Feral in Seoul series, 2021, preserved plant materials, single-channel video, dimensions variable. Photo by Yeonkeun Choi. Image provided by MMCA.

Soyo Lee’s Feral in Seoul series opens up our senses towards the city. The project suggests that we refresh our spatial awareness of assuming the city as a location exclusive to humans. It also redirects our attention to non-human agents around us—entities who haven’t yet entered or system of awareness despite of always sharing time and space with us. Such sentiment is in line with that of ‘urban political ecology,’ a recent addition to academic epistemology and methodology of looking at our urban living space with new modes of attention.

Urban political ecology, as the name suggests, is an attempt to look at ecology from a political stance. Environmental sociology and environmental geography are also equivalent terms used in nearby academic disciplines that share a common epistemological foundation—which is the social construction of nature. This means such methods presume there are inseparable relationships between politics and ecology, and environment and society, conducting analysis by linking issues in these areas all together. In other words, ecological issues are interpreted as political relationships, and environmental issues are explained within our society. Then why the particular emphasis of ‘urban’ political ecology in the nomenclature? Urban political ecology strategically emphasizes the ‘urban’ conditions in political ecology (Heynen et al., 2006). Such attempt is a type of metaphor for critically refreshing research methods and issues of space in conventional political ecology. This perspective criticizes how conventional political ecology has been reinforcing the separation between politics and ecology by seeing ‘nature’ as something belonging to the ‘third world’, or ‘wilderness’ far away in isolation. The emphasis on ‘urban’ in the terminology is to remind us that urban environment is also a part of ‘nature.’ How has political ecology transformed with the addition of ‘urban?’ Is it merely an intellectual self reflection among the peers of political ecologists? I would like to assert that there are definitely more to this attempt. ‘Urban’ as a strategic term, allows us to defamiliarize conventional spaces which we have utterly taken for granted (Amin & Thrift, 2017). In particular, the term has caused a groundbreaking transition to the subjects, periods and methods of political ecology. Urban nature is a concept devised to expand spatial epistemology of the urban space as a human settlement, and contribute a spatio- spatiotemporal explanation of relationalities among animals, plants, objects, infrastructures and humans within the city. Therefore, urban nature is not just an interest in ‘nature within the city,’ but more fundamentally, it is an attempt to deconstruct binary boundaries between human and non-human, artifact and nature, and rural and urban, the conventional concepts dividing up our urban space (Ernstson & Sörlin, 2019). In this respect, Feral in Seoul has the common perspective with urban political ecology as considering urban life as a part of nature—or urban nature so to speak—and goes on to inspire the field by expanding its research subjects and methods.

Feral in Seoul – Yago(野菰), Mushroom in a Sense, 2021, preserved plant materials, single-channel video, dimensions variable. Photo by Yeonkeun Choi. Image provided by MMCA.

Feral in Seoul – Yago(野菰), Mushroom in a Sense, 2021, detail. Image provided by MMCA.

Through examples of plant species setting in the niches of city spaces, Soyo Lee attends to Seoul as a place of historicity and materiality of urban development experienced by the Korean society. In particular, the materiality of the plantae which has been making place for itself within multifarious artifacts built by humans, illuminates the essence of diverse ‘urbanness’ as we perceive. The artist also reveals the performativity of the nation-state, which assumes the ‘imagery of nature we long for’ through develop mentalistic state projects such as urban renewal and reforestation. We humans have always been able to plan what we want, make these designs operate, and also take pride in the success of these performances. On the other hand, non-humans find their own niches within this controlled environment. They reveal unique materialities and performativities, sometimes adapting to and in other times resisting and disturbing manmade plans. They create emergent ecologies which are unexpected and innumerable to humans (Kirksey, 2015).

Feral in Seoul – Paulownia tomentosa, 2021, detail. Image provided by MMCA.

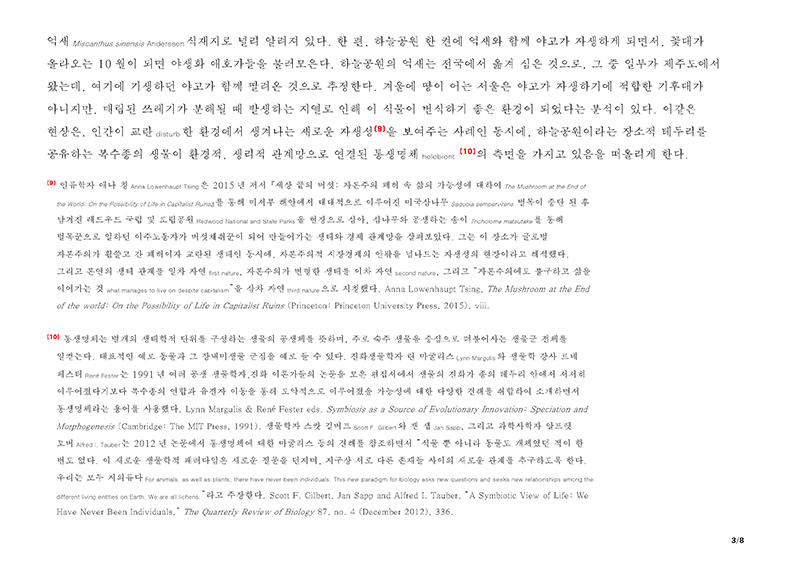

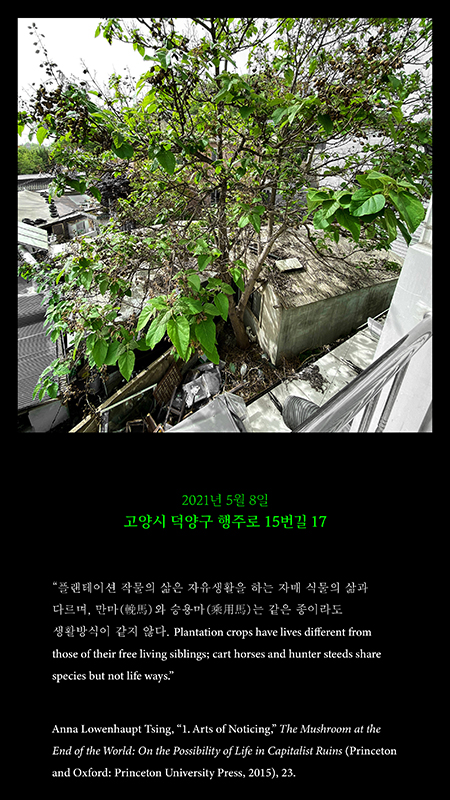

Feral in Seoul shows aspects of political ecology in two ways. First, to arouse methodological opinion, the artist herself can be seen as an urban political ecologist. Soyo Lee reveals the diversity of non-human agents who are imperceptibly assembled within urban spaces. An empress tree (Paulownia tomentosa) sprouts under water dripping from an outdoor AC unit. Another one practically merges with a cement wall throughout the time of more than twenty years, without anyone really noticing it. There is also the indian broomrape (Aeginetia indica), a plant that’s “like mushrooms.” This parasitic plant thrives at a silvergrass garden at Haneul Park, built on top of an exhausted landfill that releases geothermal heat. The non-human agents exposed through Soyo’s projects reconstruct our sense of time and space simply by paying more attention to their ways of existence. Secondly, Feral in Seoul brings up the problem of scale. The appearances of non-human agents observed by the artist are often imperceptible to the naked eyes of humans. Soyo re-scales these existences by fabricating them into artistic objects. This process of discourse making further allows us to discover new historicity within these non-human agents.

Another important aspect of Soyo Lee’s practices is active fieldwork. She captures diverse non-human agents, and actively approaches them to reveal their lives. She speculates upon their characteristics by verifying their modes of being at the actual habitats—whether they be the mountains or cities nationwide. The entire process of collecting, breeding, preserving the discovered organisms to develop discourses can be considered as an art piece in and of itself. A biological species to speak for itself within the hands of the artist takes at least a full year of time and labor. During this time, Soyo pre-inspects the life cycle of her non-human agents, surveys when, where and how to encounter them, and sets off into the field. Such intimacy to the field can be seen as a unique form of artistic practice for understanding the complexity of relations between humans and non-humans.

Note to 『Illustrations of Joseon Plants: A Selection of Toxic Plants』, 2021, installation of preserved plant materials and documents. Photo by Yeonkeun Choi. Image provided by MMCA.

Note to 『Illustrations of Joseon Plants: A Selection of Toxic Plants』, 2021, detail. Photo by Yeonkeun Choi. Image provided by MMCA.

Feral in Seoul allows us to rethink the meaning of ‘feral’, a word nonexistent in the Korean language and has been translated liberally as ‘rewilding’ or ‘revival.’ We humans have always believed we have shaped and transformed nature according to our plans and intents—however, Soyo Lee’s works introduce cracks in this faith. The life cycle and materialistic characters of nonhuman nature does not always act upon the intents of humans. Those who have gone “feral in Seoul” here had not been released by humans nor had been released independently. What has happened was that a unique relationship between human and non-human has formed though particular material, social, political, historical and cultural encounters. Humans had not made the outdoor AC unit to drip water for the empress tree seed to settle. One of the countless seeds spreading all over the city had just coincidentally met this water to germinate. Indian broomrape at Haneul Park were parasitic to silvergrass transplanted from Jeju-do, an island 455 kilometers south of Seoul. Indian broomrapes are subtropical plants and cannot survive in frozen earth. However, they were able to continue their multispecies relationship at Haneul Park thanks to the geothermal heat from the former landfill underneath the park. As in these cases, the relationship between human and non-human entities is emergent as well as unexpected. The human and non-human relationality is never determined in a specific direction. It never happens as we intend. Therefore, this particular relationality cannot be interpreted as romanticized nature and restoration narrative, nor can it be seen as simple violence, conquest, and natural resource narratives by human to nature. Soyo Lee reaches beyond such binary narratives and presents complex multispecies relations and their topographies. The scenes of urban nature displayed by the artist proposes a novel way of illustrating nature by challenging the binaries of human and non-human, artificial and natural, and rural and urban.

Note to 『Illustrations of Joseon Plants: A Selection of Toxic Plants』, 2021, work process. Image provided by MMCA.

[Bibliography]

1) Amin, Ash & Thrift, Proff. Seeing like a city. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. 2017.

2) Ernstson, Henrik., Sörlin Sverker. Grounding urban natures: histories and futures of urban ecologies. Massachusetts: MIT Press. 2019.

3) Heynen, Nick., Kaika, Maria., & Swyngedouw, Erik. (Eds.). In the nature of cities: urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism. New York: Taylor & Francis. 2006.

4) Kirksey, Eben. Emergent ecologies. North Carolina: Duke University Press. 2015.

※ This content was first published in 『2021 MMCA Changdong Residency Program Catalogue』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Changdong Residency.

Junsoo Kim

Junsoo Kim completed his undergraduate and master's degree in sociology at Yonsei University and completed his doctorate at KAIST's Graduate School of Science and Technology Policy. Various studies have been conducted on the relationship between the state and nature, and in particular, several papers on geography beyond humans and the anthropology of East Asia have been published. He studied how non-human actors created the form, ability, and performance of modern countries, and studied urban pigeons, the Han River, African swine fever, and exotic red crayfish. Recently, non-human actors mobilized during the imperialist period and foreign species of fish that have been transferred from East Asia to North America are being studied on how national ecological knowledge is being produced.