"Utimately everything disappears" is a statement which captures Kim Atta's previous works. They have developed dialecally through preservation, dissolution, presercation, and, ultimately, dissolution. Recently, he went a step further. In his Project Drawing of Nature series, traces on the canvas show things both visible, and how they influence each other. As he says, "Anything thart exists relates." Even in the moment everything disappeare, existence takes its first breath again, creathing a new cycle of life. This id part of "the world's reasons" he wanted to reveal through this project.

- **Kim Atta/ Photographer** Kim was invited for a special exhibition by the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. He has also held solo exhibitions at the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art and at Rodin Gallery in 2008, as well as at the International Center of Photography (ICP), New York, in June 2006. He represented Korea at the 25th Bienal de São Paulo in 2002. In addition, he is the author of 12 books, including The Museum Project (Aperture Foundation, 2005), ON-AIR (Steidl/ICP, 2006), Monograph Atta Kim (Hatje Cantz, 2009), and other books published by major Korean publishing companies such as Wisdom House and Hakgojae. His work forms part of collections at many notable museums in Korea and around the world. After running his Museum Project and On-AIR Project, Atta Kim has since run The Project - Drawing of Nature. While carrying out this latest project, he learned that one needs to prepare a great deal in order to attain meaningful results. As he puts it, “I believe that art can heal mankind’s wounds.”

Dictating The World's Reasons

It was early November 2011, and a drizzling rain was hastening the arrival of winter. I was on Gombae-ryeong, a ridge of Gangwon's Jeombong Mountain, when I had a singular experience. I saw a painting that nature itself had been painting since June 2010. More than a year and a half of time was inscribed in all the different traces left on the canvas. And with each one of these spots -- neither their form nor their origin could be explained -- something was taking shape there, something along the lines of an abstract painting. Blossoms of mildew, tracks of raindrops, the path of a bug, all now traces on the canvas. Marks from an unseen wind and the sunlight peeking through the clouds again and again; remnants of some mysterious workings beyond our ken. The work in question was part of The Project Drawing of Nature series, launched in 2009 by Atta Kim.

Kim Atta_The Project Drawing of Nature -deep forest in Korea-1_currently in progress

For this project, the artist positioned canvases in around thirty historically significant locations around the world to collect traces of nature: Gombae-ryeong and Hyangno Peak, Bodh Gaya and the banks of the Ganges in India, the island of Pharos (the matrix from which Greek philosophy emerged), the banks of the Yellow River in China's Henan Province (the birthplace of Eastern thought), Manhattan, a Native America reservation and Santa Fe in New Mexico, Hiroshima and Tokyo in Japan, Beijing, Venice, Switzerland, Siberia, Chile, France, Tibet, and more besides. It is a project that is still going on today. Kim's previous work, the Indala series, began with a focus on the cities of the world. The urban areas in question seemed to have been sucked into a world of intangible grayness, but their nuances were all subtly different. So it was with the works drawn by nature. The same period of physical time -- two or three years -- passed by all over the world. But the differing specificity of the spaces in which that time was embodied resulted in different traces on the canvas. Kim's work involves making the invisible visible: the flow of time, the subtle waves of nature. As he began The Project Drawing of Nature, Kim said it would "net the thought and principles of the world that we do not see with the eyes, take dictation from the principles of the world with the nature of Eastern thought, which is referred to [in the West] as the 'drifting cloud.'"The underlying philosophy is what is crucial here.

In a treatise titled The Era of Video Culture and Integrative Imagination, the philosopher Lee Ki-sang praised Kim as someone who "has gone beyond photographic technique, beyond the science of photography, to bring his work into the realm of photographic philosophy." Quoting Vilem Flusser, Lee predicted the arrival of age when people would "attempt philosophy with form rather than with text." In this new age of video culture, he said, the photograph may become an optimized means of philosophical conceptualization and contemplation. Already, Kim was at work expressing the profundity of the world of Eastern thought through the technologically advanced Western medium of the camera. To him, the photograph was the "most powerful weapon for revealing the world I had interpreted." And, should the need arise, he is prepared to put his camera down at any moment. This, finally, is what he did with The Project Drawing of Nature. With his special exhibition for the 2009 Venice Biennale, he was establishing a stable place for himself as a world-renowned photographer, so his choice was baffling to many. But it was a logical development on his part. Kim describesThe Project Drawing of Nature as "both a deconstruction and a revival" of his previous work, ON-AIR Project.

See and Touch The Spirit

A key strand of thought running through Kim's previous work was the idea that "all things eventually disappear." His pieces had followed a dialectical structure of preservation, disintegration, preservation, final disintegration. In the 1980s, his series The Portrait  constituted an act of preserving the spirit through photographing Korea's intangible cultural heritage. After that, his Deconstruction series consisted of shocking scenes showing nude people in rice paddies and on highway roadsides posed "as though sowing rice." The figures were cast into nature without any social indicators, and ultimately became nothing, like rocks in a field. All descriptions of the self that existed before that point are negated. The dismantling of established conceptions marks the beginning of full-bodied challenge of the modern thought and practices of Western society, with its origins in the proposition that "I think, therefore I am."

constituted an act of preserving the spirit through photographing Korea's intangible cultural heritage. After that, his Deconstruction series consisted of shocking scenes showing nude people in rice paddies and on highway roadsides posed "as though sowing rice." The figures were cast into nature without any social indicators, and ultimately became nothing, like rocks in a field. All descriptions of the self that existed before that point are negated. The dismantling of established conceptions marks the beginning of full-bodied challenge of the modern thought and practices of Western society, with its origins in the proposition that "I think, therefore I am."

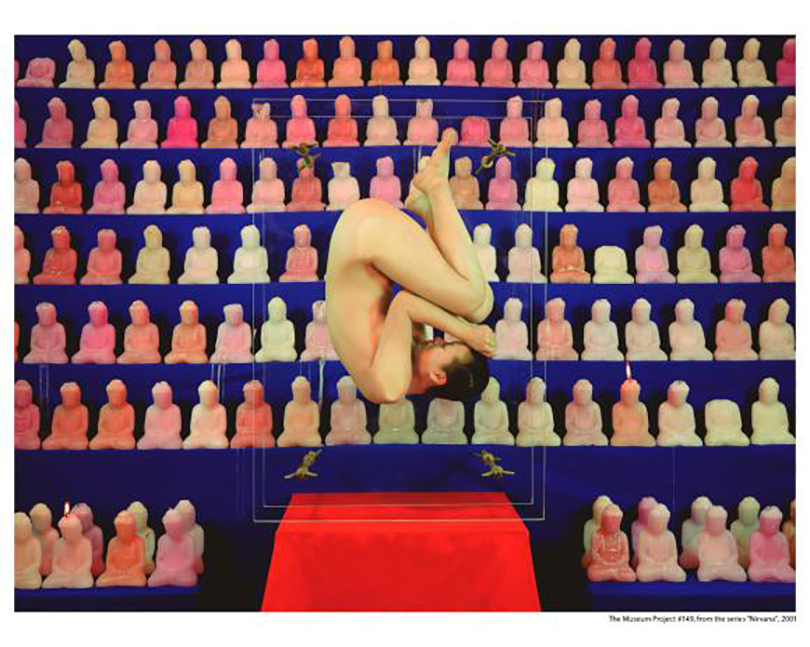

First unveiled in 1995, the photographs in the Museum Project series show people surrounded by acryclic boxes, like properties in a museum: prostitutes, disabled veterans, couples making love, ordinary family members. These pictures deconstruct the concept of the museum as a place that preserves only important things; they turn it around to stress that no matter how trivial something may appear, it is still worthy of preservation in a museum. Overlapping with the Buddhist idea of the buddha nature existing in all things, the images are indicative of the place that Kim occupies in Korean cultural history. Until the early 1990s, religious themes had a very important meaning in Korean spiritual culture. Leading literary figures like Kim Seong-dong, Yi Mun-yol, Lee Chung-joon, Ko Un, and Park Sang-ryuk wrote works that dealt with such weighty themes as religion and death. And under the political repressions of the 1970s and 1980s, religious themes constituted an important part of Korean cultural history, expressing the spiritual struggle to surmount a vulgar reality.

Written in the early 1990s, Ko's novel The Flower Ornament Sutra put a period on this long march. With the thesis that "all things change, and the only truth is change" in the world, the very subject in this framework ultimately disappears from the world of the sutra. One sentence in particular -- "All things eventually, however, disappear" -- assumes absolute importance. It may be the use of the word "however" that captures the most attention in this sentence. It implies the importance of all individuals prior to their disappearance. The Museum Project was a process of acknowledging and preserving the individual incarnations attained just before this final disintegration. Even as Korean literature after Ko Un cast aside grandness of narrative and focused on the private world of trivial everyday experience, Atta Kim has continued following his own path. Through the extensiveness and universality of visual art, he has achieved a transcendence of locality and temporality of thought. His thought, indeed, had expanded beyond the cultural context of Korea and toward the international.

ON-AIR first made a splash at a 2006 exhibition of the International Center of Photography (ICP). Consisting of four sections ("Superimposition," "Monolog of Ice," "Long Exposure," and "Indala"), the series gave diverse visual form to the proposition that "all things eventually, however, disappear." "Monologue of Ice" was, in fact, part of the museum deconstruction project. For this, the artist carved ice sculptures of some of the most venerated things in the world, objects revered for their eternal value, and made an artwork out of the process of them slowly melting away. Even today, Kim continues to astonish by showing the disappearance of socialist icon Mao Zedong, capitalist art symbol Marilyn Monroe, and himself. In socialist and capitalist societies alike, all that is solid becomes subject to deconstruction. The more vociferously something argues for its preservation value, the more determined Atta Kim is to take it apart.

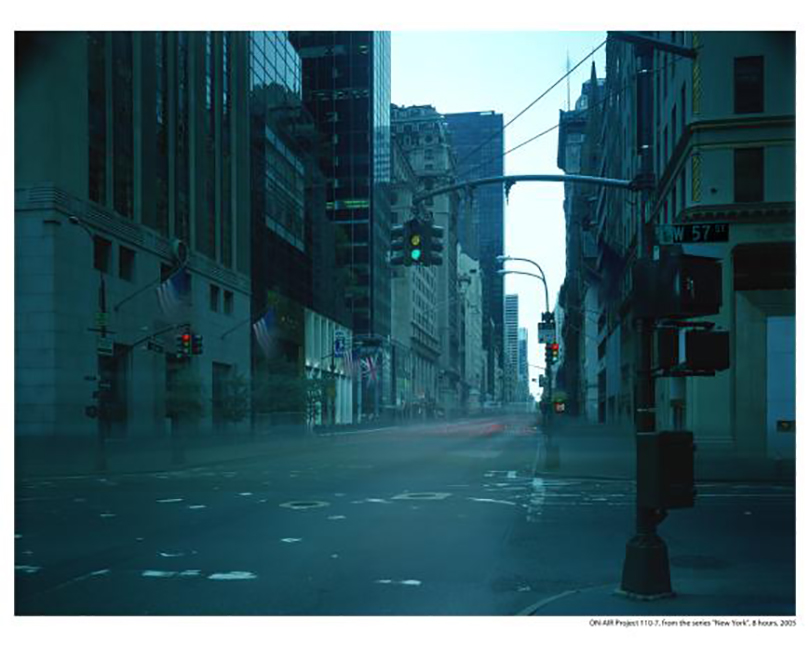

Kim Atta_ ON-AIR EIGHTHOURS New York 110-7_2005

Before the things that disappear in ice, there are the things that disappear by themselves with time. One series involved using long exposure times so that slowly moving things were captured in the frame, while quickly moving things disappeared. For eight hours, Kim filmed New York City's Times Square, with all its people and cars coming and going. The buildings remained, but the moving people and cars were present only as traces of light and flickering shadow. All things eventually, however, disappeared. And as they disappeared, this remained. Atta Kim succeeded in making the seemingly incompatible -- existence and absence -- coexist in one frame. A medium, photography, that is trusted to give authentic records of existence recorded instead disappearance and absence. And with this, Kim took his first steps over a boundary.

The World that dissapeared into Indala,

The Face of Indala that came out within The World

In the Indala series, even slow-moving things disappear. It is a work that inspires a sense of religious sublimity. Kim has taken tens of thousands of photographs of vibrant cityscapes and put them all together, but the end product, paradoxically enough, is a zero -- empty space. What other work so precisely gives visual expression to the Heart Sutra's assertion that " Matter is void "? All things are contained where nothing seems to be present. "In the West, the void is empty, but in the East the void is full," Kim says. All disappearance is predicated on existence. And all that exists eventually disappears. The ontology of Eastern thought, with its circular reasoning, is embodied in the artist's photographs through images that are not images. It is an act that he has applied to a growing number of areas through masterworks on the themes of the Dao De Jing, Lao-tzu, and Western art.

Kim Atta_ ON-AIR Indala series- Vincent Van gogh_2009

With the Indala series, Kim crossed the boundaries of genre. The most crucial elements in photography are the object, the camera, and the photographer, but in this series the most fundamental of these, the object, has disappeared. And with the disappearance of the object, the artist has effectively transcended the genre of photography. The genre has dismantled and transcended itself. Distinctions of color have also vanished from these objectless photographs. What we see cannot be described as simply "gray." It is the color that exists after color has disappeared, the canvas capturing traces of color as the convergence of light. No colors or forms remain in Kim's photographs. In Indala, it appears as though all principles of the image have been extinguished, but it is an image in which all images are encompassed. Principles of form disappear, genre transcends genre, and all that remains is the structural act of photographing, over and over again.

With The Project Drawing of Nature, even the compositional camera behind all those photographs has disappeared, along with the artist himself. Kim is always ready to let go of the camera that provides him with the means of embodying his philosophy. When the artist disappears, it is a different matter entirely from the "end of the subject" in the 1960s. Just as even the subject of structure disappeared from the Flower Ornament Sutra world in Ko Un's work of the same name, the author himself has vanished from his project. Kim has put into practice the idea that "all things change, and the only truth is change." This applies not only to the content of his work, but to the artistic process, and to the artist himself. Atta Kim took a step back, and the world, nature, began to show its face.

Even though its artist is nature working in wide open spaces, the frames, surprisingly enough, are not the same. Some parts are smeared more deeply; others bloom with more of the white blossoms of specks. These unequal forms are what nature paints as it takes the brush; if we insist on attributing them to anything, we must look to small elements in the environment. The parts with towering trees differ from those where trees are sparse, the front surface of the canvas from the back. The effects come from tiny stones whose presence we never perceive. We must not refuse to acknowledge things simply because they are not visible to our eyes, because they cannot be explained. They influence and are influenced in tiny measures, leaving traces of themselves behind. In its thrall to the myth of objectivity, Western philosophy did not trust in what the eye could not see. The microscope and telescope did help to expand the realm of the visible, but such things are still accessed by reason, perpetuating the myth of objectivity. They fail to attain to an ontology for a greater universe outside our view.

The end of Western Civilization is now being signaled all around us with the crisis of modern civilization. A contemporary reality in which "Western philosophy and Western aesthetics are receding and Eastern thought is being presented as an alternative" is more urgently in need of Atta Kim's work. The traces left behind of the canvas show us an interplay of influence between the seen and the unseen, all connected within a relationship. "All that exists is related," Kim says. He shows a great cycle of life, where even at the moment when everything seems to have disappeared, existence is once again vividly breathing. This, perhaps, is just one part of the "principles of the world" that he sought to present when he began The Project Drawing of Nature.

[Photo courtesy of Kim Atta]

Lee Jin-sook / Art Critic

Lee received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Seoul National University’s Department of German Language & Literature. She received another master’s degree dealing with Kazimir Malevich at the Russian State University for the Humanities’ Division of History of Art. She runs the programs “Between Russian Art and Literature” and “A Thematic History of Western Art” and teaches at Dongduk Women’s University, Yonsei University, and Chung-Ang University. She regularly contributes to columns such as “Lee Jin-sook and Artists of Our Era” (Monthly Top Class) and “Lee Jin-sook’s In-depth Reading of Art Books” (Joongang SUNDAY). She is the author of the Russian Art History (Minumin, 2007), an introduction to Russian painters, The Big Bang of Art (Minumsa, 2010), a criticism on young Korean artists, and a collection of art essays called Depending on Beauty.