Hwang Jai Hyoung, known as a “miner-artist,” became a miner to capture reality on the canvas, sublimating the life he witnessed firsthand at the mines into art that seethes with passion. He later embraced nature, encompassing all its creation, and worked with hair as his medium to express the longing of human souls. For Hwang, “reality” isn’t just a mere form, but a vessel of introspection that stalwartly mirrors life. Hwang Jai Hyoung: Restoration of Human Dignity (April 30–August 22, 2021), a large-scale retrospective exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA Seoul), collected some 40 years of his artistic journey dedicated to laborers and minoritized groups in society. I see Hwang’s course of work as a “new breed of baroque paintings.” His symmetrical and moderated forms are philanthropic, reflecting the artist’s tendency to see “stars of hope” at the unseen end of a mine tunnel.

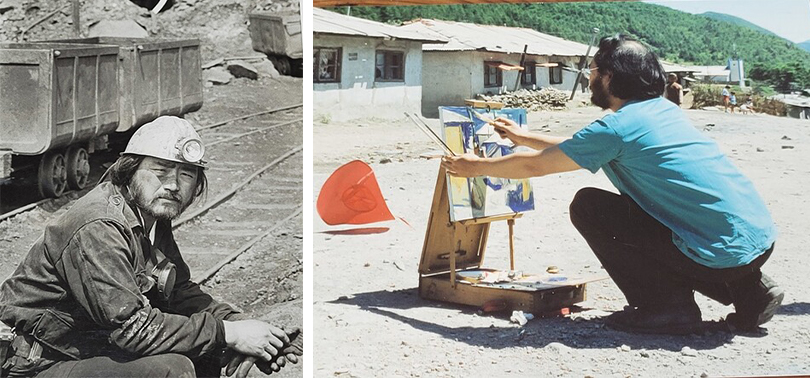

LEFT: Hwang during his time as a miner at the Taeyoung Mining Plant in Taebaek, 1982–1983, RIGHT The artist painting on a makeshift canvas in a coal-mining village in Taebaek, early 1980s. Images provided by Art In Culture.

Hwang Jai Hyoung

- Hwang Jai Hyoung was born in Boseong, Jeollanam-do, in 1952 and graduated from Chung-ang University with a degree in painting in 1982. As a student at Chung-ang University, he founded the artist group Imsulnyeon (officially “Imsulnyeon at 98992”) in 1982 with Park Heungsoon, Chun Junyeup, and Lee Jonggu—returning students to the art department at the time—and held an inaugural exhibition at Deoksu Art Museum. He worked both as a miner and a painter from 1982 to 1985, when he gave up mining due to irritant conjunctivitis. In 1984, he held his first solo exhibition Dirt to Grasp and Land to Lie On at the Third Art Museum; he would go on to hold six more solo exhibitions by the same title, the last one in 2010. He has also held solo exhibitions at the Gwangju Museum of Art (2013), the Park Soo Keun Museum (2017), and Gana Art Center, and participated in numerous group exhibitions including The Development of the Third Painting (Kwanhoon Gallery, 2981), Exhibition of Illegally Seized Prints (Geurim Madang Min, 1991), and 15 Years of Minjung Art (MMCA, 1999). Between 1992 and 1996, he painted murals at Gohan Catholic Church, Taebaek Chilpyo Farm, and Hwangji Catholic Church.

Van Gogh

“I wanted to paint the hands that planted, harvested, and carried the potatoes. I wanted to speak about how honestly they cultivated a meal.” Vincent van Gogh, who saw life’s last hopes shining like stars in a mine, went on a short mission to a coal-mining village in Borinage, Belgium, exactly a century ago. He was quickly fired from the job for fraternizing with the miners and forsaking his dignity as a missionary. Later, when he became an artist, he painted miners and eventually the sky full of swirling stars that he used to gaze at from the mine. Hwang, known for his outstanding facial features and build and respected for his exceptional empathy, became a miner at the same age that Van Gogh became a painter, residing in the mining village in Taebaek until the age of 70. He unswervingly devoted himself to painting in Taebaek, which wouldn’t let go of him, despite the promises he made to his dedicated spouse that he would only be gone a year. Perhaps he became possessed by the spirits of the 72 wise men of Dumun-dong.

Van Gogh, who believed that he was alive in place of a brother who had died being born, was determined to dedicate everything, including his art, to those impoverished and in need. He pursued absolute purity instead of secular success and sought to escape worldly interventions by painting at the risk of failure. All modern painters are descendants of Van Gogh, who heralded in modernity by escaping from the standardized disciplines of the artistic academy. The discourse surrounding him corroborates the shift in artistic valuation standards in which value is placed less on the work itself and more on the individual who created the work. A work’s specificity, in connection to autobiographical or psychological information about the artist, has come to personify the work. In other words, the agent and the subject (that is, the artist and the work), are tied as a package by the artist’s signature. The notion of “authenticity” runs through the two as a whole. After all, artists ultimately end up devoting their mind and body to their spiritual core.

, oil on canvas, 193.5 × 130 cm, 2008. This monumental painting, which marks a pivotal point in Hwang’s course of work, depicts a scene in which the golden glow of a sunset is reflected on the surface of Tancheon Stream, a stream formed of coal dust and sewage, in Sabuk. Images provided by Art In Culture.

The Miner-Artist

Hwang wanted to reach the deepest and innermost part of this spiritual core. Hwang has lived in the city of Taebaek since he moved there in September 1982. He began his career as a miner at the most grueling and dangerous mines—including those in Hambaek, Jeongdong, and Gujeol, which didn’t have so much as drawbars—digging up coal and carrying it out of the mines on his back. He would move to a new mining plant every two to three months and paint on the weekends, leading a double life. Mining towns saw their heyday in the 1980s. In 1978, the Korean government built the Hwagang Apartment in Jangseong-dong, Taebaek, to house mineworkers; toward the hill behind the apartment building, there were shanties along the long alley of Hwasan-dong where plant employees who didn’t make it into company housing lived in groups. People lined up outside the coal mines in Jangseong, Cheoram, Hwangji, Tongni, Gohan, Sabuk, and Dogye in hopes of finding employment. The business was so lucrative that there was a saying in the mining villages, “Even a dog passing by carries a 10,000-won bill in its mouth.”

However, this saying only applied to the owners of the plants and surrounding taverns—the miners themselves were still poor. Hwang, then in his late 20s, physically experienced the poverty-stricken life of miners, hoping to leave behind paintings that represent the spirit of self-sacrifice and reportage as his legacy. This is precisely the kind of worldview seen in The Road to Wigan Pier (1936), a classic work of literary reportage by George Orwell in which the author vividly describes the life of miners during the Great Depression and the rise of fascism based on his visits to the coal-mining regions north of England. Orwell’s hyperrealistic depiction of the coal-mining villages is in commune with Hwang’s hyperrealistic paintings. The writer’s spirit of parrhesia, inexorability, and bold statement takes on a new level of brilliance within the ethical life led by Hwang as a reportage artist, as Hwang reveals reality through the form of “silent poetry” that is painting.

Miners extract coal from dark places hundreds and thousands of meters below the surface of the earth. The UK, which achieved a new industrial revolution by directing solar energy toward mining operations, put forth Margaret Thatcher’s slogan “TINA (There Is No Alternative)” to defeat the miners’ strike of 1984, going on to globally change the course of “carbon democracy,” and launch a full-scale war on terrorism against the Middle East. In a way, the UK’s infringement on Middle Eastern democracy was a ploy to maintain its carbon democracy. In 2015, the UK’s last two remaining coal mines were closed down, putting an end to its 300-year history of mining.

Though they are both fossil fuels, while coal could be considered the pearl of the ground, petroleum has become the so-called diamond of the ground. As coal ran out and oil became powerful, the global shift from one to the other became unstoppable. In 1989, a coal industry rationalization policy heralded the end of the Korean coal-mining industry, and the miners once praised as “industrial warriors” who drove the wave of economic growth referred to as the “miracle on the Han River” lost their jobs and dispersed. The correlation between the reality of fossil fuel capitalism and democracy is important. We often think that democracy has to do with human society while energy resources and climate change have to do with the natural environment. Political theorist and historian Timothy Mitchell overturns this idea: “Carbon is an element that sustains and also constrains democracy from within.” The driving force behind the labor movement that led the protest for Korea’s electoral system was made up of miners and railway workers—warriors of democracy who mined and transported coal.

, oil on canvas, 227 × 130 cm, 1981. This hyperrealistic painting of ragged work clothes that belonged to a miner who died in a landslide accident at the Hwangji coal mine in 1980 won the artist a participation prize at the 5th JoongAng Fine Arts Prize (1982) in addition to attention from the art scene. Image provided by Art in Culture.

New Baroqueism

Vast forests from the time of trilobites and dinosaurs remain compressed underground. Excavating a coal seam in this environment requires highly hazardous and intense labor. Performing such hellish work in narrow, suffocating tunnels, miners would frequently have to pour out the sweat in their boots and take off their undershirts to squeeze them dry. Tension always presides over these dark tunnels ridden with odorless, colorless gas, where water tanks could blow up and ceilings could collapse at any time. There is a reason the Korean word makjang, meaning “the unseen end of a mine gallery,” is used as slang to describe something so bad that it couldn’t get any worse. But to miners, makjang holds a sublime significance as the space of coal-mining work—the last opportunity to work, proof that one has reached the edge of one’s life, and a place where life and death intersect. If there were an artistic term that encompasses these meanings of makjang, it would have to be “baroqueism,” derived from a term for distorted pearls.

Hwang, who has conveyed his message in various ways in a visual environment that has rapidly evolved since the 1980s, has pushed the boundaries of commercial and institutional painting and opened new paths. At the Jangseong Mining Plant, he worked 375 meters below sea level, equivalent to 975 meters underground. The blasting work he did down in the narrow tunnels required him to endure crumbling quakes and deafening explosions. His job, at the same time, was to just stay put, trapped in a world of coal dust and dirt where he couldn’t make out the shape of his own body let alone what lay ahead, even with a safety lamp. Once the mining crew stepped into the makjang, they couldn’t eat or drink. When scorching weather coincided with caving days, coal dust and chemical smoke would fly around like gnats, making eating impossible. The more coal they mined, the further the abyss of the makjang would extend.

Gilles Deleuze spoke of baroque and its dark, enclosed space—the monad of the soul. Mine tunnels are filled with piles of burnt debris and creased coal seams that beget more creases as they stretch on endlessly. In the 1970s, when the rate of fatalities at coal mines was at its highest, the average number of miners who lost their lives at mines amounted to 230 to 250 a year; even in the 1980s, the number exceeded 200. Additionally, 250 people died due to pneumoconiosis on average every year. The longest existing English word “pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis,” when broken down, refers to “a disease caused by the adhesion of invisibly fine silicon in volcanic ash or sand dust to the lungs.” This perpetually incurable disease is a divine punishment reserved for those who provide humans with fire. Orwell wrote, “It is only because miners sweat their guts out that superior persons can remain superior. You and I and the editor of the Times Lit. Supp., and the Nancy poets and the Archbishop of Canterbury and Comrade X, author of Marxism of Infants—all of us really owe the comparative decency of our lives to poor drudges underground, blackened to the eyes, with their throats full of coal dust, driving their shovels forward with arms and belly muscles of steel.”

Throughout Hwang’s course of work, two contrasting modes of expression have forged internal conflict and variation. Formally, his works harbor a sense of weight that respects symmetry and moderation yet essentially contains chaos and inconsistency. When an action has a contradictory hidden intention, the stylistic result infallibly falls under the category of baroque. Baroque in this sense refers not to the historical Western trend limited to the 17th century but the “style of expression fundamental to humans” evident in any given time and place. As declared by Spanish art historian Eugenio d’Ors in Du Baroque (1935) and by French art historian Henri Focillon in The Life of Forms in Art (1936), baroque is the intense clash between light and darkness, the agitation of emotions, the moral and religious affection for minoritized people, and the abyss of form birthed by coincidence and chaos. As such, baroque sees human nature as a constant and it is fundamentally a mode of spiritual expression. Baroque opposes classicism more fundamentally than romanticism, despite the latter emerging in opposition to classicism. After all, romanticism is but an episode in the story of baroque’s fate. Hwangji 330 (1981), which mourns the death of miner Kim Gwangchun in a landslide accident, is not a work of critical realism, but our time’s most immaculate work of baroqueism.

In 1972, a Korean artist portrayed clear, hyperrealistic waterdrops and water stains to evoke an Orientalist fantasy for European viewers, but this act was a reflection of subjectivity that had nothing to do with the social truth. Ten years later, Hwang presented an amazing, almost new-objectivist image that shows viewers a mirror image of themselves. Hyperrealism was part of new subjectivism, which originated from the concept of “veritas” (truth) and developed first into anarchist Dadaism in the 1920s and then into a form of social critique. This type of exposition presupposed the artistic testament to the external and visible “reality.” The canvas painting of actual clothing once worn by the deceased was produced from a photograph, but it creates the illusion (a hallucinatory effect) of the actual subject being projected onto a clear mirror. Hwang, who wanted to capture the grimness of reality, strictly omitted the background and filled up the vertically elongated canvas with an extremely zoomed-in image of the work clothes.

The deeply furrowed baroque-style surface, formed by the stark contrast between light and dark in the fluid wrinkles of the flat structure, feels like a thick veil that masks the independent entity. The worker’s identification patch—a nametag printed with his mining plant of affiliation, name, photo, and contract period—and an undergarment labeled with the brand name and even size approach us like the armored ghost in Hamlet that emerges from the darkness. At the time of this work’s production, Hwang remarked, “The hole is gaping.” A sense of intense pressure is evoked by the white undershirt with tattered seams. The image appears to be saying something to us with its swaying gesture, but we can’t quite make it out.

How does the artist transcend the dimension of visibility to relate to the invisible yet “actual” subject? In a way, this is a painterly hypothesis because the painting gives the impression that it wants to portray the abyss by remaining amongst uncertainties rather than couple up with the visible, objective world (subject). The object in the painting and the objective, neutral, unifying, and visible outside world are two completely different things. It is impossible for us to see something without any mediation.

This is not a realist work. It bears no relevance to socialist content that heroizes laborers or documents the ills of capitalism. Hwang’s paintings of miners—works like Symptom (1980), which reflects the pain of the Sabuk Coal Mine Labor Struggle of 1980—and his numerous landscapes are neither direct nor seditious. They are products of onsite contemplation of the possible link between art and politics. Nevertheless, to define them as critical realism on a petit-bourgeois level would be to underestimate the impact of art. Hwangji 330 is a new form of baroque art in that it unites the mirror image and pictorial image to lure viewers into a hallucinatory illusion instead of a perspective-based optical illusion. Perhaps life and death are divided by a small entryway, a thin, ruffled curtain that leads into the afterlife. There is no background to this entryway; only a stiff hanger that casts the veil of the dead like a frail skeleton.

, oil on canvas, 91 × 117 cm, 1985. Between 1982 and 1985, Hwang worked as a miner at Hambaek and Jeongdong in Gangwon-do in hopes of discovering the “essence of art.” Lunch reflects his experience of eating packed lunches covered in coal, lit only by his fellow miners’ headlamps. Image provided by Art in Culture.

Darkness

Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name is Red (1998) introduces miniaturists during the Ottoman empire who painted at risk to their own lives. Breaking rules to try something new meant putting one’s life on the line. The state of perfection these artists sought lay even further than the incessant practice in which they became able to paint their subjects even if they went blind. Hwang, like these medieval miniaturists, paints darkness from memory. He doesn’t paint his subjects as he has seen them, nor does he reproduce nature “just as it is.” Whether painting a figure or a scene, what Hwang pursues is “structure and harmony that parallel nature.” He asserts, “Light may not be the essence of life—rather, darkness may be the essence of human existence. There is a kind of darkness that wants to rebloom in the midst of any despair or doubt. And beyond it is light.”

We experience death in strictly meeting the demands of art. Death in this sense is not annihilation, but an inquiry into our futility or the limit of our autonomy. Everything in this world is used to fuel our contemplation on death.

After completing a basic, honest drawing of a subject, Hwang removes the subject from his sight and touches up the image little by little using a brush and a palette knife. For him, painting is ultimately an act of depicting darkness. Honesty in painting is not a subjective feeling but an act of endlessly confronting the subject’s hidden core in order to ultimately achieve accord. The precise, unconscious core lies hidden, buried, and sometimes damaged within a subject. Hwang has passionately absorbed and internalized classic hyperrealist techniques from the 1970s new figuration movement and neo-expressionism, seeking to pursue the spirit of realism inherent in new objectivism.

As it turns out, two tendencies—Van Gogh and Jean-François Millet’s reflective naturalism and new-objective realism—exist in equilibrium inside of Hwang, whose portraits have also dealt with history’s long silence. As Buddhist monk Heungseon describes, Hwang’s paintings, which have survived through grueling periods of history, are a “tribute to those who crossed the river of that era together.”

, oil on canvas, 116.8 × 80.3 cm, 2000. Hwang witnessed social poverty and human alienation at the coal mines, but spoke of hope in the end. “Every time I see their faces, I feel the presence of the sublime. I thought that I should give names to the unexpressed expressions, the uncried cries, and the people deprived of their names.” Image provided by Art in Culture

The Four Mirrors

Hwang’s attitude toward art leans less toward the trends of contemporary times and more toward the intellect and sentiment of the Middle Ages, including the faithful and relentless execution of self-control, introspection, command, order, and knowledge. This is largely similar to the psyche or existential attitude of Van Gogh, who endlessly attempted to view himself through his neighbors. The 13th-century French scholar and Dominican friar Vincent de Beauvais produced illustrated collections of ancient and medieval poems to solidify his knowledge. Likewise, Hwang’s world lies adjacent to the four books he wrote in an attempt to access life’s truths: The Mirror of Nature, The Mirror of Principles, The Mirror of Morality, and The Mirror of History.

The life of French art historian Émile Mâle, who was born the son of a coal mine engineer and influenced the history of iconography, was also riddled with self-command, order, and the sharing of knowledge. In this sense, Hwang’s art is intrinsically distant from critical realism, socialist realism, grassroots realism, communal divine command theory, and aggressive divine command theory, all of which are part of the discourse on the artistic movements of the 1980s. The sentiment that runs through his early works including Symptom, Hwangji 330, Lunch (1985), Bath (Unwashable) (1983), and Baekdu Mountains (1993–2004), as well as his hair series, can be seen as baroqueism in its modern sense. The transition of his artistic theme to “the wrinkles of life and the weight of labor” in 2011 was a result of the artist shifting his focus to multi-resonant, baroque-style images of natural science.

, oil on canvas, 162 × 112.1 cm, 1993–2006. After the 1990s, Hwang captured the abandoned mine villages and scenery of Gangwon-do on canvas, intent on documenting the ironic issues caused by Korean society’s compressed growth. Image provided by Art in Culture.

Misconceptions about Abstract Art

Abstraction has so far been understood as a result of renouncing the illusion of space. But abstraction precedes illusion. An image or form is “created” in a figurative space outside of visual coordinates where new and unfamiliar perceptions are forged. Therefore, abstraction shouldn’t be deemed as emptying an illusional space composed of forms and narratives. The impetus behind abstraction is not the elimination of everything based on self-directed abstinence, but the sense of the moment at which one finally intends to see an object after the collapse of vision (blindness) caused by painting. Our eyes do not see as something appears. Though it may feel like the landscape before us enters our retinas to unfold like a screen inside our brains, it actually isn’t that simple. Our eyes analyze information as soon as we register it, categorizing and processing the lines, colors, and movements in the landscape separately.

What is important here is not the political attitude of the artist, but the political attitude harbored by the work. Here, “attitude” refers to an attitude of resistance against politics, and “resistance,” more accurately, is that which is against politics that subjugate art as a sort of medium. The resistive strategy “utilizes the senses that overflow our body” (Kim Wonbang). All art is ineluctably political. The problem lies in the theological, enlightenmentist view of art that sees it only as a political object and seeks to separate it from bodily existence. This is the quagmire in which realism finds itself mired.

, oil on canvas, 206.5 × 496 cm, 1993–2004. Hwang reworks his paintings over several years in order to capture the essence of his subjects. It took him 10 years to complete Baekdu Mountains, which was based on his experience of seeing Baekdusan Mountain in heavy snowfall at night. When he revisited the site the next morning to paint the nightscape he had seen, he found that such an impression had vanished, leaving mere quietude behind. He redirected his focus from coal mines to nature in the 1990s to expand on his idea of reality. Image provided by Art in Culture.

Symptom

In Hwang’s Symptom, the sky, resembling a coal stream, takes up two-thirds of the canvas; underneath it, massively deforested swathes of land with tractor wheel tracks stretch endlessly toward the horizon. Not a single patch of grass remains on the ruined wasteland. This gruesome landscape reminds viewers of T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” a poem familiar to those who went to college in the 1970s. Part 1, titled “The Burial of the Dead,” begins with the line, “April is the cruelest month” and ends with, “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

The full poem ends with a Sanskrit incantation: “Shantih shantih.” Shantih means “peace,” and it is believed that repeating the word three times frees one from mental suffering, physical pain, and detriments of natural disasters. Liberation from pain and the sharing of love form the moral foundation and political axis of Hwang’s course of work, and Symptom marks the course’s beginning. This monumental painting made a mark in the history of Korean labor movements, capturing the pitch-dark period just before the artist settled in Taebaek as a miner and just after the Sabuk Coal Mine Labor Struggle (April 1980) and the ensuant Gwangju Uprising (May 1980) occurred. The strip of light lingering at the end of the wasteland and the raw flesh exposed at the stubs of the ruthlessly cut trees in the painting suggest a fervent will to latch onto hope, and it is upon this point that we hear and shudder at the sound of pansori, a traditional Korean form of musical drama deemed modern-day baroque.

〈Sulfuric Acid〉, oil on canvas, 112.1 × 162.2 cm, 2008. Hwang’s landscapes are characterized by their thick matière. The title of this experimental work, which Hwang produced in an attempt to capture reality, alludes to a society that has turned blackish-red due to pollution. Image provided by Art in Culture.

Asters and Women Laborers

Women, including factory workers, Hwang’s sister and mother, and the bereaved families of the Sewol ferry disaster, frequently appear in the artist’s paintings. His experience of the labor scene began at a night school for female factory workers, who accounted for 90 percent of all laborers at the time. The girl in Aster carries a mugwort-filled mesh bag on her head and her younger sibling on her back. In this aesthetic scene, the girl hurries toward a windy hill covered in aster blossoms.

This work illustrates the heartrending story of a girl who has lost her parents and must raise her younger sibling on her own. It may remind viewers of the verse, “Eighty percent of what raised me was the wind, ” from Seo Jeongju’s poem “Self-Portrait.” The same history continually repeats itself all over the world. But Hwang does not stop at mournful retrospection, instead paying attention to the powerful vitality that does not despair at life’s bitterness, but sublimates it into a valiant language.

mountain village; Kwon the Coal Hewer (1996), with its lamenting gaze covered in coal dust; The Weight of Life (1999), which captures shanties clustered like fallen leaves; One of the Ridges of Sunset (2003), reflected on a slate roof topped with stones; Heated Floor II (2004), painted as a yellow glow seeping out from a snow-covered shack in a rugged valley; and Sunlight of Gohan (2006), depicting a shed and shack on a mountain slope, all attest to the warm compassion the artist feels toward those who have only “dirt to grasp” and no “land to lie on.”

With the introduction of the factory system to industrialized societies, labor, land, and currency all began to be seen through the lens of sale value. What was once economic fiction turned into the organizing principle of our society. As labor is an act bestowed particularly upon humans, human society has in every way become adjunct to the economic system it has created. If humans and nature fail to be protected, are shredded whole by the “devil’s millstone” that is the market economy, and fall into the abyss of degeneration, no society or individual will survive the consequences of this outrageous fictional system.

portrays rows of huts that look like harmonicas and are occupied by Korean laborers who were forcefully conscripted under Japanese colonial rule. Image provided by Art in Culture.

The Painter in the Picture

Eight miners are dining in a dark, narrow pit, their single-bulb headlamps acting as their beacons of life. They eat hurriedly as they illuminate each other’s lunchboxes with their headlamps. The spurts of light reveal the turbid pit, contouring the unseen end of the mine tunnel that Orwell called “hell.” The rays, intersecting like “distorted pearls” amid the crouching bunch, form a thick, tensely dynamic curve. Hwang tends to be conscious of the point upon which viewers’ gazes most often end up settling, which he either emphasizes or uses to hide meaning. The head of the miner in the very front is lowered to precisely highlight the rail with the figure’s headlamp. This rail is the only escape route out of the pit.

Artists often instinctively feel the urge to include themselves in their paintings of crowds as an acting “empathizer.” In a sense, this could be an act of autograph, of setting oneself up as a witness to a situation that eventifies (stages) the “here and now” where potential encounters take place. In viewing Lunch, it is easy to forget to “gaze” as viewers may be dazzled by the density and intensity of the miners. On the upper right corner of the canvas, one miner is painted in distinct profile. His pensive mood sets him apart from the other miners, who are hurriedly stuffing their mouths with food, and the miner next to him eyes him as if this is out of the ordinary. In this painting of a scene of extreme labor, Hwang creates a “live form” by inscribing the darkness with his own face, thereby inserting a mental story.

Tentacular Imagination

The combination of the all-embracive and accommodative Baekdu Mountains and Hwangji 330 forms an enclosed chamber of the soul that functions as an altar, sparks inspiration, and makes viewers wonder how Hwang synthesizes his art. Hair is the part of the human body where the soul indwells, and it is partially in charge of emotions. Human dreams are envisioned in the head, which is why the head is a symbol of power. Hair accounts for the largest amount of carbon in the human body, and it most closely represents humans in that each hair is merely a fine strand.

Carbon fiber is characterized by its ultralight and superstrong properties. It has been useful in reducing the weight of airplanes and automobiles by more than half of their previous iterations, thus significantly reducing carbon dioxide emissions, which is why experts in related fields have said, “If the 20th century was the age of silicon, the 21st century will be the age of carbon fiber.” The MMCA Seoul retrospective Hwang Jai Hyoung: Restoration of Human Dignity showcased many of Hwang’s hair works from 2016 to date, alongside his oil paintings. According to the artist, hair stores information, acting as a kind of film that becomes engraved with one’s course of life and the relationship with one’s environment. In his works, hair from unknown sources comes together to create images. In this sense, the use of hair in his works is more implicit than explicit, embodying a confession to or a declaration of what can’t be known. In approaching reality, Hwang always keeps a safe distance from realism as a result of representational thinking. His work is defined by the movement of the sixth chemical element on the periodic table as it happens to be Earth’s lifeline, a ray of sunlight in the ground.

Memory is an act of stirring up a Pandora’s box of pain, anxiety, shame, and fear to find traces of joy and hope within the whirlpool. Hwang’s portraits and landscapes made of hair are metaphors for an integrated circuit in which indecipherable pieces of information are intermixed; perhaps they are also emblems of the love the artist feels toward the collective “marginalized” of the world, including himself and his relatives. But the idea that everything is connected is not just indefinite; it tends to be impotent because when everything is intertwined, one cannot find a beginning. This idea raises a problem in that it makes us incapable of breaking old habits that need to be discarded or improved. Instead, we are doomed to repeat them. Karma enforces a way of thinking that is centered on certain identical people and intimately tied to the type of totalitarian thinking that endlessly marginalizes all of those who are non-identical, including women, people with disabilities, people of color, and sexual minorities.

Hwang has demonstrated firsthand not only the need for frontiers of social reform for laborers, but also such frontiers for institutional and sustainable care for minoritized groups. Thus, Hwang’s work is simultaneously an art of memory that repeats this demonstration in everyday life and a form of natural science that encompasses life as a whole. There are points of disconnection (or an inability to connect) between women and men, able-bodied and disabled people, children and adults, animals and humans, and people of color and white people because they are, after all, different. We must recognize the value of what is unique to minoritized groups and differentiates them from the majority. Humans—in fact, all living organisms—do not live everywhere. We live in specific places and are necessarily connected to some things and not others. At the same time, these connections are accidental. Regardless of our intentions, we can be minoritized, meet other minoritized groups, and develop allyship.

In Hwang’s hair works, tentacles detect images in his memory. He puts long, hard thought into materializing into painting tentacular forms that serve the memories, movements, breaths, and visual aspects of his works. How do we faithfully sustain the richness and viscosity of thought over time? In Hwang’s case, he converses and exchanges emotions with his paintings while thinking like a brain that remembers the painting’s flat surface.

, hair on canvas, 181.8 × 227.3 cm, 2012–2018. Hwang reproduces his past works and depicts significant social events with hair. This work metaphorizes the political undertakings that led to the sinking of the Sewol ferry. Image provided by Art in Culture

The Product of Living Labor

To Hwang, when something is “lifelike,” it means that there is nothing static about it. This is to say that something lifelike has a dynamic rhythmic “resonance.” To borrow a Marxist term, a painting becomes lifelike through “living labor,” and the labor and life of the artist become “preserved” in the painting. This idea assumes a certain indexicality in painting (i.e., that a painting connotes labor and life) and an internal connection between narrative and form. To elaborate, anyone can relate to the “mass appeal” of a painting depending on how the artist chooses to preserve his or her life and career in the painting. Even upon the arrival of the new economy, painting was able to capture the mass appeal of the hic et nunc (“here and now”) with the same sensitivity through which it has captured living labor. Here, “new economy” refers to the post-Fordist condition, cognitive capitalism, or network capitalism that began to grow conspicuously after the 1980s. The new economy targets our cognitive and affective abilities—just take a look at how social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook market our lives.

Paintings hold leverage in the economic system because of the perception that they contain the artists’ life and labor. The status of artists is still the highest in the hierarchy, which is why their works make for expensive auction items. Paintings reveal the way we live as subjects of commercialization. Hwang visualizes narrativized (internalized) experiences in a way that is different from realism as claimed by critics and artists on the “activist side” of the 1980s Minjung Art movement. According to David Hume, such a narrative implies a “bond” rather than a “necessary connection.” In this sense, the narrative takes the form of self-discovery necessary and valuable to the process of traversing darkness.

The Devil’s Millstone

Hwang, now in his 70s, unveiled only one new work upon his invitation to hold a retrospective at MMCA Seoul. The rest of the works were from his oeuvre of the past 40 years, handpicked by Hwang to be included in the exhibition. The new work is a magnified replica of a metal jig (faux bait) used in lure fishing, communicating a message that humans line up to get caught, lured in by the faux bait that is the system. At one point in time, the term “realist” meant a person who would unwaveringly comply with reality. At least in the 1980s, realism stood as a political alternative to capitalism. At the time, “real socialism” subsisted if only in the final stages before its downfall. However, the world has changed. Today, there is a much deeper and more pervasive sense of depletion that is almost a sense of cultural and political barrenness. “Capitalist realism” is so infinitely variable that it always manages to subject itself to reality. The hedonism that neoliberalism offers is a (faux) bait that keeps us clinging to the same impulses.

Economist Karl Polanyi was appalled by market capitalism’s utter destruction of humankind. Specifically, he was angered by economic exploitation’s negation of human dignity and soul and market capitalism’s treatment of humans as mere market products. Hwang adopted the phrase “the devil’s millstone,” an expression Polanyi borrowed from English poet and painter William Blake’s poem to describe the capitalist market economy, as the title of his new work. In today’s society in which depression is prevalent as static form of mania, people are set adrift, impulsively circulating from one trivial joy, issue, trend, and program to another. Anti-capitalism is widespread within capitalism, yet it only reinforces capitalist realism rather than undermining it.

A century ago, Vincent Van Gogh’s life took a turn as he lived amongst miners in Borinage. There, he examined up close the wretched working and living conditions of the miners while nursing the injured. And as he prayed for them, he asked basic questions on the human condition. Hwang also cultivated a comparably significant life out of a mining village. Why must so many suffer so much just to survive? Why is arduous human labor never properly recognized anywhere? In a place shunned by everyone, Hwang used his tentacles to make an artistic discovery and take care of his neighbors. He wished to command precise senses based on correct judgment, an endeavor in which he succeeded.

LEFT Standing on My Land, hair on canvas, 162 × 227 cm, 2016. RIGHT Exposed Face, hair on canvas, 162.2 × 130.3 cm, 2017. Hwang brought his experience of mining villages back to life in this ongoing experiment of breathing reality into the stories of laborers. Image provided by Art in Culture

In Korea, miners have now disappeared into history; since the 2000s, they and the people of mining villages have also largely disappeared from Hwang’s works, replaced by mountainous townscapes and images of alleyways in Taebaek where they used to live. Outstanding among these landscapes is Walking a Tightrope (1996–2007), in which a house, lumped together with mounds on a mountain slope covered in melting snow, appears almost like the hide of a Paleozoic animal. A man carrying something in his hand is walking, glancing up at the slippery walkway ahead of him. The path, parallel to the collapsed embarkment, is acutely cut off by the frame but it is implicit that the man must walk up the wet slope. This image hints at a precarious and perilous future. The man in the picture likely represents both miners in general and the artist himself. The painting appears to be true to the artist’s confession, “To me, the canvas was reality and the very hope of transforming reality.” There appear many walkways in Hwang’s paintings. Walkways are where accidental encounters take place, where various persons intersect at one spatiotemporal point. On walkways, the spatiotemporal continuum that defines human destiny becomes even more intricate due to the disintegration of social distance; the continua are uniquely fused. The chronotope of the walkway is where new beginnings are begotten and events come to an end, hence, walkways befit depictions of events governed by chance. This work seems to utter, “Long live life as it is” (Dziga Vertov).

Hwang produces documentary artwork out of mundanity. He does not depict life as it is, nor does he add or alter anything. The image of a miner perhaps signifies his acceptance of the uncertain future approaching him day after day or the unfamiliar present at which he has already arrived. This type of present-ization may direct him to a small escape. Therefore, truth is a subjective opinion, a product constructed according to the artist’s expectations. The documentary format does not attest to reality; more than anything, it attests to the will to power of the format itself. “As it is” in the sentence “Long live life as it is” is a dynamic addition that reverses the statement because it is simply impossible for a documentary work to capture life as it is. A picture can never fully hold life “as it is.” The moment life becomes an image, it relinquishes its status as life and becomes its own “other”—a static object or doppelgänger of reality that is both realistic and surreal. Life inside a documentary can be everything else but life itself.

The Weight of Life (1999), in which houses and earth become lumped together, Black Cry (1996–2008), in which houses are huddled beneath a thick, colossal mountain, and In My Heaven (1997), in which a mountain village is covered in black coal ash, all capture aspects of a coal-mining village. An entire row of houses is slanted at a staggering angle, the houses’ window frames tilted 10 to 20 degrees toward the ground. It is said that windows and doors get completely distorted when a house suddenly tilts, but this kind of event does not even startle the people of a mining village. Instead, they laugh at the story of a miner who returned home from work one day and had to break down the door with an axe to get in.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, a renowned British writer of the early 20th century, once argued that the foundation of contemporary civilization was abstract painting. He was wrong. Modern civilization was founded upon carbon, amid which coal propelled democracy. The machines that kept people alive and the machines that built those machines all directly and indirectly depended on coal. The relationship between coal, industrialization, and colonization was the first and most fundamental link between fossil fuel and democracy. To understand this in a new way, we must test not our subject-centered ideologies or social consciousness, but our proper understanding of objects, that is, Karan Barad’s claim that objects aren’t single entities but manifold ones—that the mind and the world do not exist separately in external interaction, but rather interact on an internal level. Carbon comprises visible and sometimes invisible “ties” or “alliances” formed by the labor of the miners who excavate it. These ties and alliances do not allow any distinction between material and concept, economy and politics, nature and society, humans and non-humans, or violence and reenactment. As a result, it is impossible to not pay respect to the Hwang’s arduous endeavors, including his physical contemplation and attempts to discover all of the above in art.

1)Timothy Mitchell sees democracy from the perspective of the “actant” that is carbon. He argues that modern democracy is inseparable from coal mining, which thermodynamically powered the establishment of the political institution, and that while coal propelled and strengthened democracy, oil weakens it. Timothy Mitchell (translated by the Energy & Climate Policy Institution), Carbon Democracy, Saenggakbihaeng, 2017.

2)Shortly before his death, art historian Lim Youngbang published three books in a row: Humanism and Art During the Italian Renaissance (2003), Medieval Art and Iconography (2011), and Baroque (2011). In Baroque, he introduces in detail Eugenio D’ors’s thesis on baroque. D’ors proposed a table of 22 subordinates of baroque that categorized the manners in which baroque has historically presented itself; this table includes prehistoric, Buddhist, grassroots, and healing baroque. Literary critic Kim Hyun asserts that “Baroque is a viaduct that connects the 17th and 20th centuries, and it is a concept that is still alive.” Kim Hyun, “Poetics of Happiness/Dreams by Jegang, the God of Chaos,” On the Semantic Change in the Concept of Baroque, Moonjii Publishing, 1991, 163.