Mark Rappolt considers the precarious nature of Suki Seokyeong Kang’s work – now on view at Mudam, Luxembourg, through 1 April

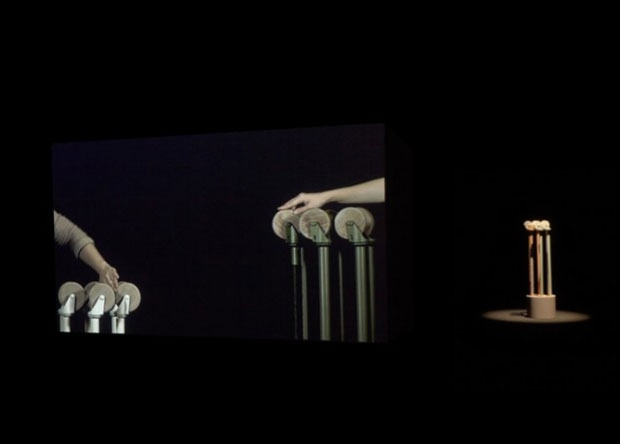

Suki Seokyeong Kang, Installation view at Mudam, Luxembourg, 2019. Photoⓒ Albrecht Fuchs

One of the many ways in which one might seek to define contemporary art (assuming that you’ve ruled out the most obvious ones to do with temporal immediacy – and let’s face it, something like Wikipedia’s ‘contemporary art is the art of today, produced in the second half of the 20th century or in the 21st century’ is both vague and contradictory, and a lot less than specific) is to say that it describes an artform that moves outside the restraints of any single medium. Because today the world belongs to those who wish to resist any attempt to define and pigeonhole them (despite the persistent attempts of governments around the world to do precisely the opposite). By that standard, Suki Seokyeong Kang is a contemporary artist. And other people, notably the curator Sungwon Kim, have written elegantly about her in these kind of genre-busting terms.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Black Mat Oriole〉, 2016-2017. Mixed-media installation, dimensions variable. ⓒthe artist, Kukje Gallery, Seoul, and Tina Kim Gallery.

Kang is a painter who produces sculpture, a sculptor who tends to organise her work as installation and eschews static form. She embraces both representation and abstraction; some might call her a performance artist, others a designer. So far so little: all this appears to tell you something, while actually revealing nothing. If the medium is not the focus, then it must be the message, you cry! There’s nothing more contemporary than that! And yet any discussion of the ‘message’ in Kang’s output is no more straightforward than the definition of her medium. That, at least, was certainly my experience of bumping into her 〈Land Sand Strand〉 (2016-2018) at last year’s Liverpool Biennial (another version is on show in the Arsenale at this year’s Venice Biennale). Even after I had picked up an ‘activation manual’ that contained stick-figure instructions for positions and movements of the body and a maplike grid. But sometimes a work of art can intrigue you not because it articulates something that is instantly clear or self-evident, but precisely because it evades easy readings or quick definitions.

Suki Seokyeong Kang, 〈Black Mat Oriole〉, 2016-2017. Mixed-media installation, dimensions variable. ⓒthe artist, Kukje Gallery, Seoul, and Tina Kim Gallery.

Kang studied oriental painting (‘very typical, traditional’ in the artist’s words) at high school and then at Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul, where she is currently a professor of Korean painting. Following these studies in her homeland she completed an MA in painting at the Royal College of Art in London, graduating in 2012. 〈Grandmother Tower〉 (2011-2013) is a foundational work and has been followed by an ongoing series of similarly titled sculptures (the latest of which is on show in the Central Pavilion at the Biennale) that evolve the initial theme. The latter was originally developed at the time Kang’s grandmother, who had been a central force in her life to date, was dying, and was designed to mimic her height and posture (later versions have reached greater heights) as she arrived at the point at which her body could no longer support its own weight. (Each unit of Kang’s work is still designed not to exceed the average weight of a human body.) Its form is a leaning skeletal structure, constructed out of the variously sized, modular, drumlike frames of industrial dish carriers. It describes a form of seriality, but one that lacks precision and rigour. Each of the metal carriers is wrapped in coloured thread, or sometimes leather, that the artist has described as a reflection of the colour and glamour she saw in her grandmother, but which also provides the friction and grip that enables one unit to support the weight of another. The whole looks solid but precarious, static but on the brink of collapse, composed of lines but emphatically three-dimensional, safe but potentially dangerous. Paradoxical yet axiomatic, it has something to say, but it is what it is: a series of found objects rearranged and renewed, or a series of coloured lines, a demonstration of the action of and a reaction to the force of gravity. But equally its structure speaks of age and change, with an implied sense of rhythmic precision. This sense is even greater in later iterations of the work, such as 〈Grandmother Tower–tow #18-01〉 or 〈Grandmother Tower–tow #18-02〉 (both 2018), which further incorporate variations on a wheeled walking frame (which is also the basis of the 〈Circled Stairs〉 series, 2011–, in which walking frames are piled one on top of another to create the frame of a ladder or staircase) into the base of the tottering tower, and which are at times further activated by performers who preform choreographed movements or interact with the objects.

Work by Suki Seokyeong Kang is on show at Mudam, Luxembourg, through 1 April.

※ Click to Read the Full Article on ArtReview: Teetering on the edge(https://artreview.com/home/ara_autumn_2019_feature_suki_seokyeong_kang/)

※ This article was originally published in the Autumn 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia(https://www.artreview.com), by Mark Rappolt.

Mark Rappolt

Editor-in-Chief of ArtReview and ArtReview Asia