In the work of Hong Kyung-taek, we find all sorts of oppositions: glorious color and monochrome, pattems (abstract) and profane, classical orchestra and funk, closeure and eruption, high end mass cult, painting and design. The titles of solo exhibition Shrine, Funkestra, Purgatorium, and so forth are themselves outpourings, in their turn, of the confliciting elements harbored within the artist. "From religion to pomography, I want to paint a picture of our times vivid, raw, and unvamished," says Hong, and theme that runs through his whole oeuvre.

- \!\[Kim Atta\]\(http://theartro\.kr/eng/focus/20120726/hkt/interpro\.gif\)

- \*\*Hong Kyung\-taek/ artist\*\* A professional painter since graduating with a degree in painting from Kyungwon University in 1994\, Hong has long been trying to narrow the gap between art and the public through his exhibitions\. This has included Shrine\, Insa Art Space\, Seoul \(2000\)\, Flow: New Tendencies in Korean Narrative Painting \(2001\)\, an Arco Gallery invitational exhibition\, Funkchestra: Opposing Translation \(2005\)\, an exhibition celebrating the 15th anniversary of normalized relations between Korea and China \(2007\)\, a Korean contemporary art tour in Central and Latin America called Peppermint Candy\, a contemporary Korean art exhibition in Russia \(2008\)\, A Different Similarity: Towards the Sea \(2009\)\, which introduced Korean art to Russia and Germany\, a Doosan Gallery New York artist\-in\-residence and solo exhibition \(2010\)\, Fashion into Art\, a collaboration with fashion designers \(2011\)\, and an exhibition with the Gwangju Museum of Art in commemoration of its 20th anniversary \(2012\)

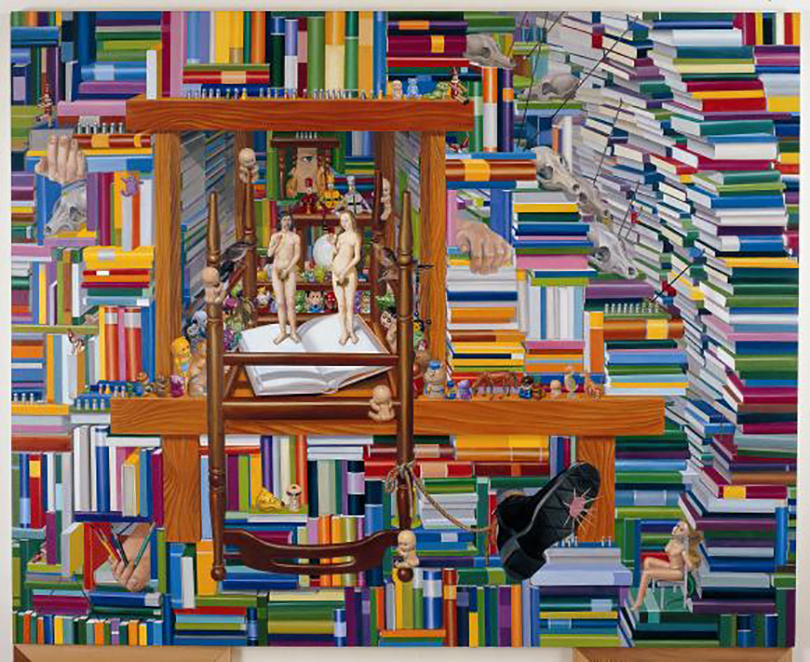

The Library : A Space for the Hermit in Seclusion

Hong's The Library series is a modern twist on the bookshelf painting Chaekgado ,a common theme in traditional Korean folk art. Once, these pictures adorned the rooms of Joseon Dynasty -era Confucian scholars, symbolizing the values that dominated their lives. Forever keeping his books near, the scholar had as his greatest virtues the practices of introspection and cultivation. The primary significance of the Chaekgado was to represent the scholar's space, where he contented himself with poverty and followed the Way, refusing any compromise with a corrupt world. Over time, a number of other meanings became attached -- the style was enriched by elements like beautiful ceramics, or fruits and flowers that symbolized the vicissitudes of life.

Hong Kyung-taek_ Library 5_oil on canvas_130x162cm_2005

As a 21st century version of the Chaekgado Hong's The Library paintings show us the space of a hermit, where a war with the world's wickedness is being waged in the name of the individual. As was the case with the old Chaekgado Hong's libraries are not just for books. What volumes sit on the shelves -- philosophy, cartoons, or erotica -- is not important. Rather, it is the cumulativeness of form that matters. These books have shed all the color and texture that denote classical heft and grandeur, acquiring instead a gaudy, fluorescent plastic sheen. They are bricks, shutting out all intrusions from the outside and forming an enclosed space, and they are decorative elements that fill the canvas. (This accords precisely with the patterns in the Funkestra series.) The densely packed canvases -- one critic spoke of a "fear of the vacuum" -- also express Hong's sensibilities as a designer.

In some works, his questioning of the world's corruption draws directly on images like Hugo van der Goes' Adam and Eve, Botticelli's Venus, or the Madonna -- or from toys, their faces childlike, dumped in a trash can. Coupled with the insular spaces, these images evoke an even louder emotional response. Some of the pieces show cacti against the backdrop of the densely packed bookshelves. In the chaekgado paintings of old, it was orchids that symbolized the lofty aspirations of the scholar; here, it is a plant whose leaves have been transformed into thorns. The artist notes the closed form of the cactus, and the twofold insularity -- that of the plant with a space already sealed off with books -- creates a density that borders on the suffocating. In no way is this space open to the outside. As though recalling the depth of the unconscious, the space merely leads, mazelike, into a deeper space. The more closed off the physical space of the painting is, the deeper the layers of psychological space expressed within it.

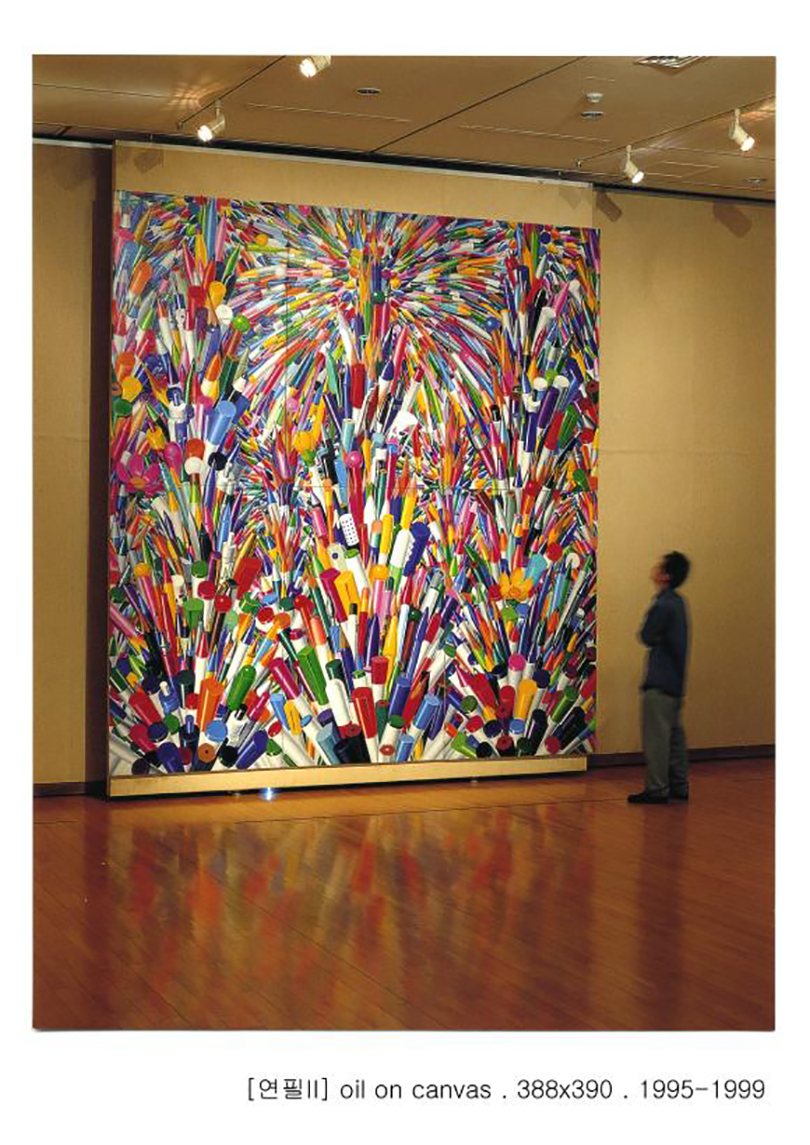

A Pencil Eruption

Outside The Library, this place bricked up by fluorescent books, the world is dominated by overt expressions of brutality. Inspired by children's toys, the Insect Collection series centers on rudimentary metal robots. Their weapons are pencils and other sharp objects typically used by children. These paintings are the work of a man who was once a thoughtful young boy who felt shock and pity at the sight of other children cruelly and thoughtlessly killing insects with pencils. Hong exposes the moments when everyday things become weapons of murder -- the fickle brutality inherent to life.

Hong Kyung-taek_ PencilⅡ_oil on canvas_388x390cm_1995-1999

Funkestra 1 : Feeling the Color in Music

The word "funkestra" is a portmanteau combining "funk" -- a style of music that is bold, provocative and direct, boasting effervescent rhythms and sensuality -- and "orchestra," a concept linked to the genre of classical music. It is a good description for the artistic world of Hong Kyung-taek. The funkestra world is one where dazzling color meets monochrome, patterns (abstraction) meets realism, sacred meets profane, closuremeets eruption, high end meets mass cult, painting meets design, religion meets porn. In Hong's work, music carries crucial importance. It fills The Library of his hermits. And with Funkestra, we see someone with the rare skill of "colored hearing" -- like Kandinsky, Hong senses the color in sound. Music floats through the air, before arriving, one day, to settle within his painting. Lines are broken; everything fragments into color points. The Funkestra world marks an end to grand narrative and the beginning of a pursuit of hedonistic sensuality.

Combining the driving beat of funk with the explicit, brazen colors of the plastic culture that surrounds us, the patterns here carry visual pleasure to a heightened extreme. Filling every last corner of the canvas is a chain of sound, one that carries not only the main rhythm and melodies of the music, but exhilarating grooves that exist solely to add to the pleasure. These are small, incidental sounds that go unheard in open spaces, but they come through loud and clear when you adopt the insular approach of the hermit sporting earphones. Just as all kinds of sound come together to form musical content, so meaningless colors are connected (patterned) according to a splendid formal logic to form a painting. Hong gives his canvas the electrifying feeling of funk music with an orchestral harmony of dazzling color. This is also an exercise of Hong's outstanding sense for design. For a long time, Korean painting was dominated by monochrome, abstract canvases in solid colors. Through Hong, it breaks away from this rule. He is the supreme colorist in Korean art, achieving visual pleasure in the true sense.

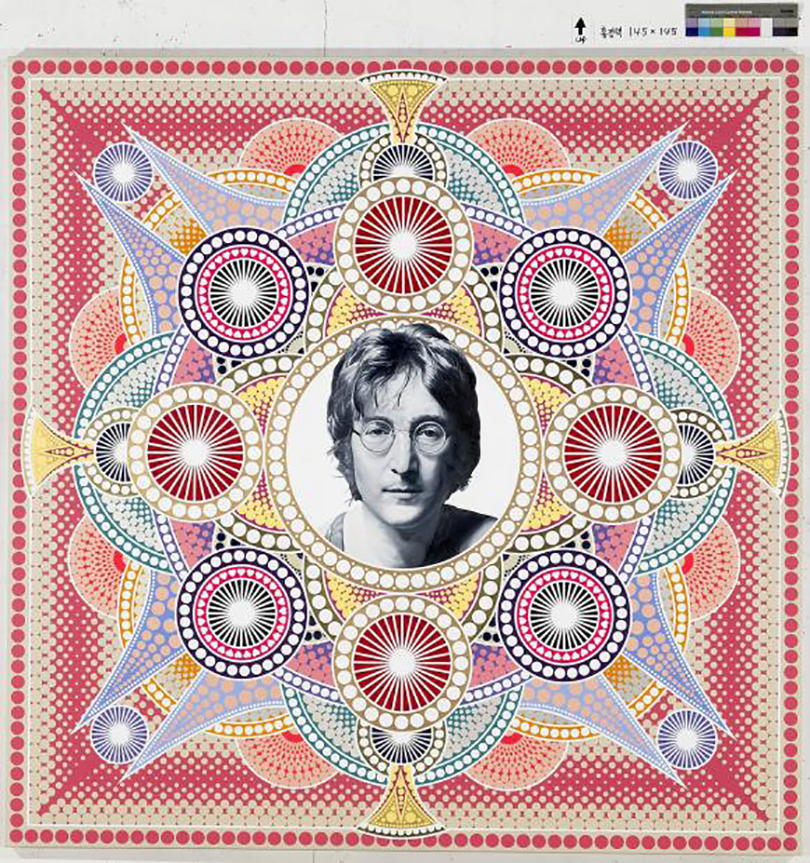

Funkestra 2 : An Era's Icons Take the Stage

While this clamorous music is ringing out the Funkestra canvas, icons and messages also appear in multiple layers. They take center stage without distinctions of sacred and profane, becoming the Funkestra performers playing under the artist's conducting. The first of them include Pope John Paul II, the singer Prince, director Park Chan-wook, media artist Nam June Paik, actress Ha Ji-won, the Beatles, Andy Warhol, Kate Moss, and Vincent Van Gogh. Behind them, light emanates from the center like the halo that lit the heads of saints in medieval art. These are the cultural icons of our age, collected in Hong Kyung-taek's scrapbook.

Hong Kyung-taek_Jonh Lenon_acrylic & oil on canvas_145x145cm_2007

Popular culture icons first began intruding upon the highbrow culture of fine art in the 1960s, with the pop art genre. In his use of brilliant plastic colors and mass cult imagery, Hong writes a crucial new chapter in the history of Korean pop art. Some of the figures appearing at the center of the canvas are rendered in black and white -- here, Hong is referencing how he first saw them. The monochrome image of John Lennon, nose long and glasses round, is a relic from a bygone era when it was in wide distribution. Sometimes, the pictures are flat like theater placards.

The Funkestra stage also houses a line from a popular song. This genre is lyric poetry for an era when lyric poetry is silent. The famous philosophical proposition "I think, therefore I am" transforms here into the pop lyric "I rock, therefore I am." The meaning of life, the mode of living -- everything has changed. And ways of receiving the text are changing as well: the text is now a visually polished image, one that is scanned, instantaneously and in toto, to become embedded on the brain of its viewer. Foreign lyrics, with their mixture of code and slang, are not always understood clearly by Korean listeners, a fact that only brings to the visual pleasure aspect into sharper relief. The ability to give a text this kind of visual directness is a testament to Hong's supreme design sense.

Funkestra 3 : Music in Purgatory

Of course, it isn't just popular music that fills his canvas; there is also a more sacred kind. These works, with their vertical patterns like the sound displays on old-fashioned equalizers, have a different sort of background music from the pieces described above. Gone are the varying grooves that might burst out unexpectedly at any moment; the style here seems far more orderly, solemn. This series is based on the idea of the triptych, a traditional style of religious painting, and the works in it can be opened up horizontally. As in the old religious art with their images of saints, the main image in the center lines up with additional images on either side.

Hong's Funkestra is eternally in the present tense, capable of accommodating an inexhaustible range of icons. "I'm searching," he says, "for this kind of petty contemporaneity." In capturing the non-great contemporariness of a non-great era, Funkestra is a means of collecting images of our era for what might be called a museum project. In Purgatorium, it is the artist himself who is captured in this device. Appearing in the guise of a martyr, he represents an intermediate being who links the real world with a greater one from a place that midway of purgatory, between hell and paradiss. That being possesses both a longing for heaven and memories of hell. Hong's Funkestra performs in neither of these, but in purgatory.

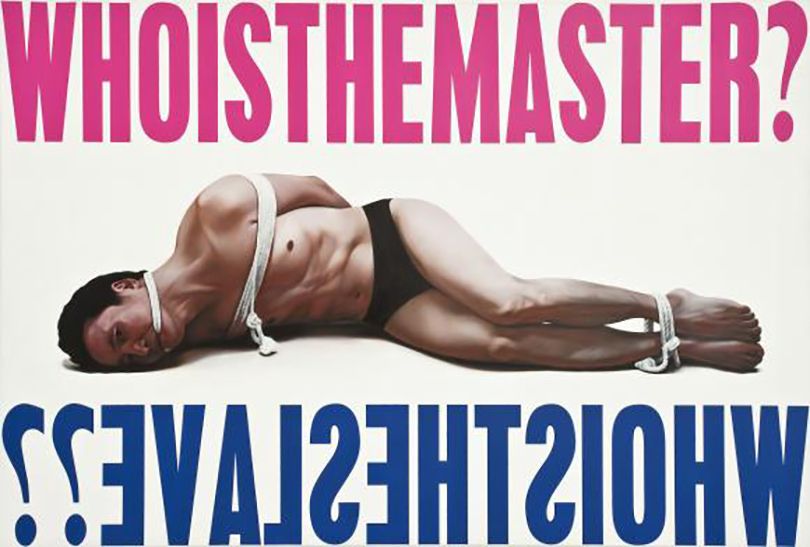

Hong Kyung-taek_Master&Slave_acrylic & oil on linen_130x193.5cm_2010

There is a new form of violence that confronts the Funkestra performers: the market. Hong has enjoyed extraordinary popularity in the art market, but he poses a question here to those who respect him for purely commercial reasons. "Who is the master?" asks the person in bondage, and that person is Hong Kyung-taek himself. In its mixture of realism and thick, inflammatory Gothic type, this work calls to mind the traditional poster; the extended crosswise shape suggests Hans Holbein the Younger's Body of the Dead Christ. In his recent work, Hong has made frequent use of skull and butterfly motifs -- the traditional imagery of the vanitas. The revival of this genre is being spurred on by a present-day environment where trumpets noisily proclaim the global victory of capitalism, and the goods that inundate us are bewitching enough to change a person's very mind. In an artistic world where the power of money grows stronger with each day, the bound and gagged artist asks us, "Just who is the master?" It is a question coming from a man of piercing insights into an era.

[Photo courtesy of Hong Kyung-taek]

Lee Jin-sook / Art Critic

Lee received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Seoul National University’s Department of German Language & Literature. She received another master’s degree dealing with Kazimir Malevich at the Russian State University for the Humanities’ Division of History of Art. She runs the programs “Between Russian Art and Literature” and “A Thematic History of Western Art” and teaches at Dongduk Women’s University, Yonsei University, and Chung-Ang University. She regularly contributes to columns such as “Lee Jin-sook and Artists of Our Era” (Monthly Top Class) and “Lee Jin-sook’s In-depth Reading of Art Books” (Joongang SUNDAY). She is the author of the Russian Art History (Minumin, 2007), an introduction to Russian painters, The Big Bang of Art (Minumsa, 2010), a criticism on young Korean artists, and a collection of art essays called Depending on Beauty.