Listen to the City, active since 2009, is a creative collective encompassing art, design, architecture, and urban advocacy. Listening to stories of how those at the margins of society have been victimized by various practices and events, the group raises awareness of social issues, leads different forms of activism, and explores sustainable methods of development.

At sunset, the sky begins to reveal all that has been hidden by the blinding light of day: dust escaping from a forgotten crack, gaps in the wallpaper, the bleak corners and hidden colors of buildings. All these and more appear when the sun melts into the horizon. Like the setting sun, Listen to the City sees into the hidden spaces and hears the real stories of those who have been overlooked in the light of day. Although these stories are all around us, they have been rendered invisible by the glaring light. Listening to these stories, Listen to the City seeks ways to return “the public to the people.” To do so, they must “produce a language” to represent this goal and create “the space of the issue.”

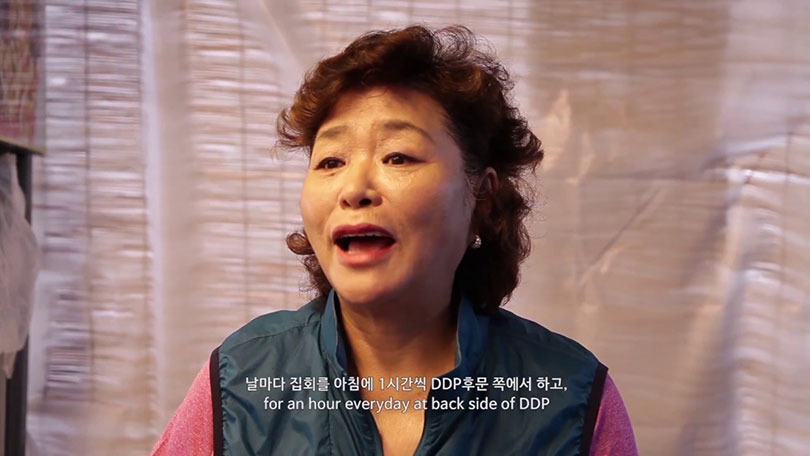

Listen to the City, 〈Cheonggyecheon, Dongdaemun Gentrification〉, 2017.

The City That Lost Its Memory

Korea is known as the country of rapid change, and no part of the country changes more rapidly than Seoul. The city is changing every second, but one thing that never changes is the loss incurred by such change. According to the inviolable laws of change driven by capitalist desires, whatever had previously existed must disappear. As the cityscape is continuously torn down and replaced by increasingly sterilized versions of itself, we are urged to look only forward, never back. As such, there is no attempt to remember what once was, no narration to remind us of what once occupied the space. Who can turn back the flow of time that had accumulated in the space? As seen in the neighborhoods of Hongdae, Cheonggyecheon, and Dongdaemun, such changes are characteristic of urban space. But in Seoul, the changes have become so rampant that it is now difficult to define the essence of the city.

While the Seoul cityscape has always been subject to change, the topography of the city was particularly transformed over a ten-year period by the sweeping policies implemented by two former mayors, Lee Myung-bak (2002-2006) and Oh Se-hoon (2006-2011). Two of the most significant projects overseen by these two mayors were the uncovering of Cheonggyecheon stream and the construction of Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP) under the “Design Seoul” campaign. Like a massive pair of scissors, these development projects chopped away the history and ambience from the heart of the city. While the projects have yielded some positive surface results, the deeper wounds suffered by the people who had been living and working in these areas have not yet been diagnosed, let alone healed.

Observing the sad results of this “progress,” Listen to the City responded with their book 『The Hidden History and Star Architect of Dongdaemun Design Park』. They wrote, “At the time, Mayor Oh Se-hoon was the embodiment of power, so no one criticized the DDP project. In fact, our book was the only one that took a critical perspective. It felt like South Korea was living under a dictatorship. But we believed that the city is not composed solely of those with money, but also those who are not invited to participate in governance. That’s why we launched the anti-gentrification movement.”

In accordance with the group’s name, Listen to the City actively listens to the stories of the city by achieving solidarity and communicating with people who lack a social voice. For 〈Cheonggyecheon, Dongdaemun Gentrification〉 (2017), they interviewed many people who once owned shops and businesses around Cheonggyecheon and Dongdaemun Stadium, who describe how they were forcibly relocated from the area starting around 2007. In the interviews, the small business owners explain that, just as they were finally getting settled and starting to enjoy better business, they were forced to move from Cheonggyecheon to Seoul Folk Flea Market in Sungin-dong. Naturally, thanks to the aggressive campaign for urban design led by Mayor Oh Se-hoon, these stories were conveniently excised from the public narrative of the Dongdaemun Design Plaza. In order to recover and record these stories, Listen to the City carried out the Memory Map workshop.

Park Eunseon: At the time, I thought it was wrong to try to squeeze this huge project of Cheonggyecheon into such a short schedule of seven months. I also thought it was wrong that no consideration was given to the people who worked in the area. And despite the scale, no one seemed to be taking any steps to document this massive civil engineering project. So I took it upon myself to start documenting it. Keeping in mind the issues of perspective when documenting the history of a city, I focused on the street vendors, asking why they came to Seoul, how they began their business, and what happened at the time.

Since their establishment in 2009, Listen to the City has shown persistent interest in issues of gentrification and development, seeking especially to help people who have been backed into a corner by the state and city. The group believes that the city does not belong to any individual (or small group), but rather that it is public property that must be publically managed. Park and her colleagues have also stressed the need to stop thinking of land purely as real estate, and to instead consider its non-monetary value.

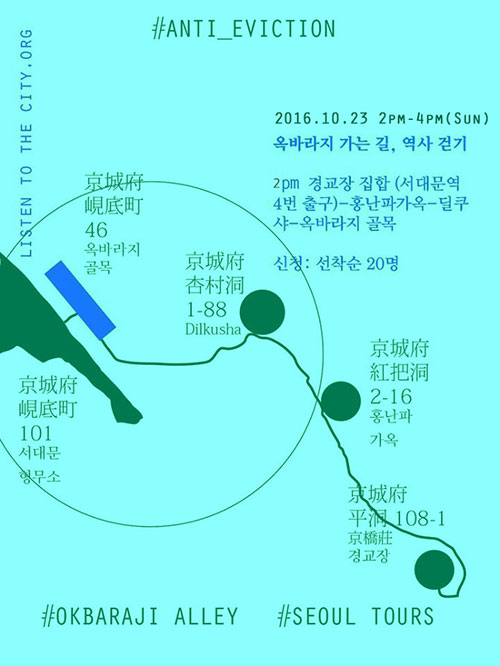

Listen to the City, 〈Okbaraji Alley〉, 2016.

Listen to the City, 〈Okbaraji Alley_Seoul Tours〉, 2016.

From the outset, Listen to the City demonstrated their commitment to helping society through action. When the popular restaurant Gungjung Jokbal, an institution of the Seochon neighborhood, was threatened by gentrification, the group did not merely voice their disapproval; they went to the restaurant to prevent the demolition. They were also deeply involved with efforts to resist the demolition of homes and other buildings in Okbaraji Alley near Seodaemun Station, a low-income area with a significant political history. The neighborhood originated from makeshift houses where the families of Korean independence activists once stayed while caring for their relatives, who were imprisoned in Seodaemun Prison under Japanese colonial rule (“okbaraji” means “to take care of a prisoner”). Since the early 2000s, major construction companies have been vying to “redevelop” the area, and plans are now underway to build a huge apartment complex there. In addition to leading conferences and organizing tours of the area, Listen to the City meticulously archived the campaign to demolish Okbaraji Alley—including documenting the forced eviction of residents on May, 17, 2016—through their video 〈Okbaraji Alley〉 (2016).

Jang Hyeonuk: I was informed about Okbaraji Alley by one of my friends, who is an activist fighting to preserve the neighborhood. I was instantly drawn to the inherent charm of the area, and I felt that such a space should not be replaced by an apartment complex. So I also became active in the movement.

Park Eunseon: Starting in late 2015, the construction companies moved in quickly and began the redevelopment of Okbaraji Alley. By January 2016, a considerable part of the neighborhood had already been demolished. I proposed to the Seoul Metropolitan Government that Okbaraji Alley be nominated as an Urban Regeneration Project, because of its rich history of stories. Although they seemed to support the proposal, the city demanded concrete evidence for preserving Okbaraji Alley. By going without sleep for a few days and nights, we were able to quickly collect and submit historical evidence about Okbaraji Alley, including newspapers from the 1920s through 1940s. But we were then told that it was too late. Even though city development is a public project, the city did not take social responsibility. Through this process, I came to realize how male-centric history has been, and how important it is to record the history of ordinary citizens, not just famous people.

Instead of simply delivering their messages on a canvas, Listen to the City expresses them through workshops, archives, videos, and other time-consuming formats. Working closely with residents to create archives, improve communication, and organize seminars, they directly confront social problems at sites that many people have become “desensitized to because they do not go there.” Rejecting superficial and deceptive art, Listen to the City stimulates discourse by meeting people and having conversations in workshops and seminars. Reiterating this approach, Jang Hyeonuk claimed that the group’s work consists primarily of striking up a conversation. By leading tours, Listen to the City bring us into the actual space. By organizing workshops, they help us meet people and discuss problems that we were not yet aware of. By joining resistance movements, they form genuine solidarity with those affected by urban development. In these and many other ways, Listen to the City records the stories that people cannot quite put into words.

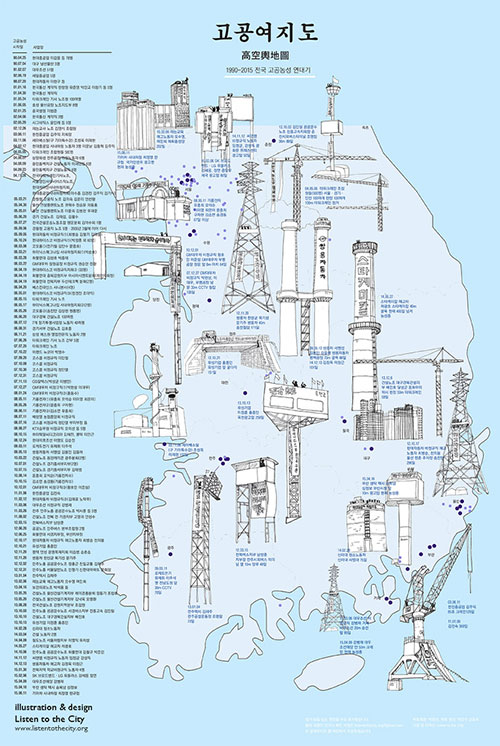

Listen to the City, 〈High Altitude Sit-in Demonstration in South Korea〉, 2015.

What Is Happening in Korea

Listen to the City also ventures beyond the boundaries of Seoul to investigate issues in other parts of Korea. It has been said that Koreans today have no values, aside from real estate. Failing to grasp the meaning of happiness, many Koreans chase a comfortable life by spending money and wasting resources. In the name of development, the state sprints towards its short-sighted goals, letting the siren song of big capital drown out the cries of the people. Korean society has been so devastated by the blind greed of money-grabbing corporations and politicians that our entire national identity is now at risk. As we all know, many things can be lost in an instant, but it takes much longer to recover them. Those who have lost their jobs, their homes, and their agency are forced to shout louder, fight harder, and persist time and time again, in order to get through to those who refuse to listen.

In their work 〈High Altitude Sit-in Demonstration in South Korea〉 (2015), Listen to the City documented demonstrations that were held at high-altitude sites throughout the country, from 1990 to 2015. As explained on the group’s website, the people who were forced to hold these demonstrations had been directly affected by various forms of corporate oppression and abusive labor practices, such as temporary contracts, indirect employment, illegal layoffs, and even false closures. The work resonates with the stories of those who climbed to the highest points in the country to shout at a society that refused to hear them.

Park Eunseon: Everyone feels life is difficult in Korea, so most people aren’t interested in labor issues, and have little sympathy for protesters. As an activist, I’ve come to realize that Koreans prefer to keep art separate from life. But I also understand that nothing will change without people who fight and resist. This is not only true of neighborhood demolitions or labor issues. But Korean people have never been trained to listen to the voices of the powerless. They’ve never done it before, because they couldn’t afford to. I felt like, if someone speaks out of desperation, then I should listen. Then I thought that a whole group was needed to listen.

The work includes a schematic map of Korea that is densely filled with various high-altitude demonstrations of the past. But only some of the recorded demonstrations are indicated on the map, reminding us that Korea is a place that often ignores the stories of the Other. By refusing to listen to counter opinions and excluding the voices of others, a handful of people have transformed the country of Korea to suit their own selfish desires. 〈High Altitude Sit-in Demonstration in South Korea〉 visualizes the voices of ordinary citizens—their “shouts in the silence”—which have been muted in the name of the nation-state.

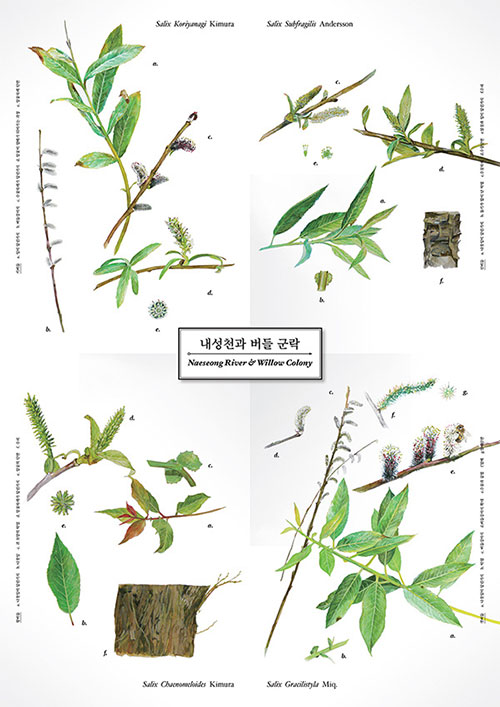

Another work by Listen to the City that fills a similar role is 『Illustrated Guide to the Ecology of Naeseong River』, which confronts the Four Major Rivers Project, a massive undertaking to restore several large rivers, which caused significant damage to the landscape of many affected areas. Carried out from 2009 to 2012, the Four Major Rivers Project was the primary engineering project of the administration of Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013), who became president after his term as the mayor of Seoul.

Park Eunseon: In 2009, while I was conducting a field survey, I met Monk Jiyul, who was very familiar with the Naeseong River before the Four Major Rivers Project took place. By that time, the river had already been completely devastated, and they had started working on the riverbed. The government repeatedly said that the project was 90% complete, so any attempt to stop it would just incur more losses for the country. But the Four Major Rivers Project was such a huge project that no one, including those in the government, could possibly understand its effects. Witnessing this situation, I kept researching what was wrong with the Four Major Rivers Project.

Naeseong River

To create their book 『Illustrated Guide to the Ecology of Naeseong River』 (2014), members of Listen to the City regularly went to monitor the conditions of the Naeseong River, documenting the destruction of local ecosystems. In addition to recording the changes to the river, the book was also intended to give the group enough standing to file an environmental lawsuit, a right that ordinary Korean citizens do not have. In the preface, the group wrote, “Until the river was completely ruined, our society did not pay much attention; the essence of the problem is the death of our society, if we fail to respond to the death of our environment.” This preface is an indictment of everyone who glimpsed news reports about the Four Major Rivers Project, but then never gave it a second thought. Along with their book, Listen to the City also led workshops about the project and produced the videos 〈Naeseong River〉 (2012) and 〈Sand Water Filter at Naeseong River〉 (2015). Then for the exhibition 《Objectology II: City of Makers》 (2015, MMCA), they exhibited miniature paintings of species that were in danger of extinction, along with water filters made with sand from the Naeseong River.

Listen to the City, 『Illustrated Guide to the Ecology of Naeseong River』, 2014.

Listen to the City also joined in the movement to support the people of Gangjeong, Jeju Island, whose lives have been turned upside down by the local construction of a U.S. naval base. Despite massive protests, the construction of the naval base was recently completed, but the people of Gangjeong remain determined not to allow their home be defined as a military site. Refusing to submit to the government’s demands, they have declared Gangjeong to be a town of life, peace, and culture. Joining the fight, Listen to the City published 『Hello, Gangjeong』, which documents the history and current status of the town and its citizens. Despite their surface differences, all of the sites that Listen to the City has supported (i.e., Okbaraji Alley, Naeseong River, and Gangjeong) have at least one thing in common: people forced by the government to relocate. Hence, the group recently produced its video Placelessness, which documents stories from all three sites. Jang Hyeonuk said that he wanted to talk about people who had been displaced by the state—especially those who refused to leave—and the places that they lost.

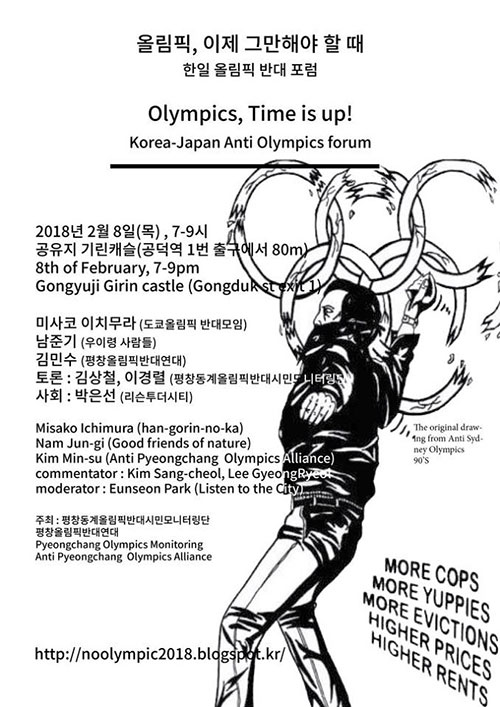

Listen to the City, "Anti-PyeongChang Olympics Alliance Forum," 2018.

More recently, Listen to the City rallied against the 2018 Winter Olympics through its “Anti-PyeongChang Olympics Alliance.” Although most Koreans consider the PyeongChang Olympics to have been a success, the short-term achievements are already giving way to long-term problems. First and foremost, the environment of Mt. Gariwang, home to many unique animals and plants, suffered irreparable damage due to the construction of facilities and the use of artificial snow. Moreover, most of the profits from the games went not to local citizens, but to wealthy financiers who had snatched up real estate in the area when prices began to increase before the games. As Jang Hyeonuk explained, “The activists…and I shared a critical opinion of the Olympics, in terms of both the beginning of the event and the aftermath. We examined many issues related to the selection of the host city, constructing stadiums, and deciding who will oversee maintenance after the event.” While conceding the need for “healthy patriotism,” Park Eunseon argued “The Olympics are just an event organized by the state to stir up feelings of nationalism.” The group’s words and works force us to ponder the real meaning of the Olympics.

Listen to the City does not try to resolve problems by removing or destroying the institutions in power. Instead, they adhere to flexible ways of helping people understand and contemplate the true nature of social problems. Rather than quietly accepting the unsustainable and indiscriminate development of the state or city, Listen to the City seeks sustainable resolutions for problems that have already happened, with an eye towards preventing problems of the future.

Language for the Margins of Society

In 〈No One Left Behind〉 (2018), Listen to the City detailed the plight of disabled residents in Pohang after an earthquake hit their city in 2017. Since earthquakes are so rare in Korea, the country was not adequately prepared to deal with such a disaster. In particular, the city of Pohang failed to provide competent assistance to its 26,000 disabled residents, who represent about 5% of the city’s population. In the video, various disabled residents share their testimonials of problems that occurred in the aftermath of the earthquake. For example, Heunghae Stadium, the designated shelter for residents, did not have any facilities or equipment for the disabled, and the television channel DBN (Deaf Broadcasting Network) was slow to inform viewers about the situation because of its limited budget.

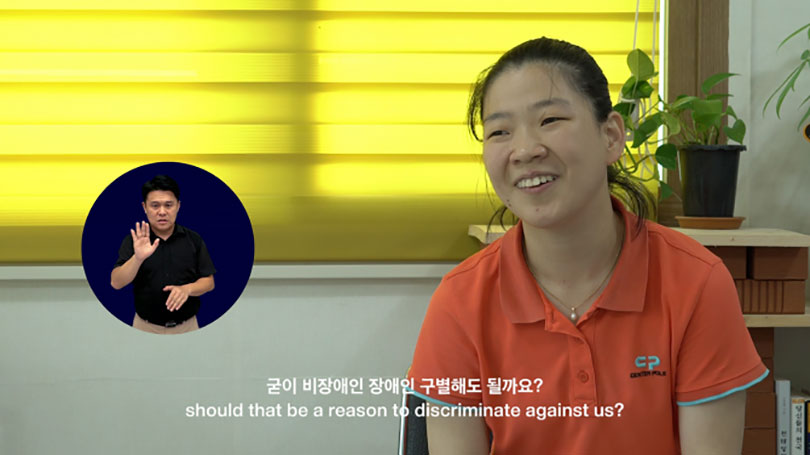

Listen to the City, 〈No One Left Behind〉, 2018.

If the city of Pohang has a disaster manual, who is it written for? In the wake of a national disaster, the speed of life-saving information should not be dependent upon a budget, or even worse, the conditions of the receivers. Observing these circumstances, Listen to the City interviewed many disabled people to learn about their problems and emotions related to the earthquake, and also organized workshops for disaster preparedness.

Park Eunseon: The effects of a disaster are not equal. Older people and those with less mobility are more prone to danger. Social minorities are especially vulnerable to disaster. We must think seriously about how to be better prepared for this. Some people have said, “If we can’t even effectively evacuate fully abled people, how can we possibly assist the disabled?” They’re basically saying that the disabled are destined to die in a disaster. Is it really okay to say that? This is a simple, but very important issue.

A woman in the video says, “We are just the same as everybody else. We might be a little slower to move or think, or we might not be as good at making quick judgments. But should that be a reason to discriminate against us?” The interviewees also emphasize the importance of being with other people in the aftermath of a disaster, to avoid feeling alone. Of course, this is true not only after a natural catastrophe, but also in everyday life, as we all try to navigate our own psychological issues. In the video, Park Eunseon says, “Just as feminism took a long time to establish its own language, we need to build the language of minorities at the periphery of society.” Through works such as 〈No One Left Behind〉, Listen to the City is working to create and visualize such language.

In her book 『Time of Failed Country』, the cultural anthropologist Jo Han Hyejeong wrote, “New possibilities emerge not from the center, but from the edges of society….Those who recognize extreme situations causing disagreement initiate a revitalization movement in order to save themselves, which then triggers a massive transition.” Exemplifying this process, Listen to the City confronts problems that are taking place at the periphery of society by speaking out in diverse ways to change our ways of thinking and improve the overall status of our city and nation. Listen to the City believes that we must change our attitude and awareness in order to ensure that those with disadvantages receive every advantage. Like a hammer, the works and voices of Listen to the City constantly pound against the rigid walls of our society, forming cracks and opening possibilities for a new way of life. Listen to the City has been able to achieve this by living up to their name; they perpetually listen to the city and the people who live there. Like the sunset, they reveal the sights, sounds, and voices that have been hidden within the blinding light of day.

* This piece is part of a series focusing on four artists for a visual arts criticism/medium matching support program by the Korean Arts Management Service.

1)See the website of Listen to the City: http://www.listentothecity.org/About

2)Shin Hyeonju and Yi Giung, eds, 『Seoul and Its Gentrification』 (Paju: Prunsoop, 2016), p. 74.

3)Do Hwaji, 『Fragments of Memory』 (Gongju: Keungeul Sarang, 2016), p. 228.

4)Yi Mihye, “Ecology of Wetland I,” ALLURE, accessed November 15, 2018, http://bitly.kr/eWa4.

5)Gangjeong Peace Trip, 『Hello, Gangjeong』 (Seoul: Listen to the City, 2017), p. 8.

6)Anti-PyeongChang Olympics Alliance, “We Don’t Need Olympics Calamity,” (Seoul: Listen to the City, 2017).

7)See http://www.listentothecity.org/No-One-Left-Behind-1, pp. 46-48.

8)Jo Han Hyejeong, 『Time of Failed Country』 (Paju: Saiplanet, 2018), p. 15.

Juwon Park

Art Critic