People / Critic

Synesthetic landscape and nonlinear narrative video work of Hwa Young Park

posted 31 Dec 2019After acquiring a love of film while at art school in Korea, Hwa Young Park began blazing a trail that is unique in the history of Korean single-channel video. One of the keys to her development as a video artist was her period of graduate study in the United States, where she had access to both works and equipment that were not then available in Korea. From her earliest pieces, Park has taken a pluralistic approach, using the complex interactions of different media to represent the existential response of individuals to irrational circumstances. This essay is the final installment in Hye Jin Mun’s series, “Dawn of a New Video Culture: Korean Single-channel Videos of the Late 1990s and Early 2000s in Wolganmisool.”

0.In the history of Korean single-channel video, few artists have taken a more divergent path than Hwa Young Park. By doggedly following her own instincts and voice, Park has constructed her own artistic world, one that exists outside of the universe of either the West, where she studied, or Korea, where she was born and now continues to work. Her art is truly sui generis, such that it cannot be placed neatly into any lineage.

With their non-linear narratives, dramatic staging, and post-genre formats, Park’s works were precisely what the Korean art world was craving in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a time when experimental works mixing media or genre were eagerly embraced. Having studied art and film in the West and participated in the promising PS1 international studio program, Park was a perfect fit for the Korean art world of the late 1990s, where narrative-centered single-channel videos were coming to the fore and young, globally minded artists were in high demand. True to form, Park’s first exhibition upon her return—《Accumulation of Dust》 (1997)—earned her instant acclaim as one of the leading video and media artists of the day. She began receiving invitations to major exhibitions and competitions at home and abroad, thus triggering a period of prolific activity. In the late 1990s, for example, Park was featured in 《Inside Out》 (1997), which introduced four South Korean artists to the US, jointly organized by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, and the University of Pennsylvania Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) 1; 《In the Eye of the Tiger》 (1998), a New York exhibition of ten avant-garde South Korean artists experimenting with new media2; 《The Visual Extension of Photographic Image—Reality and Fantasy》 (1998), a prominent exhibition of video, photography, and media art, organized to commemorate 1998 as the “year of photography and film” in Korea 3; and the second 《Shinsegae Art Festival》 (1998), which drew great attention by offering financial support to selected young artists, which was quite unusual at the time. 4

Like Yang Ah Ham (who studied with Peter Campus, the renowned pioneer of conceptual video art), Park began her video work as a student in the US. Since then, however, Park has been on her own trajectory, producing innovative works that bear little resemblance to anything that has come before or since, in either video art or film. Like many Korean university students at the time, Park developed a passion for film while attending art school in the early 1990s. She recalls seeking out rare films at a Chung-Ang University cult film festival and other venues.5 Her passion only deepened in New York, where she was suddenly exposed to a wealth of avant-garde works that were not available in Korea. While in New York, she regularly visited Kim’s Video, a rental shop specializing in rare and avant-garde films, and the Angelika Film Center, which offered an ongoing slate of indie films, with ranging over experimental films, performances and videos at multi-media library of the university.

Notably, however, Park’s film preference did not encompass many works by the conceptual video artists of the 1970s (such as Peter Campus or Vito Acconci), who were simply not to her taste. She has shown similar disinterest towards famous video artists of her own generation, such as Stan Douglas or Doug Aitken. Indeed, among the contemporary canon of video artists, only Matthew Barney piqued her interest as being “cinematic.”6 Instead, Park prefers the films of directors such as Andrei Tarkovsky, Krzysztof Kieslowski, Peter Greenaway, Wim Wenders, David Lynch, Chris Marker, Akira Kurosawa, and Alain Resnais, along with theatrical performances helmed by renowned directors such as Robert Wilson and Romeo Castellucci.7 In 1994, Park began producing her own experimental videos through a film production workshop at New York University’s School of Continuing Education (1994-1995). Rather than trying to absorb the previous currents or seeking to emulate models from art history, Park sought to develop her own language based on her subjective sensibilities, veering off the beaten path in a daring search for a new landscape unconstrained by boundaries of genre.

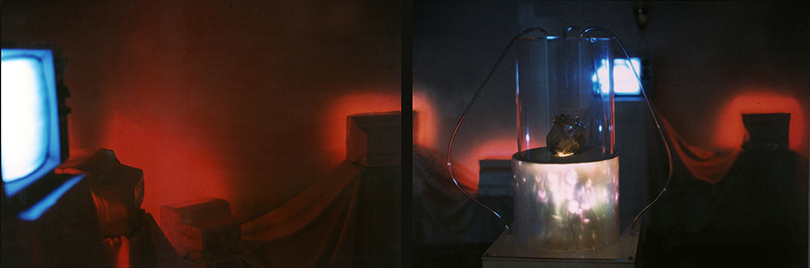

Hwa Young Park, 〈PULSE ROOM〉, 1994. multimedia installation consisting of lights, various AV equipment, and a motorized sculpture of a heart.

1.From the beginning, Park has adopted a multidisciplinary approach, creating works in which elements of various media intersect to express the ontological dilemmas of people struggling alone to subsist in an absurd situation.8 In her first solo exhibition 《A Legal Alien on Earth》 (1992), held shortly after she graduated from university, Park presented an array of works ranging from two-dimensional drawings, paintings, and lithographs to installations and outdoor public art. Looking back at her debut, the artist later said that she chose to produce installations, which could not be easily bought or sold, as a protest against the commercialism of the art world and society at large.9 The same mindset may have precipitated her transition to immaterial works, such as video and performance, which can only be experienced, rather than collected. As demonstrated by film and literature, works that do not rely on a material presence are often more suitable for eliciting various emotions and experiences in a wider range of people. Such an approach was ideal for an artist like Park, who always prioritized connection and communion.

Park first began showing time-based works at 《Incubator》 (1993), her first solo exhibition after beginning her overseas studies. Seeking to trigger a visceral, even revolting experience, Park presented an installation that mimicked the sensation of wandering through an organic body. Visitors to the gallery walked across a floor lined with plastic containing a squishy mix of gelatin and red dye, while listening to a doctor lecturing on heart disease, along with other sounds such as the beating of a heart, breathing, and air bubbles in water10. Through the combination of the soundscape, the dreamy lighting, and the gelatinous texture beneath the feet, the entire space was transformed into an immersive stage, in which the visitors were forced to become actors recalling their own personal memories of the body. The work also established many of the traits that have since come to define Park’s distinct methodology: the emphasis on corporeal perceptions, the dramatic staging, the use of sound to integrate temporal and spatial elements, and, above all, the immersion of the audience, who must experience, rather than merely observe, the work.

Park continued her evolution as a video artist the following year with her graduation piece, 〈PULSE ROOM〉 (1994). Although closer to a conventional video work than Incubator, 〈PULSE ROOM〉 still incorporated elements of the surrounding space, such that it should be considered as a “video scape.” In the primary video, a foaming mouth recited the phrase “Be still my beating heart” before disintegrating into static. Another video showed a quivering blue line, reminiscent of a heart monitor just before the patient flat-lines. In accordance with the title, the room where the videos and light-reflecting castings were shown had a distinct “pulse,” from the installation of TV monitors and monitor-shaped sculpture that flickered at various speeds and reflected light. According to Park, the work was partially inspired by her experience studying abroad, when she realized that the flickering light of the TV reflected on the wall of her room felt like a pulsating being.11 Such environment inevitably coaxes contemplations of the paradoxical mixture of frailty and tenacity in living beings, our inherent feelings of isolation, and the contrast between warm, organic life and cold, inhumane medical systems.

For Park, any information that we acquire through our minds is indirect; the only direct form of knowledge comes via the body. As such, she believes that the sensations and perceptions of the body are the only form of truth.12 This single idea—that no meaning exists outside of primal, physical experiences in the moment—is at the heart of Park’s videos and installations, all of which function by generating palpable and subjective perceptions within each visitor. In 1998 (the year after her return to Korea), Park presented a performance-style work for the 〈Flying Circus Project〉 (a performance workshop organized by the Singapore theater group, Theatreworks), in which she transformed the process of applying and removing makeup into a ritualistic ceremony. Two years later, Park took part in 〈Desdemona〉 (2000-2001), another experimental theater event presented by Theatreworks, for which she collaborated with Asian artists from different fields (e.g., music, dance, theater, and fine arts). For the event, expanding upon her role as an artist, Park also performed and designed the costumes. And as a video artist, Park produced video works within the play that used a female character named Mona to present a humorous take on the irrational circumstances faced by contemporary women.

During the 2000s, Park continued to participate in experimental, multimedia theater performances. One of the most notable examples was 〈Cult–robotics〉 (2004), for which she and fellow artists Hyunsuk Seo and Sungmin Hong each wrote one act on the theme of robots and marriage ceremony.13 Moving beyond the personal to enact a truly collaborative experience, Park and her colleagues presented an open, nonlinear narrative within a deconstructed theatrical space that subverted the focused gaze of traditional theater.14 Mixing dance, music, art, and drama, this “total theater” piece wildly satirized the modern link between marriage and capitalism, with male and female dancers connecting like conjoined twins while numbered lottery balls popped out of a pregnant woman figurine’s groin. Unlike traditional performances, in which the viewers must passively observe what the artists have chosen to show, 〈Cult–robotics〉 presented the audience with an infinite array of spectatorial possibilities, thus ensuring that each person would have a unique subjective experience. This capacity is the primary reason that Hwa Young Park has continuously reached beyond video into theatrical art.

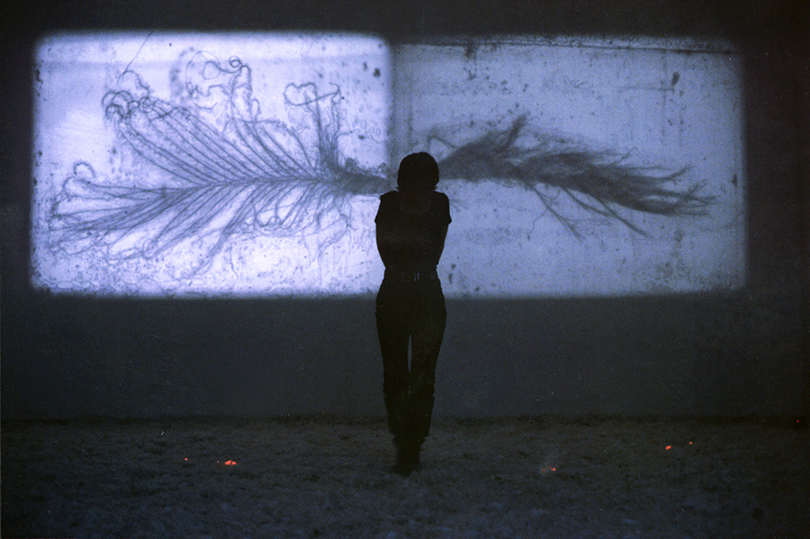

Hwa Young Park, 〈Animate Aviation〉, 1996-1997, film installation including two loops of 16mm film, two 16mm projectors, feathers, lasers, and reflectors.

Hwa Young Park, 〈Blind Square〉, 2004. third act of Cult–robotics.

2.Hwa Young Park’s freedom and flexibility as an artist can be traced directly to her time as a graduate student in the US, when she enjoyed access to audio-visual materials that simply were not available to many of her colleagues in Korea. From 1992 to 1994, she studied video production at the Pratt Institute in New York. Significantly, she chose to specialize in “New Forms,” which further encouraged her to ignore the conventional boundaries of genre.

While in the US, Park also completed a program in 16mm film production at New York University. Even so—and despite her professed love of cinema—she has worked almost exclusively in video, rather than film, after her return to Seoul. Her preference for video is based on both practical and personal reasons. To begin with, 16mm film was (and still is) much more expensive and difficult to access than video. But perhaps more importantly, film production generally involves working with a large cast and crew, which does not seem to suit Park’s artistic vision. As personal computers and digital cameras (especially 6mm DV camcorders) became widely available, Park was able to work independently, pursuing her own expressions of film, video, theater, and art.

Aside from her graduation piece for the film production workshop, Park’s only work to use 16mm film is 〈Animate Aviation〉 (1996), which she produced during her PS1 residency. Shown on two projectors with actual feathers attached to the clear leader film stock, this work recalls the experimental films of artists like Stan Brakhage, who burned or drew on celluloid film as a way of underscoring its material qualities. Even here, however, Park’s approach is more theatrical in its staging, seeking to enhance the emotional experience by stimulating the viewer’s senses, rather than exploring film medium structurally. As visitors entered the installation through a narrow corridor, the increasing sound and position of a light bulb evoked a heightened sense of ascension. They eventually emerged into an open space, where they were faced with a huge image of a fluttering feather, generated by the feather that was looping on the projector behind them. Scattered across the floor were more feathers, which would be illuminated in red when kicked by visitors, due to lasers strategically placed at ankle level. Embodying weakness and vulnerability, the feathers symbolize sympathy and compassion for all living beings, who perpetually seek to overcome their fleeting, frail existence with dreams transcendence.15

If 〈Animate Aviation〉 shows the influence of film in terms of form, then 〈Jaywalker〉 (1998) represents Park’s exploration of cinematic narrative in terms of content. Adopting the general format of a film essay, 〈Jaywalker〉 is a quasi-documentary about a stray dog that Park observed for a year around a local apartment complex, depicting the communion between two separate beings who share the pain of solitary individual existence. Recalling Chris Marker’s 〈La Jetée〉 (1962), the piece consists entirely of still images (i.e., photographs and drawings), accompanied by voiceover narration of an internal monologue. However, the formal similarity to Marker’s film is more of a coincidence than an homage. Faced with the difficult task of documenting a wary animal that would dart away at the first sight of people, Park had no choice but to resort to an automatic film camera with autofocus, rather than a camcorder or manual camera. To create the final piece, the artist first recorded the entire narration, and then filmed the still images with a Hi8mm camcorder, switching them out according to the time code of the narration. Because analog camcorders produce some noise whenever recording is stopped, Park had to meticulously plan the filming process so that each shot could be filmed in a single take. This involved carefully placing each photo in a precise position, without altering the lighting, focus, or position of the camera.16 Like 〈La Jetée〉, the camera occasionally pans and zooms on still photographs in 〈Jaywalker〉, but Park asserted that these movements were actually inspired by the filming of old black-and-white photographs in history documentaries.

What began as a simple record of a stray dog evolved into a personal diary blending fantasy with reality. Although quite distinct from a conventional documentary, Jaywalker still contains the most linear narrative of any Hwa Young Park’s work. Indeed, Park’s subsequent video works became increasingly non-linear over time. Even a single-channel work such as 〈Itch〉 (1999)—in which Park used the motif of roadkill to evoke the “itchiness” of a troubled conscience and the conspiracy of silence in an irrational world—leaps from one image to the next with no apparent motivation, other than metonymic adjacency. But the non-linear and multi-layered aspects of Park’s works became even more pronounced in her multi-channel videos from the early 2000s, with their intercutting between channels. In 〈Everything Okay?〉 (2003), for example, the respective channels were projected onto opposing walls, making it impossible to view them simultaneously. Black-and-white images of a woman picking up pieces of some useless object were juxtaposed with a color video of an abandoned fragment dreaming of itself as a whole. The contrast between the channels highlighted the odd covalence between reality and dream, which coexist like two sides of a coin. Park used a similar approach in her four-channel video work 〈Drive〉 (2003), another blend between documentary and fiction in which four intersecting stories are linked by an abandoned piano.17 Emphasizing the presence of the abandoned and “useless,” the images, sounds, and narrative of each channel converge and diverge like the melodies of different instruments within an orchestra.18

Hwa Young Park explained that her nonlinear multi-layered narratives are intended to “suggest possibilities for communion within the cracks of a given system, beyond communication with the language that we have been acquired.”19 But how were these unconventional, even difficult works initially received in Korea? Around the late 1990s, when Park returned from the US, there was a push for multi-disciplinary, “New Media” works within the Korean art field, often with government support. Since commercial galleries had yet to emerge as active forces, market influences were less of a factor at the time. These conditions created an atmosphere of experimentation with artistic forms and genres, as exemplified by exhibitions such as 〈The Cross〉 (1999)20, wherein video works were screened at movie theaters and the catalogue was produced in the form of a VHS tape, and 〈Fall Fall Fall〉 (1998), in which Park, Seo Hyun-suk, and Sungmin Hong told the story of a love triangle through interwoven narratives relayed from the different perspectives of the three participants. In such environment, Park’s multimedia experiments were applauded for their fresh and forward-thinking sensibility, even if critics and audiences did not yet fully understand them. Given that single-channel videos had only just begun to emerge as a viable format, the Korean art world was not yet equipped to process the complex structure and non-linear narratives across channels and genres.21 Furthermore, the rapid overall expansion of the Korean art world precluded many from taking the time to scrutinize the texture of works with such abstruse and introverted content.

Marginalized by the escalating competition of spectacle, Park had to wait patiently for people to apprehend what she may have called the “great flapping that a single abandoned feather dreams of.”22 In Korea, it is not unusual for complex and subtle artworks to be overlooked in favor of brash, self-evident works with a clear message, even within a temporal format such as video art, which generally requires special effort for appreciation. The feature of Korean video art scene depends on not only artists who have focused solely on crafting their own subjective language, but also audience’s preference which has influenced the atmosphere of scene by choice. In fact, a compelling argument could be made that the feedback loop between the audience and the artists has been one of the defining factors in the history of Korean video art.

Hwa Young Park, 〈Everything Okay?〉, 2002-2003. two-channel video (5:30).

Hwa Young Park, 〈Drive〉, 2003. four-channel video/eight-channel audio (11:00).

1 The other featured artists were Kim Young-jin, Bae Bien-u, and Lim Young-sun.

2 After being held in 1997 at New York’s Exit Art/The First World, this exhibition was staged again in 1998 at the Ilmin Museum of Art in Seoul. (Curator: Kim Yu-yeon; participating artists: Lee Seung-taek, Lim Choong-sup, Yook Tae-jin, Lim Young-sun, Yoon Dong-chun, Hwa Young Park, Kim Myung-hye, Sungmin Hong, Kim Young-jin, and Cho Sook-jin.)

3 Supervising curator: Lee Won-gon; 41 participating artists including Hwa Young Park, Shim Cheol-woong, Kong Sung-hun, Park Hyun-ki, Kim Hae-min, Ken Feingold, Toshio Iwai, Nam June Paik, Kim Se-jin, Oh Kyung-hwa, Lim Young-kyun, Lee Kang-woo, Lee Ju-yong, and Min Byung-hun.

4 Out of 157 applicants, the following ten artists were selected: Kwon So-jin, Ryu Ji-seon, Park Ji-hyun, Hwa Young Park, Ahn Seung-min, Oh Jin-young, Jeong Ra-mi, Jeong Ju-yeong, Cho Seong-hye, and Choi So-yeon. A total of KRW 10 million in production costs was distributed among the ten finalists.

5 Author’s interview with Hwa Young Park, February 16, 2019.

6 Ibid.

7 Interview of Hwa Young Park by Chae Mi-ji, “To the Many Small Cubas of the World Pursuing Their Own Revolutions,” Yukgam Masaji (Six-Sense Massage, ed. Ryu Byung-hak), Nabi Press, 2011, p. 141.

8 Chae, ibid, p. 140.

9 Interview, February 16, 2019..

10 Chae, ibid, 140.

11 Chae, ibid.

12 Chae, ibid.

13 Another representational example was ROK-A-BA-EE (2005), a multimedia performance on the theme of Samuel Beckett organized by the Japan Foundation Forum.

14 Cult-robotics pamphlet (no page number).

15 Because 16mm projectors is difficult to handle as a fire hazard, the actual 16mm film was shown only once, before being replaced by a corresponding video.

16 Interview, February 16, 2019..

17 D shows the piano being cleaned and dusted; r is a story told from the perspective of someone who finds the abandoned piano; i concerns the sounds produced as the disassembled piano is loaded into a car; and ve is a fictional story inspired by odd items found inside the piano.

18 Chae, ibid, p. 145.

19 Chae, ibid, p. 146.

20 Curators: Sejin Kim and Lim Yeon-sook; participating artists: Kang Young-min, Kang Hong-goo, Sejin Kim, Park Eun-young, Park Il-hyun, Hwa Young Park, Lee DonGi, Lee Jung-jae, and Sungmin Hong.

21 Demonstrating the overall unfamiliarity with video art at the time, one article from 1998 suggested that video artworks should be shown within a separate type of installation, such as a black box, that is contrary to today’s common notion of video installation in gallery characterized by variability of format and mobility of the viewer. Kim Hyeon-do, “The Path Forward for Korean Video Art,” Art Monthly, Oct. 1998, p. 80.

22 Author’s interview with Hwa Young Park, February 16, 2019.

Hye Jin Mun / Art Theory

Hye Jin Mun is a critic, translator and lecturer at Korea National University of Arts. Her major interest is technology-based media and cross-media study in contemporary art.