People / Critic

Sensible Images, Objects that Have Lost Their Function, and the Strategy of a Showroom

posted 17 Oct 2022

There are some objects here—icons of smiley faces or slightly frowny faces, appetizing fruits and bright plants, wall ornaments and patterns that are used to decorate a room to fit one’s taste, and the paint colors that are most popular these days. This scene created by objects is adorned in agreeable images that are adequately refined, satisfy our taste, and connected to the so-called common sensibilities that we frequently encounter everywhere from social media to our actual living environments. Here, “adequate” means suiting popular taste—things that are not too dramatic or maniac, things that are acceptably in line with images frequently accompanied by the hashtags #taste or #sensibility on social media platforms such as Instagram, where the (staged) images of daily life are broadcast live. These popular images form the layers of common sensibility consumed by most people without much disagreement.

〈Breakfast at HOME〉, 2020, acrylic on birch plywood, 180x110cm, 118x78x20cm.

Courtesy of the artist.

When we recall that Pierre Bourdieu, a sociologist who analyzed class tendencies in capitalist society, asserted that a socially established hierarchy of values exists in every cultural product, we can realize that the “taste” of a particular group functions as the index of class. Bourdieu once stated that “taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier” 1) accordingly, agents constructed by the system of social classification are put into situations in which they simultaneously display their own excellence by distinguishing the beautiful from the ugly and define their social position through that excellence (Bourdieu, 6). In line with this, artist Lee Mijung’s work assumes a strategy of using images that easily attract attention in order to touch on issues of taste and class as represented by the familiar and typical tastes of today’s common sensibility. Also, by assertively introducing the endless circulation of images on social media and consumer platforms today, Lee raises questions about contemporary society, in which individuals live without interrogating the images as representations of the artist.

〈Table with a hidden face〉, 2018, acrylic on birch plywood, caster, 70x114x78cm.

Courtesy of the artist.

In many ways, Lee’s works prompt critical thinking about their superficial dimensions, allowing viewers to imagine different possibilities beyond their surface appearance as “tasteful” images. The first is the slippage that occurs at the intersection of the flat image and structural form of an object. The taste or public preference depicted in Lee’s works, such as through the advertisements of a specific brand, smiley or frowny faces resembling emojis, and tones and patterns that recall popular interior design featured in lifestyle magazines or cafés swarming with people—these are the signs that adorn today’s world and narrow down our aesthetics, making them move in one direction toward a single particular trend. In addition, the smoothness of Lee’s superficial images (neatly completed with no unnecessary parts), the calculated thickness of lines, “adequate” arrangement and composition of colors, and rational structures and modular compositions reminiscent of DIY interior design projects remind us of the lifestyles that we have now grown used to, going as far as to stimulate our desire for consumption. However, Lee’s work begins to acquire value when spectators notice that the mode of these objects, which have seemingly assumed the form of furniture, is in fact to maintain a certain distance from the functionality or purpose of the existing products, merely imitating them. This comes from the discord between the images decorating the surface of the object and the purpose of that object. For instance, Lee’s neatly painted images recall the superficialized pictures that are circulated and consumed on digital platforms, reducing the functional structure of furniture to the point of extremity. Viewers’ eyes are thus redirected to the three-dimensional structure of the objects, which, barely managing to stand through the strategic arrangement of angles, do not seem solid enough to serve such a purpose. Spectators then come to realize that the objects standing before them are mere formative props dedicated to the superficial image—irrational objects that have stepped away from the logic of consumption and productivity.

〈Super floor〉, 2018, acrylic on birch plywood, 26x70x70cm.

Courtesy of the artist.

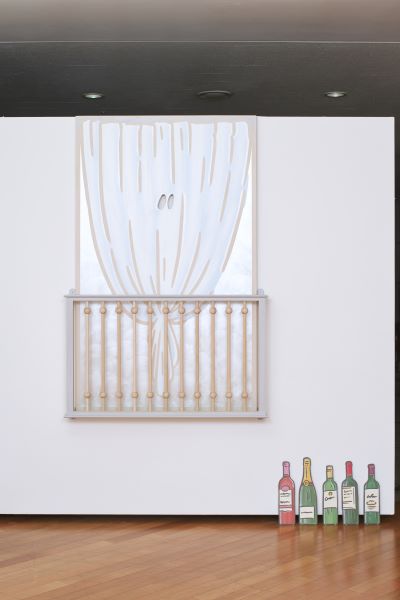

Second, it is worth taking note of the particular images that appear in Lee’s object-form works. On furniture-like objects made of plywood, the artist often adds faces with certain cartoonish expressions. For instance, in Table with a hidden face (2018), a half-circular frowny face painted under the tabletop of a wheeled side table appears to express discomfort about enduring the weight of the objects placed upon it; in Super floor (2018), two holes added to the terrazzo-like floor pattern bring unique emotion to the expressionless, mundane structure. This method is also applied in works such as Green plate series (2018), Flat-pack: plaster series (2018), and Breakfast at HOME (2020), in which Lee adds new vitality to the works by drawing pairs of ellipses on the flat images of green plants or white plaster statues or by turning an image of a sofa covered with white fabric into a cartoonish ghost within the image of a decorative frame. Such anthropomorphism brings life to the dead object-image, and by turning an object into an agent, Lee completely separates the object from a narrative centering on function and use and allows it to enter and expand within a playful narrative unique to the object-image.

Exhibition view of 《The Gold Terrace》(2020, Art delight).

Courtesy of the artist.

Exhibition view of 《SANDWICH TIMES》(2020, SongEun Art cube). Courtesy of the artist.

Courtesy of the artist.

Another interesting aspect of Lee’s work is her display approach and how she constructs the exhibition space. The physical impression of her works, inevitably associated with the images that stimulate people’s common visual sensibilities, stems from Lee’s selection of images that suit a particular taste, which I previously mentioned. However, the physical impression of the works also derives from how they are displayed. For example, on the surface, one of Lee’s past exhibitions, The Gold Terrace (2018, Art Delight), closely resembled a large-scale lifestyle goods store—in other words, a showroom. In the exhibition, a fake vase and fruit display, flat plaster statues, plants, and a side table with a cake placed on it were arranged in “adequate” positions around a flat window containing a golden ray of sunshine in acrylic paint. Together, the objects completed and presented a plausibly unified image. In a different solo exhibition titled SANDWICH TIMES (2020, SongEun ArtCube), Lee employed this display approach in a similar context. Wall system for concentration and Decorative line piece: green plate were installed as a nice pair on one wall, while Decorative line piece: Short curtain, Picturesque (Picture) #01, Delivered flowers #01, #02, #03, _place, and Domino fires, were arranged together in another corner of the exhibition space to create an interior space reminiscent of images in a magazine. Roughly put, putting on an art exhibition is the act of dealing with the operation of a nonlinear narrative. It is like piecing together a fragmented story that has holes in it while strolling through a framework constructed by articulated images lying under the surface of the interaction of the audience and the artwork. Hence, it requires active interpretation to mobilize individuals’ knowledge and experiences, as well as be a forum that presupposes intellectual exchange based on subtext. However, a showroom that presents a meticulously completed environment, defined by the unity of tones and expressions, can be made by arranging objects in their likely places with “adequate” distances between them, taking the shape and color of each object into consideration. In particular, a showroom serves the purpose of proposing, persuading, and encouraging consumption by visually stimulating people’s desires. As such, while showrooms and exhibitions share visuality as their primary sense, they clearly differ in their respective operating mechanisms and goals. What is interesting about Lee’s exhibitions is that by appropriating the appearance of a showroom, she places the spectators on the boundaries of two different characteristics, turning their eyes away from the superficially expressed space or individual objects before them and shaking up their spatial sense and perspective about objects indwelled within them.

Rational modes, attitudes, and trends toward productivity and efficiency, which are closely linked to the logic of capitalism and allow no time for contemplation, suddenly form a primary tendency by being injected into life in the form of a flood of images. Pushed around by them, viewers then lose their agency and end up becoming passive objects that have given themselves to the flow. Instead of responding to these contemporary phenomena with sharp, critical tone, Lee consumes and appropriates today’s modes of life, reduced to superficial images, in a practical dimension. This is to create a time and space to question our lifestyle—the way in which we look at, experience, and understand things in today’s world, where the present is immediately replaced with the past—by actively introducing the circulation and consumption modes of contemporary images into her work. Therefore, the first impression of her work, which acts as bait, and the superficial order of images that surround the surface, entices spectators to wander further away from the exit of the labyrinth. In order to break the double- or triple-locked barriers, one must suspect familiar perspectives and resist accepting things customarily. If you are willing to step onto the stage of intellectual play presented by Lee Mijung, superficial images and forms of imitation will emerge as form of expression that expose the problems of social class and depersonalized modes of life implied in cultural codes.

[Footnote]

1) In Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, while demonstrating that a society’s division of social classes reveals its cultural tastes, Pierre Bourdieu stresses that social agents are bound to reveal their own social positions in the process of making distinctions between the beautiful and the ugly, the distinguished and the vulgar.

※ This content was first published in 『2021 MMCA Goyang Residency Program Catalogue』, and re-published here with the consent of MMCA Goyang.

KIM, Sung woo

KIM Sung woo is a curator and writer, who is interested in ways of producing questions/ questionnaires via curatorial methodologies in contemporary art. KIM directed the curatorial project/ exhibition and management of Amado Art Space, not-for-profit alternative space in Seoul (2015-2019), and was appointed as an artistic director in the form of curatorial collective for the Gwangju Biennale in 2018.

The exhibitions/ projects he has curated include 《Glider》 (Gallery2, 2020), 《Anamorphose : depict but blurry, distant but vivid》 (WESS, 2020), 《Tracing, Detouring, Piercing》 (Hakgojae gallery, 2020), 〈MINUS HOURS》 (Wumin Art Center, 2019), 《Remembrance has a rear and front》 (publishing project, Hejuk Press, 2019), 《The 12th Gwangju Biennale: Imagined Borders》 (Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall, Asia Culture Center, 2018), 《Black Night, Video Night》 (d/p, 2018), 《sunday is monday, monday is Sunday》 (Space Willing n Dealing, 2018), 《Nobody’s Space》 (Amado Art Space, 2016), 《Platform. B》 (Amado Art Space, 2015), and etc.