Kim Hong Joo's paintings bloom on canvases like flowers. When asked why he paints flowers, his answer is simple: "because flowers," one whose name we cannot know. When he painted one recent lawn, it was so flat it almost became abstract, an image without a specific sense of space or direction.

- **Kim Hong\-joo/ artist** Born in Hoin, Chungcheongbuk-do in 1945\, Kim graduated from Hongik University’s Department of Occidental Painting and attended graduate school at the same university\. Starting with his first solo exhibition in 1978\, he has held 15 solo exhibitions and been part of many group exhibitions\. He is the recipient of the Frontier Award at the Grand Prix Exhibition of Korean Art \(1978\)\, the Special Award at the Cagne International Painting Festival\, France \(1980\)\, and the 6th Lee In\-sung Artist Award \(2005\)\.

The Rhetoric of Stammering, the Silence of Eloquence

"The flower blooms on the mountain

The flower blooms, spring, and summer

The flower blooms

On the mountain

On the mountain

The blossoming flower blooms all alone

Little bird, crying on the mountain

Loving the flower

Lives on the mountain

On the mountain, the flower now falls

The flower falls

Fall, spring, and summer

The flower falls"

In a monotonous yet lucid cadence, the poet Kim So-wol sings again and again of the flower blooming and falling. In this repetition, he observed time in the universe; thus flows the time of a flower's blooming and falling, and the time of nature. Viewed as a whole, the movement of nature seems to repeat in a cycle; viewed up close, nothing is exactly like anything else. This is the providence and mystery of nature. In its repetition of simple phrases, Kim's short poem sings of the boundless providence of the universe. It is the rhetoric of stammering, the silence of eloquence.

Kim So-wol's flower bloomed on the mountain; Kim Hong-joo's blooms on the canvas. At first glance, the great flowers that fill the frame seem to be floating outside of gravity. The frail petals are in full bloom and layered over top of one another. Drawn before the image by the petals, the viewer comes under a magic spell: the flowers disappear, and the traces of countless brushstrokes, interlinked like capillaries, transform into a road that flows along its way. A once-traveled mountain path, a stream of water flowing away and leaving us behind -- all become flowers that unfold before our eyes. But if you look for the name of the flowers that seem enveloped in layers of mystery, you will find all of them marked "Untitled." Insist on searching for them, and you may see lotuses, chrysanthemums, dahlias, strawberries, paulownia leaves, and squash. The reason Kim insists on leaving his work untitled is because he is not painting a concrete portrait of the flowers.

Kim Hong-joo_Untitled_acrylic on canvas_146x143cm_2009

Kim Hong-joo_Untitled/(detail)_acrylic on canvas_96.5x96.5cm_2009

The Korean word for nature is Jayeon. Literally, this means "being just as it is." Kim's paintings, too, blossom on the canvas like flowers in bloom. When asked, "Why flowers?" his answer is simple: because they are there. And, indeed, a look at his recent work shows that is no longer "the flower" -- identifiable -- but simply "a flower," its name unknowable. His lawns are so flat as to verge on the abstract, lacking any concrete sense of space or direction. Though it seems to unfold carelessly, Kim's canvas is packed with presence. From far away, we see the shapes of the flowers, and the countless repetitions of brushstrokes; from up close, we see that none of them is repeated or identical. Such is the providence of Kim Hong-joo's art. In a series of works, he has shaped a two-layered world through the doubling of images. Like Kim So-wol's poem, his paintings show the rhetoric of stammering and the silence of eloquence.

Kim Hong-joo Is Kim Hong-joo

Kim Hong-joo is Kim Hong-joo. Born in 1945, he cannot be sorted into any specific school of art. He belongs to himself. His work has operated in ten-year cycles, their differences as natural as nature itself. In changing, he has followed the currents of Korean art history, but he has never taken the path most travelled. His history has been one of asking and solving the most painterly of questions about Korean painting and the history of the art. In the 1970s, he began working with the S.T Group, a collective of conceptual artists who represented the most iconoclastic trend of their day. They emerged as a reaction against the Monochrome Paintings that was then dominating the country's artistic world. But Kim was not suited to working under fixed concepts and goals. He became more and more certain that painting should be done with the hand, not the head. A painting, he began to believe, was done by hand. A painting was the act of painting itself.

Following this brief flirtation with conceptual art, he returned to painting in the mid-1970s. His work consisted of realistic portraits in mirrors and wooden window frames. It was a time when many painters were doing hyperrealistic work, capturing objects on the canvas in elaborate detail. But Kim made the bold move of bringing objects into the painting. He would produce an elaborate portrait of someone with the solemn bearing of a high priest, and then hang a stringy thread beard on it. Comical at first glance, this work questions the very "realism" of hyperrealism. If you want reality, you have reality. Why does painting need to be just like it?

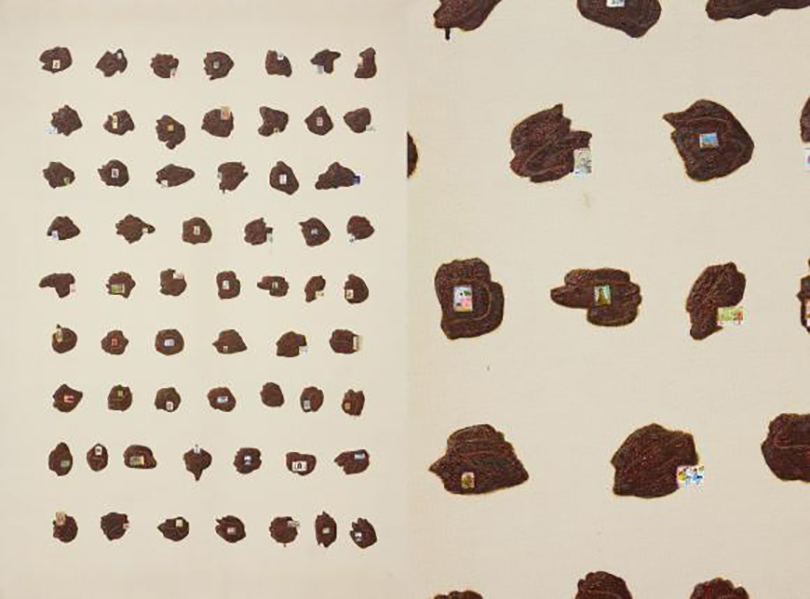

Kim Hong-joo_Untitled/(detail)_acrylic on canvas with objects_216.5x148.5cm_1993

It is significant that Kim chose mirrors and window frames as his objects. At the time, there was a work by Ko Young-hoon called This Is a Stone, which was a kind of declaration of Korean hyperrealism. Ko's picture was a reversal of Rene Magritte's The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe), which was itself a reaction/manifesto against representation theory. This Is a Stone proclaimed the truth of the represented image and the legitimacy of realism. Representation theory described painting as a "window to reflect the world," and artists of this day were tacitly situated inside the window. As alluded to in Magritte's 1933 word La Condition Humaine, it was a structure where an artist inside the window painted the world seen outside it.

But Kim's self-portrait on an old wooden door has him looking outside the window from within. We find a dramatic reversal: until that point, the viewer saw the world as observed and recreated by the artist. Its objectivity was made possible by the painter's reliance on the visual framework of perspective. Only that way could the painting becoming something true, something that represented the world properly. But Kim's 1979 self-portrait (Untitled) shows the artist staring outside the window. The viewer see not just Kim Hong-joo, but the very situation of the artist. Reality may be limitless, but we find ourselves asking whether the artist can actually see the truth by looking at the world from inside the window. The portrait above the mirror calls to mind, in the most straightforward of ways, the pictorial concept of the "mirror reflecting the world." A broken mirror shows only a distorted, kaleidoscopic image; a dusty mirror cannot reflect the world accurately. Kim Hong-joo paints in the pigments of Western art, but he does not follow Western notions of painting.

Maybe, Maybe Not

Above all else, Kim Hong-joo has been a painter, an ontological designation that has been every beginning and every end for him. As someone who paints pictures, he naturally found himself questioning the idea of painting. In the late 1980s, he came out with detailed works that appeared from afar to be sinuous cursive Chinese calligraphy, but on closer inspection turned out to be feces. Kim recalls his childhood, when the parlor and living room in his traditional Korean home were "surrounded by scrolls and screens with indecipherable script on them, which I was cautioned not to touch lest they be damaged." Since he had no way of knowing what they meant, the Chinese characters were just an image to him. Things with occult significance actively intrude on reality through the invocation of prayers and taboo. This view of the image was something patently different from Western-style art premised on a disconnect between art and reality. This is not to say that Kim followed the Eastern art perspective of script and painting being one. He opted for a third route. In this work, where what appears to be a Chinese character from afar turns out to be excrement when viewed up close, we find the world of Kim Hong-joo, where everything comes down to the image.

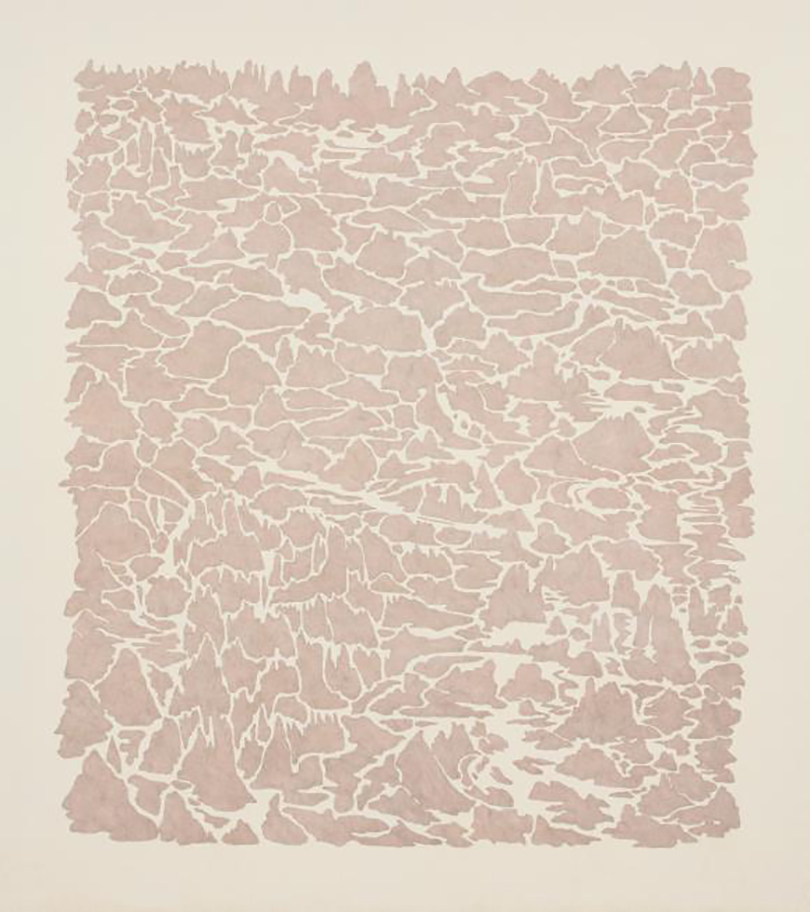

Around the same time, Kim painted landscapes with a dual image: mountains and fields when viewed up close, an inverted man's face when seen from farther away. This doubling, however, presumes the free movement of someone who sees the whole through the parts, and then the parts through the whole. Indeed, the second image is only captured when one walks backward away from the canvas. In Western art, there is a strict division between painting that represents reality and symbols that encode it. No matter how precisely a map corresponds to the actual world, it is not a representation of reality. In Kim's world, however, not only Chinese characters but the symbols used on maps are incorporated into the universe of pictorial image. The world of Muwei Jayeon, (unacted upon nature) includes not only flowers but small thickets and nameless bugs; the painter brings all of these into the world of images. The only ticket granting admission is the painter's act in painting it.

Begun in the late 1990s, the flower paintings are an extension of this work. The dual images whose separation had sustained the tension in the landscape and excrement paintings are now joined together in these works, becoming both more covert and more sophisticated. Kim works with an thin Oriental painting brush, just a few strands thick. The delicate strokes leave the canvas with a sense of the artist's hand walking slowly over it. And as the softness of the brush meets the lucid primary colors of Western-style acrylic paints, the result is a greater beauty on the canvas. This is how Kim's fantastic flowers were born. Kim does decide an overall shape before painting, but he has no way of knowing what the finished product will be as he paints the equivalent of a hand's span a day. He feels out the path of these tactile brushstrokes, the product of tireless labor, and in the process he comes across another world. "As I paint the tiny veins of the petals," he says, "there comes a moment when I realize that what I'm painting may not be a flower at all, but a road, or a river, or a mountain." Under close observation, the overall form of a flower suddenly dissipates into thin and delicate brush lines.

Kim Hong-joo_Untitled_acrylic on canvas_162x162cm_2002

Echoes of Unacted-Upon Nature

Kim Hong-joo did not set out to become something, or to paint anything in particular. He just painted. He lost himself in the act of painting. The thin, endlessly repeated brush lines are the traces that this absorption leaves behind on the canvas. Seeing this immersion in painting and the traces of the many strokes, the critic Kim Won-bang said Kim Hong-joo had "come up with a new way of rejecting representation." For his neutralization of representational art, the critic gave the painter the ironic handle of "enemy of painting." It would be more accurate, however, to say that Kim Hong-joo is an opponent of Western painting, and its emphasis on representation. He is the creator of a new style of painting, where by varying his perspective he has been able to develop something characteristically Korean.

Choi Soon-woo devoted his life to exploring Korean beauty. In describing it, he used a complex mixture of modifiers -- for the nature of Korean beauty is a subtlely that cannot be expressed through any one word. "Bright, yet deep and quiet in its serenity"; "Soft and gentle, and also frail"; "seemingly chaotic, yet simply; seemingly simple, yet calm" -- it is through clusters like this, bouquets of language, that Choi described old Korean art. It would not be going too far to apply them also to the work of Kim Hong-joo, who shapes a two-layered world that seems to unfold carelessly, yet is suffused with presence. Choi also said that Korean art, which puts nature and art on the same plane, appeared to have "neither any reckoning of painting something in particular, nor, if you really look at it, anything really wanting." It arrived, he added, at a "beauty of inattention that transcends technique." As its greatest virtue, he pointed to its "unaffected naturalness": harmonizing with nature, yet even this harmony is not deliberately sought.

Kim Hong-joo_Untitled_acrylic on canvas_225x200cm_2007

We also find this virtue in the painter himself. "I don't paint with the result in mind," he says. "I paint because I enjoy it, and it ends up becoming something. It's up to the viewer to sense what it is. It's natural for me to paint, like putting on clothes when it's cold and taking them off when it's hot. I'm not painting to produce any effect. It's the same no matter what I'm painting." This attitude is deeply rooted in Korean aesthetics. As someone born in 1945, he may well remember the old Korean sentiments from before modernization. Choi said that Korean art views nature and art as being on the same plane. By this, he meant that it focuses not only on the paramount virtue of harmony with nature, but also the process leading up to it. What Korean art shows is the act of not consciously pursuing that harmony, let alone a finished product -- a process of "naturalness without artifice." The creative process here is not mystified along Western lines, but constitutes a repetition, like human labor as a part of nature. It connotes a process in which creation takes place slowly, as a day-to-day routine, changing all the while, with all manner of peripheral elements incorporated as a matter of course. The many brushstrokes Kim Hong-joo leaves on his canvas are a collection of this labor. And what makes this collection beautiful is how it resembles the concept of nature as "being just as it is." It is in this sense that Kim's painting represents a modernization of the supreme virtues of Korean painting.

Lee Jin-sook / Art Critic

Lee received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Seoul National University’s Department of German Language & Literature. She received another master’s degree dealing with Kazimir Malevich at the Russian State University for the Humanities’ Division of History of Art. She runs the programs “Between Russian Art and Literature” and “A Thematic History of Western Art” and teaches at Dongduk Women’s University, Yonsei University, and Chung-Ang University. She regularly contributes to columns such as “Lee Jin-sook and Artists of Our Era” (Monthly Top Class) and “Lee Jin-sook’s In-depth Reading of Art Books” (Joongang SUNDAY). She is the author of the Russian Art History (Minumin, 2007), an introduction to Russian painters, The Big Bang of Art (Minumsa, 2010), a criticism on young Korean artists, and a collection of art essays called Depending on Beauty.