Anthropology of Images and Contemporary Art: Image and Death (4)

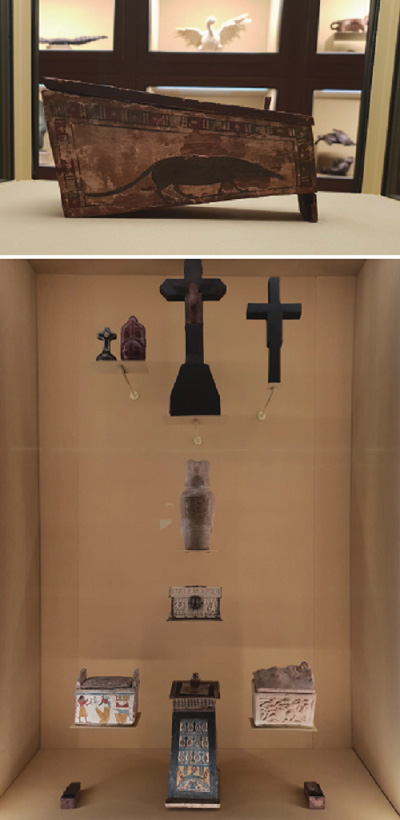

Exhibition view of 《Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures》, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Austria, 2018–2019. Photoⓒ Lee Nara

1. Inquiries

The First Inquiry: The Mummy in a Coffin

Beginning in 2012, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien(Vienna, Austria) has been offering curation opportunities to renowned creators in various fields, among whom Wes Anderson, a creator of perfectly coordinated images that illustrate fables of incomplete adults going through inner breakdown, and Juman Malouf, a designer who commands the fields of theater, film, and fashion, were invited as curators for the program’s third exhibition, 《Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures》(Nov. 6, 2018–Apr. 28, 2019). Anderson and Malouf created eight small “cabinets of curiosities” comprised of approximately 400 minerals, taxidermy animals, musical instruments, weapons, folklore objects, and paintings selected from some 4,000,000 pieces in the museum collection. Of these, 350 items have never been shown to the public since their acquisition (most likely considered short of exhibit-worthy by previous exhibition organizers). The exhibition put together by Anderson and Malouf almost seemed like a giant animation studio or a twenty-first century version of a Pop Art scene. If not, it looked like what could be considered a modern-day “cabinet of curiosities,” a pop-up shop carrying a selection of sophisticated design products. This exhibition completely set aside traditional museum-exhibition standards—assortment by chronological order, artists, nationalities, or medium—and before the audience was an event removed of history. The eight display cases in the exhibition hall forced viewers to take note of the craftsmanship of the mise-en-scène and the montage that placed the objects inside the cases rather than the objects themselves, much like Anderson’s use of tableau vivant in his films. In the dead center of the exhibition hall was the ancient Egyptian coffin containing a giant mummified spitzmaus(shrew), the star of the exhibition mentioned in the title. (Some more funeral-related objects were displayed in the room across from the coffin.) Why was this coffin, an object impossible to strip of symbolic meaning, placed in the center of the exhibition hall, purposefully bizarre and removed from almost all historical context, only to be characterized by its size, color, and gesture?

The Second Inquiry: The Shadow of Butadese

Gaius Plinius Secundus(Pliny), a Roman politician circa the first century, dedicates several paragraphs of Naturalis Historia (vol. 35) to introducing a myth on the origin of painting and sculpture. He challenges the Egyptians, who claim that they had invented painting approximately 6,000 years prior to his time, referencing the first ancient Greek clay modeler Butades who lived in Corinth. The story of Butades begins with his daughter Kora and her lover. Kora draws upon a wall an outline of the shadow of her lover before he sets off to fight in a war. Upon this outline, Butades models the face of her lover in clay and bakes it to turn it into ceramic. This well-known tale attests to the role of shadows in the birth of painting and sculpture. Shadows, much like mirror reflections, are images associated with physicality, whether humane or objective. Giorgio Vasari later wrote in Giotto di Bondone’s biography that he learned to paint pictures while drawing out the shadows of animals during his time as a shepherd. Instead of shadows, Leon Battista Alberti likened paintings to the reflections on the water surfaces into which Narcissus would stare. Did Pliny borrow these stories about shadows as grounds for belief that painting is ultimately an act of image-making craft seeking imitation of the original?

The Third Inquiry: Grisailles

Grisaille(originating from gris, meaning “grey” in French) is an art term referring to a painting executed entirely in shades of grey. Chiaroscuro, an Italian term originally referring to the technical use of contrast in color paintings, has also come to be used when referring to black and white or monotone works. Leonardo da Vinci praised the techniques of chiaroscuro and foreshortening as the epitome of painting. The audience today is likely to associate “monotone” with monochrome paintings by modern abstract artists, but the grisaille technique was widely used in glass works and paintings during the Late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance period. There are few structured studies on grisailles, but nevertheless, those who have studied grisailles prove that the technique was a method of expression used in figurative painting. The Paragone (the Italian Renaissance period debate over superiority of painting versus sculpture) is considered one of the main reasons for grisailles’ proliferation, for a grisaille enabled portrayal of everything that a sculpture can portray. For example, Andrea Mantegna, a northern Italian Early Renaissance painter known for meticulous brushwork, produced biblical grisailles reminiscent of relief sculptures. Flemish artists of the early Renaissance, who often painted biblical altarpieces in foldable series, added in statuesque grisailles of biblical figures on the outer panels—these particular paintings were imitative of stone sculptures but even more lifelike. At the same time, portraits of the commissioning patrons were never painted as grisailles; grisailles were reserved for the dead, the unearthly, or lifeless sculptures. Art historian Hans Belting emphasized in 『Miroir du monde』, in which he traces the origin of Flemish paintings, that the Flemish altarpieces revealed life and color only when the outer panels decorated with figurative grisailles were opened to reveal the inner panels. (Altarpieces made of multiple panels showed the church audience the outer images when closed and the inner images when opened.) Aby Warburg, who suffered a severe mental illness towards the end of his life, left fragmented and therefore somewhat incomprehensible notes regarding grisailles, saying that in Renaissance paintings, the grisailles are vestiges remaining of ancient images and the point of energy balance. At any rate, Warburg must have thought that it wasn’t enough to see grisailles as mere attempts to prove painting superior to sculpture. What more, then, do grisailles let us see?

2. The Anthropology of Images of Shadow

Let’s first address the second question about the shadow in the story of Butades. Art historian Victor Stoichita, who wrote 『A Short History of the Shadow』, infers several issues not elucidated by Pliny in his reference to the anecdote of Butades. What Kora experiences in the story is more than just disappearance of an erotic subject that once physically existed before her. Her lover, soon after his departure, would have died a heroic death on the battlefield. The shadow in this case has to be seen not just as an image resembling physical qualities, but as an image representative of ancient anthropological imagination surrounding human fate and shadow.

In 『Pour une anthropologie des images』, Hans Belting stresses how Western civilization, in light of the anthropological event of death, has endowed the image of shadow with great importance. Belting examined not only the images conjured in the minds of those with a body such as dreams and mental pictures, but also the history of images that serve as simulacra of the human body such as portraits, figure sculptures, and masks. We, who have bodies, die. Death is a crisis, an event experienced by and limited to our bodies, and it’s also where the relationship between shadows and image fabrication begins. If we weren’t to die or disappear, if our bodies weren’t to rot, we may have found the shadows of our bodies less significant. From Homer to Virgil, the existential status and function of the shadow in ancient Greek and Roman cultures are as important as the status and function the “soul” holds in Western Christianity, which sought to overthrow the former. Based on the ideas that dominated the ancient cultures, Dante Alighieri, a Late Medieval poet, imagined Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven beyond the mortal world. 『The Divine Comedy』 introduces stories of the dead who live as shadows in a world on the other side of life. Dante, an undead protagonist who travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven in the story, meets the dead, one of whom is the ancient Roman poet Virgil, and sees that they’re still retaining their lifetime appearances. This explains that Dante imagined the dead as beings of shadow-images—unlike the living, these beings don’t have a body, but an external appearance similar to their lifetime bodies. These impalpable, translucent beings have bodies of shadow which shed no shadow of their own. As can be seen in Dante’s depiction of the dead, humans, aware of their mortality, have been invested in the concepts of shadow and soul as a realm separable to objectivity and physicality, able to imagine the “life of the dead” via the two concepts.

(Left) Jan van Eyck, 〈The Ghent Altarpiece〉, open view, 350×461cm, c. 1430–1432. (Right) Jan van Eyck, 〈The Ghent Altarpiece〉, closed view, 350×223cm, 1432.

(In 1465, when celebration of the 200th anniversary of Dante’s birth was at its height, there appeared in front of his tomb in Ravenna, Italy, a giant mural depicting his Divine Comedy. In the lower left of this mural are figures descending to Hell, and in the background are figures climbing up the spiral hill of Purgatory leading to Heaven, figures who seem to be maintaining the appearance of live bodies even after death. According to the Catholic Church, the human soul does not carry bodily memories—the body rots underground after death and only the soul may be saved. Those who believed in the Catholic teachings also saw the mural, portraying the dead as translucent bodies, shadow-bodies, virtual bodies reminiscent of actual bodies but bodies nonetheless.) If not through the Christian mode of “souls,” we the living imagine the dead who remain in our world in forms such as “vindictive spirits” or “ghosts.” Beyond an image resembling of an object or body, the shadow—as a concept associated with objects or bodies but not the same as either—is an anthropological contrivance onto which the living, revolving around the existential event that is death, project their shared fear and hope as a mortal kind.

In the beginning of 『A Short History of the Shadow』, Stoichita follows through variations of Butades’ story succeeded down by Quintilianus and Athenagoras to draw a similar conclusion. The image Kora created to resemble the departee should serve not only to remind her of his face, but also as an emblem of well-wishing, as the original model is destined for danger. Furthermore, Butades’ addition of clay and fire can be deduced as an act to follow the heroic death of the original model, in which case what Butades has created isn’t a simple object but a second ceramic body indwelled by the soul of the dead. Stoichita speculates that the ceramic piece later became an object of worship in Corinth. In this regard, Pliny’s take on the story tells us that the act of painting or sculpting began as an act of creating an image imitating a shadow—a blurry outline of a human body—that is, the act of imitating the image of an image. It also emphasizes that the image made first from the outlined contours, then out of clay, is something symbolic that replaces the body of the dead or the absent, therefore, an image of hope. If so, what Pliny sought to define as the original impetus of painting and sculpture in light of this story isn’t completely remote from mummification (the symbolic modeling of a second body) practiced by the Egyptians in attempt to preserve the body beyond death. Stoichita adds that in ancient Egypt, the ka, the soul of the dead imbued in the Egyptian sculptures, was also envisaged as a light shadow, as opposed to the khaïbit, the shadow of the living, which was envisaged as a dark shadow.

Domenico di Michelino, 〈La Divina Commedia di Dante〉, 1465.

3. In Search of the Lost Mummy

As widely known, ancient Egyptians produced mummies so that the soul of the dead could reunite with its body and continue to live in the afterlife. Hans Belting once described mummies as “corpses that became images.” A mummy, once it’s become an image of an indestructible body, is able to speak to the soul of the dead. This is why the ritual of the opening of the mouth, the last part of the time-consuming mummification process, was performed with grave importance by ancient Egyptians. Going back to the spitzmaus mummy in the coffin, there in the exhibition space of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien were all sorts of boxes imaginable, such as the coffin and other boxes containing organs. These objects, placed alongside a series of taxidermy animals, raise a question: should this exhibition be seen as a large vessel containing organs necessary for mammals to live? But then again, there’s also the empty vitrine once used at an art and industrial goods exhibit held in 1890 in Vienna. The Egyptians thought of the corpse as a vessel, a vessel cardinally purported to re-embody the soul symbolized as the shadow. We could ask, then, do the coffins, boxes, and vessels referencing the ancient Egyptian funeral rituals in this exhibition hypothetically carry something invisible—a soul of sorts? Or do they exist on their own as means to prove that, in the real world, what remains is only the formality itself? Walking with these questions in mind towards the very edge of the exhibition space past the spitzmaus mummy coffin in the center, there’s a 16th century portrait of an eyes-closed deceased. The images of death prowling through the exhibition space makes us defer the cynicism that sees the coffins as mere empty boxes.

Portraits, realistic ones in particular, replace the “corpses that became images.” At a time when the common belief sanctioned the existence of a world beyond that of current life, Dante, as aforementioned, used his poetic imagination to travel beyond to Hell and Heaven. However, average people were bounded inside the earthly world until they experienced death for themselves, only conjecturing what’s beyond through images of the body: the images of the body in ancient Egyptian funeral customs, the ancient Roman imagos modeled after the face of the deceased and kept in homes, the anthropomorphic depiction of the Christian God—the humanly yet non-human being who died for human sins. Stoichita and Belting examined the Late Medieval and Renaissance period biblical paintings portraying events such as Jesus’s resurrection, miracles performed by saints, and the last judgement—events inexplicable through reason—and noticed a change in the way the shadows were being handled. Using Masaccio’s 〈The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden〉 as an example, Belting pertinently points out that the shadows of Adam and Eve in the painting imply that the painting is a “fictitious perception of the world.” The shadow here no longer discusses the issues of life and death, but human existence on earth and their inner qualities. As humanity began to see death as a scientifically explicable event, shadows began to be portrayed as an “empirical” phenomenon caused by the relationship between light and objects. And the dead began to be depicted as skeletons and corpses, in other words, as evident remains in this world. Also around this time, realistic portraits of contemporaries began to be painted. These portraits would become an image of reminiscence that replace the absent when they’re gone. Humanity soon began envisioning the physical world as the only world they’re capable of residing in and began replacing the images of cadavers with images of the opposite—the living or the living moments of the once lived. Realistic portraits and fictions in images emblematize our pertinence to the world of physical law. And for this reason, some argue that the regressive pursuit of an alternate world, a world of death obliterated of life, only causes an overflow of images dissimilar to our bodies. Wes Anderson’s films, seemingly overly-faithful to the mechanical movements of the impassive characters and superficial aesthetics, have in fact never ensconced his admiration for the childish world, the animal world, the incomprehensible world of secrets. Anderson, well-aware of the contemporary times and its inclination towards boxes instead of mummies, placed in the entrance of the exhibition a portrait of a hirsute family whose faces are covered with fur, which tells us that through these dissimilar body images and peculiar objects, Anderson just may be fantasizing, if only for a moment, about a world beyond our own.

(Top) Ancient Egyptian coffin containing a giant mummified shrew at the center of the exhibition hall. Photoⓒ Lee Nara, (Bottom) Exhibition view of 《Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures》, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, 2018–2019. Photoⓒ Lee Nara

4. The Temporality of Grey

In a time when films are predominated by digital images, Wes Anderson produced two feature films in stop-motion animation, capturing real-life figurines frame by frame to configure movement. The human, fox, and dog characters appearing in the two films are immobile and lifeless in real life, yet in the film, they are vital and active. Just like the Egyptian mummies, these figurines are, in every way, images that serve as a form of carrier or medium. Film critic André Bazin once referred to the images on film in general as “mummification of objects.” An art of light and shadow is, in other words, an art of movement and arrest, and hence an art of oblivion and memory. I asked, in the beginning of this piece, why grisailles are vestiges of ancient memories. Before delving deeper into this matter, though, let’s take a somewhat long detour to the territories of moving image, mummification, and the translucent shadow that is film.

Novelist, traveler, documentary filmmaker, and installation artist Chris Marker narrates in his documentary essay "Sans Soleil"(1983): “I remember that month of January in Tokyo, or rather I remember the images I filmed of the month of January in Tokyo. They have substituted themselves for my memory. They are my memory. I wonder how people remember things who don’t film, don’t photograph, don’t tape. How has mankind managed to remember? I know: it wrote the Bible. The new Bible will be an eternal magnetic tape of a time that will have to reread itself constantly just to know it existed.”

Marker was insistent not to leave any objective or official record of a time, the times, or history. Marker’s films, often described as “poetic films” or “essay films,” address political situations experienced by communities of certain times, yet use voiceovers to deliver opinions and sentiments. The act of making work of art is in line with the act of recording and remembering a time, the times, and history. And history written in such forms is in contrast with the official and monumental history. Such records of time not only resist authoritative oblivion and oblivion in general, but they also force us to re-recognize our shudderingly unintentional oblivion. The above-cited film narration treats internal memory like a record of audiovisual images imprinted by the camera, i.e. equivalent to a memory existing outside of the human body. But are these extrinsic memories inscribed on film more objective and uncontaminated because they are placed outside our bodies? Upon “the image,” we recall or forecast the unavoidable and eternal human oblivion and its cause—the encroaching death. Records like Marker’s are records of things that once existed, and at the same time, they are records demanding oblivion and remembrance. This is because Marker’s images and voiceovers force us remember by bringing the past into present, but also preannounce our future oblivion of the recovered past. The ambivalent hence grey temporality of the images that are lost to be recovered, born to be dead, would be the reason Marker compares film (or video cassettes, the popular carrier medium of image memories at the time) to the Bible.

Georges Didi-Huberman recognizes this ambivalent temporality in the Renaissance period grisailles, Alberto Giacometti’s portraits, Gerhard Richter’s paintings, and other cotemporary grey monochromes. He asserts that the translucent grisaille figures painted on the outer or corner panels of the Late Medieval and Renaissance altarpieces aren’t just painterly means of flaunting sculptural techniques; that they embody biblical interpretations of their subjects. The greys in the grisailles were painted in pigments neither immutable nor abstemious; Rather, the pigments were damageable and vulnerable. And the grisailles of Mantegna, revered for faithful imitation of ancient stonework, as featured in Panel 49 of Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne, are in fact much like “elegant ghosts emerged out of old coffins.” The more vivid the traces of the ancient times, the more emphatically they point to the imminent future disintegration of memory. Owing to the ghostly shades, grisailles were able to meticulously physicalize the solidity of the stone and its crumbling, the air, and even breath. In this sense, grey, the color of sarcophaguses and ashes, can ironically be used to manifest vitality—Warburg’s mention of the “balance point of energy” could be referring to this very point.

While sketching out seemingly disparate exhibitions, stories, and techniques, this series, observing works, exhibitions, and histories surrounding the relationship between images of death and anthropological questions, ultimately aimed to call into question the paradoxes of life and death, of body and image, and of memory and oblivion. People of the present day no longer make mummies; we record and remember. Yet simultaneously, the time recorded on film is a time as forgotten as the time written in stone. What would film be if not the bandage wrapped around the mummy or the mummy itself? The more we’re governed by the laws of physics, the more we will search for bodiless shadow-images that counter the laws. And some of the works of our time will be the symptoms of such inquisition.

※ This article was published in the February, 2019 release of Misulsegye Magazine as part of the Visual Arts Critic-Media Matching Support Project by the Korea Arts Management Service.

Lee Nara

Image Culture Researcher