The cover of the May 2019 issue of [Misulsegye] is Yong Meon Kang (b. 1957), an artist dedicated to translating tradition into modern forms of sculpture. His twenty-second solo exhibition 《Tradition Incubate》 (Apr. 1–Aug. 31, 2019) is currently taking place at the Awon Museum in Wanju, Jeollabuk-do, where his works create an exquisite harmony with the reconstructed hanok venue to offer audiences an extraordinary experience. This article presents an overview of Kang’s course of work from the 1980s woodcarving works that won him recognition in the scene to his most representative piece, 〈Dizziness〉 (2014), as well as the eponymous series shown at his Seoul exhibition 《Solidification》 (Gonggansail, Aug. 29–Sep. 9, 2018).

Kang majored in fine art at Kunsan National University and earned a master’s degree in art education from Hongik University. Beginning in 1991 at Eol Gallery in Jeonju, he’s held 22 solo exhibitions and has participated in group shows such as the Sea Art Festival at the Busan Biennale, presenting works around the country in venues like the MMCA, SeMA, Jeonbuk Museum of Art, Daejeon Museum of Art, and the Gyeonggi Provincial Museum. He is currently the head of Ariul Visual Arts Institute and is also serving as a cultural diplomacy advisor for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His awards include the Special Award of the Grand Art Exhibition of Korea (1990), the Excellence Award from the JoongAng Fine Arts Prize, the Jeonbuk Young Artists Award (1991), the Grand Prize from 《The Korea Times Young Artists Invitation Exhibition》, and The Face of Glory in the cultural arts category of The Proud Jeonbuk People Awards (1995). His works are owned by the MMCA, SeMA, and Jeonbuk Museum of Art.

Exhibition view of 《Tradition Incubate》. On the left is 〈April Tears〉, and to its right is 〈Dizziness〉.

Painted wood sculptures penetrate into the realm of modern art

It’s interesting that a retrospective of Yong Meon Kang’s artistic world should be held at Awon, a 250-year old hanok residence transported and reconstructed into a cultural space in Oseong at the foot of Jongnam Mountain, because if there is one theme that runs throughout the diverse works he produced over the past 30-some years, it’s “tradition.” His works, not only exhibited in the gallery space but also around the outdoor areas of the estate, create harmony with the steep slopes of the mountain and the curves of the hanok roofs to present themselves in new light and context. Using the works shown in this exhibition as a guide, let’s begin to look into the artist and his career.

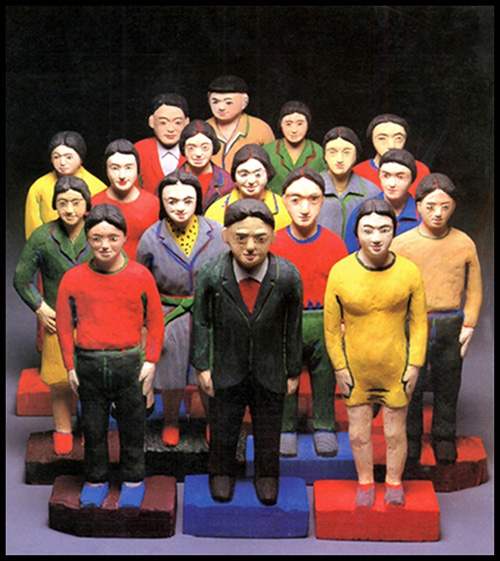

〈The First Year of History〉, a wood sculpture series featured in this exhibition, can be seen as the root of all the diverse works by Kang. The painted figures, carved somewhat crudely out of wood, conjure a sense of compassion. This bicolor wood sculpture series decorated the first steps of his career quite ornately. While experimentation with color in sculpture is nothing new—even an old tradition in both the East and the West—painting a finished sculpture in Korea, especially in the 1980s when a new foundation for art education was in establishment, was seen as “spoiling a perfectly finished work for nothing,” or as derailing from the unspoken rule or standard. 〈The First Year of History〉, produced in the late 1980s in attempt to recreate the aesthetics of Korean traditional marionettes, was shown in his solo exhibitions in 1991 and 1992, imprinting Kang’s name in the art scene and breaking the prejudice against painted sculptures.

Yong Meon Kang, 〈Taking a Lesson from the Past – Maninbo〉, 2004. paint on wood, 5×5cm each.

In “Contemporary Transformation of Humble Folk Aesthetics,” a critique on the exhibition 《Yong Meong Kang Sculpture Exhibition: The First Year of History》 (Nov. 25–Dec. 4, 1994) held at Kumho Museum of Art, critic Wankyung Sung praised Kang’s wood sculpture style corroborated through three solo exhibitions, saying that his works are “rooted in Korean tradition, [. . .] friendly and familiar, yet surprising.” Favorable reviews poured out throughout the 1990s. Not only was Kang selected as a Prominent Young Artist by the [Wolganmisool] magazine, but he also won a series of awards including the Special Award by the Korean Fine Arts Association (1990), the Excellence Award from the JoongAng Fine Arts Prize, and the Grand Prize from 《The Korea Times Young Artists Invitation Exhibition》, and was even introduced on a German TV program during the 《‘98 Korean Art Tour Exhibition in Germany》 held in Berlin and Aachen. To Kang, who had been exploring Korean traditional aesthetics, this must have given him some assurance that there is desire for this kind of aesthetic out there in the world.

Yong Meon Kang, 〈The First Year of History〉, 1997. paint on wood, 9×17x45cm each.

Contemporizing tradition

In 2000, when Kang introduced more abstract and patternized wood sculptures at 《Taking a Lesson from the Past: Yong Meon Kang Sculpture Exhibition》, artist Dusu Choi wrote in the foreword of the exhibition introduction that "Kang is chasing two rabbits: our tradition, which has been severed from us, and our contemporary lifestyle, which constantly forces us to change.” The last paragraph of this text is all the more noteworthy: “The issue of tradition versus newness is taken very seriously by Kang’s generation. This is the generation who experienced firsthand the vulgarity of Korean history, the overbearing impact of tradition on the modern history of South Korea. These are the people who lived through the 20th century with a 19th-century mentality, who welcomed the 21st century in fear.” Reduction of this particular sentiment towards tradition down to the traits of a generation risks discounting of details, but in reality, the issue of tradition has oftentimes been a major topic for the artists born in the 1950s–1960s. Kang also said in an interview with [Misulsegye] on April 8, 2019, that he believes “preserving Korean art with pride and evaluating it based on our own ways of thinking is how culture diversifies and human lives become rich,” confessing that the idea of “Koreanness” is still in the heart of his work. After all, the title of his current exhibition is 《Tradition Incubate》.

Though the meaning has faded after so much exploitation, “contemporization of tradition” is an idea that power-handles people who experienced a rash disconnection from their own heritage and culture. Korean people, who struggled to catch up to the Western living standards from the ruins of the Japanese colonial rule and the Korean War, are a quintessential example. So, what exactly do we mean when we say “Koreanness,” or “Korean aesthetics?” In a broad sense, it would refer to the traditional art style from the Joseon period or earlier, but the term doesn’t seem to address merely the visual appearance or technique of Korean art. What Kang and his generation refer to when they say “Koreanness” is more of its “spiritual” aspect.

Exhibition view of 《Tradition Incubate》. 〈The First Year of History〉 is installed in front of 〈Dizziness〉.

So then, let’s delve into the meaning of Kang’s sense of “Koreanness” in more detail. He clearly denotes in his works influences of shamanism and the Confucian culture experienced in his youth. The tradition of studying Chinese classics has continued as a form of social discipline, so in a narrower sense, Kang, who was born and raised in Gimje, Jeollabuk-do, and still works in Gunsan, Jeollabuk-do, which is a region widely rooted in the shaman culture, can be seen as sublimating the regional culture into his works. But in a broader sense, the “Koreanness” he seeks to express in his works isn’t just traditional custom itself, but the impetus behind it, that is, the “root of the root.” This fundamental spirit, preserved and materialized in the form of various cultures and customs, was something the artist grew up with and still lives with, but simultaneously, it’s something that’s becoming more and more obsolete, buried by the sudden national division and rapid sociocultural development, which is why the search and succession of tradition can be seen as something equivalent to modern-day archaeology. Without people like Kang, chunks of tradition will soon be lost and forgotten. And it must have been for the sake of this archaeological calling that he never left his home region and stayed immersed in his work.

Works like Kang’s, the basis of which is an understanding of both the formality and the concept of tradition, help appropriate meaning and value to the many traditions that remain either as concepts without formalities, or as formalities without justifiable reasons. How meaningful is it that his first major series 〈The First Year of History〉, inspired by the marionettes used to decorate funeral biers, forced the art world to rediscover the beauty of painted wood sculptures?

Yong Meon Kang, 〈Taking a Lesson from the Past – The Spiral〉, 2009. paint on wood, 80×80×220cm.

Variation and expansion

With all that said, however, the beholder should soon realize that there are more ways to look at Kang’s works than from the “succession of tradition” point of view because the diversification and evolution in the works come across as more eminent than their traditional aspects. Though he had earned recognition for his painted wood sculptures, he refused to settle there. The reason was simple: “An artist has to keep up with the times.” By “keeping up,” he doesn’t necessarily mean “staying ahead” in the art scene, but “staying attuned” to the society that surrounds it.

In the 1980s for example, when Kang’s early works such as 〈The First Year of History〉 showed traditional aspects in a more direct manner, reclamation of “Koreanness” discarded and erased by the rapid industrialization was considered a social obligation regardless of progressive or conservative political orientation. And empathetic to the cause, Kang sought to interpret formal aspects of the funeral tradition he grew up with into contemporary art. Nevertheless, as such work continued on for over a decade, it became clear that there were limitations to finding new identities through the old, and Kang’s works underwent a series of transformations thereafter to reflect a story more relevant to the contemporary times. The reason the periodical shifts in his work feel so drastic is because most of his works boast a scale larger than the artist himself; the bigger the artwork, the bigger the amplitude felt standing before it. The wood sculptures, which are clearly extensions of his earlier works, have also evolved into many varied forms: from the original marionette sculptures, some evolved into pattern reliefs, some were amalgamated into large masses, and some were suspended in air. But the most radical and recognizable shift was in the works produced after the turn of the century, which abandoned the medium of wood entirely. Works like 〈Taking a Lesson from the Past – Buddha〉 featured in his 2004 exhibition were composed of acrylic tile pieces on brass wire framework, depicting traditional icons such as Buddha, roof tile designs, and roosters but proposing a whole new aesthetic.

Yong Meon Kang, 〈Taking a Lesson from the Past – Buddha〉, 2004. mosaic on brass wire, 80×60×100cm.

The series of four solo exhibitions from 2006 to 2008 were held under the same title, 《Taking a Lesson from the Past》, with “Light,” “Tree,” “Humility,” and “Empty” as the subtitles. Exhibition manager Seong-eon Ham recalls that, among these exhibitions, “《Taking a Lesson from the Past – Tree》 particularly showed works far removed from what the critics and the audience had envisioned Kang’s works to be,” going into detailed descriptions of the materials—the electric kiln, the automobile paint machine, and acrylics—and the production techniques. The transformation was astonishing, enough to make the viewers predict that his next work would fall in line with the thesis-antithesis-synthesis principle through which tradition is transformation to reconcile with the contemporary. The current exhibition at the Awon Museum features none of his acrylic works, but the use of synthetic resin, urethane, and LEDs in his later works attest to the progressive shifts in his work as well as the ongoing expansion of this scope.

Most of the works featured in 《Tradition Incubate》 were already shown in his earlier exhibition 《Solidification》-eye-catching works with massive volume and rugged textures. But this time, these resin and urethane sculptures, overlaid with thick layers of oil paint for texture, are installed outdoors among the hanoks and the surrounding nature. Whereas these works had exaggerated presence indoors, they blend into the nature outdoors. This exhibition differs from 《Solidification》 or other previous outdoor installation projects in that it presents the works in the context of the nature and the hanoks. And what enables the sculptures to retain their voices despite the shift in the medium is the consistency or the artist’s insistence on using the highly saturated “five cardinal colors.”

As can be seen by the selection of Kang’s representative works in this exhibition, the artist has broadened the scope of his work by leaping from his existing works rather than abandoning them to begin anew. And thus his artistic world has become an expansive territory embracing various characteristics. His rice bowl (a mounded bowl of rice often offered in ancestral rites) piece, exploring the subject of our daily ritual for example, has been reproduced in various materials and forms. This exhibition introduces one with a heightened presence of the matière, but there have been other variations made of stainless steel and flowers. And such bold variations are only possible because there’s the encompassing theme of “contemporization of tradition” underlying in each of the works.

Yong Meon Kang, 〈Anxiety〉(partial image), 2004. resin, ink, panel, 180×360cm.

Yong Meon Kang’s Anthropology

The 〈Dizziness〉 series which began in 2004, a little earlier than the 〈Solidification〉 series, can be seen as the most emblematic among his recent works. This ongoing series is directly in line with 〈The First Year of History〉 series in that it involves wood figures. Inspired by Ko Un’s poem “Maninbo (Ten Thousand Lives),” Kang began to carve out faces: faces of the figures described in the poem, of the people around him, and of contemporary figures spotlighted by the media. Over the course of fifteen years, the work continued to evolve, although they remained part of his existing series under titles such as 〈Taking a Lesson from the Past – Face〉 and 〈Taking a Lesson from the Past – Maninbo〉, and the faces in the works also retained the same color scheme, which was why they were understood in the context of his previous works.

It was through his 2014 exhibition that the 〈Dizziness〉 series began to possess an impact of its own as an independent series. The biggest change was that the different colors that had characterized the figures were now replaced with black. Through the use of monochrome, the works, which used to draw attention to the individual figures, began to be perceived as a massive whole. Each figure, darker and more serious than when it was colorful, seemed to be enduring a certain weight of reality. In “A Unified Community Sprouting from the Land of the Republic,” critic Sang Yong Shim referred to this sense of weight as “narrational tension,” addressing the individual figures as “the people” while reading out their democratic solidarity from the piece as a whole.

It’s the process of congregating small elements to create a large piece, the harmony of the different stories told by each figure, that adds power to such interpretation. The individual character carved into each small figure makes it seem like they have personal stories to tell. The artist says that he was only able to make one figure a day in order to fully capture both the external appearance and the inner qualities of the real-life models. Some faces may be technically easier to carve than others, but 〈Dizziness〉 is a labor-intensive work comprising hundreds, even thousands of faces, which is why it becomes such a spectacle and leaves such a powerful resonance. Arts Council Korea named this exhibition as “outstanding” and even organized a tour of the show in four regions around the country. Woojin Culture Foundation invited Kang Yong Meon for their 25th anniversary exhibition in 2015, the title of which was 《One is a human and a world only when one is placed among humans》 (Mar. 19–Apr. 8, 2015). This exhibition showed the epitome of gathering smaller elements to create a large-scale piece, conjoining not only faces but all sorts of small black elements including full-body figures and hanoks.

But then why did Kang name the piece, a congregation of figures, 〈Dizziness〉? His answer was that the work represents the relationship between human beings, which naturally includes conflicts. Unlike the past when we were limited to meeting a certain number of people around us, in today’s complex society, we encounter countless people through different channels and form intricate relationships, which made the artist feel “dizzy.” Even if the figures in the work are in an equal and “democratic” relationship as interpreted by Shim, a perfect democratic society would be all the dizzier, for the more equal a society is, the more it would have to rely on individual and relative standards instead of forced or standardized rules. In this sense, we are headed the right way, though it may be a lot dizzier than the easy way.

Yong Meon Kang, 〈Solidification〉, 2018. stainless steel, steel frame, epoxy, oil paint, 150×150×210cm.

If 〈Dizziness〉 is a metaphor for contemporary society, 〈April Tears〉 installed next to it addresses a social issue in a more literal way. Kang, who visited Paengmokhang Port upon the Sewol ferry disaster, only managed to express his pent-up emotions four years later through a sculpture shaped like a melting lump of sadness. 〈Solidification〉, which looks similar but simpler in shape, also expresses emotional build-up or congestion. It’s interesting that these two works should be installed in the indoor gallery space of the Awon Museum and on the water surface of the outdoor infinity pond, respectively. Perhaps the artist thought that an emotion so intense and grave could only be fully fathomed through comprehensive observation, including its mirrored reflection, or maybe he wanted to say that our feelings are like the sculpture, floating on the water of unknown depth. It seems Yong Meon Kang’s works, which began from tradition, have worked their way deep into the “root of the root” to finally reach the most intimate corner of human psychology.

Ten years ago, after seeing Kang’s 2009 exhibition, critic Eunyoung Cho proposed “finding the exquisite balance between localization and globalization” as his immediate objective. Then let’s assess where he stands in terms of this objective by assessing the array of works in his current exhibition. His interest in the contemporary people seems to be in line with the underlying theme, so is the regional aspect of his works still prominent? It sure is, because as noted above, the initial methodology of painting wood sculptures is continued in the present. The problem lies in the sense of old-fashionedness conjured as a result of the clash between the traditional and contemporary—the touches that felt sophisticated added to the original medium feel awkward in conjunction with the new materials. How he refines these edges will determine the degree of visual completeness in his works. When [Misulsegye] recently visited his studio, new styles of works that have never been shown before were in production. Perhaps these works will offer a sensation different from his works so far, but regardless, his exploration of tradition and humanity (strictly speaking, the two are one and the same) will continue, and his artistic world will continue to expand. And the broadened scope will enable him to select and compile better works as seen at the Awon Museum exhibition, which leaves us feeling anticipation rather than concern.

※ This content was first published in the May, 2019 release of Misulsegye Magazine and has been re-published on TheARTRO.kr after a negotiation was reached between Korea Arts Management Service and Misulsegye Magazine.

Jihong Baek

Jihong Baek, majored in Arts and Aesthetics, worked in the monthly art magazine Misulsegye as a journalist from 2013 and as editor-in-chief from 2016. With his interest in the distribution and consumption of art as much as in the creation of art and culture, he endeavors in curating and critiquing encompassing from the fine art to the popular culture.