Half to One (1986, Min Art Gallery), Women and Reality (1987, Min Art Gallery), and 99' Women's Art Festival: Patjis on Parade (1999, Seoul Arts Center), and invited to international exhibitions including Venice Biennale Special Exhibition (1995), Biennale of Sidney (2000) and Gwangju Biennale (2000). Yun received Lee Jung Seob Award in 1996 and the Prime Minister Prize in 1997.

To Tell the Story of Women

When you first presented the artwork in early 1980s, the term “feminism” did not even exist in Korean art scene. What made you to adopt the story of women in the painting?

When I had the first solo exhibition in 1982 at the Art Center of Korean Culture and Arts Foundation (currently, Arko Art Center), I was unaware of the feminism but I was aware of being a woman. Back in the days of my beginning, I was living as a normal housewife, but it was not very meaningful to me. I had nothing to do after 11 p.m., which is the time I finish the daily routine as a homemaker. I started to question myself, “Should I live like this till the end? Who am I and Why am I doing this?” So I looked for something to focus on and found the calligraphy, which I dedicated myself for 4 years since I was 38. Then one day, the teacher said that it would take 20 years to be proficient at copying the master’s style of penmanship. The moment I heard it, I realized that this was not for me. I wanted to tell the story of mine. Therefore, I quit the calligraphy and started to paint. But isn’t it hard for anyone to reveal oneself for the first time? Painting the landscape and still object was almost meaningless to me, so I wanted to draw my mother, whom I love so much. I intended to focus on my mother’s life and thought that it would lead me to embody the life of female in the artwork. In 1990s, I finally closed the subject of maternity and began to directly reflect my story of a middle aged housewife from the middle class on my works, which is Pink Room Series1)

Left) Yun Suknam ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

Left) Yun Suknam ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtroRight) Blue Bell (detail), 2002, 2015 (front), Kim Manduk's Heart is the Tears and the Love, 2015, mixed media, h:300cm d:200cm (back) ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

The subject, which is mother and maternity, seems to be the beginning of women’s stories in your artworks.

My mother lived a very harsh life. My father died when I was in the first grade of high school. After the Korean War, the time was very difficult and she had to make a living without a place to live as well as take care of 6 children, which the last one was only 1 years old. Her life had a great influence to me. I always think about my mother and pay my respect to her. To me, the meaning of her sacrifice to the children does not end as “a sacrifice.” I think the maternity, in a broad sense, is to make a great effort to care and live hard for the other and not for the self, so that it can possess the power. I sincerely wanted to express the maternity not just as a sacrifice, but as the force and will to live.

Once, I told my mother that I would like to quit the school and get a job to help the family, then she absolutely opposed and enrolled me in the prestigious high school, which was overly expensive for us. She only graduated the elementary school for herself. I think my mother was not an extraordinary one and I believe there were many mothers like this at that time. So I questioned to myself, “If this is not just my mother’s story, where this relationship and power come from?” If I was only trying to paint my mother, I would have failed to work hard. As the result of contemplation on the feminine life, I featured many shapes of working women in my early works, instead of painting the personal face of my mother.

When I look back those paintings from now, I notice a kind of self-defense mechanism. On one hand, I was speaking about the maternal force, but on the other hand, I wanted to avoid the sacrifice, which is forced to women. The rough and frightening feeling of the painting may be the result of the thought I had at that time. I think articulating the subject of maternity is never simple, and feels very risky. Of course, I knew that expressing this subject could be more of the ball and chain to the woman. But I believed in myself. I was thinking, “If you want to objectify it, then do it. I am ready to dispute.”

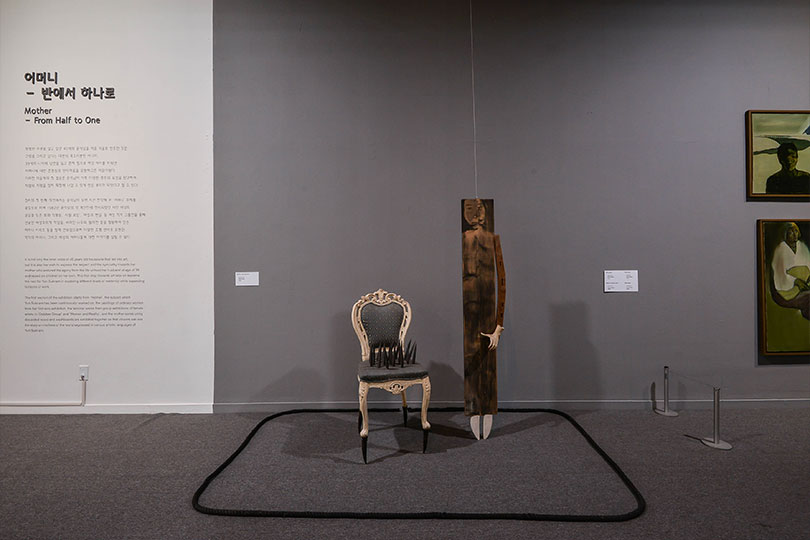

Yun Suknam's early works, exhibition view, Seoul Museum of Art, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

Yun Suknam's early works, exhibition view, Seoul Museum of Art, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

In 1985, October Group was organized by three women artists, including Kim In-soon, Kim Jin-sook and you. From this period, you have been interacted with the feminist organizations and met Minjung Art group.

It was the early year, which the term “Minjung Art” was not even existed. Kim In-soon came to the atelier that I shared with other friends and Kim Jin-sook was living in the same apartment of mine. The three women gathered like that in 1985 and did the group exhibition, October Group Show, which the title came from the Russian Revolution.

Then the second exhibition, From Half to One, in 1986, was the real feminist thing. It was like, “We are all female artists, we need to speak for ourselves,” and discussed to exhibit the works on the walls of the apartment buildings so that the housewives could easily access, which is unfortunately not actualized. At the time, each of us featured specific women’s issues: Kim In-soon expressed the working woman, I did the life of middle class housewife and Kim Jin-sook did the woman who is singing and doing Chang, Korean traditional narrative song. Through the exhibition, I met Alternative Culture2) and encountered the feminism as a theory, as well as began to study it. After a year, I met Feminist Artist Network.3) The organization exercised the feminist movement as a cultural act so that it fitted me very well. Fundamentally, painting is a solitary work but the feminism needs more than my single voice to exercise. So I agreed to support the organization and their act.

1,025: With or Without Person, 2008, acrylic on wood, variable size, installation view, Seoul Museum of Art, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

1,025: With or Without Person, 2008, acrylic on wood, variable size, installation view, Seoul Museum of Art, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

In the similar period, your name was listed on the women’s arts department of Minjok Art Association.4) Was there any difference of opinion between you as a feminist and the Minjung Art group?

I never had an argument with them. But the thing that I was personally disappointed was the part of the title, “department,” which implies that the women are “just one of them.” I was in the group and paid the membership fee for 10 years because it was one of few things for women at that time, but I was not a very active member. I stormed out from the oppressive housekeeping, then here I meet the sexual discrimination in a so called “progressive group.” Meanwhile, I could have space to breathe with Alternative Culture, and form a perfect “us” with Feminist Artist Network. Imagine how happy I was. I lively participated for about 10 years.

In 1990s, you started to make figures of women with discarded wood. In 2000s, Your interest on the female extended to the ecological subject, including abandoned animals.5) Can you describe the relationship between the two?

Through my early 10 years of oil painting on the flat surface, I felt stuck in the wall but I did not know how to get out. I could only move on to the installation and work with wood after I was heavily influenced by the group exhibition of South American artists at Bronx Museum, in US. It was the installation of wooden standing statues of 6 heroes, who impacted on the nation’s independence like Che Guevara, and it was almost like those figures were walking toward me. Another decisive moment after that was the visit to the birth place of Huh NanSulHun,6) in Gangneung, by myself. The house was very simple and I incidentally picked up a branch of persimmon tree on the ground. When I went back home, I tried to draw something on the branch. Because it was in a round shape, it became the round body of a human. Since then, I collected shabby wood and started to work with them. The leftover pieces from the timber yard are sometimes almost as long as 2 meters and 80 centimeters. I draw a painting on the part of it and cut the rest. As a material, the wood is soft and easy to manage, as well as has the splendid grain. After I wipe it clean, it is so lovely like the skin of human.

Humans are obliged to cut the wood and pick the leaves by their needs. However, I think there is a huge difference between feeling sorry for doing so and carelessly breaking another life form. I cannot say about the ecological ideology, but I think the essence of ecology is to respect the living things and have a sense of pity.

Above) Yun Suknam: Heart, exhibition view, Seoul Museum of Art, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun, theArtro

Above) Yun Suknam: Heart, exhibition view, Seoul Museum of Art, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun, theArtroBelow Left) 999-The Seeding of Lights (detail), 1997, acrylic on wood, 3x20cm, 999pieces, installation view, 2015, Right) Fish Market 2 (detail), 2003, mixed media, h:267, installation view, 2015 ⓒ Park Chang-hyun / theArtro

On this exhibition, you recalled the historic women figures including poets from the Joseon dynasty, Lee Mae Chang and Huh NanSulHun, and the wealthy merchant, Kim Manduk, who devoted all her fortune to save the people of Jeju island. Besides them, you have presented many female characters in the history. What is the meaning of restoration of women’s history to you?

I have been reading the critical biographies of the figures like Lee Mae Chang and Na Hye-sok, and I painfully empathize with them. It feels like I have lived their lives. Even though Huh NanSulHun was an aristocrat, she died at the age of 27. Huh was a great poet but born in a wrong time. I feel I must talk about those women, who had to live through the irrationalities. I am not sure why, but I am attracted to this subject and some images are keep coming to my mind. This exhibition is the third time that I featured Huh and Lee, and the first time for Kim Manduk, which I want to repeat through different approach and method. But what I truly wish to do is to pull out the life of unknown women. If someone was a female poet at that time, that means at least she was a gisaeng, Korean geisha, and she could make a some kind of living. But when I think about so many other unnamed women, who were married at 6 and died at 20 something, I sincerely wish I could relieve their deep sorrow. In one of the photographs I have, there are two little girls, who look like only 6 to 9, and they are milling with their bare feet and with their hair tied up. The hairdo means they are already married, which is almost as same as they are sold to this family. I am stifled and feel hurt with this. This photograph is from only about a hundred years ago, and I cannot imagine how it was before then. It must be better to be a gisaeng than being a wife of a family.

The feminist culture movement has started from your generation and was very active in 1990s and early 2000s. However, if we look at Korean society now, the heat has been perished. Can you tell us about the feminist art today? What do you see and pursuit?

The feminism act has been decreased, and it is not just for Korea. Except Arabic countries, the feminism seems to be gone into the academia, even in the West. The movement like gathering the strength and making the organization is hard to do nowadays. However, I can make the conclusion just for myself, which I will do my best to tell the stories of women through my works, and I am not sure I can cover all of them till I die. Because there are enormously many untold stories, I would keep on working, even if I am the last one.

1) After finishing the subject of maternity with the solo exhibition, The Eyes of Mother, in 1993, Yun started the Series from 1995, and projected the edgy life of housewife by placing the sofa with sticking out iron spikes in the pink room.

2) Alternative Culture is the organization for alternative feminist movement, which was founded in 1984. Cho Han Hye-jeong, cultural anthropologist, and the late Koh Jung-hee, poet, were involved in its establishment. The organization publishes many theoretical books of culture and feminism.

3) Yun was the director of the Feminist Artist Network for 10 years from 1997.

4) It is founded in November, in 1985, and played the leading roll of Korean Minjung Art movement.

5) In 2008, Yun presented 1,025: With or Without Person at ArKo Art Center. Yun read the article about Lee Ae-shin, who looked after 1,025 abandoned dogs and worked on making the sculptures and drawings of 1,025 dogs. It took over 5 years to finish this masterpiece.

6) Huh NanSulHun is a female poet in the mid-Joseon period. She already wrote a poem when she was 8 and had an exceptional talent on poetry. She died at her age of 27.

Kim, Sooyoung / TheArtro Editor