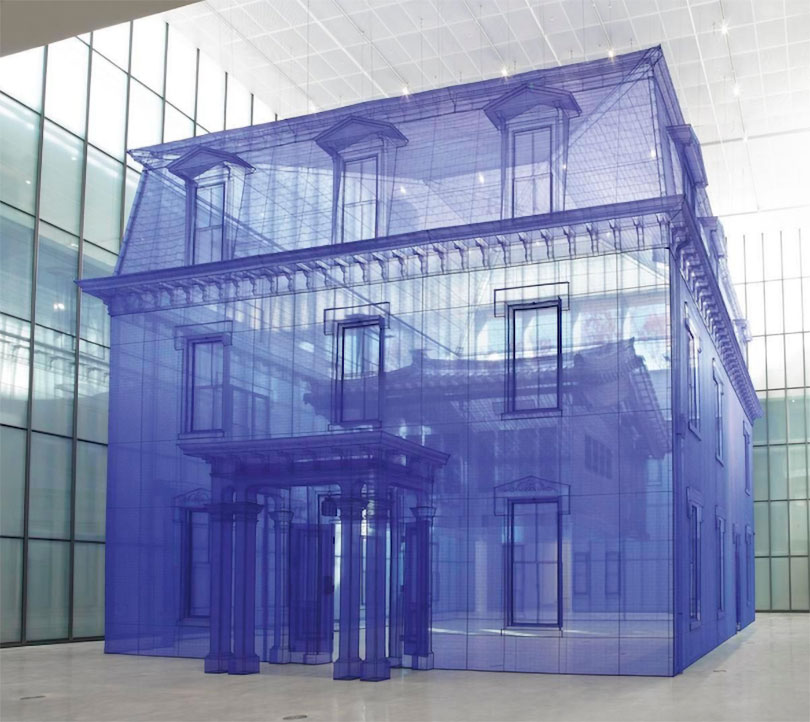

Do Ho Suh, 〈Robin Hood Gardens〉, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG, 2018. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

When Do Ho Suh broke onto the New York art scene in the late-1990s, you could tell a star was born. A graduate of Seoul National University, Rhode Island School of Design and Yale University, Suh mines the traditions of his Korean heritage while reflecting on his personal experiences. His sculptures and large-scale installations present the uniforms he has worn in life, the homes where he has lived, and people from all walks of life coming together to create a unified force.

The artist represented Korea at the 2001 Venice Biennale, has had more than 60 solo museum and gallery exhibitions worldwide, has participated in multiple biennials and important group exhibitions and has work in the collections of major museums internationally.

I first discovered Suh’s compelling work in his very first New York exhibition, a group show titled 《Techno / Seduction》, at The Cooper Union in 1997 and first wrote about it for Artnet when he was in the Public Art Fund exhibition 《Beyond the Monument》 at MetroTech Center Commons in Brooklyn the following year.

The piece at The Cooper Union was 〈Who Am We?〉, which is an installation of wallpaper made from thousands of photos of teenage faces taken from high school yearbooks. Printed as tiny portraits in a grid format, the piece blurs the boundary between the individual and the masses. Still one the artist’s favorite artworks, he later said of 〈Who Am We?〉: “In the title I wanted to underline the distinction between singular and plural. In the Korean language, there is no such distinction."

Do Ho Suh, 〈Public Figures〉, 1999. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

When discussing his sculpture 〈Public Figures〉, which presents an empty pedestal supported by a crowd of people, I wrote, “Suh turns the traditional monument upside down by presenting a large white pedestal supported by a procession of several hundred miniature bronze figures. The heroic here is not to be found embodied in a statue above, but with the masses below.”

These two pieces were my first connection to Do Ho Suh’s work, which continues to resonate with me to this day. His work has been described as confronting questions of home, physical space, displacement, memory, individuality and collectivity, but for me it’s mostly about connections, or as Suh might say “karma.”

When I asked him about the exploration of karma in his work in a 2008 interview for Artkrush, which I was editing at the time, Suh said, “It's an organic way to explore the boundaries of this notion of individualism, in which each individual is the accumulation of so many different and discrete things. It's then that the accumulation of so many different and discrete individuals creates a bigger group, a bigger country and a bigger world.”

I saw this connectivity at play again in Suh’s first New York solo exhibition at Lehmann Maupin in Soho in 2000, where he exhibited 〈Floor〉, a sculptural installation featuring 180,000 small plastic figures of both sexes and different races supporting a glass floor that viewers could walk across, and in his massive sculptural figure 〈Some/One〉, which could be interpreted as a warrior in a ghostly suit of armor or a spiritual presence in a ceremonial robe, that he strikingly assembled from one hundred thousand stainless steel dog tags and exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris in 2001. Approached from behind, it holds a mirror in its interior so that the viewer sees him or her self reflected within.

Do Ho Suh, 〈Paratrooper-I〉, 2003. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

And karma was at the core of the next work of Suh’s that I reviewed for the Italian art publication Tema Celeste, 〈Paratrooper-I〉, which he presented at Lehmann Maupin in Chelsea in 2003. Of it, I wrote: “〈Paratrooper-I〉 is a metaphoric self-portrait. A small stainless-steel paratrooper stands atop a concrete pedestal pulling in a deflated parachute. The long pink threads he tugs upon are connected to 3,000 signatures—including New York Times critic Roberta Smith and Whitney Museum curator Donna DeSalvo—that have been collected from personal journals and exhibition guest books, and then hand-stitched onto a linen chute that is suspended on the wall in an oval form.

“The lines do not touch each other until they are forcefully pulled through the paratrooper's hands, yet together they loosely form a singular cone of vibrant color, magically occupying space. On the opposite wall, Suh hung three small works on paper, rendered in the same simple style that he used when he first left home years ago. Using the color red to represent karma, he shows a man being blinded by the hands of a child perched on his shoulders in one work, and a muscular figure juggling the threads of life in another. The third drawing reveals a soldier falling from the sky with a multicolor parachute made from numerous shirts or uniform jackets. With an interest in ‘intangible, metaphorical and psychological’ space, Suh's work is perhaps reflective of his own experiences. Dropped into a new terrain, Suh recognizes that he could not have survived without the support of countless others, and he remains eternally bound to this evolving history.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈Myselves〉, 2015. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

This is a theme that the artist has continued to explore in a variety of media—combining the opportunity to investigate it anew while continuously experimenting with innovative forms of creativity. We see that in such sculptural installations as 〈Cause & Effect〉, 〈Karma〉 and 〈Net-Work〉 and drawings like 〈Whispers〉, 〈Karma Juggler〉 and 〈Myselves〉. And when I saw one of Suh’s films for the first time in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Pavilion of Applied Arts at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, it sparked my interest as to how he got from sculpture to film and made me wonder if there was linkage, which I have since discovered.

All of the works that I have just mentioned strongly illustrate this idea of connectivity or karma, but this interest wasn’t as apparent to me in Suh’s more famous house sculptures and drawings until I saw his first film, which came before the Venice project. But more about the films later. I now want to discuss the importance of the house pieces to his overall body of work.

When I saw his first home sculpture suspended in a gallery at MoMA PS1 in the Greater New York show in 2000 I thought it was curious but knew little of what it was about—beyond some kind of memory of his homeland.

Do Ho Suh, 〈Seoul Home/L.A. Home〉, 1999. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

A recreation of his childhood home—a traditional Hanok house that his father, the painter Suh Se Ok, designed and built, 〈Seoul Home/L.A. Home〉 (as he called it because it had initially been exhibited in Los Angeles) was made from green silk organza, which Suh had sewn together with the help of a seamstress and assistants in Korea.

“The first Korean house, which was a replica of my family house in fabric, was probably about longing,” Suh told me in the Artkrush interview. “It had to do with displacement—when you’re physically and psychologically displaced, longing develops, and you carry it with you constantly. I visualized it in the space of personal memory and history, but the piece transcends personal history because the original house was built in a traditional style of Korean architecture. When it was shown in the Greater New York show, it floated above the crowd like something gently falling from the sky. Its translucency and the lightness made it seem like the ghost of a home. It was my home, but at the same time, it became everybody’s home.”

“Like 〈Paratrooper-1〉, the house allowed me to land softly and safely in this foreign country. The parachute, the house—they're both spaces that protect you. Then there are the strings of in yeon—lifelines of people and their love, their help, their thoughts of you—that connect you to those spaces.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈Seoul Home/L.A. Home〉, 1999. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

He made it in silk so that it could be folded up and carried with him so that he could be at home wherever he went. He’s talked about a saying in Korea of walking your house to a new location when you take a traditional house apart and rebuild it someplace else and has expressed that concept in his drawings. But he has also talked about being haunted by this particular house and even having a sense of displacement when he was growing up in it.

“In many ways it’s kind of an unreal building,’ Suh has said about the home, where his parents still live. “It’s an odd house in which to live in the 21st century. It was like living in a time capsule—it was a very idealized house right from the beginning. That’s the kind of sense of displacement I had every time I went out of the gate to go to school. I was living in a secret garden.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈The Perfect Home II〉, 2003. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

So even though Suh’s sense of displacement is most often discussed in relationship to his moving to Providence, RI to go to school at RISD, his relocating just brought it to the surface, where he turned it into subject matter for his art. He famously took the concept further in his sculpture 〈The Perfect Home II〉, which was initially shown at Lehmann Maupin in 2003 and was more recently on view at Brooklyn Museum.

A full-scale re-creation of the artist’s former apartment in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City, the sculpture meticulously reconstructs the space in translucent nylon. Presenting his 400-square-foot apartment along with the adjoining corridor and staircase to his landlord’s living space above, it was detailed right down to doorknobs, light switches, radiators, kitchen appliances and the bathroom fixtures. Painstakingly recreated by making measurements of the architecture and everything in it, it became the next chapter—following his Korean home—in an ongoing project of documenting the places that have touched the artist’s life.

Do Ho Suh, 〈Fallen Star 1/5〉, 2008. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

His 2008 sculpture 〈Fallen Star 1/5〉, which recreates the building he inhabited in Providence being struck by his falling Korean home, looks like a beautifully fabricated doll house. When I asked him about it shortly after it had been made he said, “I wrote a story about the journey of a Korean house that was lifted by a tornado, flew over the Pacific Ocean, and landed in Providence, Rhode Island, where I was going to school. But the house didn’t just drop from the sky—it had a parachute. When the house started to descend, the chute opened so it didn't totally crash; it came down slowly, hit the corner of the Providence building, and got stuck. It’s not a “boom,” but a delayed impact.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈Home within Home within Home within Home within Home〉, 2013 © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

He employed the three-story Providence house again in his 2013 sculptural installation 〈Home within Home within Home within Home within Home〉, but this time at full scale in blue polyester fabric. In the middle of it he hung another version of his Korean home, as though it had been completely swallowed by his new existence. And he gave new life to the story of the Korean house crashing into his Western life when he created Bridging Home, which finds the Korean house lodged between two British buildings, for the 2010 Liverpool Biennial and his amazing 2012 commissioned project 〈Fallen Star〉, which perched a house—complete with furnishings and a garden—atop a building on the campus of the University of California San Diego.

Do Ho Suh, 〈Fallen Star〉, 2012. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

His New York apartment and other spaces where he has lived have become the subject of other types of projects, such as the rubbings he made of the Chelsea flat, thread drawings that reproduce aspects of the abodes, and flattened details and 3D objects from his personal spaces.

Regarding the objects Suh has stated, “The most important process is to measure these things really thoroughly. For instance, a refrigerator, you open and close it numerous times a day so you would think that you’re very familiar with it. But once you start to measure it, it’s a totally different story. You begin to understand how the object is made. By measuring, you consume the object in a different way.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈Specimen Series 348 West 22nd Street, APT. New York, NY 10011, USA.〉 © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

Long interested in architecture—his younger brother, whom he has collaborated with on projects, is a practicing architect—Suh has combined his residences to fabricate new structures and turned his past homes into architectural interventions by creating site-specific projects that engage existing space. Perhaps that’s why he was commissioned by the V&A to make a film about an architectural landmark. But before he could do that he had to prove—at least to himself—that he could work in film.

Do Ho Suh, Gate Installation view, Luminous The Art of Asia Seattle Art Museum, 2011. Photo by Nathaniel Willson. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

His first foray into film came through his 2011 sculpture and video installation 〈Gate〉, which was was presented as a contemporary introduction to the Seattle Art Museum’s historical collection of Asian Art. For it, Suh used one of his existing fabric pieces and created an animated video drawn from the objects and projected it onto the piece.

His first film to use real-life footage that he shot was the 2015 short 〈Passage/s: The Pram Project〉, which was presented as a three-channel video installation at his London gallery Victoria Miro and Lehmann Maupin Hong Kong in 2017. Capturing Suh and his young daughters strolling the streets of their London neighborhood, the footage was shot on GoPro cameras attached to the sides and top of the stroller, or what the British call a pram. Presenting a child’s view of the city, the film is interspersed with imagery from Seoul as the children shift between speaking English and Korean.

In discussing the film Suh recently shared: “I was completely new to London, and my daughter was born. And by pushing her pram, we both started to explore and learn the neighborhood at the same time. I have experienced London in a different way than I did in New York. New York was right after grad school, where my career started and I was in my 30s. It was a different time and place. But London is for family, so I see the space in a different way, and also through the eyes of my children.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈Passage/s: The Pram Project〉, 2015, Installation view at Victoria Miro, London, 2017. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

This statement is what brought me back to connectivity and the idea of karma and made me understand how the home pieces and the films are linked to this concept through family, through continuity. At Victoria Miro the film installation was shown at the end of a connected architectural installation that was made up of linked passageways from different places where Suh has passed his life, a life that he is now preparing to pass on to his children. And in the course of my research I found another quote from Suh about the pram film that made me realize that I was on the right path.

“My children are a great inspiration,” he said. “Before, everything was about two generations—my parents and me. Now there are three generations. I’m inspired by being a father. But maybe it’s not so different. Fatherhood, childhood, karma, home—it’s all connected.”

His film for the V&A’s Venice Biennale exhibition 《Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in Reverse》 was just as experimental but less subjective in content. Titled 〈Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG〉, the jumbo, dual-channel video installation pans the utopian London public housing development Robin Hood Gardens, which was designed by architects Alison and Peter Smithson in the late 1960s and completed in 1972.

Do Ho Suh, 〈Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG〉, 2018. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

Suh was commissioned to make a film about the housing project as one of the buildings was being demolished and the residents of the other building watched and awaited their eventual displacement and home’s demise. Using time-lapse photography, drone footage, 3D scanning and photogrammetry, he moves the viewer from the outside of the building to the terraces and interiors while panning up and down and side to side. We’re able to marvel at the Brutalist design and materiality of the building while also seeing its wear and tear.

We’re taken inside apartments that are still inhabited as the camera seems to seamlessly move right through the floors to give a sense of the variety of ethnic backgrounds and living styles of the inhabitants. But most importantly, we see that the apartments in the building are peoples’ homes—homes that they are about to lose. Shots of the building that was being razed show the shells of the exposed apartments with the outer skin of the building ripped away, as though it had been surgically removed.

A meditation on architecture and living, the final scenes show residents sitting in their homes and then one by one getting up to walk away. Fading as they vanish from the homes, the camera continues to pan up to the roof of the building, where London’s skyline of tall buildings is seen in the distance before the film fades to black.

Speaking about the interest of the V&A, which has preserved part of the building, in the project to a journalist, Suh said, “They see spaces as an architect would, that is, as a physical entity, a hard shell. For me it’s the intangible quality—energy, history, life and memory that has accumulated there.”

Do Ho Suh, 〈Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG〉, 2018. © the artist. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

He purposely used time-lapse photography and took hundreds of shots and then stitched the imagery together to create a slow and steady movement through the structure. “You could get the same effect with a video camera in 10 seconds,” he’s said. “But because it takes 30 minutes, it reflects the lengthy experience of the residents, some of whom had lived there for 25 years.”

After spending a lifetime thinking about the spaces that he has inhabited, Suh revealed that he’s able to poetically convey what home means to all of us—a connection to history, memory and life.

※ Click to Read the Original Article on Whitehot Magazine: Do Ho Suh: From Sculpture to Film

※ This article was originally published in Whitehot Magazine on NOV 2019 by Paul Laster and reposted by kind permission. Copyright © All rights reserved by the author and Whitehot Magazine.

Paul Laster

Paul Laster is a writer, editor, independent curator, artist and lecturer. He is a New York desk editor at ArtAsiaPacific and a contributing editor at Whitehot and artBahrain. He was the founding editor of Artkrush.com and Artspace.com and art editor of Flavorpill.com and Russell Simmons's OneWorld Magazine; started TheDailyBeast.com's art section; and worked as a photojournalist for Artnet.com and Art in America. He is a frequent contributor to Time Out New York, New York Observer, Modern Painters, ArtPulse and ArtInfo.com.