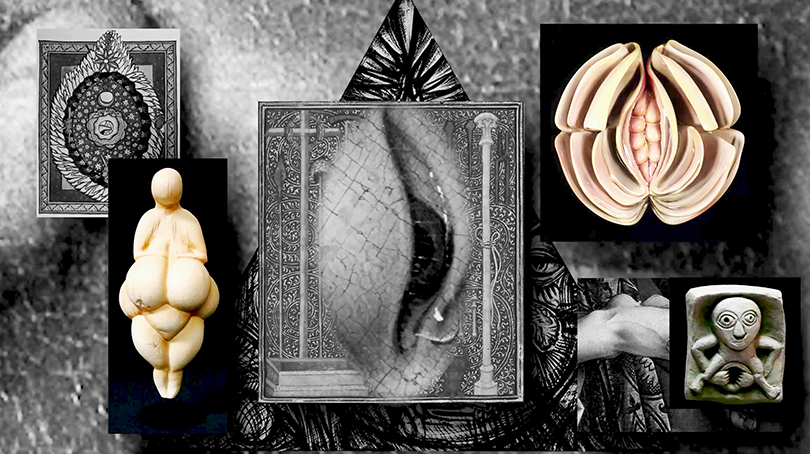

Women/Figure, 2020, Trailer Still Cut, 2min 31sec. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

Here, misogyny’s predecessors and successors gather. From Venus von Willendorf to pornographic memes floating around online, the genealogy of images collected by JANG Pa doesn’t follow the logic of representation. The stale word combinations like corrupt desire or noble worship are even more ineffective in defining her works. They are absorbed into the black hole, thrown from a momentary explosion, wholly eliminated at once, or denied. The images of transgression, those cliché-like images almost close to sexual perversion, which JANG Pa has collected for several years, are themselves stripped naked. And at the same time, they become a place of resurrection in which they are once again stripped from the logic of common sense, the naked.

To pile like Thunder to its close

Then crumble grand away

While everything created hid

This–would be Poetry1)

On the first day of the resurrection, when Magdala Maria recognized Jesus and attempted to touch him, Jesus said “Touch me not.” In this paradoxical moment we are required to think of his words as oxymoron, as “Touch me not” causes contact as in “Take it, this is my body.”2) Excessive images scattered by JANG practically lead to visual desires yet, at the same time, they command a sense of taboo, asking us to look away. The work opens up a space for thinking between the push-pull of desire, what do we have to see? Avoiding generalizing and historicizing, would it be possible to see the images as they are? Can we see nakedness as itself without being stripped naked? Between the will to reach without holding onto a certain meaning and the reflection on one’s recession, how do we reconcile ethics and desire? How can we realize that our will exists outside all of this power?

To see the Summer Sky

Is Poetry, though never in a Book it lie–

True Poem flee–3)

Women/Figure, 2020, Trailer Still Cut, 2min 31sec. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

Everyone has a desire for gaudy pictures in their childhood. Those magazines they peeked at secretly during adolescence as departure from the everyday. The pleasure which arises from such transgression is commonly accompanied by a sense of guilt, which naturally disappears as we grow as a grown-up who can see oneself as the other. However, the continued attachment to this pleasure persists, as does the pursuit of the act of transgression, which leads unknown whether this is driven by a desire for transgression, a fantasy of a fetish, or the magic concealing fear. However, as uselessness and fantasy have long existed at the center of art, JANG Pa prods this space with transgressive images.

A little overflowing word

That any, hearing, had inferred

For Ardor or for Tears,

Though Generations pass away,

Tradition ripen and decay,

As eloquent appears–4)

Installation view of Tangible Error (2020, D/P, Seoul), The Indiscreet Jewels & Women/Figure series, 2020, Acrylic on shaped canvas & mixed media. Image provided by Incheon Art Platform.

Before we are misled with the idea of sociological hatred or hegemonic women, a current trend of thought in Korea, what we need to focus on in JANG’s new series The Indiscreet Jewels (2020) is the genealogy of predecessors maintained through misogyny’s successors. How does this genealogy of misogyny get inherited through history? Who created this genealogy and who required it? Without proper records nor factual basis, filthy jokes have been passed from mouth to mouth, ear to ear, just like magic too widespread or awkward to be categorized in a certain –ism or a trend. Therefore, it is also difficult to account for them within a traditional pedigree. Delivering no lessons at all, they have been branded as tools of hatred which function to protect a sanctuary of civilized men who lead civilization at the expense and targeting of women. Demonization to maintain goodness and witch-craft to protect the high culture have operated without interruption until today. In order to avoid feelings of guilt, those who defend the good and those who create civilization have continuously created objects of hatred as scapegoats. The continued genealogy of Misogyny has been structured not as a social concept but as a social structure.

Witchcraft has not a Pedigree

Tis early as our Breath

And mourners meet it going out

The moment of our death5)

JANG’s journey to find the predecessors of misogyny–a pilgrimage of sorts–is not only her absolute belief in and will for her own worldview, but also, an attempt to confront the conflicting worldviews head-on. Or, as an archeologist dusts off artifacts buried in the ground, her journey may be to strip off the remnants of time from the already stripped naked images of women. JANG’s methodology, collecting images of transgression, chronologically categorizing them, editing them by type, and reorganizing them on the web, does not operate through existing methods of creation, editing, recording, and distribution, nor is it writing a history of betrayal. It frames desire within structures of the romantic, infatuation, and disclosure just as magic operates within its own mechanisms. In this way, we conspire with JANG Pa to embody her personal obsession with images and the pleasure of transgression generated from sanctifying those prohibited images.

[Footnote]

1) Emily DICKINSON, Witchcraft has not a Pedigree, trans. PARK Hyeran (Goyang: Fascicles, 2019), p.37

2) Jean-Luc NANCY, Touch Me Not, trans. LEE Manhyung, CHUNG Gwa-ri (Seoul: Moonji Publishing, 2015), pp.30-32

3) DICKINSON, Op. cit., p.19.

4) Ibid., p.13.

5) DICKINSON, Op. cit., p.5

※ This content was first published in 『2020 Incheon Art Platform Residency Program Catalogue』, and re-published here with the consent of Incheon Art Platform

BAE Euna

BAE Euna is a Seoul-based independent curator. Since 2007, she collaborated in producing contemporary art, writing about her subjective experiences and relationships between individuals created during the process. She was a co-curator of Autodestruccion8: Sinbyeong (Art Sonje Center, Seoul, 2015) by Abraham Cruzvillegas and was invited to Burning Down the House: the 10th Gwangju Biennale(Gwangju, 2014) as a performance collaborative curator. She was an artist-in-residence at Nanji Residency in 2017 as a researcher and operated Ecole Buissonnière and won the exhibition curator competition held by DOOSAN Gallery in 2018 for Cour des Miracle (DOOSAN Gallery Seoul, Seoul). In 2020, she worked for Welcome Back (space ISU, Seoul) as a curator, funded by visual art creation supported by Arts Council Korea.