〈Skaters on Frozen Canal (Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, Seoul)〉 Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

Among the many theories on the origin of art, one of theory argues that art began when humanity started to ponder about what lies beyond their mortality. Faced with the humbling prospect of their utter demise, humans realized that they amount to nothing. Yet this realization prompted humans to desire to be something, and to resonate with humanity. Thus humans began trying to feel something invisible from the rocks and trees before their primitive eyes. From the fleeting encounters and experiences, they began to search for something eternal, then started to express such desires through forms made of rock and wood, or lines etched into cave walls. So-called primitive art began as a visual catharsis of sorts. Representation is a continuous trade between the visible and invisible. However, as humans gradually overcame their fear of death, they began to consider art as a means of fully expressing their desires. When human rationalism reached its peak and inspired humans to believe that they can control and summon even the seemingly invisible and intangible, so did the elaborate rhetoric and unfettered desire inherent in the language of art.

It is difficult to confine SONG Juho to any single genre of art, whether it is visual art, film, theater, or dance. With his uniquely distinct sensibility, he poses questions about art and the general pursuit of art. And now, the artist is reflecting back on his life as an artist and seeking the way ahead. Of course, his current self is not so much in a state of incompletion that has yet to fulfill something, but rather a state of open possibilities, capable of reaching any distance or incorporating anything without limit.

〈Skaters on Frozen Canal (Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, Seoul)〉 Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

The artist usually throws such a series of questions with his own body on the stage. Totally exposed without any medium in between, his body is not any sort of a symbol. Akin to slapstick comedy, his body intentionally twists, erases, and moves everything artistic and theatrical. His body itself serves as the means of manifesting all discourse on art, and casts doubt on all art, desiring for art that has yet to come. Sometimes his body shakes anxiously when faced with such desires, but openly shows that it is trembling instead of concealing it.

〈Nuit Beau Roman (Sungmisan Theater, Seoul)〉 Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

Facing the Frame, Overcoming the Frame

Like all discourse on humanity and the world, art came to comprise its own framework of reality by dabbling back and forth with ideal reality and material reality since the dawn of history. Parergon, which means ‘frame, is a portmanteau of the word ‘ergon,’ meaning human activity, behavior, work, and function, and ‘para,’which means ‘around.’ Thus, parergon or frame is a boundary that delineates what is part of the art from what is not. It is already widely known that Kant referred to the frame as a device or ornament that makes the beauty and absoluteness of the work, i.e. ergon stand out even more.

〈Nuit Beau Roman (Sungmisan Theater, Seoul)〉 Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

However, the German philosopher Georg Simmel argued against Kant’s views on the frame. In an essay about the Picture Frames written in 1902, Simmel argued that the parergon tries to idealize its contents (art) as the most perfect thing possible, while defining everything else as entirely non-artistic, lacking, and negative. Simmel asserts that such duality and binary border-drawing isolates art within the frame like a lone island. Jurij Lotman adopted Simmel’s thoughts on frames in the context of literary text, further developing the notion of the frame in terms of interpretation and reception. According to Lotman, the frame of literary text draws the borders that distinguish what is text or not. Lotman concurred that the way the frame highlights its contents, in fact, acts as a discriminant that distances the contents from what is outside the frame, isolating the work present within the frame.

His works since 2015 also address the ‘frame (para)’ that has and continues to comprise the discourse in all areas of art, thereby questioning the identity of the ‘work (ergon)’ within the frame. Sometimes he literally creates a frame by sticking tape on the stage floor in a rectangle. At other times, he rips the tape off the floor to remove the frame. Sometimes performers in his work slowly stumble across the rectangular frame marked on the stage floor. While the inside of the frame is the area wherein all works of art, including ones by his own work, are exhibited, it is also a domain that keeps the art trapped which should be broken down and rebuilt over and over again in order to prevent utter isolation. Performance History (Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, 2017) is also a history of all frames that have ever been made in the theater. When the performance begins, there is no boundary between the performers and the audience. At this point, distinguishing the audience from the spectacle bears no meaning.

Everyone makes eye contact, greets and talks with each other, and is free to move about throughout the space. However, as the 12 rectangular panels vary positions throughout the remaining hour and 50 minutes of the show, the spatiality of the theater changes dramatically. They not only impact the movement route of the audience but also change the viewing angle. The activities in the theater become strictly distinguished between showing and seeing, as an undeniable sense of certain hierarchy gravely takes hold of the theater in front of the audience under the pretense of art. Such playful twisting of the boundary between the stage and the audience seats, and between the actors and the audience members were already present in Cheering Cells UP (ARKO Arts Theater Small Hall, 2016). In this production, the performers randomly designate the position of the audience seats and crack their whips to wrangle the audience around. This performance also presents the manifestation of the authoritarianism committed in the theater in the name of art throughout history. Skaters on Frozen Canal (Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, 2018) sets the theater lobby, which separates the theater’s exterior from the interior, as the center of the performance. The performance presents an ostensibly indifferent sense of cynicism about the cruel gap between the illusion and reality of art, as well as all the drama of the world trapped within their own frames.

Parergon. This is the frame that kept art rigid in the name of art. The frequent appearance of various forms of fences as well as other tools like ropes, axes and shovels in his work signifies the artist’s determination to break down and overcome such frames that are endlessly made and categorized, as well as the artist’s attempt to answer the questions he continues to ask himself.

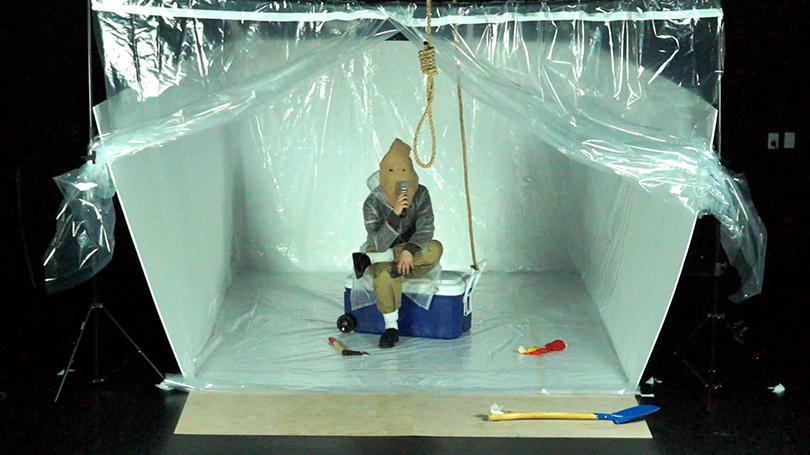

〈Coffin Club (Incheon Art Platform, Incheon)〉, 60min Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

Between the Two Worlds of Desire and Anxiety

Meanwhile, there are always two worlds coexisting and colliding on his stage. In Forbidden Plan (Seoul Art Space Mullae Box Theater, 2018), he presents a world that we wish to reach alongside the present reality. In Before It Turns Whiteout (Namsan Arts Center, 2018), a world already long forgotten collides with the present. In Boredom Growing up with Ever Expanding Universe (Seoul Dance Center, 2015), the artist himself stands before a flippant desire about a world expanding tremendously and an equally tremendous future. In Brightness Alone (Seoul Art Space Mullae Box Theater, 2016) presents his identity as an artist as well as a human being.

〈Coffin Club (Incheon Art Platform, Incheon)〉, 60min Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

He removes all exceedingly incomplete and perhaps deliberately artistic rhetoric from the gap between the two worlds that clearly branched part from a single origin, and highlights the remnant infantility through a staged visual image. This can be seen in the furniture and door made of thin paper that crumples so easily with the slightest pressure despite appearing to be fixed in place (In Brightness Alone), as well as in the hill of the artists filled with shamelessly crude tree, grass, and rock set pieces that allegedly went for realism (Forbidden Plan). his stage is a space of absence, where in methods that should exist and appear, do not. Perhaps such absence is his way of deliberately erasing all artistic rhetoric from a world in which even the artist himself remains fettered. Amidst the seemingly unbridgeable gap between the desire for the out-of-reach realities and the actual present, new possibilities remain open. his performances are the spatial manifestation of his determination for self-reflection and self-reinvention in the context of such new open possibilities. Questions that the artist asks himself about art and himself as an artist are found accumulated in the artist’s works from 2015 to 2019. His works are a compressed history of performance and a meta-critique. Perhaps then it is time for him to take that question and look beyond the theater walls. Considering how the impetus for all art thus far has come from the art and artists who voluntarily chose to remain in the periphery instead of the center, the time is ripe for him to provide such driving force for our art here today. I look forward to seeing him enter the reality beyond the frame of art he sought to overcome, via art, and begin to rattle the countless other frames existing in such reality.

〈Coffin Club (Incheon Art Platform, Incheon)〉, 60min Performance, 60min, 2019. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

※ This content was first published in 『2019 Incheon Art Platform Residency Program Cataloge』, and re-published here with the consent of Incheon Art Platform

Lee Kyung Mi

LEE Kyung Mi is a theater scholar and critic. She received a doctorate in German Literature from Korea

University before studying at the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf in Germany. Currently studying

the ‘aesthetics of the gap’ the moment occurring when performing arts go beyond their existing boundaries, and how that pertains to humanities, across the backdrop of the question of ‘theatricality.’ Occasionally working as a dramaturg, Lee seeks to find the point of intersection between theory and practice.