TheArtro introduces young Korean artists who have attracted international attention at Gwangju Biennale, Busan Biennale, and MediacitySeoul. At the 2016 Gwangju Biennale, artist siren eun young jung presented ‘Act of Effect,’ a work created as part of her ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project’ series, for which she has become well known. The title of the project refers to a form of traditional Korean musical drama performed by an all-female cast that has all but vanished since its heyday in the 1940s and ’50s. The artist brings the fading genre to life using such diverse forms as performance, video, photography, and installations and asserts a broader critical perspective on questions of gender and social norms.

-

- **siren eun young jung** siren eun young jung was born in Incheon in 1974. She currently lives and works in Seoul. She received her MFA and DFA in Fine Art at Ewha Womans University, Korea, and an additional MA in Feminist Theory and Practice in the Visual Art at University of Leeds, UK. Since her first solo exhibition at Brainfactory in 2006, she has held a total of five solo exhibitions and participated in numerous group exhibitions such as [“Discordant Harmony” (Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima, 2015)](http://www.goethe.de/ins/kr/seo/prj/har/enindex.htm), the [8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (QAGOMA, Brisbane, 2015)](http://eng.theartro.kr/arttalk/arttalk.asp?idx=52) and [Taipei Biennial 2016 (Taipei Fine Art Museum, 2016)](http://www.taipeibiennial.org/2016/). She is the Winner of [the 2013 Hermes Foundation Missulsang](http://en.fondationdentreprisehermes.org/Know-how-and-creativity/Exhibitions-by-the-Foundation/Hermes-Foundation-Missulsang-2013-at-the-Atelier-Hermes) (Art Prize).

“Humble as I am/ My heart is not humble/ Dirty as my clothes are/ My youth is not tainted”

An actress in dopo (the traditional garment worn by Joseon-era Confucian scholars) and gat (the traditional wide-brimmed hat worn by certain classes of men during the Joseon period), wearing dramatic, masculinizing makeup, walks onto the stage and performs a changgeuk (traditional Korean opera). Her complete transformation into a man, from the dressing room to the stage, and her singing of the plaintive tune—these sights, though utterly unfamiliar, evoke wistfulness in the one watching.

This is a scene in ‘Act of Effect,’ a work by Korean artist siren eun young jung and part of an ongoing project the artist began in 2008, ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project.’ Featured in the 2016 Gwangju Biennale, ‘Act of Effect’ provides a close-up look at the last generation of performers of an art form in decline, the traditional all-female Korean opera genre known as yeoseong gukgeuk. The film explores the quality of queerness, of being neither male nor female, and the emotions that surface in the spaces between the seen and the unseen. Jung’s earlier works ‘The Masquerading Moments’ (2009), ‘The Unexpected Response’ (2009), ‘Directing for Gender’ (2010), and ‘Off/Stage’ (2012) were all created as part of ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project.’

Another project the artist has worked on is ‘Landscape Project,’ which she began in 2001. Most of the earlier works in this series used personal confession as the means for communicating emotions and a message. But gradually the artist redirected her gaze to the social landscape: the high-altitude protest of laborer Kim Jin-sook, who stages a sit-in atop a 35-meter crane in the middle of the rainy season (‘Jangma’); a shantytown being torn down ahead of redevelopment (‘The Neighbour’); a man surrounded by wilting cherry blossoms proclaiming, “Believe in Jesus or go to hell” (‘In Full Blossom’). Beyond documenting facts, these works serve rather as a means of conveying certain emotions, presenting the most modern and realistic landscape.

In this interview, siren eun young jung was asked about the developments in her body of work and about her work at this year’s Gwangju Biennale. She shares her ideas on art and its possibilities.

siren eun young jung, ‘Le Nouveau Monde Amoureux’, 2014, Opening performance of the Mediacity Seoul 2014.

siren eun young jung, ‘Le Nouveau Monde Amoureux’, 2014, Opening performance of the Mediacity Seoul 2014.

You’ve worked on ‘Landscape Project’ since 2001. Early on, the works had the quality of personal confession, but I get the sense that there was a shift down the line toward more social, realistic concerns. Would you agree, and if so, could you talk about the reasons behind this?

You’re right. Personal confession ultimately takes on a social significance, becoming socially situated. I think personal confession ended up becoming a means by which I could enter into society and meet other people, outside of myself.

‘Dongducheon Project’(2007–2009) was the first time you focused on a specific group within society. What, if anything, did you find difficult about this project?

On the whole, it was difficult to engage with the female sex workers, to decide how to position myself in my interactions with them, what kind of conversations I would try to have, and whether it was the right thing to do to meet them at all. At every moment, there were ethical questions to confront.

Is there a reason you primarily use the media of video and performance?

During my time studying abroad, I began to avoid materials and forms that were heavy or bulky. I embraced the economical merits of video work, which could be stored in data form and wasn’t limited by the size of your working space. Today, I consider the kinetic, narrative, and temporal possibilities of video more important to my work. And then, while working on ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project,’ I met with people who had a strong sense of their identity as actors, so I began to think about the form of performance. I don’t think I even imagined before this that performance would one day become a primary medium in my work.

Left&Right) siren eun young jung, ‘Act of Affect’, 2013, Single channel video, 15min 36sec.

Left&Right) siren eun young jung, ‘Act of Affect’, 2013, Single channel video, 15min 36sec.

I heard that you got to see the all-female opera performance that became the material for ‘Act of Effect’ by chance. You said you deliberated about how you would establish relationships and at the same time maintain distance in ‘Dongducheon Project.’ How did you go about building your relationships with the actors in ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project’?

The actors I started meeting were mostly older women in their seventies, who didn’t seem particularly apprehensive about being approached by a young artist. At the same time, they did have the fear that their way of life would be looked down upon, or regarded with contempt, so I had my work cut out for me in figuring out how to relate to them. With ‘Dongducheon Project,’ my persistent concern was with maintaining distance and ethical position—engaging in solidarity with other people without “otherizing” them. With ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project,’ much more intimate relationships needed to be built, more like the relationship between a grandparent and granddaughter or between old friends than that of interviewer and interviewee, or writer and actor. It was important to frame the relationship in the right way at every moment.

How did the female actors respond to the shift from being performers on their own stage to performers in someone else’s work?

As might be expected, it was unfamiliar and somewhat awkward for them. The older actors, as the veterans they are, were capable of commanding the stage despite the unfamiliarity and awkwardness. The younger actors sometimes seemed anxious. But after the performances ended, the actors were usually relieved, and they also said it had been fun to experience something special.

In ‘Act of Effect,’ even after the actor’s performance has ended, the camera scans around the theater. During the performance, the camera similarly focuses on the mic stand or other minor objects. This flow seems like it could be the artist’s perspective or the performer’s perspective. Whose perspective are we seeing, and what were you thinking about regarding this aspect?

It’s the actor’s perspective, and it’s also actor’s spectral perspective, forever vanished. The female opera singers are women who have had to face the loss of the genre they have poured their passion into, the genre they love. I’ve thought long and hard about what this perspective looks like, the sorrow and mourning at all that is fading. I wanted to convey this as a kind of distress akin to that caused by conflict and sorrow, an affective state.

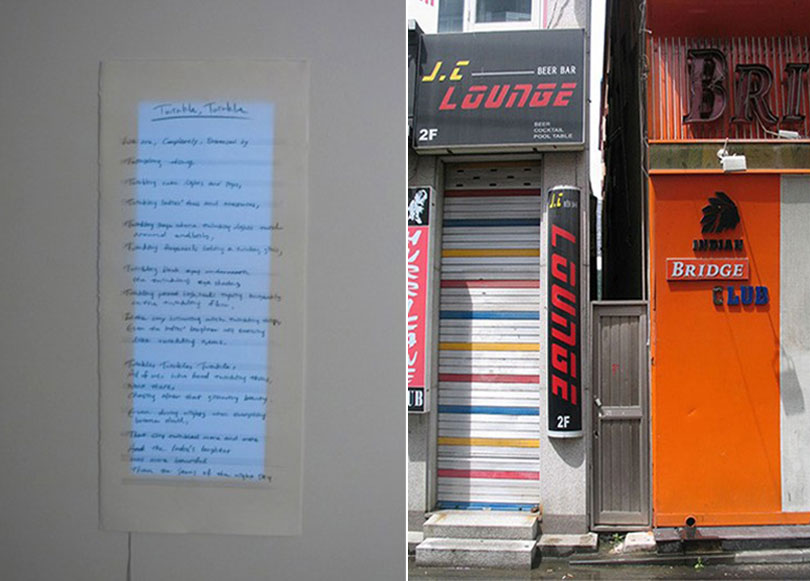

Left) siren eun young jung, ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’, 2008, drawing on paper, lighting.

Left) siren eun young jung, ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’, 2008, drawing on paper, lighting.

Right) siren eun young jung, ‘The Narrow Sorrow’ poster, 2007, 59.5×83.5cm each.

Has your approach to art changed over the course of ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project’?

Whereas before, the communication of a clear concept or message was more important, nowadays I focus more on the nuances, the emotional tone. I’m less interested, for example, in the concept of “the other” and more in the power of the emotions of the other, in the grieving of loss, and in the longing and suffering of life. I want to do art that encompasses these things.

In the politics of representation, through which things that were once hidden are revealed, how deeply can art become a part of society, and what kind of role is there for it to play?

Practically speaking, art doesn’t have much power; its intervention in society will always be inadequate. But I believe there is a different power, a kind that is only made possible in such insignificance and frailty. The power of art isn’t about changing society. Rather, art must create a different power, a different language, by which gradual fissures can be made in the norms that constitute society.

What are your plans for the future?

I will rewrite and rearrange ‘Anomalous Fantasy,’ which I presented for the first time at the Namsan Arts Center in October, and perform it at the Taipei Biennial in January and TPAM Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama in February. The title is the same, and the subject is largely similar, but the performances will have a different form and vantage point. From December 15 to February of next year, I will be an artist in residence at the Singapore NTU Centre for Contemporary Art. Also, I’ve been thinking about the best way to finish ‘Yeosung Gukgeuk Project.’ I’m planning to work on something a bit different beginning next year.