Seo Do-ho has long been at the center of conversations related to aontemporary art. His works examine displacement caused by cultural hybridization, something long seen as a fresh topic. Houses made od cloth changed traditionally heavy, solid architrcture into something lighter, more nonmaterial, feminine, and mobile.

- Sei Do-ho artist orn in Seoul in 1962, Seo currently lives in New York and London, though does work in many other places around the world. After studying East Asian painting at Seoul National University\, he went on to study at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), then received an MFA in sculpture from Yale University. His works explore the boundaries of the ego through place-specific installations under the themes of karma, relationships, and space. Seo took part in the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001 and the Venice Biennale International Architecture Exhibition in 2010. His works are part of collections at many internationally renowned organizations such as MoMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Tate Modern and Hayward Gallery in London, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo\, Mori Art Museum, Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, and Artsonje Center in Korea.

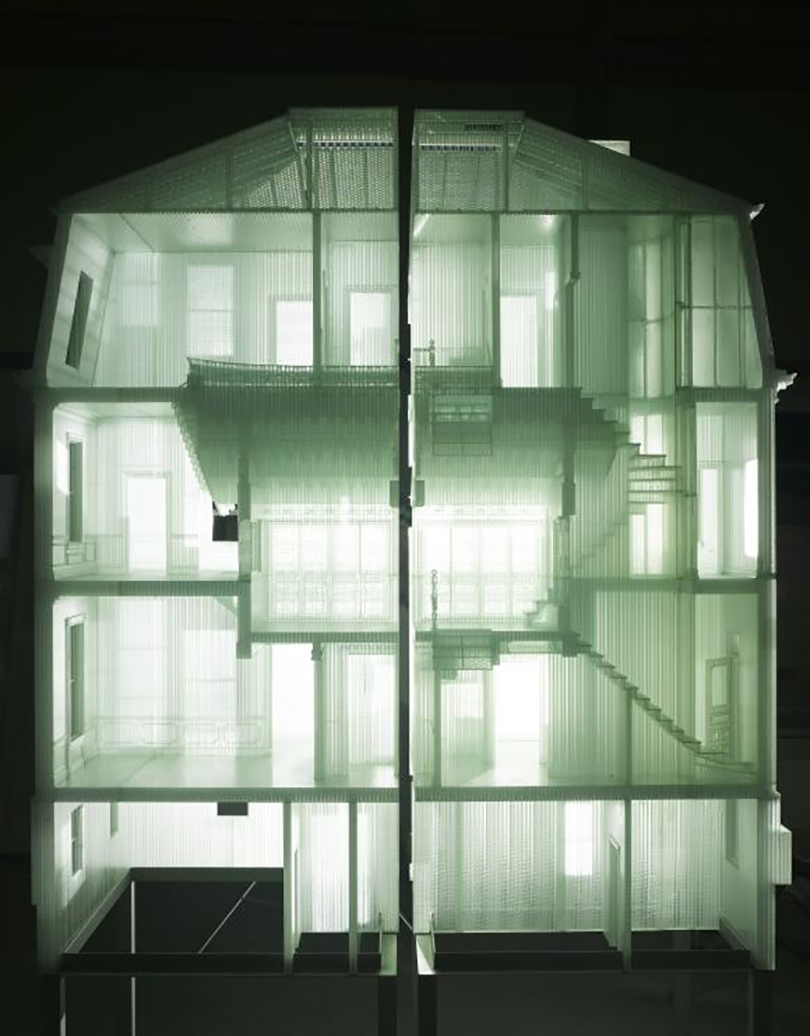

Seo Do-ho_Reflection1_polyester, fabric, metal armature_2005~2011

The Redined Aesthetic of a Born-and-Bred Seoul Aristocrat

Seo Do-ho is beautiful. His beauty can be sensed with the eyes, rings out clearly in the brain, inscribes itself deeply on the heart. His work seems enveloped in the difficult language of modern art's complicated discourse. But it remains striking even if you don't understand the discourse. With its plainspoken appeal to the viewer, the beauty pierces the armor of language.

Seo's name first became known to the world through work in which he used fabric to recreate the Korean-style Hanok home he lived in as a child. His father, Seo Se-ok, is a master of traditional Korean painting. The elder Seo built the house in the style of Yeongyeong-dang, a hall in Seoul's Joseon-era Changdeokgung Palace. The younger, in his turn, used that structure as an emotionally laden source material. Korea's traditional architectural culture deeply imbues not only the exterior, but the very aesthetic. The transparent shells float, phantomlike, in the gallery. This choice to make it transparent was inspired by the traditional changhoji, traditional Korean paper made from mulberry paper used in Hanok houses; the green hue, calling to mind the delicate, sumptuous texture of silk, is reminiscent of Goryeo celadon and the clothes and adornments in the paintings of Shin Yun-bok. In Paratrooper V (2005), which shows a tiny soldier clutching a cord bearing the names of three thousand people, the coloring recalls the richly pink lanterns that bedeck mountain temples on the Buddha's birthday. Lit from without, it sends a peculiar warmth and spirituality emanating through the gallery. The refined taste that comes through in Seo's choices of color and lighting are rooted in a traditional aesthetic that is uniquely Korean.

Delicate crafting went into the items that fill the house's interior: the bars and rafters, the tile patterns, the doorknobs, plugs, and light switches. Seeing this, one foreign critic called it "so beautiful that you are left dumbstruck." But this ability to turn trivial items into refined works of art is not merely a matter of craftsmanship. At the heart of this work is Seo's trenchant and emotional eye for objects. Nothing is done without care; in this, he recalls the aristocratic scholars of old Korea, with their attention to detail, their forbearance. Yet even as they, the aristocratic scholars of old Korea, establish this sense of refinement and moderation, they does not stifle their world with rigor. The aristocratic scholars of old Korea who love nature have often viewed its "naturalness" as the greatest of aesthetics. Seo Do-ho is carrying on this tradition.

Nomade : The New Human of the Globalization Era

Seo Do-ho has consistently occupied a place at the heart of modern art discourse. The sense of displacement engendered by his work's cultural hybridity has come across as a particularly fresh theme. In crafting his homes from fabric, Seo has taken something that has always been weighty and solid and made it light, immaterial, feminine -- something that can be transported anywhere. The result has transformed into an icon for the nomadic life of 20th century global capitalism. Indeed, the house is akin to a self-portrait for Seo, whose own nomadic life has taken him back and forth between the United States, Korea, and Europe. It all began in 1991 when he traveled to the US for his studies. In encountering these two opposing cultures, he found the greatest difference to be in space. Architecture, he says, shows how people live, and who lives there.

Two chapters in this architectural autobiography come in the form of Fallen Star 1/5 (2008--2011) and Home within Home (2011). Our story begins one day as this one particular Korean home is carried on the Tornado America and lands at an apartment in Rhode Island. As the moment of collision comes, differences move into the foreground, and everything can be seen clearly. This is why the work is done in miniature, filled with realistic detail. But it is in Home within Home that we see the collision shown not as a unidirectional assimilation, but as a process of peaceful coexistence. The moment passes, and communication is established between the two houses, bringing them together again as one -- this is when the single house gains its "transparency," where it might once again float off somewhere. Korean and Western architecture intrude upon one another and become a coexisting "home within home" -- a metaphor for the nomadic self.

Seo Do-ho_Home within Home 1/11_Prototype_Stereograph_2009

This understanding of the ego gives way to the contemplation of a proactive role for the nomad. Seo describes feeling "like the space connecting one culture to another." Now, with his active ideas for the Eastern perspective on objects, he is playing the crucial role of gateway, through which two different cultures flow and reorganize. Describing his 2011 work Gate, Seo says, "I saw the core of Eastern culture as being constant change and movement." His contemplation ("understanding the world as a single impermanent, moving and constantly changing") presents us with an excellent example of the integrative approach of Eastern thinking, one that transcends the boundaries of Western philosophy.

All Is "We," Linked by Karma

In understanding Seo Do-ho's integrative approach, one major theme we need to grasp is the concept of karma. Karma is also the name of mammoth 2010 stainless steel sculpture, measuring 365 cm, showing people clutching one another to form one continuous shape. This motif of people joining into one giant whole is not an unfamiliar one to Seo -- we also find it in previous works like Some/One (2001) or Cause and Effect (2007). From the Eastern standpoint of the Mahayana self, the individual that goes by the name of "I" is made up of innumerable others. This leads us to the conclusion that countless "yous" are present inside of one "me." That is karma. The "I" that exists at this moment did not form in isolation, but was built on the supporting foundation of others.

Seo Do-ho_Paratrooper V_linen, polyester, concrete, plastic, mixed media_2005

In a 2003 work, Seo shows us the dress-shoed footfalls of a gentleman moving in rapid strides. Beneath them are many other people, all racing along with him. This work, too, is titled Karma. A superficial viewing might suggest some enormous, superior being trampling the weak and vulnerable, but what interests Seo Do-ho is the countless others that enable each of us to move along. The self can only walk when supported by many different people; it can only survive through its relationships with them. Moreover, it expresses the sophisticated humility of one who exalts "us" by lowering "me," and who, in so doing, further elevates the self. The virtue of humility was studied extensively by Korea's Confucian scholars. A similar theme, that of the self being the point where karmic ties to innumerable others come together, can be found in Paratrooper V. There, the tiny soldier pulls on a parachute many hundreds of times bigger than his own body. At the end of it are the embroidered names of three thousand people -- the people tied to the him, directly and indirectly, by the bonds of karmic affinity. As his size suggests, he is in fact the tiny and typical "petit bourgeois." From time to time, even the most ordinary of people is a node in the great universe.

Seo Do-ho_ Cause and Effect_stainless, steel, Aluminum, mixed media_2007

"There came a moment," Seo says, "when I realized I truly was made up of all these facts, all these people and relationships." The recurring presence in his work of objects that serve to connect and relate things and spaces -- handles, hinges, bridges, corridors, stairways -- can be traced to the artist's beliefs about karma. The reason it has met with such a profound response from global audiences is because it shows this Mahayana concept, the acceptance of others as a part of oneself, at a particularly painful time in history, one where national divisions are fostered and selfishness reigns in the name of the globalization of capital. For the more than two decades since 1991, Seo Do-ho has been a nomad traveling the world, and the message he speaks is this: in spite of differences of nation, race, or religion, each of us here and now is someone precious, bound to everyone else by the ties of karma.

The Nomadic Self Grows

Whether he is in Seoul, New York, Berlin, or London, and whatever he happens to encounter, it is all Seo's karma, a part of his life, and his self, like a plant, grows in limitless profusion. Conflicts do arise from time to time as he encounters new cultures in a new environment, but in Seo Do-ho's work those conflicts result in converge and symbiosis, not conflict or defeat. The Korean Hanok home enters within the Western structure to become a "home within home," and recovers its perfectly serene transparency in the process. A more recent work is Seoul House/Seoul House, in which the artist's the main house in Seoul finally makes an appearance. More than a decade in the making, this old new work dominates the gallery with its majesty. Originating from a house of fabric, it has a sarangchae (a type of guesthouse characteristic of the traditional Korean home) fashioned out of cloth, modeled on the palace hall of Yeongyeong-dang. The boy who grown up in the sarangchae is now the man of the house. The newly solid self moves beyond passively fumbling within memory for the place he was cast into, and begins actively shaping his world.

The first series that shows the world wrought by Seo is the Perfect House-Bridge Project. This nomad has returned repeatedly to the question of what makes the "perfect house." Traveling back and forth, over and over again, between Seoul and New York, he found himself thinking how nice it would be to build a home in the middle. This project is the result of it. It starts from the crazy notion of building a home at the halfway point -- in the Pacific Ocean. The house is located on water, so building a bridge to connect the two cities was more important than a house. Seo says that he is working out the details with a biologist, architect, and science fiction writers. Is this notion -- a bridge in the Pacific -- too fantastical? Not at all. If one has the flexibility of thought to convert an immobile home into mobile property, and if contemplation naturally extends into the immaterial world rather than remaining bound in the material, then who's to say anything in art is impossible? No more is Seo Do-ho a shooting star from the East landing in the West.

This year, Seo plans to do a project on the Hamyeong-jeon, a room in Deoksu Palace that once served as the bedroom of Gojong, the last Joseon emperor. He also plans to do a site-specific work for the Gwangju Biennale, one that incorporates the properties of the host city. One can sense the focus of his interest shifting from private memory to collective history. When next we see Seo Do-ho, it will not be as a nomad moving about within the world given to him, but as a nomadic architect who actively interprets history and crafts a world of his own.

[Photo courtesy of Kim Atta]

Lee Jin-sook / Art Critic

Lee received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Seoul National University’s Department of German Language & Literature. She received another master’s degree dealing with Kazimir Malevich at the Russian State University for the Humanities’ Division of History of Art. She runs the programs “Between Russian Art and Literature” and “A Thematic History of Western Art” and teaches at Dongduk Women’s University, Yonsei University, and Chung-Ang University. She regularly contributes to columns such as “Lee Jin-sook and Artists of Our Era” (Monthly Top Class) and “Lee Jin-sook’s In-depth Reading of Art Books” (Joongang SUNDAY). She is the author of the Russian Art History (Minumin, 2007), an introduction to Russian painters, The Big Bang of Art (Minumsa, 2010), a criticism on young Korean artists, and a collection of art essays called Depending on Beauty.