People / Critic

Seeun Kim: Living with the Absence of First Nature, Living among Second Nature

posted 17 Mar 2021

The fact that something is being painted implies that the subject being painted is receiving attention, and the fact that something is receiving attention points to its validity as something worth being known or told. The outcome—what’s painted—of this process is placed in an inescapable relationship with history as an index. That is to say, painting has always been a practice dedicated to grasping reality, an act of producing evidence indicative of a certain time, an allegorical action demanding of interpretation. An act of visualizing or putting a sharp edge around something cannot help but be appropriated and contextualized upon the terrain of reality that enabled such an act. The ontology of this seismometer of history, or painting (art) as an unconscious, automatic apparatus that sublates the world, is grounded in this very terrain. Then how does Seeun Kim’s work preserve the world of today? In what way does she sublate the world in order to formalize it? That is, how does she imprint reality onto her work?

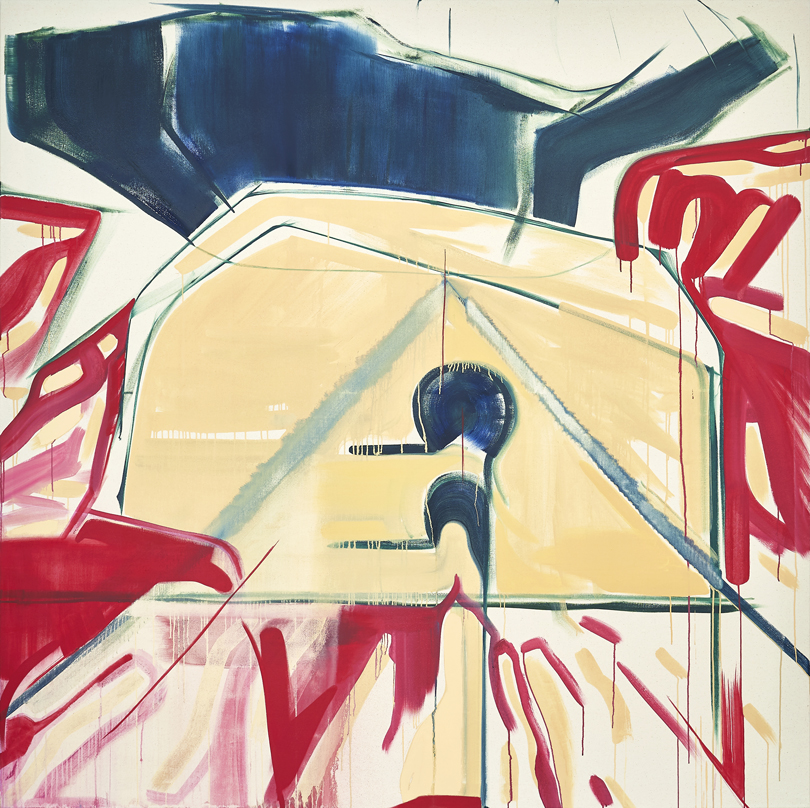

〈Hubble Bobble〉, 2020, water mixable oil on canvas, 190 x 200 x 3 cm. Image provided by MMCA Residency Goyang

To answer these questions, we must observe both the continuity and discontinuity by way of which she traveled through the time between the official beginning of her career and now. As can be seen in 〈Park-Blueprinted〉 (2013) depicting a roadway cut across a park, 〈Isle〉 (2014) capturing a basin in the middle of a stream flowing across a city, and 〈Nearly Forest〉 (2015) focusing on the view that overlooks roads cut across a green area, the artist has been inquisitive of artificial nature, i.e., evidence of first nature found in second nature. Works produced around this time convey a pseudo-landscape of sorts, or more accurately, the impossibility of landscape in itself, because the appearances of nature she paints are already overly mediated by humanized cultural spaces. Simply put, the natural aspects that appear in her works are destined to point to the artificial environment in one way or another as does the paved road nonchalantly traversing the upper portion of the green land in the foreground of 〈Facade of the Woods〉.

As pointed out by Kenneth Clark early in time, historical landscapes produced post-Flemish paintings marked the stature of nature as no longer accessible to humans, illustrating the irrevocable separation between nature and culture.1) It is almost as if the precondition of a “landscape” at the time was the very ability of modernity to reorganize the modern space that is second nature. In Kim’s work, however, a landscape is something so integrated with second nature that it has lost its intuitable objecthood—the kind projected by something placed outside of the human body—and failed to even function as an aesthetic “outside.” The landscape in this sense is the kind that cannot stand in for some lost substance, is incapable of evoking nostalgia, and is too up close to be gazed upon. In this respect, Kim’s works from around 2015 largely present themselves as allegories for post-landscape landscape. What they signify—or what aspect of humanized nature they direct attention to —is none other than the postmodern condition of life, which has intensified to a point where environmental regulations and landscaping businesses define our system of daily life. It is not surprising that this condition is associated with the notion that “there is no outside world,” a notion that has embraced the entire surface of the earth into the realm of culture. The imagery the artist ultimately aims for is something in the vicinity of the stature of nature in the contemporary world or the impossibility of first nature.

Kim’s works, which as such have been variations of an archetype and an extension of the post-landscape genealogy, see a sort of a tendential leap or discontinuity roughly around 2016. What is worth mentioning about this period is the shift from figurative to abstract, or a pivot from figuration to figurative abstraction, which also coincides with the change in her subject matter. For the first time in 2016, she diverts her focus from evidence of nature found in the city (or “leftover spaces” as she would call them), dragging the axis of her work closer toward the heart of the city. For example, works like 〈Crack〉 (2016) and 〈Leftover〉 (2017) obviously capture parts of facilities that serve a purpose in the city, but it’s ambiguous as to what the larger subjects are because the forms are distorted almost to the degree of abstraction. As also demonstrated by works such as 〈Division of Isles〉 (2017), 〈An Eye〉 (2018), 〈Grab and Run〉 (2019), 〈Inactivate〉 (2019), and 〈Hubble Bobble〉 (2020) each depicting an idle parking lot, a tunnel, a passageway to a station, a construction site, and a lower section of an overpass, her attention is largely directed toward the retrorse aspects of the so-called “abstracted (modern) spaces.”

〈Hubble Bobble〉, 2020, water mixable oil on canvas, 190 x 200 x 3 cm. Image provided by MMCA Residency Goyang

The subjects of her newfound interest circa 2016 were, so to speak, spaces symbolic of forged experiences of modern temporality, more specifically, the cracks in the hardly detected spaces or the compositional exterior, the weak links. And here, we recognize foremost the “discontinuity” as mentioned above—Kim’s imagery turning from “second nature’s mediation of the first” to “fissures in second nature itself.” This, to quickly visit Freud’s schema, seems close to a sort of reaction formation (defense mechanism), because whereas the impossibility of first nature as a result of second nature’s intervention points to the absence of an outside world, the fissures in second nature point to the possibility of an inner outside world. In this case, the discontinuity in the context of her work would signal an attempt to find a room for possibility, an attempt to sail across the sense of despair stemming from her early imageries. For example, the cracks, niches, holes, fissures, and tunnels constantly explored in these works can be read as allegories for an outward portal that transcends the existing urban premise or as allegorical practices seeking to gaze at the possible exterior of the city or modernity. In that sense, the fact that the subject of her interest shifted from the “range of relationships among the roads, trees, and buildings”2) as shown in her earlier works to the power, effect, and causality of the city’s functional parts as shown in her later works is neither arbitrary nor perceivable as a coincidence.

On the other hand, what’s key about the tendencies shown in her later works is why the parts of the city had to be presented in such a near-abstract manner and form. What sort of validity does abstraction of figurative subjects hold in today’s painting scene in which even abstract expressionism, which fast-deviated from early abstract painting preservative of hints of figuration, has entered a state of blackout with dust collecting on its top? This is exactly the point from which Kim’s works penetrate reality. To be able to wholesomely portray the contemporary city as a subject, the artist has to capture the transempirical order and the sensory field of the city to begin with, for to portray a city is inevitably the kind of task that requires abstraction. With that said, it seems that Kim understands the fact that if she seeks to portray subjects that operate abstractly on a fundamental level, then such phenomenal forms have but to go through abstraction even if on the most particular level. Her works strive to reach the realm of abstraction operating underneath certain parts of the city that are richer and plainer than ever on the surface.

This type of methodology is also the soundest expression of hysteric sublimeness or the dominant contemporary perception. Inside its own environment, the principal agent that is the fast-paced postmodern city, fragmentized and finely sectioned to the degree of unrepresentable, becomes unable to secure its own meaning, sensing the outside world as some unabsorbable impact. Here, amidst the principal agent’s presentational attempts, figurative objects consequently transform into something abstract. Beaconing the fact that in the contemporary environment, an empirical subject can no longer be fully represented through a realistic attitude—here lies the reason this type of “figurative abstraction” is the most practical and valid method of depicting today’s city.

As elaborated, the foremost thing to pay attention to in Kim’s work is the turn from figuration to figurative abstraction, from second nature’s mediation to its inner division. The coherence that manages to run through the “discontinuity” alludes to the continuity underlying the artist’s works—one affirmative of the stature of second nature. In other words, the continuity in her work comes from the plain narrative that to Kim, first nature is close to something that appears in the form of projections only after a division has occurred in second nature. Her works tell us that there is no such thing as a singular world that humans have fundamentally lost and that there has never been a place to return to. Through the reality achieved via abstraction, she looks directly into the hysteric sublime. Perhaps the essence of her work lies somewhere in between “living in the reality that shapes the sublime” and “keeping an eye on the senses potentially existing outside of that reality,” requesting that the viewers paradoxically attempt to identify the actual places and subjects from the abstracted representations, that is, to figurate and understand the infigurable and incomprehensible.

1)Clark, Kenneth, Landscape into Art (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 121–127.

2)Kang, Seongeun, Seeun Kim, and Even the Neck, roundtable discussion, The Familiar Forest exhibition catalog (Seoul: Gallery 175, 2015).

※ This content was first published in 『2020 MMCA Residency Goyang: A Collection of Critical Reviews』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Goyang Residency

Jeong-Gangsan

As an independent researcher, he has developed works that relate such areas of study as art, politics, society and economy within the context of the capitalist mode of production. His articles were published in 『Art in Culture』, 『Public Art』, 『Misulsegye』, 『The Radical Review』, 『Ob.Scene』. He is currently working as a member of Political Economy Institute Pnyx and Marxcommunnale.