People / Critic

Between Digital Interface and Graph Paper: Chung Hee-min’s Figure and Ground

posted 01 June 2021

Yung Bin Kwak

As is well-known, Chung Hee-min deals with the renewed status of images in the midst of digital milieu via the medium of painting. While few critics disagree with this type of general assessment, most of them seem to stop short of pinpointing what exactly makes her works singular at all. In a catalogue essay for EVE, a group exhibition of which she partook, I wrote that her oeuvre “suspend the hierarchical dichotomy of ‘figure and ground’.” In this short piece, I’d like to render that argument much more conspicuous by making references to her more recent works. .

Let’s begin with 〈I Stared at the Field You are Standing in His Dank Mouth〉 (2019), wherein a “damp imaginary space inside the mouth of a dog, freely wandering on the streets” was putatively posited. Shown at the 《Young Korean Artists 2019》 exhibition, this work was not only the single work Chung presented, but, more significantly, was said to depict the world seen from the inside of the dog’s mouth. According to the official caption, this “haptic scene” unfolded in the gallery space by means of corporeal images such as “teeth, eyes, and fingernails” as well as sculptural mass embodying materiality of saliva, of which the space inside the mouth is reminiscent. Nonetheless, it is quite doubtful whether this work readily serves to “brin[g] the viewer into a complete momentary immersion.” We are not saying that this painting ‘failed’ to achieve the goal. Rather, the problem concerns the very idea that this work should “bring viewers into immersion.”

At stake here is the peculiar fact that problems of reading images arise less at the level of ‘interpretation’ than at the dimension of ‘description’ of the work in question. For, more often than not, the latter determines the horizon of the former. Even when the above-mentioned caption belongs to the artist, it is virtually impossible to bring such description to one’s mind while looking at the work on site, let alone grasping the perceptual correlation between the two. Setting aside the painterly work, allegedly portrayed as a “haptic scene,” for the moment, the exact relationship between the painting and translucent physical materials scattered on the gallery floor, along with the figure of flowers blooming on top of them remains entirely opaque. Why are the resin, sitting at the bottom of flowers, for instance, rendered translucent? Why are the flowers’ configurations jagged, evoking pixelized digital images? More fundamentally, specifically how does the flat, plane painting relate to the objects on the floor? These questions call to mind the fact that her works constitute less the object of ‘iconological’ or ‘iconographical interpretation’ than that of ‘topological determination’ or ‘description.’ As to this issue, three points need to be elaborated on- all of which directly resonate with the evolving trajectory of Chung’s works and its implications.

My Old Faded Palette, 2020, mixed media, dimensions variable. Image provided by MMCA.

To begin with, the simplest way to read the flowers on the floor is to read them in terms of digital/flat images’ desire or yearning for ‘substance’ or ‘volume.’ 〈Song of Childhood〉 (2019) is arguably the most glaring example of this desire. Shown at 《An Angel Whispers》, her solo exhibition at P21 last year, this work was Chung’s first audiovisual image work to date, unfolding the abovementioned topoi of nostalgia, lack, and melancholy by means of a child’s narrative. Functioning as the metonomy of digital image ecosystem, ‘surface’ is almost obsessively presented as lacking ‘volume’ and ‘depth.’ This leitmotif of ‘absence’ corresponds to the body, the ultimate feature that the angel lacks in Wim Wenders’s film Der Himmel über Berlin/Wings of Desire (1987) (To be sure, this film is the background from which Song of Childhood, along with the title of the exhibition itself, is derived) On the other hand, this ‘absence’ is no less powerfully evoked by the child’s ‘memory of squashing’ “tofu, cheese, and jelly”, food items s/he encountered at a local store with her/his mom, infused with the sense of touch and materiality. That is, lack is twofold. Missing, or lost for good here is not only the childhood but also the material tactility. (No wonder how critical writings on Chung’s oeuvre such as ‘Crying Data’ by Kim Jung-hyun or ‘NAVY: Long and Sad Blue(s)’ by Yi Hyun are pervaded by the topoi of sadness and melancholy)

Secondly, one must note that the flowers in question are far from a simple ‘substance.’ Rather, they come close to pixelized flowers blooming on the translucent soil or mound. If the translucence of the former suggests the liquid crystal of digital devices, the flowers with pixelized contour lines retain the features of digital interface as well. Are they ‘substance’? Or ‘failed attempts to become substance’? Regardless of our answers, these questions are bad ones as long as they evaluate digital images negatively, i.e., in terms of ‘lack and absence’ against the backdrop of the putative ‘substance.’

In other words, the real question concerns how to avoid painting the gap between digital and analog, or ‘flat surface and materiality/sculpture’ with the topoi of ‘lack’, ‘nostalgia’ or ‘melancholy’, let alone an ambiguous rhetoric of ‘dialectics.’

Noting how her canvas is “a place where immateriality of digital image and materiality of the painting are traded,” art critic Kim Hong Ki, for instance, rightly points out that “the fascination towards the immateriality of the digital image and the aspirations for the materiality of canvas and paints coexist.” (These topoi of ‘trade’ and ‘coexistence’ can also be found in 〈Climbers〉 (2020), the most recent audiovisual work Chung made with Yong-a Lee and Seungho Chun, where ‘descent’ into the water is equated with ‘ascent’ or ‘climbing’ towards higher objects) A question is raised, however, when he adds that, “while fascinated by the immateriality of the digital image,” the artist “resists with the materiality of the canvas and pigments.” Does she “resist” the immateriality or, rather, insist that it must be ‘restored’ by- or ‘back to’- materiality? However similar they look, differences between the two, if any, is decisive.

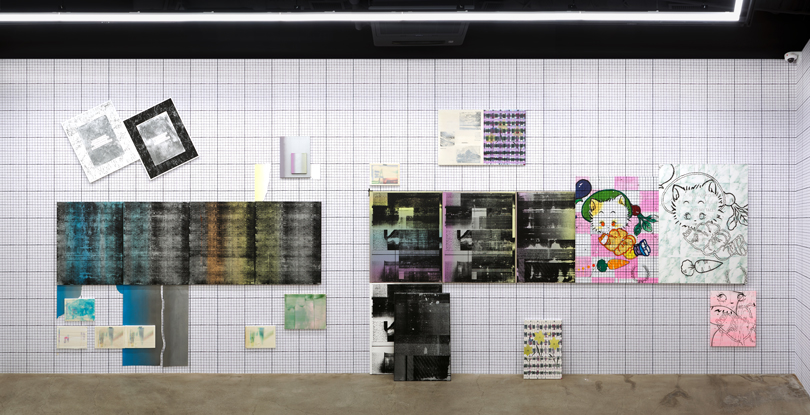

《If We Ever Meet Again》 (021 Gallery Daegu, 2020) Installation View. Image provided by MMCA.

Highly suggestive here is 《If We Ever Meet Again》 (Jun.-Aug. 2020), Chung’s most recent solo exhibition to date. To be sure, the same topoi of loss and absence appear to be no less present (e.g. ‘Greeting that Has Never Arrived,’ ‘Missing Cat,’ ‘You Will Miss Me’) More (un)noticeable is the background that covers one fraction of the gallery space and its implications. It is graph paper, which even secured its firm place in the catalogue. Not only does it overlap with the afterimages of minimalism, it also intersects with digital image pixels. Still, it sits firmly within the sphere of analog dimension. Does the artist, once again, attempt to ‘revert’ digital interface back to the analog materiality of graph paper? I think not.

Let’s recall my 2018 essay, where I wrote Chung “suspended the hierarchical dichotomy of ‘figure and background.’” Grasping her repeated attempts to apply or superimpose thick pigments on the canvas, thus rendering thickness more conspicuously pronounced, solely in terms of the hierarchical dichotomy of ‘analog vs. digital,’ is doomed to replay the melancholic Blues, desperately ‘compensating’ for the ‘loss’ in the former. In contrast, Chung asks anew the question of what constitutes the background, or the foundation of contemporary images and visibility in general, by introducing graph paper into the gallery space, if in part- not unlike the flickering fluorescent light. Precisely in this sense, despite the topoi of melancholy and absence she has constantly foregrounded or turned into her main figures, Chung’s oeuvre in its entirety must be read anew from the perspective of this ‘suspension.’ Let’s meet over there. ‘If We Ever Meet Again.’

※ 이 원고는 『2020 국립현대미술관 고양 레지던시 입주작가 비평모음집』에 수록된 것으로, 저작권자의 동의 아래 게재하는 글입니다.

Yung Bin Kwak

Yung Bin Kwak is an art critic, currently a Visiting Professor at Yonsei University, with PhD (diss. The Origin of Korean Trauerspiel) from the University of Iowa. Winner of the 1st SeMA-Hana Art Criticism Award in 2015, he served as a juror at 2016 EXiS (Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul), the SongEun Art Award as well as the POSCO Art Museum ‘The Great Artist’ competition in 2017. Publications include ‘Ancient Futures of