Kim Haeju (curator, deputy director of Art Sonje Center)

Most of Eunsae Lee’s paintings include figures. Landscapes and objects appear infrequently, and when they do appear, they are often blurred in the background. While works from before 2015, which were based on incidents reported in the media, revealed specific places and contexts, her later works most prominently reveal characteristics of people. Lee does not portray proportions of the body realistically, favoring to emphasize and enlarge distinct features as in cartoon characters. Lines that form bodies show speed, capturing particular gestures and directional movement. One element that stands out is the eyes. The nose is often inconspicuous or omitted, and the mouth is also understated. When the mouth is clearly visible, it is closed firmly or baring the teeth in an aggressive manner. The first of Lee’s drawing that I encountered was a small drawing titled Burning girl, which I purchased at the Goods event in 2015. The woman’s torso is on fire (or is comprised of fire) and without form, but her round eyes and pupils remain sharp and are coolly looking straight ahead.

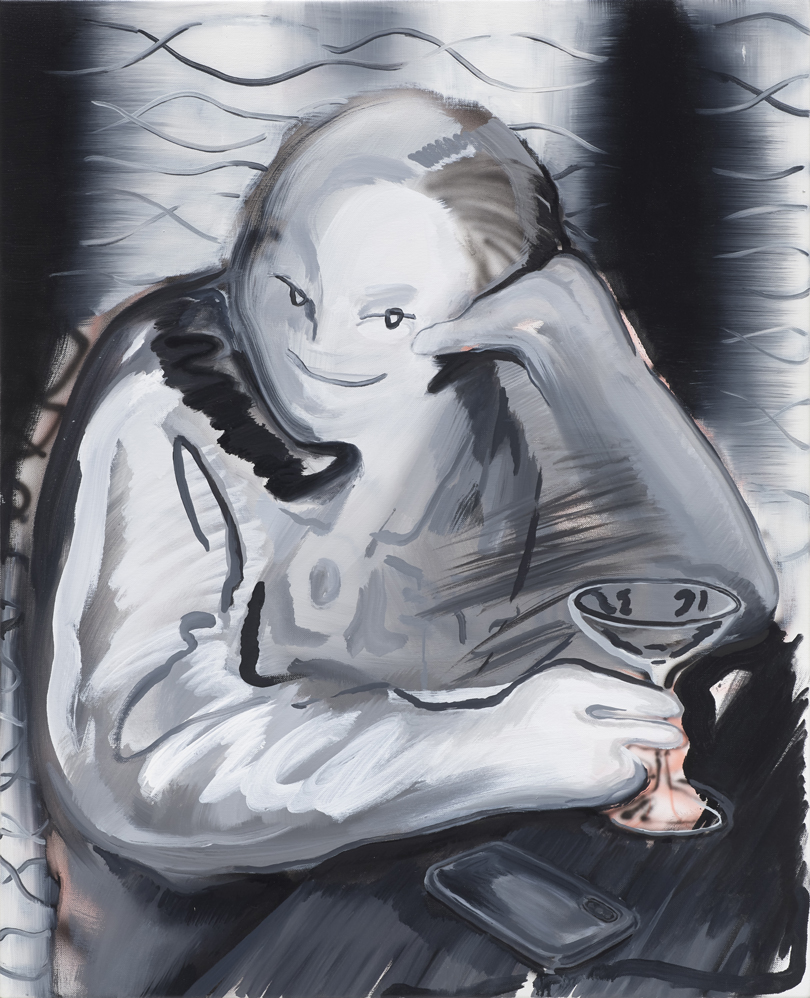

〈As usual at bar〉, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 90.9 x 72.7 cm. Image provided by ArtinCulture.

Another image that I remember by the powerful eyes is from the painting Night Freaks–Pop a Squat (2018). I remember the eyes of the woman who is squatting on the street and urinating. In this painting, details are missing from the face, except for the two luminous points, reminiscent of a cat’s eyes at night, which are directed straight ahead. The two eyes here send a similar message to that of the raised middle fingers in ㅗㅗ (2016). The theme of Staring Eyes (2018) is a recurring one. In this painting, a portion of a face, from the nose to the forehead, fills the canvas. Faint eyebrows and glasses are part of the predominantly green background, against which donut-shaped eyes are shown in a state of tension. In the painting titled Staring Woman, the two circles that make up the eyes look independently alive, and they pop out above the forms and colors of the painting. On-ride camera (2016) shows various forms of gazing eyes. Painted from a photograph of the members of the girl group Girls’ Generation on a Viking Ship ride, the eyes of the eight people in this painting are striking. There is a whole spectrum of eyes, from bored to glaring. Because of the angle of the photograph, the eyes are looking away from the center, but they express the resolve to not be intimidated by whoever is looking at them, the determination to not look at someone the way they are expected to, and the attitude of someone looking at her opponent before a fight. The figures in the works introduced in the exhibition Night Freaks (2018) are mostly looking straight ahead, their gazes directed at the audience outside the canvas. The structure of the painting overturns the power of the gaze, as the figures in the painting gaze back at the person gazing at the painting, and directly engage the viewer in conversation. In a way akin to Bertolt Brecht’s estrangement effect, the painting invites people outside the canvas into the painting, and reinforces their straightforward narrative, which contains complex emotions surrounding provocation and release of anger. Seeing these figures reject the customary gaze toward women, rise above being an object of gaze, speak up powerfully through eyes and poses, and start conversations, I imagined their virtual solidarity with the figures in paintings by the Swiss feminist painter Miriam Cahn, an artist in her seventies who has painted images that expose the complexity of sexual power games and violence through unstable images and scattered details. I thought of Cahn saying, “Anger is a very good motor for art. ”

The eye as a subject that entails the power of the gaze as well as the complex issue of seeing itself. The works in the exhibition Guilty-Image-Colony (2016) explored various contemporary ways of seeing, and questioned, in particular, the ethics of gaze as projected through mass media. Hold a vigil (2016) recalls a scene from the movie Clockwork Orange (1970). In this realistic image, an eye being forced wide open with an eye speculum fills the canvas. The figure in Zero concentration on the bed (2016) is distracted by a smartphone screen, and her eyes have little form, depicted as a simple line under the bright light. The eyes painted at the center of Merged Eyes (2016), too, are gazing at a mobile phone. The composition itself does not directly reveal a negative or critical interpretation of the situation indicated by the title.

〈As usual on the bed〉, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 90.9 x 72.7 cm. Image provided by ArtinCulture.

However, the subjects of Zero concentration on the bed and Hold a vigil urge the viewer to think about forced exposure and contact with images through the media, which occur constantly in daily life, and about subconscious learning through these exposures. In the 2016 exhibition, the artist began her questioning from the act of choosing the object of the gaze and discussing the issue of our gazes being controlled in daily life. In Lee’s 2018 exhibition, her figures looked confidently out of the canvas and toppled the conventional gaze, perhaps bringing her quest to a conclusion.

Lee revisited the theme once again, with works that represent various forms of family structures, for the Young Korean Artists 2019, hosted by the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. In her recent exhibition, As Usual (2020), held at Gallery 2, Lee attempted to switch over to the issue of painting methodology. The exhibition was organized as if showcasing a cross-section of the artist’s repetitive daily exercises. Rather than focusing on a theme or content, Lee explores drawing and painting, and the methodologies of using different media. A portrait with an Instagram filter, food, a cat, a monthly calendar page the artist “X”-ed each day while waiting for the exhibition, and other rather ordinary subjects are showcased. Most of them are achromatic images. The artist states that she goes back and forth between drawing and painting to depict the same subject over and over again. Through this repetitive drawing process, she is questioning what it means for an image to be complete. Considering that Lee deliberately chose these ordinary subjects for her paintings, and that she is using specific color tones and repetitive arrangements, one can infer that this exhibition is displaying more than a methodology of practice.

In one part of the exhibit space are two paintings, Laying with Switch 1 and 2, each on canvases sized 181.8 x 227.3 cm. As the largest paintings on view, they draw the viewer’s attention. One is focused on the expression of lines, and the other is realistically painted. The two monographc paintings have the same composition, demonstrating repetition with a variation of form. The figure is lying on his back with their legs open, holding a game controller, and their eyes display boredom. The enervated eyes, along with the pursed lips, show atonomy, but they lack a strong will and express a complex emotion. The choice of a supine pose and a monochromatic scheme certainly contrasts with the compositions in Lee’s earlier works, which placed figures on colorful grounds and revealed their dynamic qualities.

Therefore, returning to images with the same subject is not an effort to reach a set point of completion, but a difficult process of capturing a vibrating state. Even if you have never said the phrase, “the usual” at a bar, imagining doing so might conjure strange scenes of comfort and fatigue. In this way, repeated images address moments of vibrating emotions in the midst of a dull stretch of time. I thought that the repetition of form, and the vibration felt in the eyes of the figure in the painting, capture an emotion that many people can relate to in 2020. Looking back, I came to think that during the tumultuous recent years, Eunsae Lee’s paintings have captured events as they happened, and the involved emotions of the people observing them.

1)“Miriam Cahn on #metoo, discipline, and why she’ll never stop being angry,” Art Basel, https://www.artbasel.com/stories/meet-the-artists-miriam-cahn.

※ This content was first published in 『2020 MMCA Residency Goyang: A Collection of Critical Reviews』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Goyang Residency

Kim Hae-ju / Independent Curator

Kim Hae-ju is an independent curator. She has worked as a researcher for the National Theater Company of Korea’s academic publishing division and assistant curator at the Nam June Paik Art Center. Her exhibitions include Memorial Park(Palais de Tokyo and Paris, 2013), Sand Theater(from Playtime, Culture Station Seoul 284, 2012), and The Whales -- Time Diver(National Theater Company of Korea, 2011).