Island for Fisherman, 2021, buoy presumed to have floated out of the Exclusive Economic Zone of Korea and China, copper, dimensions variable. Image provided by MMCA.

Most human beings and sculptures are beings/things that stand upright on the ground. Sculptures (and sculptors) have repeated a process of entrusting things to the ground, entangling with it and providing resistance against it. The artwork of Chung Soyoung considers the ground, space, and place as an essential background and prerequisite for sculpture (both the artwork and the process) in geological, social, and political terms, materializing multiple layers of history and concepts. In other words, her work can be seen as questioning art (sculpture) as something that boils down to substance and image, while exploring the physical time and space of the “here and now” in which we are situated with its numerous mixtures and layers of species and boundaries.

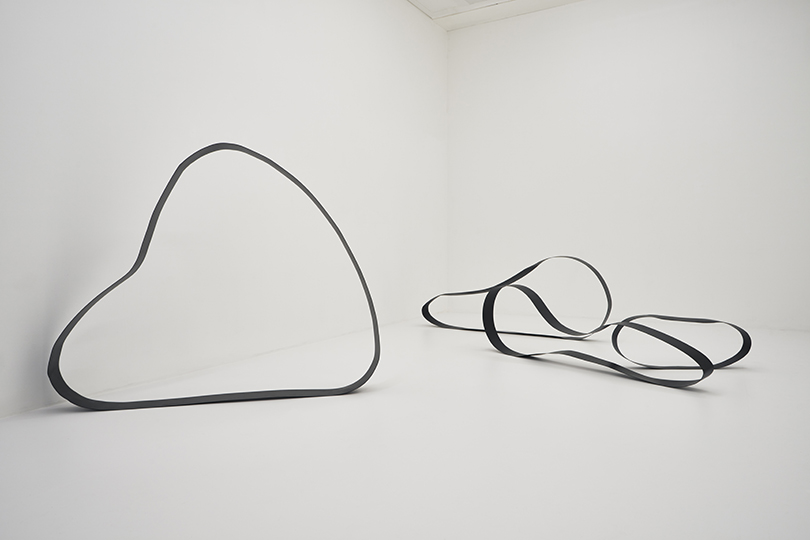

In addition to both being connected with the ground as a physical space, sculpture and geology share another commonality in the way they activate the “before” and “after” of time as it accretes. To begin with, sculpture often ends up as a mass, regardless of whatever the process or attempt was. It is for this reason that traditional sculpture so often represented absolute and unchanging values as objects of veneration. Geology typically analyzes and applies the composition and structure of the earth’s surface as predetermined data. Sculpture is the creation of countless movements of the hands; the earth’s surface is a collection of various properties and structures. Both break down and reproduce their absoluteness through the past. Chung focuses on this deconstruction and reproduction of time, instantiating sculpture not as some fixed and unchanging outcome but as a form of change and tempo. Focusing more on the activation of “prior” and “posterior” space and time than the absoluteness of a predetermined substance, she presents sculpture as a form of modernity and as a medium of growth and direction. The tempo of sculpture here is the polar opposite of discrete, indiscriminately arising incidents of mental derangement; it comes across as the continuous rhythm of the world—small-scale yet vast. Chung’s sculptures are formed through movements that are superfluous yet unceasing, unraveling themselves as they permeate the deeper layers of the world. In this sense, their uprightness comes across not as that of the past hammered into the ground, but as a kind of pilgrimage or roaming journey. As a backdrop for this, the exhibition setting and the ground become spaces that evoke history, emotion, and memories beyond existing boundaries.

Rolling, 2020-2021, steel and powder coating, dimensions variable. Image provided by MMCA.

Indeed, Chung’s artwork breaks down exclusionary ideas through a fairly direct form of “walking” or “roaming.” Stone (2016) and Horizon (2016) are video records of a kind of performance originating in particular perceptions of the DMZ as a place. Through actions that move and shift between weight and lightness, brightness and darkness, vertical and horizontal, they express a superficially present boundary by means of an intensely physical and psychological space. A few of the works in Chung’s Tectonic Memories series (2017–) use the surface of the earth in cities visited by the artist as a starting point for recalling movements that permeate and transcend various social and political strata, including the boundaries of geopolitical territories. Jet Lag (2021), which was featured in Chung’s recent solo exhibition Sea Cucumber, Manganese and Ear (2021)—which once again shifted and expanded the artist’s interest in “earth” into the realm of the sea—includes two revolving structures that viewers are able to push and move on their own. Situated at odd angles to one another, they guide viewers into an unsynchronized world. Other works include Drawing an Island_ (2020), which repeatedly shows the movement of a boat sketching a thin line over the open sea; Island for Fisherman (2021), which was created with a buoy that drifted in to the Korean coast from the waters of Korea and China’s exclusive economic zones; and Mirrors for Mirok Li (2021–), inspired by the life of Mirok Li, author of The Yalu Flows (1946) who went into exile in Germany to evade arrest by imperial Japan after taking part in Korea’s March 1st Independence Movement. These words pass through various movements and tempos, their afterimages becoming layered on top of each other as the resulting sculpture is presented as a medium for achieving an unknown space and time.

Jet Lag, 2021, steel pipe, mesh, bearing, fish net, powder coating, LED light and plywood, 160 × 270 × 300 cm. Image provided by MMCA.

Mirror for Mirok Li, 2021, silver mirror reaction on glass, stainless steel, (each) 80 × 120 × 6 cm. Image provided by MMCA.

Like sculpture, human beings also stand upright on the earth. How do they appear in Chung’s work? As explained before, works like ISA (International Seabed Authority)(2021), Tectonic Memories Chapter V. Words (2020), and Tectonic Memories Chapter I. A Romance (2017) involve activities by the (human) artist that create states in which animate beings and inanimate things, the material and non-material, and yesterday and today coexist and connect. This in turn ties in with an assemblage of infinities and non-boundaries. Along the same lines, the human being (human experience), which we may suggest is the starting point for the work, can be said to represent not some special being that surpasses the world, but just another biological or geological species that coexists with other living things, species, and substances. The concept of species coexisting symbiotically with other beings can be related to the distinction between life as bíos and life as zoé, which has been made by philosophers from Aristotle to Giorgio Agamben. In Chung’s work, the human being is not so much bíos—a systematically established, socially defined way of existing like ethnicity, culture, and gender—as it is zoé, a way of being that is shared by all organisms. In other words, the activities of humans appear not as those of the oft-mentioned Homo-genus of sociocultural beings, but as those of beings equal in value to their neighboring organisms. Here, one might imagine the invalidation of universal and rational thought. While Chung does not present any clear-cut declarations or critiques, humans in her work equate themselves with the world as understood in terms of the “outside” and “other”—expanding and reconfiguring the scope of thought as a matter of course. This can be detected more clearly when the “London clay” reaches the river that bisects the city and overlaps with the exteriors of buildings in the cityscape, or when it overlaps once again with the grid of a window inside a house. It can also be experienced in Mirrors for Mirok Li, where viewers encounter images/afterimages that are not perfectly controlled, alternating between projection and reflection as the body moves from place to place.

As they push the structures in the gallery and wander among the mirrors and glass, images and afterimages, viewers finally assimilate with the human/species that appears in Chung’s work. Taking part both directly and indirectly in the artist’s movements, shifts, and tempos, viewers are not the absolute subject capable of anything, but more like zoé—organisms on equal terms, geological beings. In the process, they might break away momentarily from the world as diorama, excessively adorned and governed by economies of speed, to rediscover the world as part of oneself, per se, and the micro-scale tempos, times, and relationships associated with it. Seemingly connected with the past and death, with nothing happening within it, Chung’s work produces a gaze and a form of wandering that transcend the limits of consumerist illusion and identity.

Drawing an Island, 2020, single-channel video, sound, 5 min 33 sec(loop). Image provided by MMCA.

So where do these movements of material and image that break their own limits ultimately point? The movements are oriented back toward the ground we stand on, and toward the core of an unknown world/sea. The surface of the earth surface and ocean and the depths that lie below each of them become spaces that invalidate endings throughout continued, if not easily detectable, dynamism. In her book Manifestly Haraway (2016), Donna Haraway emphasizes the vitality of unseen “chthonic” beings, suggesting that alternative forms of thought can be created by establishing kinship with them. Along the same lines, Chung’s artwork emphasizes the “non-human humans” of the “beyond-human humans” as it forms an assemblage with unfathomable (non-)entities within the earth and sea. The infinite time and space shown by the work’s manganese, mud flats, and glass beaches go beyond the common concept of “post” to elicit activities and imaginings that deconstruct existing models and categories. Chung’s sculptures appear not as fragments and unsustainable separations, but as a dynamis of movement that brings bounded time, history, and human beings into collision and reconnects them.

This interest in spaces that occupy themselves may be a natural one for an artist who deals mainly with matter and who experienced life in different cultures as a child. Pondering the different layers of relationships rather than attempting to artificially manipulate or control things, Chung interrogates the places we occupy not through fixed concepts but through indeterminacy. “How did the here and now come about for me? What have I projected here?” she asks. The geological explorations and imaginations in her work also connect with her clearing away of existing orders and boundaries. “Clearing away” is an artistic form and content here, and its substance is a medium—namely sculpture. The earth and sea that serve as the artist’s subjects and backgrounds invert and transplant the inside and outside of the given symbols and substances, revealing a single whole that facilitates interactions among realms that are conventionally distinguished and prescribed. Contemplating sculpture (and the sculptor) as something on the same level as all life, Chung experiments with an expansiveness and flexibility of art/sculpture/material that does away with boundaries and limitations. In this way, her work appears to raise questions and doubts about the dualistic oppositions of which we so often speak: material and non-material, artificial and natural, and past and future.

Island for Fisherman, 2021, buoy presumed to have floated out of the Exclusive Economic Zone of Korea and China, copper, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

※ This content was first published in 『2021 MMCA Changdong Residency Program Catalogue』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Changdong Residency.

Hyuk-kyu Kwon

Curator