Dawn of a New Video Culture: Korean Single-channel Videos of the Late 1990s and Early 2000s (Part Ⅱ)

From his very first exhibition, RYU Biho’s promise as a digital media artist was evident. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, as the Korean government intensified its focus on information technology, more and more artists began seeking to acquire the latest technological breakthroughs and incorporate them into their artworks. What sets RYU’s work apart from the rest is its transitional quality, announcing itself as “digital” despite employing a minimum of technology. Moreover, rather than deriving influence from past generations, RYU established a singular post-genre quality through independent experimentation.

0.How is a young artist affected when his or her first exhibition is a smash success? Reflecting the fever for digital technology that swept through Korea around the turn of the twenty-first century, early articles about RYU Biho (b. 1970) dubbed him the “digital kid” and the “media-savvy artist of the new generation.” Seeking to bounce back from the financial crisis of the late nineties, the administration of President Kim Dae-jung began actively supporting IT companies and entrepreneurs, while setting up the infrastructure to provide high-speed internet throughout the country. Thanks to such policies, the number of high-speed internet subscribers increased by a factor of 700 between 1998 and 2002, while the widespread availability of Microsoft Windows in public agencies, schools, companies, and homes paved the way for the IT era.1) The art and culture field was quick to respond to the government’s measures. To usher in the new millennium, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism pronounced 2000 to be the year of “New Art,” launching an initiative to support integrative and interdisciplinary performances, installations, and collaborations by New Media practitioners applying cutting-edge technology.2)

As has often been the case in Korea, these changes seem to have been driven less by a natural response from the internal art scene and more by outside factors prompting members to race towards a new goal, without fully considering the purpose or direction of the change. The booming rise of New Media and digital technology culminated with the debut of Media City Seoul (2000), Korea’s first-ever media biennale. Under the theme “City: Between 0 and 1,” the debut edition of Media City Seoul took over sites throughout the city, including three venues in Gyeonghuigung Palace and nearby areas, thirteen subway stations, and forty-two outdoor electronic displays. The exhibition offered a resounding answer to the question, “What is New Art?”

However, while Media City Seoul and other government-led exhibitions grabbed the public’s attention, efforts to implement IT and promote cultural content were causing more fundamental changes at the ground level. For the first time, commercial galleries and cultural institutions - including the Korea Culture and Arts Education Service and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art - created their own official websites. Meanwhile, motivated by both practical convenience and commercial gain, various profit-seeking sites were also launched, greatly facilitating people’s ability to search and archive information about artists and exhibitions. The two most prominent examples were neolook.com - which dominated the 2000s as the go-to site for exhibition support and records, as well as up-to-the-minute industry news - and daljin.com, which established the industry’s premier databases for artist biographies and annual publications. The proliferation of online activity also fomented an unprecedented culture of debate, with heated exchanges and blunt critiques related to major exhibitions becoming commonplace on platforms such as the site of Forum A (consisting mainly of members from Alternative Space Pool) and the webzine Mudaeppo (run by independent curator Ryu Byung-hak).

These trends did not escape the notice of art journals or educational institutions. The February 2000 issue of Wolganmisool featured the debut of Woo Hyo-ki’s “Digital World” column (entitled “A Day in the Life of a Yale University Student, Digitally Transmitted”), which continued for sixteen installments through December 2001. In January 2002, the column evolved into “The Digital in Art,” featuring short articles about digital art by different writers. The widespread enthusiasm for the “video generation” and the “MTV sensibility” soon led to a zealous interest in digital technology, web art, and game art within Korean art scene.3) In response, around 2000, many universities began establishing programs or departments for video or media studies, including the Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Advanced Imaging Science, the department of global media studies at Soongsil University, and the graduate programs in video studies at Yonsei and Sogang Universities.4) Notably, many prominent media artists were educated—or reeducated—at these programs. Through all of these conditions, Korean society was perfectly primed for the first solo exhibition of RYU Biho, whose futurist and cyberpunk works were immediately acclaimed as the ideal expressions of the new era.

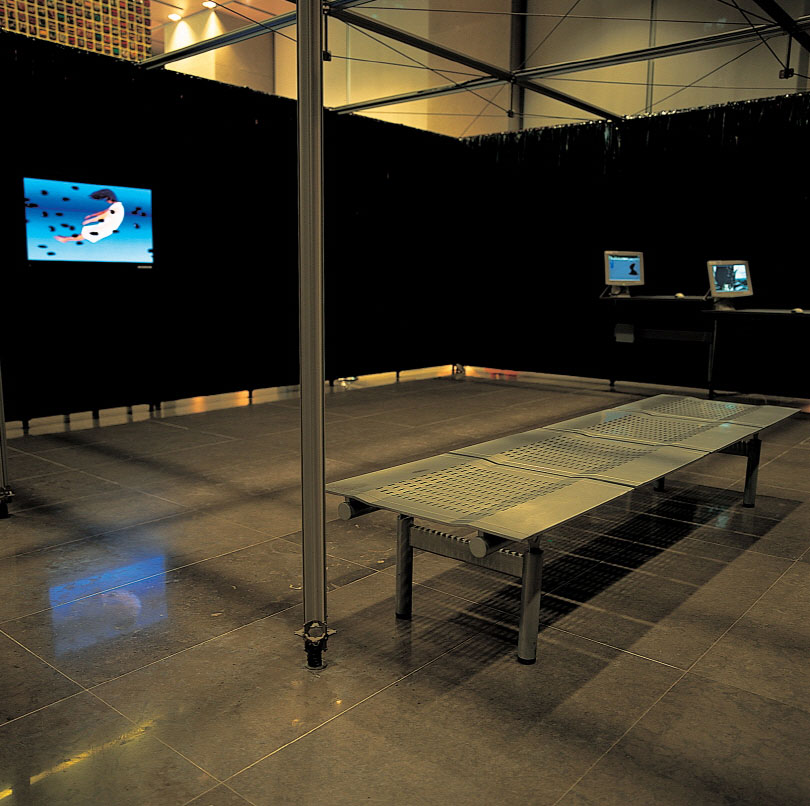

Tableau from the 《Steel Sun》 exhibition (2000) at Gallery Boda.

1.Interestingly, RYU’s first exhibition 《Steel Sun》, which caused such a sensation in the Korean art world, almost never happened at all. Like many young artists, RYU was introduced to the art world largely by accident. After plans for another exhibition fell apart, a curator from Gallery Boda contacted curator Noam Kim looking for a replacement. Kim, who was acquainted with many young artists at the time, recommended RYU primarily because he knew that the young video artist had enough finished works for an exhibition on short notice. The result was 《Steel Sun》, a New Media installation exhibition consisting entirely of digital prints and video. Given the overall enthusiasm for video and multimedia at the time, it is not especially surprising that the debut of a new artist would generate some sense of synergy. More notable, however, were exactly what the “new sensibility” or “high-technology art” describing RYU is. Analyzing the subject and the level of technology that were adopted for artworks described as “New Media” of that time are the key elements for identifying peculiarity of Korean media art.

Despite the rhetoric, all of the works presented in 《Steel Sun》 were actually hand-produced with basic technology. Having no access to multi-channel editing equipment, RYU produced the seven-channel video installation 《Steel Sun》 (2000) by carefully planning and storyboarding the images for each channel, positioning the objects according to his plan, and then repeatedly filming them. This “analog” process can be seen in the timeline drawings for 1984 (2000), a three-channel video that shows eleven people (three on one channel, five on another, three on a third) performing various actions (e.g., running, resting, standing still, tapping their feet) at different intervals. The left-right symmetry of the movements was achieved by meticulously timing and coordinating the actions of the performers. To this end, RYU provided each performer with a timetable dictating when each action was to be performed; the same table was then used to edit the videos and manually synchronize the images. The use of cathode-ray tube monitors, rather than flat screens, further illustrates the transitional nature of 《Steel Sun》, which was still tethered to the analog, even as it proclaimed the digital.

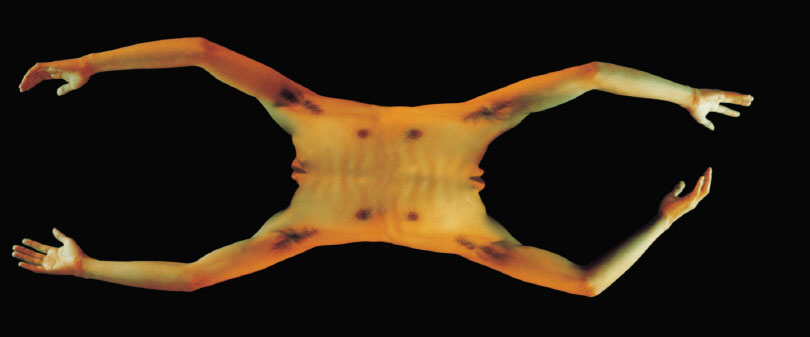

Inspired by a multi-channel karaoke machine, the four-channel installation work 〈Morph〉 (2000) uses a simple morphing effect to produce artificial images that transform in unpredictable ways. But even this effect was achieved with a relatively simple technological process, with corresponding points on different images used to produce an intermediate value in the rendering process.5) Indeed, many of RYU’s works from this time (including 1984 and 〈The Mass Calisthenics〉 (2000)) were made with free software that could create a moving image from two still images. More akin to a collage of still images than a video, these works belong in the same trajectory as the digital prints that RYU was also producing at this time, such as 〈Multi-Media Man〉 (2000) and 〈Genome〉 (2000). Both of those works are Photoshop composites of the artist’s own body, thus presenting a spatial transformation that corresponds to the temporal quality of 〈Morph〉. RYU employed a similar process for 〈Hi, Guys〉 (2000), an animated video of engravings by Francisco Goya. Here, the minute gap between frames is strategically used to create the illusion of movement, such that the heads and limbs of execution victims appear as slow blurs.

RYU Biho, 〈Genome〉, 2000. digital projection, 150x150cm.

In these early works, instead of applying the inherent properties of video (such as editing) or focusing on narrative, RYU approached video as an extension of photography or painting. By experimenting with the composition and mise-en-scène of a given image or the texture of multiple images, he used video to explore the spatial, rather than the temporal, linkages between images. Even in his multi-channel works, rather than presenting a flow of independent images (i.e., time) through each channel, he meticulously conceived the interaction of the various channels in service to the overall spatial composition.

2.Like many art school graduates at the time, RYU perceived videos primarily as images. The artist himself described his early works as “forms representing the temporal expansion of pictorial images.”6) In this sense, the texture and ambiance of RYU’s works clearly differ from those of Sejin Kim, an artist of the same generation. While Kim had some interactions with other video artists, such as Hong Sung-min and Ium, her conception of video was largely acquired outside of the art field, particularly through her employment at a computer graphics company. Emphasizing visual effects over concepts, her works are characterized by highly sensual images, achieved through rapid cutting and distinctive audio-visual rhythms. However, Sejin Kim’s case is quite exceptional among the young Korean artists who began working in video and New Media around the turn of the twenty-first century. At the time, there were as yet no art schools in Korea offering curricula in video or media art, leaving young artists to train themselves via acquaintances or self-study. RYU Biho transitioned to video after graduating from the painting department of Hongik University, exemplifying the typical route to media art at the time.

Like Sejin Kim, RYU Biho’s interests in video were closely tied to the popular video culture of the 1990s. In addition to television and commercial advertising, RYU was also strongly influenced by the indie and arthouse films that began to be shown at cinematheques in Korea’s university neighborhoods around the early 1990s. As a student, RYU enjoyed watching art films with his close friend Jae Oon Rho, who is one of representative video & new media artists of that day as well, at Filmspace 1895, a theater near the rear gate of Hongik University.7) Boasting a collection of thousands of rare art film VHS tapes, Filmspace 1895 played a pivotal role in the development of Korean cinephile culture, regularly hosting retrospectives of major directors, along with lectures by critics and directors, such as Jung Sung-il, Lee Yong-kwan, Lee Kwang-mo, and Jeon Yang-joon.8) Indeed, many young artists of the time became versed in film and video not through commercial theaters, but rather at cinematheques and alternative spaces such as Filmspace 1895, which often showed art films from pirated videotapes.

While he was developing his overall sensibility of video through art films, RYU Biho learned about the actual techniques and equipment from older friends and colleagues. A key figure in this regard was Lee Sang-yoon, an early adopter of flash animation, web design, and video editing in the late 1990s. In 2000, Lee founded Blind Sound, a platform for web art that became a key networking hub for young digital artists of the 2000s. In the late 1990s, Lee taught video editing and computer graphics to his younger colleague Kang Young-min, who designed graphics and managed websites for Lee’s projects. Kang then imparted these lessons in video equipment to his classmates RYU Biho and Jae Oon Rho.9) Ultimately, RYU’s early method of using video to connect still images can be attributed to two primary factors: his university education in painting and his limited access to video technology. As mentioned, RYU’s interest in video was certainly fueled by a larger social trend, but due to his university education, he was still much more familiar with composing still images than editing films or videos. In addition, as a young student and artist, he had almost no access to the expensive equipment needed to produce sophisticated video effects.

Looking back at the history of media art in Korea, the representative video artists of each era seem to have been spontaneously generated from their contemporaneous social conditions, showing little or no affinity to their predecessors. To be specific, the video works of Kim Hae-min, Yook Tae-jin, and Kim Young-jin in the mid-1990s bear little resemblance to those of Oh Gyeong-hwa, Kim Jae-kwon, and Lee Won-gon in the 1980s, which are themselves completely distinct from the video works of Park Hyun-ki and others in the 1970s. Continuing this pattern, RYU Biho and his fellow young video artists of the late 1990s completely diverged from the video artists of the mid-1990s. While this phenomenon can be partially explained by the conceptual divergence between the video artists of the mid-1990s (based on philosophy and existentialism) and the late 1990s (based on Western art films and pop culture), there are various practical factors that should not be overlooked. First and foremost, with the medium of video still in its fledgling stage, the lack of university lectures or classes made it almost impossible for each generation to convey its mantle through academia. Furthermore, Kim Hae-min and Yook Tae-jin were based in Daejeon and had not attended a major university in Seoul, giving them little access to the academic environment of Seoul. As a result, RYU Biho and his peers came to video work through external influences—such as study abroad or self-training—without any ties to the previous generation.

With 《Steel Sun》, RYU was immediately anointed as one of Korea’s premier media artists of the time. As a result, he was soon bombarded with invitations to participate in various media art exhibitions, which experienced a boom.10) But what was it about RYU’s work that caused such a sensation? In contrast to their sci-fi surfaces and formal impressions of “high technology,” the artist’s early works are actually quite somber and serious. Taking its name from the 1980’s Korean political activist group’s jargon “steely line-up,” 《Steel Sun》 is a dark comic piece satirizing the impotence of individuals living under absolute authority, symbolized by the sun. The characters flail about in a kind of “techno dance” before disappearing altogether, their movements recalling feeble spasms of individual resistance within a totalitarian culture. Similarly, in 1984, people dressed in black run around aimlessly and periodically stop, embodying the anxiety of individuals thrust into the blind competition of a fascist society. As another parody of collectivism, 〈The Mass Calisthenics〉 shows people in red workout clothes repeating the same actions before finally merging into a single unit. All three of these works have a distinct left-right symmetry, reminiscent of Rorschach inkblots, which may be read as an allusion to the regimented “Orwellian” society of 1984 or the uniform landscapes of the fascist city in Leni Riefenstahl’s film 〈The Victory of Faith〉 (1933). Notably, this “critical interest in real society”11) runs counter to most conceptions of Korea’s “video generation,” which is typically seen as responding to images in a sensual way.

Representing the tail end of the “386 Generation” (the generation of young political activists who led the democracy movement in the 1980s and early 1990s), RYU grew up under the repressive military regime and was experienced group study in university that was akin to mass study. These experiences clearly had a profound effect on his work, forming a grand narrative that suggests a historical role for art.12) To this day, however, these aspects of RYU’s art have been largely overlooked in favor of the technological forms of New Media and the metallic texture of his composite images.

RYU Biho, 〈From A Yellow Ground〉, 2001. digital image.

Panorama of 《A SOMNAMBULANCE》 exhibition (2001) at Ilju Art House.

3.This focus on the form of RYU Biho’s works, rather than their content, as previously noted by Kang Su-mi, is in line with the overall social climate of the time, as Koreans eagerly anticipated the redefinition of visual culture that would result from the inevitable shift to digital technology.13) Within this atmosphere, Korean artists were highly motivated to provide the sort of technological, sensual images that the society was demanding, leading to an overemphasis on surface. But the perception of RYU as a New Media artist focusing on technology was also related to his own experimental dalliances with various media. His first solo exhibition alone included digital prints, animation, and multi-channel video installations, and he has since expanded into web art, virtual reality, computer simulation, and interactive performances with audio-visual technology.

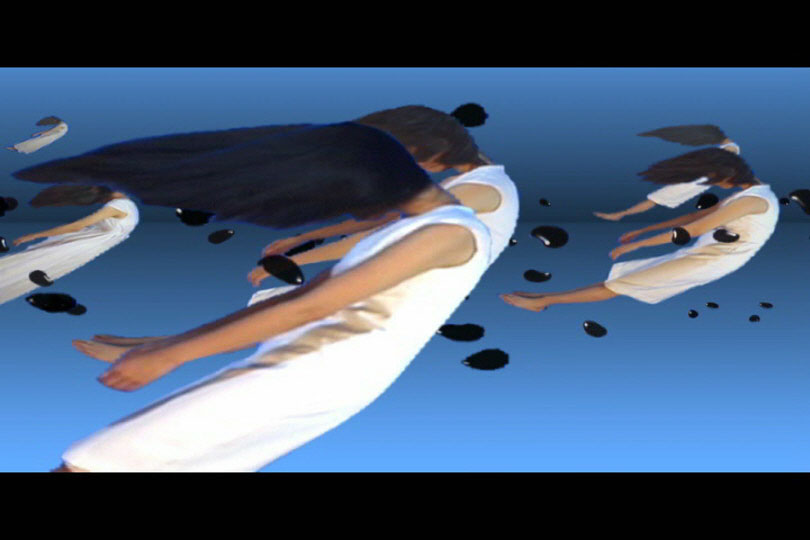

The works of RYU’s second solo exhibition—《A SOMNAMBULANCE》 (Ilju Art House, 2001)—show clear formal differences from the simple morphing of still images that marked the works in 《Steel Sun》, presented just one year earlier. For 〈In Silence〉 (2001), RYU used After Effects (a computer graphics program) to insert layers of black droplets between still images, resulting in a type of floating effect. Also, for 〈A Yellow Ground〉 (2001) and 〈Dream of a Boy Drowned on a Bright Day〉 (2001), the artist used Apple’s QuickTime VR Authoring Studio to create a virtual sphere of images that viewers could navigate with a mouse, thus creating a 360-degree panorama reminiscent of virtual reality.14) RYU adopted a similar panoramic format for 〈The DMZ—A Line of Beauty?〉 (2001), presented in the web exhibition 《DMZ on the WEB》 (2001), blending real images with graphics to create a fantastic virtual landscape. But no matter what the eventual format, RYU’s overall approach to video composition has not changed. Whether producing videos or VR simulations, he typically applies a collage method, in which he manipulates the colors of photographs or uses Photoshop to draw on images and arrange them in virtual space.

RYU Biho, 〈The DMZ—A Line of Beauty?〉, 2001. digital image.

RYU Biho, 〈A Silence, 2001. single-channel video installation, 4:45.

Amidst the veneration of hybridity that marked the early 2000s, such multimedia experiments cemented RYU Biho’s status as a post-genre New Media artist. Looking back, however, RYU’s early pieces seem far too painterly and lyrical to qualify as a New Media works showcasing technology. To this day, it is difficult to say whether they should be classified as video or media art. In both his single- and multi-channel works, the emphasis on image and the experimentation with media carry equal weight. For instance, RYU was invited to take part in the Ilju Art House exhibition 《Re-mediating TV》 (2002) as a video artist, but his contribution to Art Center Nabi’s 《Liquid Space》 (2003)—part of the Resfest Digital Film Festival—was more likely considered to be media art.15) For the latter event, he worked with the electronic musician FuturEyeTronica to produce 〈The Implicate Order〉 (2003), in which sounds are generated from a 3D simulation. As a young artist eager to test the expressive possibilities of different media, RYU took full advantage of the post-millennium embrace of genre flexibility to experiment in various media, rather than restricting himself to video alone. Whether showing videos alongside artists of other genres at the Independent Art Festival (now known as the Seoul Fringe Festival), taking part in a Korea Electro-Acoustic Music Society workshop on the Max/MSP sound interaction program, or collaborating with electronic musician Choi Young-joon, Biho RYU’s activities in the early 2000s exemplify the path of a multimedia artist. Moreover, after running the study group “Art Action through Hacking” (2001) on art-society-media with artist Yangachi, RYU went on to establish “Parasite-Tactical Media Networks” (2004-2006), an organization that sought new ways of affecting society through media. Until his 2015 exhibition 《In My Sky at Twilight》 (Sungkok Art Museum) that marked a return to the video format and to more intimate, personal content, he had kept going experimentation with media forms linking art and society for a long time. Perhaps this long detour was the price to pay for the legitimate child of the post-genre, multimedia atmosphere around the turn of the millennium.

※ This article was published in the January, 2019 release of Wolganmisool Magazine as part of the Visual Arts Critic-Media Matching Support Project by the Korea Arts Management Service.

1)http://www.zdnet.co.kr/news/news_view.asp?artice_id=20090823171914&lo=zv41

2)As defined by Korea’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, “new art” was considered to be “experimental and creative art involving new attempts within existing artistic genres”; “art as a new category manifested through post-gentrification and genre integration”; “new forms of art based on new means of expression”; and “adventurous and provocative experimental art aimed at presenting traditional artistic genres and expression in a way suited to modern sensibilities.” (http://www.joongdo.co.kr/main/view.php?key=200001010053).

3)Articles reflecting this interest include “Special Feature: Art & Digital,” Art Monthly, May 2001; “Special Feature: Game Art,” Art Monthly, April 2002; and Kim Dal-jin, “Internet art sites according to 22 culture and arts practitioners,” Art Monthly, December 2001.

4)Ban Ejung, Korean Contemporary Art, 1998-2009 (Seoul: Mimesis, 2018), p. 114.

5)Interview with RYU Biho, December 4, 2018.

6)RYU, interview.

7)RYU, interview. Considering that Filmspace 1895 existed from 1989 to 1993 and RYU entered college in 1990, we can figure out that RYU visited Filmspace 1895 from 1990 to 1993.

8)http://www.cine21.com/news/view/?mag_id=66188. In addition to Filmspace 1895, other major cinematheques driving film culture in the 1990s included Ssiangssie, Culture School Seoul, Film Love, and Inkel Art Hall.

9)RYU, interview.

10)Related exhibitions include Media Art 21 (Sejong Gallery, 2000; curated by Lee Won-gon), DMZ on the WEB (www.livedmz.net, 2001), and Re-mediating TV (Ilju Art House, 2002).

11)Kang Su-mi, “Accidental and Intermediary Art-Social Tool,” SeMA Nanji Residency Sourcebook (Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, 2011), p. 90.

12)RYU interview. The artist stated that reading list of group study activity included everything from Arnold Hauser’s Social History of Art to major Eastern and Western books on the history of science, culture, and philosophy, as well as Sung Wankyung’s public art discourse, Mexican muralism, and Park Je-dong’s political cartoons published in newspaper Hankyoreh.

13)Kang, p. 88.

14)RYU, interview.

15)For this performance, Korean media artists and electronic musicians collaborated on works using a game engine program developed by the Belgian media art group LAB [au]. Other participants included Kwon Byung-jun and Ryu Han-kil.

Hye Jin Mun / Art Theory

Hye Jin Mun is a critic, translator and lecturer at Korea National University of Arts. Her major interest is technology-based media and cross-media study in contemporary art.