Artist Yoo Geun-Taek has used Korean hanji paper to summon mundane objects and experimented with the properties of paper, brush, and ink as part of his journey toward the modernization of East Asian painting.《Layered Time》 (February 24–April 18, 2021, Savina Museum), his first solo exhibition in four years, demonstrated his shift in attention to aspects of today’s turbulent times. His new works reflect the changed landscape of our pandemic-era reality as well as the political conflict between North and South Korea. This review canvasses Yoo’s course of work with particular attention to the relationship between image and materiality. The artist’s technique of creating rough textures on paper to create a sense of depth is a strategy for internalizing the subjects of his experience.

〈Some boundaries-NewYork Times〉, ink, chalk, and tempera on hanji, 148×270cm 2019. Image provided by Artinculture.

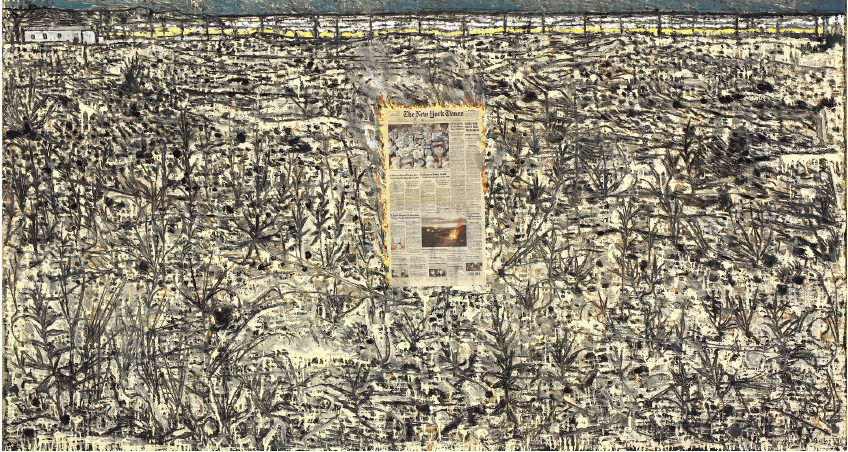

Yoo’s series The 〈Time〉 (2020), hung in sequence on one of the gallery walls, depicts newspapers, unfolded and laid out flat, burning. In the background of each painting, a monochromatic color field with a wood grain pattern impressionistic of a specific object fills the frame. Burning with the wood-grained color field as their backdrop, the newspapers are so level and square that they look almost heroic. Yoo used the seven similar paintings in the The Time series to record his thoughts on time, using newspapers, fire, and wooden tables as his subjects. 〈The Growth and Development series〉 (2020) on the adjacent wall, each labeled with subtitles, feature images against a background of overgrown grass, suggesting that the works stem from the same reflection on time.

What is particularly noticeable about 《Layered Time》 is that the materiality of the subjects in the background of the works and the subjects placed in the foreground of the works have equal presence in juxtaposition to each other. Although it’s difficult to distinguish the border between the two, the implications of “layered time” reminds of the causality between them, or rather, the degree of their overlap nearing unification. The materiality and images present in Yoo’s paintings often reveal themselves in a background-foreground relationship upon observation. This forces viewers like myself to reflect on the conditions of visual perception required to truly comprehend what is depicted in the paintings, like solving a difficult riddle.

Art from experience

While discussing the The 〈Time〉 series with me, Yoo suddenly looked at a painting from his 〈Morning〉 series (2020) and began telling me about his experience of the table depicted in it. “That’s the table where I eat every day. One day, I took off my glasses and observed the wood grain up close, and I found it so funny because there was a stream flowing in it” (interview with the artist, March 18, 2021). His observation led him to imagine a boat floating on the table, and so he painted a boat, sailing and creating waves in the stream that flowed from one edge of the table. The boat in the painting is smaller than the piece of bread or the folded newspaper also on the table, and surrealistically, it is carrying an elephant and a sailor, which would be much larger than the other objects in real life.

In a sense, an experience the artist had one morning with his table culminated in a narrative told through his physical senses. To borrow his expression, the “physical language” generated during the interaction between him and the table “crawled into the canvas” to become a scene. The table, having long been observed and considered by Yoo, sets complex and specific conditions that support the structure of his paintings in the Morning and The Time series. This substantiates Yoo’s definition of painting as “the impression and breath derived from the artist” and allows for us to fully gauge his intent to absorb the subjects of his experience through the act of painting.

As such, his meditation on the subjects of his paintings centers on the word “experience.” Tracing his works back to their sources, one is bound to find that all of his works begin with experience. Everything in his paintings was a subject of his experience or an experienced emotion. For example, one of his early series 〈Grandmother〉 (1995), which started with a portrait of his grandmother painted in 1991, seems to hold a special meaning to the artist as it was featured in his first solo exhibition in 1991. Repeatedly turning his experience of conversing with his grandmother into “drawings for his grandmother,” the artist revealed most candidly his inevitable process of creating images based on conversations—the progression of language—with a subject, whether it be nature, an object, or a person.

〈Morning〉, ink, chalk, and tempera on hanji 205×223cm 2020. Image provided by Artinculture

I noticed that the The Time series seemed to display an obsessive observation of certain images and elements of a perpetual transformation that disallows reduction of the images into objective subjects. Accordingly, I asked the artist if “depiction” and “contemplation” are how he materializes his experiences and their subjects into his works. His answer helped me understand the nature of the experiences that precede his subjects and paintings. He explained that observing the same object from the same perspective over an extended period was at once his habit, his mode of depiction, and his attitude. Gazing at the same landscape, coast, window, or table from the same position, he recognizes the “forces” harbored by these subjects. These include the moments of change incurred by these forces, the existential language created by the body in between the moments of observation, and time, or rather, narrative. The emotions Yoo experienced with the wooden table in producing the Morning series were transferred to the The Time series to become another form of backdrop as an attempt to project Yoo’s physical memory of the newspaper he unfolded at his breakfast table into a real-life space.

Yoo’s experiential perception and imagination (i.e., observing the wooden table and imagining the stream) seem to superimpose the solid materiality and stillness of the table and the fluid materiality of the stream onto the painting’s surface. This could also relate to the choice of the metaphor “skin of time” as the Korean title of Layered Time. As such, the perpetual material and pictorial change that occur on the arbitrary table in the The 〈Time〉 series is also experienced by the burning newspaper. The small fire, started in one corner of the newspaper, is imprinted in viewers’ minds as determinant of both the materiality of the subject and its transformation. It sometimes swallows the newspaper whole, turning it into ashes, and at other times spreads in the direction of the force in play (like the boat in the stream on the tabletop). Fire has often appeared in Yoo’s paintings, ominously soaring from a distant cityscape, spreading across a field or through overgrown weeds in a garden, burning something at the bottom of a fence, or flaring inside a TV screen to complicate an otherwise everyday scene. Burning newspapers communicate the anxiety and fear that exist and encroach on the artist’s body during moments as mundane as sitting at a breakfast table, and therefore they are real as a phenomenon perceived and triggered by his senses.

〈Wave〉 ink, chalk, and tempera on hanji, 150×207cm 2020. Image provided by Artinculture

Humane order

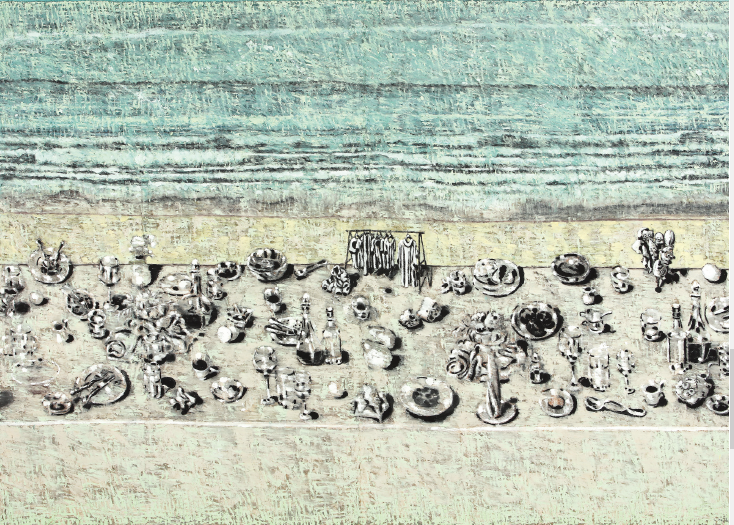

Yoo once wrote, “I want my works to be remembered as the most humane of orders” (Awful Landscape, 2013). By “humane order,” he means “dialing all focus to the forces and emotions being emitted by a subject,” and “channeling into the events occurring over time.” The pursuit or process of perceiving “subjects of experience”—particularly, the forces and emotions emitted by the subjects and their occurrences over time—were defined by philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty as “doubt.” This doubt, in Yoo’s words, becomes “humane order.” In the Growth and Development series, Yoo perceives landscapes and objects in his unique way, visualizing his phenomenological perception, as explored by Merleau-Ponty, using his own structure and mode of expression.

During the pandemic, a time that has been marked by isolation and an increase of senseless hate in everyday life, Yoo traveled to the shores, where people were scarce, and made a series of landscape sketches. Among them was the brush drawing On the 〈Yedanpo〉 (2020). He gazed at a bizarre landscape created by weeds that had grown wild in between paving stones, carpeting an entire parking lot at a closed-down amusement park. This led him to focus on the forces and emotions that approached him from this subject and the primal and futile events that were taking place there. He said that he was amazed by the intrinsic vitality of the weeds that had pushed their way up through the cracks in between the solid paving stones from roots seeded deep beneath layers of soil that had accumulated over time (interview with the artist, March 18, 2021). As someone aware of this incredible scene and as an artist, Yoo was inclined once again to express the “humane order” he so pursues in a pictorial structure that would contribute to the relationship of perception between himself and the (experienced) scene.

Throughout the series 〈Growth and Development, Growth and Development—Youth〉, 〈Growth and Development—Me〉, and 〈Growth and Development—My Birth〉, narratives with roots in the artist’s life and experiences anachronistically grow from their individual niches into real space. As a result, existential events are created through the uncertain yet tangible forces and emotions within their pictorial structures, just as the weeds in between the paving stones encroached on the surface of the parking lot. It’s almost as if the exhibition space was created by a chemical reaction between the subjects of experience and the artist’s experiential view. Yoo has used this method of visual structuring throughout the course of his works, including in the Growing Room series, the Scene series, and the smaller and larger serial works modified and derived from the two. As the artist said, “Painting is an act of finding and entering a space,” and in a sense, these works propose new perceptions of the pictorial space resulting from the combination of forces generated by the subject and the artist.

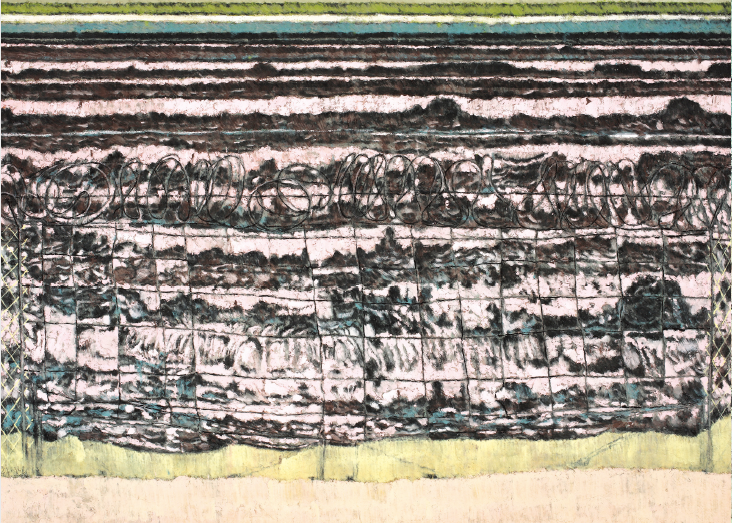

Painting can be described as the act of bending down and looking into a nook or toeing a border. In this exhibition, the series 〈Standing at the Edge〉 (2018), 〈Some Boundaries〉 (2018–2019), and 〈Waves〉 (2020) demonstrate the possibility for the pictorial space—created by the combination of forces and their direction of action—to exist in real life. For example, it is the space that is created when one identifies a point or a line within the structure of a painting through which to obsessively enter a series of new forms and spaces.

With Yoo’s experiential view in mind, I was particularly drawn to the 〈Waves〉 series. The space inside the paintings, with a beach in the foreground and the sea in the background, divided by a wire fence, expands into dozens of new spaces, such as those created by the refracted images of the crashing waves on the other side of the fence. This is similar to the burning newspaper on the table in the The 〈Time〉 series. As a result of the accumulation of Yoo’s repeated experiences of the ocean, the beach, and the forces and changes that engaged him, I was able to perceive, contemplate, and experience the energy of the fragmented space. An understanding of the existential structure of division communicated by the image of the waves obscured by the fence followed.

〈Some Dinner〉, ink, chalk, and tempera on hanji, 204×295cm 2019. Image provided by Artinculture

Spatiality in East Asian painting

Yoo also works with woodcuts. Perhaps the cohesion of the forces resulting from his subjects of experience and humane order (the order of phenomenological perception) is not completely unrelated to the sensitivity of woodcut prints. While Yoo still practices East Asian painting and uses paper, brush, and ink, he has also long been working with woodcuts because they are similar to these media yet open up new paths of experiences when the characteristics unique to paper and ink present him with limitations. In Korean painting, the intimate reciprocity between the paper, brush, and ink generally reveals its full potential within the infinite space ultimately created by the ethereal rice paper as it absorbs ink. But what Yoo wanted from his paper, brush, and ink was the potential for more direct and spontaneous expression led by the senses, not the materials’ inherent properties suited to traditional landscape paintings. “If I were to say what I want to say, the words would all seep into the rice paper and the picture wouldn’t speak,” he once said; this problem was, in a way, resolved by a turn to woodcuts (interview with the artist, Mar. 18, 2021). He began to take any kind of wood and carve it swiftly and extemporarily without any preliminary sketching. Through such work, he seems to have thoroughly tested all possible methods and attitudes for communicating his view of his internally experienced subjects through other media. In other words, while looking for a way to leave intact in his paintings the combined forces that occur when wielding a brush, he discovered the swift, candid, and direct fabrication method of woodcutting to be a suitable alternative.

Yoo once said that drawing is “an act of mimicking the breath of the subject.” He has mostly worked in brush drawing, and this method accompanied by the act of gazing is almost like feeling one’s way through a subject. In this regard, the significance of his woodcut technique, which is mediated by painting and drawing, clearly seems to have contributed largely to resolving the myriad obstacles he has come across in his career. Yoo experimented with and developed the characteristic thick, rough texture of his works early in his career. Materialized through a dialectical relationship between chalk and ink, the surface of his paintings could more accurately be described by the term “thickness.” The thickness of the surface, reinforced by paper grafts and irregularities, becomes something closer to a space. This is pictorial space he pursues, where the cohesion of forces occurs. For example, in producing works early in his career, Yoo would add touches of chalk and ink in between paper grafts to create physical layers on the painting’s surface. The chalk, which floats on the surface of the paper, and the ink, which is absorbed by the paper, would diverge and intermix in the grafting process to engender subtle tremors in the supporting body. And as these layers created a sense of space, Yoo would secure more room to squeeze in and fuse the languages that formed between him and his experienced subject. He called this an event or a phenomenon that occurs every day on the land where he stands. Yoo has named Chinese painter Bada Shanren (1624–1703) and Korean painter Jeong Seon (1676–1759) as the figures who most inspired this work process. From his explanation of the sense of space in Bada Shanren’s realist attitude and Jeon Seon’s mediatic painting (perfected in works such as Manpokdong Falls [dateable to 1700s]), I could tell that Yoo related to the painters and their experimentation with spatiality in East Asian painting. Yoo’s recent works, which involve grafting multiple layers of paper together, roughening up the surface with a wire brush, and using chalk and ink to achieve thickness, are an attempt at bringing out pictorial structure through the properties of the media. This can be seen as a painterly strategy of bringing the subjects of experience into the inner structure of the perceptive subject that is the artist himself.

※ This article, originally published in the April 2021 issue of Art in Culture, is provided by the Korea Art Management Service under a content provision agreement with the magazine.

Ahn So yeon

Art Critic