Ahn So yeon

True Story

She says that everything is a “true story,” but in truth, she is always acting, writing a believable story featuring anonymous characters, or taking out-of-focus snapshots. Because she calls them “true stories,” the evidence and testimonies she presents seem somewhat suspicious. Nevertheless, she reiterates that they are true stories, referring to a series of unbelievable events occurring in implausible situations. The phrase true story might be used to describe an event that “seems to be made up” but actually took place, or an event that really took place but had little to no exposure, so that people do not know that it actually happened. In both cases, the events actually take place, but they circle the edge of reality and recall events and beings that are hardly noticed. If there is such a thing, what could it be? Min Sun Lee quietly places art in that space, which seems blank, and suggests that we think.

Min Sun Lee’s recent works have been composed of a central video performance and related text and spatial installations. My first encounter with Lee’s work was at her second solo exhibition, You Know, It Might Actually Happen (2018, Project Space Sarubia). The exhibition, comprising photographs, books, and videos, began with Introduction of Work (2017) and flowed to the three segments of One Day (2017–2018), each occupying a corner of the room and dividing the space naturally. Lee divided specific days (August 11–12, 2017; April 2–3, 2018; June 3–4, 2018) into equal parts to designate moments at which she used her film camera to record spontaneous scenes unfolding in front of her. After printing the photographs, she leaned on the fragmented images to write three short stories, from which she produced three video works. The stories in One Day are about artists D and B, and A, who is “I.” They are all concerned with art.

〈The Ghost Learned from Hearsay That MANDEUK Had Changed his Name〉, 2020, single-channel video, 4 min. 44 sec. Image provided by MMCA Goyang Residency.

Conceived between trivial jokes and serious questions, You Know, It Might Actually Happen explores the universal understanding of the value of and justification for the existence and conduct of the artist, who has been living the life of an artist since 2011. Wrapped in humor, the work demonstrates the artist’s unique way of thinking between the lines. In one video, she introduces her work in a foreign language (English), and in a second video, she describes her daily life and other people in her native language (Korean). Through the perceived difference between the two videos, the artist draws attention to the inevitable gap between art and daily life. (The gap is not only a distance that separates two things, but also a space that mediates a bilateral relationship.) An interesting fact is that most of the events that she claims to have “actually happened” seem fictional, and it is in Min Sun Lee’s pretending to tell the truth while speaking of and describing the event that raises suspicion. What does it mean to pretend to tell the truth?

Nobody Knows

Nobody knows that you are an artist who walks on all fours.

D is an artist who walks on all fours, featured in a story written in August of 2017 as part of One Day. No one knows how he walks on all fours, when he walks on all fours, where he walks on all fours, or why he walks on all fours. “I” seeks D out, caught up in the question of whether art is the reason. D’s walking on all fours rather than on his two feet, a contradiction akin to reading a book written in a foreign language instead of one’s native language, is an act that invites failure and isolation. The unrealistic illusion that D must not be a person is corrected within the relationship among B, C, and E, catalyzing a keen awareness of the presence of D, who acts “nonchalantly” and is “unfazed” by anything. Therefore, D’s nonchalant and unfazed acts are understood by no one. Through such narratives, Min Sun Lee continues to develop storylines in the middle, where the tedium of life and artistic anguish can pause together, and art and artists can be re-recognized as “true stories.” This is where humor comes in.

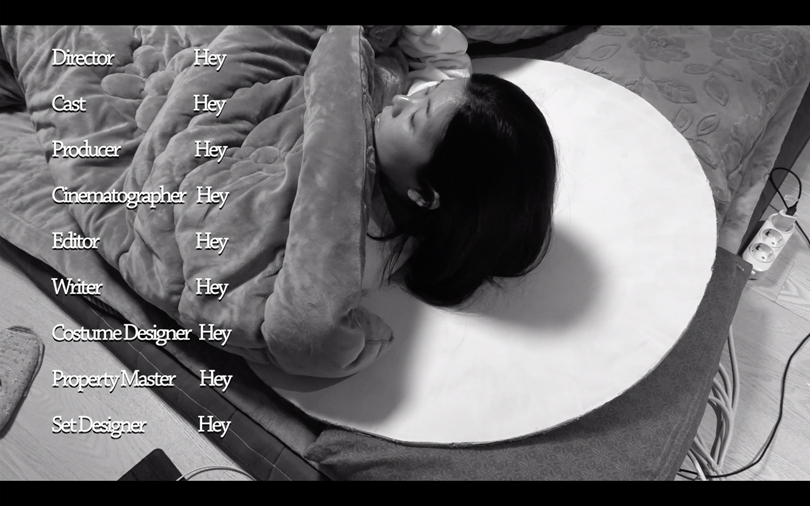

For her third solo exhibition, Desperate Humor (2020), Min Sun Lee referenced a series of jokes that was popular in Korea in the 1990s as a key component of her narrative. Desperate Humor borrows from a series of jokes that is described as “chilly” or “futile” humor, reminding the viewer of the nonchalance with which “hopeless” humor that desperately “risks everything” is released into reality. She also takes into account transformations caused by that nonchalance. The (desperate) joke series from this particular period, such as the “Choi Buram series,” “Sha Wujing series,” “Mandeugi series,” and “Deongdari series” are similar in that it is difficult to discern essential characters, causes and effects, or catchphrases. These jokes remind us that the work of the artist, “I,” who gazes at the ceiling to escape the tedium of reality, is neither simple nor easy. (That being said, I do worry that these words will add weight and seriousness to all the humor that the artist has painstakingly laid out and cause it to sink.)

〈The Ghost Learned from Hearsay That MANDEUK Had Changed his Name.〉, 2020, single-channel video, 4 min. 44 sec. Image provided by MMCA Goyang Residency.

Except for the works displayed in You Know, It Might Actually Happen, I browsed/watched all of her works on her website(https://www.ohhora.org/minsun-lee). Clicking on a title promptly loads a video or a photograph. Though I might be stretching to make a connection, Lee’s performance videos seem on par with the “Choi Buram series” in their futile humor. (Certainly, seeing videos installed in a gallery environment and watching them on a smartphone or a notebook computer screen were very different experiences. However, because I do not have many other experiences to compare to these, I will not discuss this matter here, for fear of making an incomplete argument.) For example, in the 2'39" single channel video Nobody Knows, the camera is fixed and seems to be patiently watching a situation unfold. From the beginning, someone is crying at the edge of a forest. Strictly speaking, crying is heard over scenery that changes very little. The person is unknown. The camera cannot see the person. Eventually, someone walks out of the forest. She seems to have seen something, but she walks on. When the person disappears, the crying stops, and another person stands up from behind the bushes and appears on the screen. She looks at the camera and around her, then runs away off screen. Where her body and actions had been, the forest remains unchanged. She has caused an incident and run away.

About the Work

Lee’s performance art videos show the simple relationship between the actor and performance with no elaboration or excess, like a basic sentence composed only of a subject and a verb. This is not simple and easy to achieve, however, because the performance adheres to the exquisite boundary between “walking” and “all fours.” In other words, straddling the border between art and ordinary life, she must immerse herself desperately in the tedious life in which she has become an artist while acting like an artist. This situation is like the obvious contradiction that Lee wrote about in a story, of having to pretend to be sleeping in order to fall asleep. When I met Lee, she explained her ongoing project to me. It is yet unclear what incident she will cause, but she will play a role and showcase an art performance of walking on all fours as if it were natural. In the tedium of life, it will be remembered as a momentary event that “fills the time that always remains blank no matter how much I stir it up.”

※ This content was first published in 『2020 MMCA Residency Goyang: A Collection of Critical Reviews』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Goyang Residency

Ahn So yeon

Art Critic