From moment to moment in our daily lives, we play the role of mediator between ourselves, objects, and our surroundings. For the most part, we reflect on what surrounds us according to agreed-upon rules. Surviving on the stage of the real world requires real tenacity and strength. Things that are too stiff and straight are vulnerable to breaking in an instant; the idea of shaping ourselves in the right ways while retaining the elasticity of rubber evokes the image of a kind of real-world “Frankenstein,” one capable of looking fondly on the cynical gaze. Actively introduced into lives at the center of error and negation, our body becomes an object of contemplation, and we are able to confront the resulting errors themselves. The central framework of the novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1817) and the 1931 film adaptation Frankenstein is a story about material civilization and a resulting tragedy, themes through which it is fascinating to consider the recent work of Jungyoon Hyen, which focuses on the gaze directed at the “monster” created by the scientist Dr. Frankenstein. The bizarre “monster” created by novelist Mary Shelley (1797–1851) is a repudiated entity. While it exists beyond the bounds of humanity, it also represents the legitimation of those who have the “potential to be repudiated,” as well as the resulting state of repudiation. Prometheus, the figure from Greek mythology whose name appears in the novel’s subtitle, plays the role of creator in his original narrative, having created humanity out of earth, but he is also punished for giving fire to humanity by having his liver repeatedly torn out by an eagle. The mythical narrative symbolically illustrates the clashing and subversion of humanity within the perceptions of civilization. Strange bodies and “wrong” beings, depicted here through terror and alienation, resemble latent societal attitudes toward sculptures of the body that have been an ongoing element in Hyen’s work. In various sculptural ways, she represents the violation of boundaries in the contexts of the body and our surrounding environment while also focusing on her own hybrid being as she transforms basic technology and raw forms into something bizarre.

Walking on tiptoes, 2018, exhibition view, Korean Cultural Centre UK. Courtesy of the artist

see you from here, 2018, Jesmonite, Jesmonite pigment, plywood, steel, acrylic paint, 36x50x39cm x 2. Courtesy of the artist

Looking back at Hyen’s earliest work, we can see how she has focused on spatial rules and order, using transformed and derived ideas to create cracks in the overlooked relationships of attachment between her objects’ existence and their settings. Her attention is directed at the state of an object “occupying” its surroundings as it radiates a sense of existence, transporting relationships of attachment into bizarre bodies—an approach that dates back to her work History of Bowlegs(2014). While imagining urban spaces with pre-written rules, Hyen cast in cement four vertical shapes to represent the process of a legs becoming bowed, aiming to encourage viewers to imagine the relationships between objects and the body. Each a shape cast from the widening, silhouetted space between the bowed legs, the sculptures are speakers unto themselves. But in her various subsequent installations—beginning with the exhibition Walking on tiptoes (2018, Korean Cultural Centre UK, London)—Hyen has presented a theatrical form of sculptural narratives to contemplate each situation surrounding her work. An example of this can be found in I see you from here (2018), where a form that presents the physical act of walking on tiptoe speaks to the relationship between the body and a space, leading viewers to imagine that the floor upon which they tread may not be so firm. The situations posited in Hyen’s sculptures originate in scenarios where the presence of an object can be determined while the work is made to stand independently as its own speaker, focusing on the peripheral byproducts (such as in These will be the days, 2018) and evidence rather than concretely visualizing the unseen presence. The temporal sense of peripherality that accompanies Hyen’s works presents itself somewhat stubbornly in sculptural form as the invisible situations surrounding the objects are realized through the artist’s trademark cheerful, tragicomic scenarios. Strategic, boundary-blurring devices bear the artist’s attempts to separate her bodies from other bodies outside of the space, or from the means in which movements are represented. The legitimacy of presence is ensured through new motions and situations that are subtly layered upon the object.

Resembling parts removed from a body, Hyen’s sculptures evoke flesh with their coloration, a mixture of skin-colored pigments and Jesmonite, silicone, and plaster. The artist’s color blending and painting play an important conceptual role beyond the physical expression of body parts as the colors decorate the surface in a painterly way, applied over stainless steel pipes that have been forcibly transformed. While the artist used a sleek painting approach from Mama never told me how my dreams will be shattered (2017) to On my knees (2019), her sculptural identity has recently become blurred with the pronounced chiaroscuro elements in With All My Heart (2021). Also while the works in her “dislocated body” series through 2019 (On my way 1, 2, 2019) are bizarre sculptures of bodies as subjective presences, Hyen has increasingly neutralized visual subjectivity through the adoption of disparate physical devices, as if “silencing” her objects. Individually, her sculptures occupy space, but since Hyen incorporates binding and silencing into the works themselves, they become things that cannot exist freely. On the whole, linear items such as locks, chains, and latex are used as frames to surround and control the sculpted masses, and the subtle relationship of tension that results fetishistically depicts a non-productive dialectic between subject and object, material and form. Hyen’s “abusive” attitude toward sculpture—in which she consciously tries to control and confine her objects through cold and sharpened mechanisms—is meant to capture the precarious moments of a mass’s expansion and compression as its physical qualities are transformed. Creating a momentary form actually entails a long and difficult weaving process, one accompanied by the exhilaration of the “sadistic” execution of the artist’s sculptural practice. The gestures that Hyen adheres to in her repetitive production process converge upon a consistent attitude that involves feelings like fear, trepidation, escape, avoidance, and loathing. Her hands follow the outline of her chosen shape, alternating between the direction she desires and the direction she does not as she works the object with her fingertips. As she establishes her role, she grasps the sense of physical weight and reflects on the mass’s structure.

Breathing beside you, 2020, wire mesh, plastic cup, epoxy resin, pendant, fake plant, steel, resin, chain, fabric, clay, polystyrene foam glue, straw, urethane, gum, dimension variable. Courtesy of the artist.

YOUNG KOREAN ARTIST 2021, exhibition view, MMCA. Courtesy of the artist

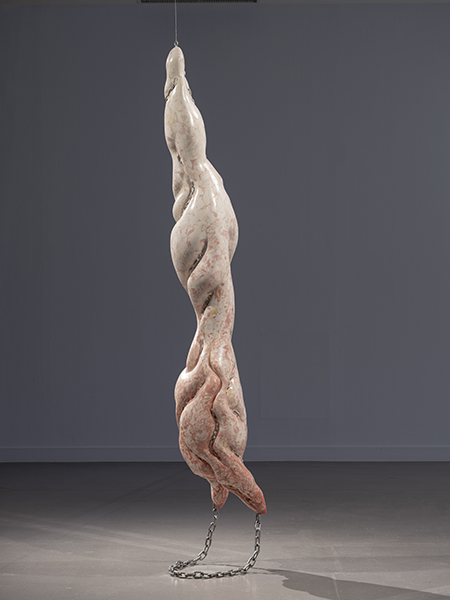

In Breathing beside you(2020), the artist captures a “grin and bear it” mentality as well as an inability to fully mourn a disaster when one is focused on one’s own survival. Using two approaches, she explores the clear “stage” structure of a dystopia with no escape, providing a chilling glimpse at an artificial stage where rickety supports hold up the sculpture as a whole. Her recent work, in contrast, focuses on a more realistic form of sculptural practice—one that borders on the negation of the body, desire, and the self. Among her pieces from 2021 in particular, a number prominently feature their own forms of roleplay in which the artist’s focus appears to be less on the objects that she is attempting to understand and more on a particular area of interest. With her interest in objects as obstacles increasing, Hyen has developed a method that involves combining a physical state with a physical space through acrobatic movement. The individual sculptures made using this method occupy space independently, but Hyen sustains their individual tension by accentuating the arbitrariness of acts. In her recent efforts to craft vague and bizarre full-body, reclining, seated, and bust forms, the artist has created a matrix that represents the body through the use of fluid materials. Indeed, these works find references for sculptural shapes in people standing on their head (Comfy State, 2021), using a hula hoop (The Hula Hoop Queen, 2021), wrapping their bodies tightly in shoelaces to restrain one’s movement (With All My Heart, 2021), kneeling or standing with one’s arms folded (Mid-Boss, 2021), and pole dancing (Never Let You Go, 2021). Introducing object devices into physical actions, Hyen focuses on the fetishistic approach of restraining the object to suit the device’s structure and shape. Her disparate mixtures of chemically soft and pliable masses of Jesmonite, resin, and Styrofoam with cold and sharp materials such as PVC piping, pipe clamps, chains, and stainless steel result in hysterical settings as the sculptures become subtly mixed and fixed in place with the concept of objects.

Comfy state, 2021, chain, polystyrene foam, resin, pigment, 270x42x46 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The way in which Hyen pierces her sculptures to imagine the layered structure behind them or their inner parts is much like delving into the viscera behind a lump of meat. The resin sculpture work Comfy State communicates a sense of blood rising to someone’s head during a long handstand through its mixture of colors and the shaping of the clay. The physical characteristics expressed by the flesh-colored resin are quite different from the previous ways in which the artist granted feminine properties to viscous parts of the body to show resistance against phallic forms of visual language. The humor deployed by Hyen as she occupies, controls, and gives away her sculptures turns her approach into one of individual “stand-up comedy,” creating an orderly theatrical stage through the arbitrariness of sculpture and the ways in which she delves into the cracks that emerge as a sculpture approaches completion. Dispersed across space, her sculptures exist according to a “non-place” stance, each of them forming a stage unto itself. This calls to mind the way in which Rosalind E. Krauss (b. 1941) described sculpture existing as a “negative condition”—Hyen seems to arrive at affirmation through the negation of negation and with something that is not even a body. Alternating between dislocation and junction, the sculptures simultaneously negate the bidirectionality of body and object, allowing for a result that satisfies this condition to exist through the affirmation of a complex whole. The artist assigns anonymous characters to physical sculptures stripped of place, summoning the codes of materiality from the realm of reverie to create an enigmatic state. Her attitude of attempting to capture errors rather than the desiring gaze inflicted on the body repudiates her belief in the body as an organic whole.

Hyen also introduces prosthesis to her sculptures, encouraging viewers to focus on primal forms that defy eugenic being and emphasizing human deficiency and vulnerability. In doing so, she makes viewers witness the either real or fictional results. With the uncanny forms and properties conveyed by the sculptures’ hybrid exteriors, she redistributes difference and identity, focusing on the comical products of social reality within the patterns of resonance and interference that exist in the works’ interstices. The inverted relationship between mass and structure is repeatedly woven, shaped, and revised by the artist’s hand, creating forms that blur the definition of what is responsible for the distortions. These forms evoke a schismatic system in which desire is produced, alongside a feeling of black comedy. With her dynamic reactions to objects, the artist seeks moments of curious equilibrium that arise from collapse and control in her sculptures. The enormous works, precariously sustained by their reference points, create acrobatic scenes as they shore one another up. In this way, Hyen organizes her sculptures within the scope of her hand’s reach, as though seizing and understanding a small world within the “one-person stage” she has developed and reflecting upon some paradoxical aspect where it becomes impossible use the stage to achieve a realization. Each product that emerges from the artist’s hands bears a connection to her efforts to observe herself, and this aspect brings to mind the image of a different body mediating the sculpture as well as the sculptural practice of alternate molding and weaving, as the artist feels, shapes, and pares away her objects. A common element of her works is the way they elicit a dialectical combination of the relationship between the human body and the foreign or “other” materials with which it is merged. This element is the “living dead,” lurking offstage before emerging at the end of the show just before the curtain call. And behind that curtain is Hyen, an observer who disrupts subjectivity as she materializes the joy of subtly controlling her objects. We can imagine her precariously confronting her own concealed and disparate “other” while existing as a figure in a repeated show on a stage that continuously divides in bizarre ways.

※ This content was first published in 『2021 MMCA Goyang Residency Program Catalogue』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Goyang.

Sungah Serena Choo

Sungah Serena Choo is a self-driven and dedicated contemporary art curator and writer with 7+ years of experience specialized in identifying and examining the connections and differences between the latest trends of the emerging Korean artists scene. Prior to becoming an independent curator, freelance writer, and a co-founder of BGA (mobile/web art subscription platform), she gained her unique and dynamic point of view from her past curatorial career experiences such as Juree Kim Solo Exhibition 0 Columns(TINC), FOLDED-UNFOLDED(Sungkok Art Museum), The Prequel(Platform-L), COLD PITCH(BB&M), PRIME MONUMENT(N/A), Bek Hyunjin: Public Hiding(Royal X), The 8th Amado Award Shadowland(Amado Art Space), The Snark: Suddenly Vanishing Away(Gallery 2), Hyejin Jo Solo Exhibition Shape, From the Side: Reading Documents(d/p), Things: Sculptural Practice(Doosan Gallery), Hee Joon Lee Solo Exhibition_ Interior nor Exterior: Prototype_(Kigoja) etc. She also worked as an assistant curator at a major public museum SeMA and Asian Art Center before her independent career. The hybrid projects she has been organizing in recent years which combine both philanthropic and commercial aspects demonstrate the opposite, proving that art is perceived as the ultimate symbol of knowledge and culture.